Until early February, Fréderique Dumas had run Orange Studio, the film production subsidiary of French telecoms giant Orange, since its creation in 2007, when it was initially launched under the name of Studio 37. In that time she led a series of successful projects, including the coproduction of The Artist (the French film that won the most awards of any in history), The French Kissers (original title Les Beaux Gosses), Gainsbourg: A Heroic Life (original title Gainsbourg vie héroïque) and Welcome.

Mediapart has learnt that in June last year a special advisor to Orange’s CEO Stéphane Richard contacted Dumas to convey what he described as Richard’s opposition to her engagement to coproduce a cinema film about the life of the late and celebrated French fashion designer Yves Saint Laurent, suggesting that this be abandoned.

The reason invoked was an attempt to please Pierre Bergé, a major shareholder of French daily Le Monde. Bergé, 83, a former lover and longstanding friend and business partner of Saint Laurent’s, with whom he co-founded the Yves Saint Laurent fashion house, was known to be hostile to the film. The ultimate aim was, said the advisor, to temper the paper's coverage of the implication of the Orange boss in a highly politically-charged fraud investigation. Dumas declined to pull out of the coproduction. Seven months later, on February 7th, she lost her job for reasons that Orange (previously France Telecom) has declined to comment upon.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In June 2013, Stéphane Richard found himself at the centre of an ongoing judicial probe into a contested arbitration process that saw controversial French tycoon Bernard Tapie awarded 403 million euros of public money in 2008.

The payout was in compensation for the despoiling of Tapie’s assets (see more here and here) by the former Crédit Lyonnais bank when it was state-owned. But the huge sum granted to Tapie was only made possible by a French finance ministry decision to remove the case from the courts in favour of arbitration. That process was decided in June 2007 by Jean-Louis Borloo while he was briefly finance minister following the election as president of Nicolas Sarkozy.

Borloo was a longstanding friend of, and a former lawyer to, Tapie who had publicly supported Sarkozy’s election campaign. After Borloo’s rapid re-appointment as ecology minister, Christine Lagarde, now International Monetary Fund chief, succeeded him and oversaw the arbitration process to its conclusion.

Magistrates are investigating evidence that the payout to Tapie was the result of an illegal conspiracy and in June last year their attentions centred on Stéphane Richard who served at the finance ministry as Lagarde’s chief-of-staff. He was placed under investigation – a legal move that implies ‘serious or concordant evidence’ of implication in a crime – for conspiracy to defraud in relation to the payout. Lagarde herself was questioned in May 2013, when she was made ‘assisted witness’ to the case, a less serious legal status but which nonetheless requires suspicion of her voluntary or involuntary involvement in wrongdoing.

In the space of one month, Le Monde published some 30 articles about Richard’s implication in the case and which were hardly flattering for the high-flying CEO. One, dated June 13th 2013, was headlined ‘Stéphane Richard’s future as head of Orange called into question’. Another, dated June 17th and which recounted emerging accounts of Lagarde’s questioning by the magistrates, ran: ‘Bitter and troubled, Mme Lagarde discharges herself at the expense of M. Richard, her former aide’.

On June 18th, Le Monde, which is published at midday, reported on Richard’s interrogation, under a headline reading ‘M. Richard tells police: ‘It’s Mme Lagarde who gave her agreement’ to arbitration' . In the late afternoon of that same day, Xavier Couture, special advisor to Stéphane Richard, left a voicemail message on the phone of Frédérique Dumas, managing director of Orange Studio, the cinema production company owned by Orange.

In his message, Couture, a former French television executive who was head of Orange's communications department between July 2012 and March 2013, tells Dumas of a plan to dampen Le Monde’s coverage of the events surrounding Stéphane Richard – coverage he alikens to “a drama series”. The scheme was to court the favour of Pierre Bergé who, apart from being one of Le Monde’s three principal shareholders, is also president of its supervisory board. The contents of his message suggest Couture, and Richard, apparently believed Bergé wielded significant influence over the daily’s editorial decisions.

