Mediapart can today reveal the documentary evidence of how a damning report into potentially unlawful protection services provided for Emmanuel Macron's 2017 presidential election campaign was buried by a senior public official.

The 2020 report, carried out by a department within the Ministry of the Interior, referred to “private security services, in all probability carried out in illegal circumstances …. as part of the electoral campaign of the candidate Emmanuel Macron”. In particular, the investigators had unearthed claims of cash payments and of unlicensed security staff working at some campaign events.

Yet despite the recommendation from three senior staff that the matter should lead to administrative punishment measures the case was dropped on the orders of their boss.

The man who shut down the report was senior state official or prefect Cyrille Maillet, who was appointed by the Élysée in 2018 as head of the Conseil National des Activités Privées de Sécurité (CNAPS), a service at the Ministry of the Interior that oversees and regulates the private security sector. He was reappointed in the post in 2021.

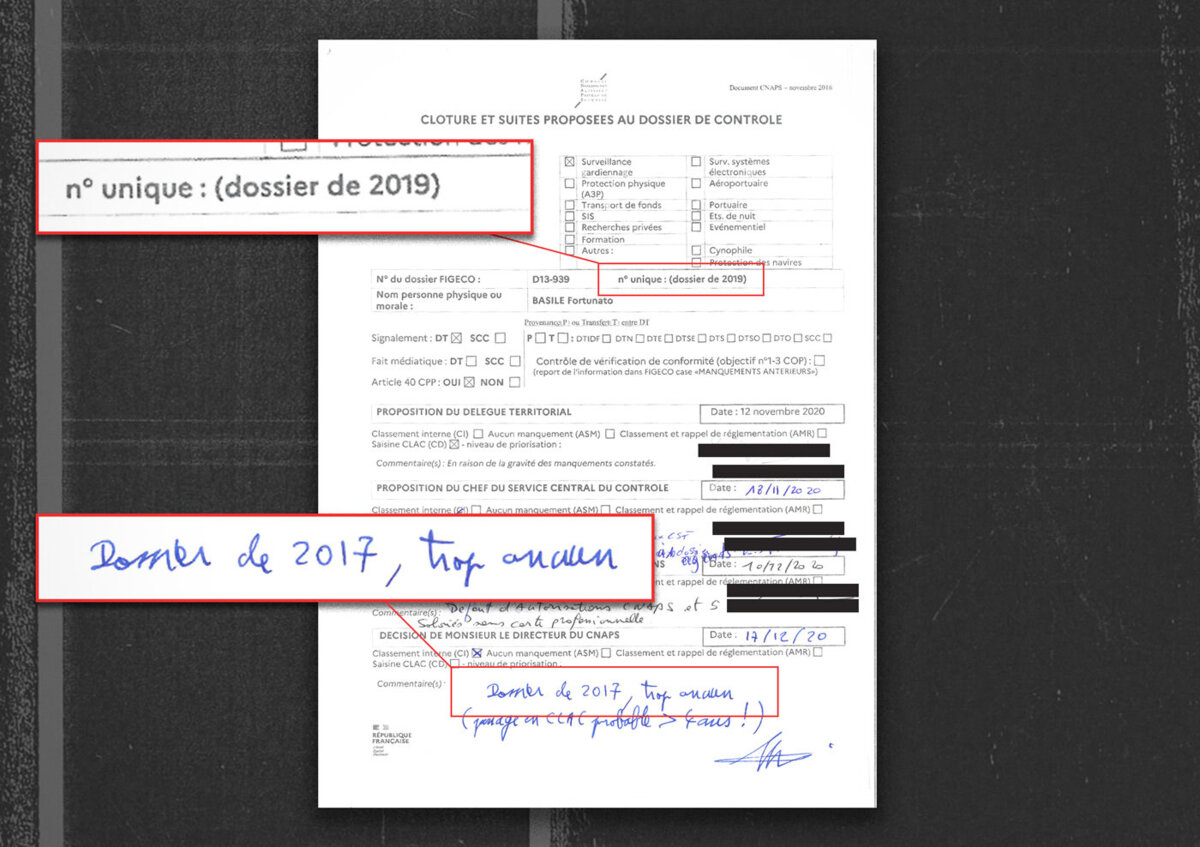

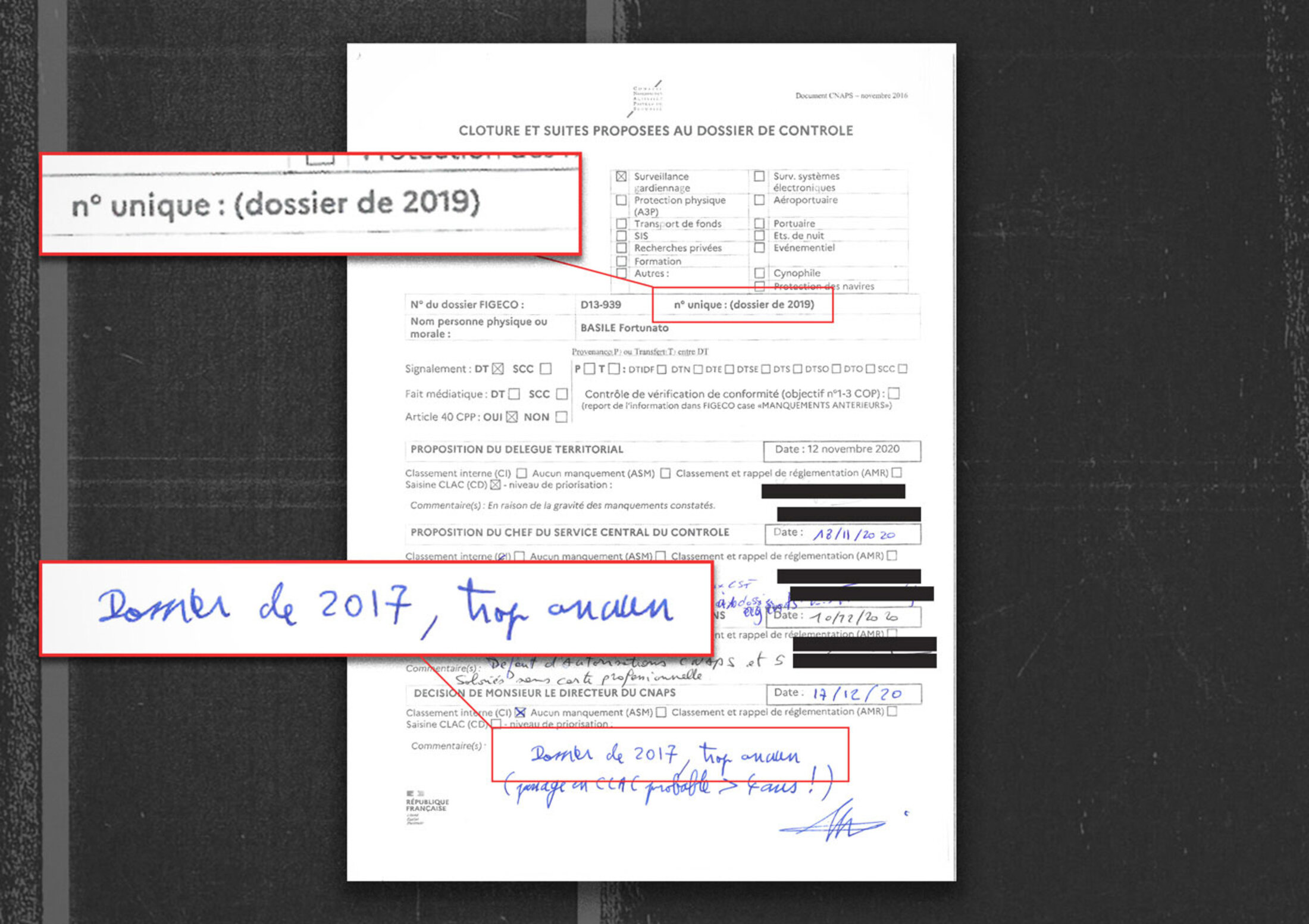

The document that closed down the sensitive investigation, which Mediapart is publishing below, was dated December 17th 2020, and followed a lengthy probe by Maillet's department into the arrangements of a section of the security team in Macron's En Marche! movement during the 2017 campaign.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The investigation had been opened by CNAPS in 2019 after it received evidence from a whistleblower. It unearthed details on the dubious circumstances in which some security staff had been working during the 2017 campaign at the request of Macron's employee Alexandre Benalla, who later worked as the president's personal bodyguard at the Élysée before being sacked in 2018 after videos emerged of him beating up protestors in Paris. Several security operatives gave evidence acknowledging there had been no work contracts and mentioning the use of cash as payment.