At the time of Couture’s call to Frédérique Dumas, on June 18th 2013, two different cinema films about Saint Laurent’s life were in preparation; Yves Saint Laurent, directed by Jalil Lespert, and Saint Laurent, directed by Bertrand Bonello and which Dumas had decided should be part-funded by Orange Studio. Bergé was opposed to the making of Bonello’s biopic, and supportive of Lespert’s (which was released in January this year). Couture’s message to Dumas was to drop Orange Studio’s financing of the Bonello film.

Mediapart has obtained a copy of the voicemail recording (click audio above), in which Couture says: “Yes, Frédérique, it’s Xavier. Listen, we had a chat with Stéphane on the problematic question of Le Monde in the widest sense before, right, before I try to convince Le Monde’s journalists to be a bit more kind to Stéphane, and not to make a drama series out of a story which we’d much like to see fall away. I think it would be useful to think twice before financing the film on Yves Saint Laurent which is very contested by Pierre Bergé as you know. So, it hasn’t an immediate relation of cause and effect, but I think that it is perhaps not useful just now to attract the ire of Pierre Bergé. So, I don’t know where you’re at with this film. I’m told that Orange Studio would have the intention of producing it, whereas Stéphane is not really in favour. There you are. Listen, you can call me when you want.”

Couture’s message to Dumas was a clear snub of Orange Studio’s supposed independence, which he was apparently happy to override to protect Stéphane Richard’s private interests.

Contacted by Mediapart and questioned about the broad contents of his message, Couture initially denied saying anything of the kind. “It’s ridiculous,” he said. “I was once a journalist, a press editor. Can you imagine the editorial team of Le Monde, and the journalists who follow these affairs, receiving a call from Pierre Bergé with the line ‘calm down’? That doesn’t exist. I’m neither naïve nor an idiot.”

“I have had links with Pierre Bergé for a very long time,” he continued. “He promoted the film about Yves Saint Laurent by Jalil Lespert. He considered that the other film being prepared did not fit in with his idea of Yves Saint Laurent. He permitted himself to call me, telling me amicably that he was not in favour of us backing it.”

Orange sees red over 'political' films

When Mediapart then read to Couture the precise transcript of his message, he replied: “That seems pretty benign to me. If we can avoid getting Pierre’s back up it’s just as well. Stéphane was not in favour of putting Pierre Bergé in a bad mood. We’re all friends with him.”

He insisted he had not given “an order” to Dumas to disengage from the Bonello’s biopic that displeased Bergé. “I asked for a reflection,” he said. “We refelected. We made the film. There is no problem.”

Asked why he had attempted to have Orange Studio abandon the film, why he had mentioned Le Monde in the message and whether this was not a move that placed the private interests of Stéphane Richard before those of his company, which had decided to help the making of the film, Couture replied: “That is an ignominy to which I can only give a formal denial. I will lodge a complaint for defamation. You will have to provide the proof that I said those things.”

Mediapart then presented Couture with an audio copy of his message, after which he appeared to change his attitude, confirming that he recognized his own voice. “I’m not even certain that Stéphane had asked of me anything at all,” he commented. “To try and help Pierre Bergé, I used every argument. I take that entirely upon myself. That will avoid you calling Stéphane Richard. In fact, we’ll settle for this version: I went beyond my rights in saying that Stéphane Richard was unfavourable [for Orange Studio to coproduce Bonello’s biopic], whereas in fact he wasn’t aware [of the project].”

Enlargement : Illustration 3

In fact, Orange Studio continued with its co-funding of Bertrand Bonello’s film, in which it invested 1.3 million euros alongside another production company, Europa Corp, which had agreed to also commit 1.3 million euros. “The scenario was magnificent,” commented Orange Studio’s now-departed head Frédérique Dumas. “Bertrand Bonello is a great director. I couldn’t not make it.”

Meanwhile, Couture told Mediapart that Europa Corp’s director general, Christophe Lambert, had warned him that Orange Studio could not back out of the agreement. Contacted by Mediapart, Lambert explained: “At the time, nothing was signed but orange had given its moral commitment […] This film had to exist despite the pressures [exerted], in the name of a certain cinematic freedom, and without Orange it could not have seen the light of day.”

Pierre Bergé declined to offer any comment at all when he was contacted by Mediapart and asked whether he directly intervened in the matter or whether his wishes were relayed by others.