In particular, the probe looked at the actions of Fortunato 'Tino' Basile, a prominent figure in the security sector in the south-east of France where the investigation was focused. Basile and Benalla had known each other for many years and worked together, for both Russian and Saudi clients. Fortunato Basile, who denies any wrongdoing, had for example been in charge of security at the Château de la Croë, the Côte d’Azur residence of Russian billionaire and owner of Chelsea football club Roman Abramovich.

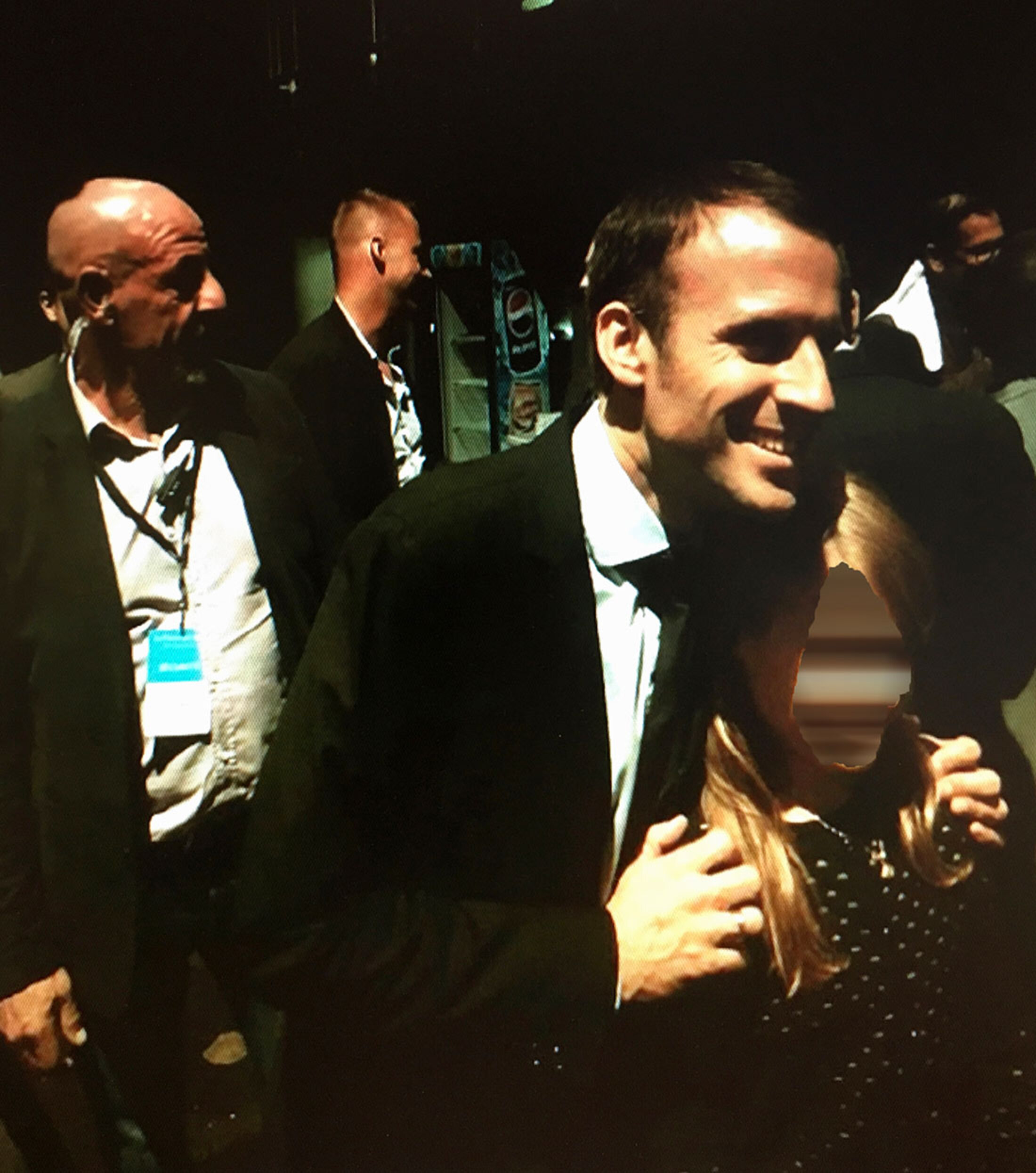

Photographs found in the course of the investigation showed several of the security operatives suspected of having worked illegally for Emmanuel Macron's campaign visiting the Élysée as guests in June 2017 just after the presidential election. In some images Basile can be seen shaking the new president's hand. Other photographs, seen by Mediapart, confirm the presence of Basile and some of his security guards at the heart of Macron's security operation at political events during the 2017 campaign.