Mediapart contacted Saint Laurent director Bertrand Bonello, who said he was “shocked” to learn of the events detailed in this investigation. “The whole story of this film was complicated,” he said. “There were lots of interventions. I wasn’t aware of this one. Its a voicemail message that’s clear. No ambiguity. I am dumbfounded. It reaches beyond the cinema, mind. We’re dealing with the private interests of two people, Stéphane Richard and Pierre Bergé. We’re not looking here at all at the business of producing or not a film according to its quality. I am all the more shocked because a few days after this message [was left by Couture on Dumas’ voicemail], I met in July with Pierre Bergé who scolded me [saying], ‘I’d have it in for you for making me out to be a censor, me, the friend of artists’.”

Seven months after that reported conversation between Bonello and Bergé, Frédérique Dumas was ousted from her job as head of Orange Studio, on February 7th. Contacted by Mediapart, a spokesperson for Orange insisted that her departure “has no connection with this affair” –referring to Orange Studio’s coproduction of Bonello’s film - adding that because of legal concerns it was not possible for the company to give the reasons for the ending of her contract.

Mediapart has learned that the attempted interference in Orange Studio’s independent decision-making over the Bonello film was not the first of its kind.

On November 16th 2011, French cinemas began running L’Ordre et la morale (entitled Rebellion in English), a film directed by, and starring, Mathieu Kassovitz. The film was about a hostage taking on the French Pacific island of New Caledonia in 1988, when indigenous Kanak separatists raided a gendarmerie station, killing four officers and abducting 27 others. Separated into two groups, some of the officers were taken to a cave on the island of Ouvéa, where a subsequent French military rescue operation ended in a bloodbath with the deaths of 19 Kanak rebels and two French soldiers. The events took place just days before the second and final round of the 1988 presidential elections in France, which opposed outgoing President François Mitterrand and his conservative opponent Jacques Chirac. The handling of the crisis, and the reasons behind the decisions taken during it, have remained surrounded by controversy and a degree of mystery ever since, and which were explored in L’Ordre et la morale (a Radio Australia interview with the director can be found here).

On December 1st 2011, two weeks after the release of Kassovitz’s film, a meeting was held by the management board of Orange’s cinema production subsidiary Studio 37 - renamed Orange Studio in 2013. Board members present that day included its chair, Christine Albanel, appointed in 2010 as head of Orange’s internal and external communications department (and succeeded by Xavier Couture in July 2012) and who previously served as French culture minister from 2007 – 2009. Her lengthy political career is marked by her closeness to Jacques Chirac, serving in his inner cabinet of advisors when he was prime minister, when she was also his speech writer, and after he became president. Also present was Gervais Pellissier, deputy CEO of France Telecom-Orange and a close ally of Stéphane Richard, as well as Elie Girard, director of the telecoms giant’s department of strategy and development.

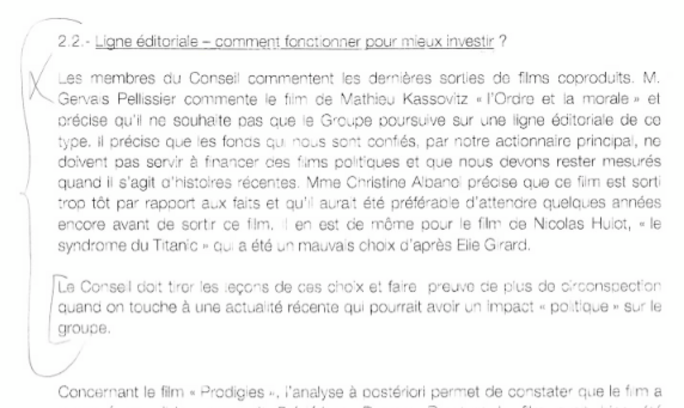

Mediapart has obtained the minutes of the meeting (see above), which include the following extract:

“The members of the board comment on the latest coproduced films. Gervais Pellissier commented on the film by Mathieu Kassovitz, L’Ordre et la morale, and made clear that he did not want the group to continue with an editorial approach of this type. He made clear that the funds that are given to us, by our principal shareholder, should not serve to finance political films and that we should remain measured when dealing with recent happenings. Christine Albanel made clear that this film was released too early with regards to the events and that it would have been preferable to have waited a few more years before releasing this film. It is the same case with the film by [French ecologist] Nicolas Hulot Le Syndrome du Titanic, which was a bad choice according to Elie Girard."