One of the meetings scrutinised by the investigators was a large political rally held by Emmanuel Macron on April 17th 2017 at the AccorHotels Arena (formerly the Palais Omnisports Paris Bercy) in Paris. According to Basile this security mission had been coordinated by Benalla and an employee of Macron's En Marché movement Paul H. Basile told investigators he and a team of 15 others had gone to Paris in two hired vans to carry out the work. “Paul H. had told us that they didn't need professional cards [editor's note, showing they were licensed to work as security agents],” he said. “No one was declared,” he added, referring to their work status. Investigators also examined a campaign event held in Marseille on April 1st 2017.

Basile told investigators that he had paid the Paris security team in cash, though he denied having received any cash himself from either Benalla or the En Marche! movement. Instead Basile told Le Monde in July 2019 that he had billed the Macron campaign for his services via a Belgian security firm called ISB. These bills, totally 9,120 euros for the meetings at Marseille and Paris, appear in the Macron campaign accounts. However, the investigators found that ISB was not authorised by CNAPS to carry our security tasks in France.

Fortunato Basile also told investigators that the cash he had used to pay his team had been personally handed over by an executive at ISB identified as Antonio M. The only information that CNAPS could find about him was a death certificate from 2019.

When questioned by Mediapart about the security arrangements for the 2017 campaign, Alexandre Benalla insisted he had done nothing wrong and said that the “issue of choosing the service providers and their payment was not my responsibility but that of those in charge of finances for the campaign and movement” (see his full response in French here).

At the end of their probe the investigators at CNAPS – who included a gendarme and a senior police officer – had detailed a total of 19 administrative failings, plus several alleged breaches of the criminal law, including in particular undeclared work. Their final report, written in 2020, concluded that some services had “in all probability been carried out in illegal circumstances”. But as documents and witness statements seen by Mediapart have shown, once the case was passed up to management it ran into obstacles.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In relation to the alleged criminal offences, the CNAPS hierarchy did not want to refer the case to prosecutors themselves. Instead it took a decision by local detectives in December 2019 for the prosecution service at Grasse in the south-east of France to be informed. The information they passed on has since become part of existing proceedings involving Fortunato Basile. But Basile himself says he has not yet been questioned by detectives over the issue.

As for the administrative failings, at the end of 2020 three senior figures at CNAPS – the local boss in the south east of France, the head of the inspections department and the deputy director of operations - all in turn recommended that the case should be referred to the disciplinary body, the Commission Locale d’Agrément et de Contrôle (CLAC) – for punishments to be determined. They spoke of the “seriousness” of the facts of the case and the “very numerous failings”, in particular the “lack of CNAPS authorisations” and the absence of a professional licence for “five employees”.

Yet despite these recommendations the director of CNAPS, Cyrille Maillet, took the decision to close the case. In the document published here he justified this move by claiming that the “2017 file” was “too old” to be referred to the disciplinary commission.

When contacted by Mediapart Cyrille Maillet said he had taken this decision “even though one agrees that these are serious facts and deserved to go to the commission as my staff said in their opinions”. He added: “It was down to me to determine the balance in this case which, in view of the time delay, ran the risk of not being considered favourably by the law, as with many cases.”

The head of CNAPS repeated his view that the risk of the case being proscribed in law was considerable as it “dated from 2017”. However, this is a highly debatable point. First of all, while the facts may date back to 2017, the case itself was opened later, in 2019, as Cyrille Maillet himself acknowledged when Mediapart went back to him on this point.

But the CNAPS boss's stance is especially debatable given that the rules on legal proscription and delays are very clear. Article L.634-4 of France's code on homeland security states that CNAPS “cannot have facts going back more than three years referred to it if there has been no action aimed at researching, observing or punishing those facts”. This means the 2017 Macron file was well within the proscribable limits, as many different sources agree.

When Mediapart again asked Cyrille Maillet about the legal basis for his decision to close the case, he did not respond on that point. He simply said: “Each year we handle between 1,500 and 2,000 files of this kind and it's very common that the final decision I take is different from the opinion set out by my staff.” The prefect, now aged 57, has had a long career in the civil service. He was an adviser in the office of Claude Guéant when the latter was minister of the interior under President Nicolas Sarkozy, and was later made director of police at the Paris police authority.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

English version by Michael Streeter