"The board must draw lessons from these choices and demonstrate more caution when dealing with recent events which could have a ‘political’ impact on the [Orange] Group.”

Today, Frédérique Dumas, who took part in the board meeting, admitted that she obeyed the order. “In the two years that followed, I was proposed, for example, a film about a candidate for the [French] presidential elections, and one about [the] Karachi [affair],” she recalled. “I knew that it was impossible to produce them.”

“Studio 37 was created by [former France Telecom CEO] Didier Lombard, who stood by the editorial independence of the subsidiary,” added Dumas. “Nothing concerned the group. Under Stéphane Richard, that independence was ended.”

Questioned by Mediapart, Christine Albanel, who now serves as an executive director of Orange in charge of its cultural and Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) programmes, began by denying any interference in Orange Studio’s editorial choices. “According to my memory, there was a discussion before funding the Kassovitz film, that’s all,” she said. “But we placed no obstacle. And one can absolutely not say that there was a formal decision to avoid political films.”

Asked how it is possible to consider that, 25 years after the events, it is too soon to produce a film about the bloodbath in New Caledonia, she replied: “There is the time span of history and a more immediate time span. However, we didn’t prevent the film from being produced. That proves that there was no censorship. But it is a film that didn’t find its audience. There are perhaps reasons for that.”

Albanel said she could not remember any instructions being given on the subject of political films. “I don’t remember that, and even if there was a discussion to say ‘right, it didn’t work, it was a bit sensitive’ – so what?” she commented. “We are also allowed to have wishes, preferences, want to reach the larger audience. If there were no other political films [after those of Kassovitz and Hulot], it’s because we weren’t proposed with any.”

'Big groups have no interest in funding these projects'

Xavier Couture, a member of the management board but who was not present at the December 2011 meeting, said he was shocked at the suggestion that the board had wanted Orange Studio to refuse coproduction of political films. “I have never heard any talk of that, never,” he said. “The rules of governance of the studio leave a total independence for Frédérique Dumas and I can’t see the company making such a stupid decision. It’s impossible. By definition, cinema recounts life in general, sometimes life in sink estates, and so politics are directly associated with a cinematic project […] No-one has ever challenged the editorial choices of Frédérique Dumas.”

“I don’t know who’s been telling you such jokes,” he added. “At the time of the films by Kassovitz and Hulot, the management board expressed astonishment at the paltry financial results but not about their political character. Not on the substance. Can you imagine a company like ours, quoted on the stock exchange, whose CEO is high-profile, and which has a coproduction subsidiary, busy itself with playing politics, with editorial choice?”

After those comments, Mediapart read the extract of the minutes of the December 2011 board meeting to Couture. “Orange is a company whose shareholder of reference is the state, a company which has above all a vocation to serve the country’s infrastructure by equipping it with networks. It is therefore very complicated to have strong political opinions that could be in opposition with one or another political player who, meanwhile, is associated with the life of the company. It’s complicated, because you always finish up by annoying someone. A work that has a strong bias runs the risk of being in contradiction with one opinion or another, with one or another party, political choices or administrations.”

“I remember CB 2000, the cinematic subsidiary led by [French giant construction company boss] Francis Bouygues, it was the same. They made few political films because the company was involved on markets that went to big companies. That seems to me quite legitimate.”

Contacted by Mediapart and presented with the extract from the Studio 37 board minutes, Mathieu Kassovitz commented: “What surprises me, is that Hulot and me succeeded in making our films. The big groups have no interest in financing these types of projects which bring no returns and which place them in difficulty because their bosses are friends of, or work with, political figures. I never had a problem with Orange. I now discover [what went on in] the wings. That’s how things are.”

Nicolas Hulot described the minutes of the December 2011 Studio 37 board meeting as “appalling”. The environmental campaigner, who was once a maker and presenter of nature and wildlife films on television, said he felt sorry for those directors who were turned down after his film was made. He said he never received any feedback from Orange about his film, which was a stark documentary about the degrading of the environment and destruction of eco-systems. “To all evidence, they didn’t expect such a scathing approach to our society,” he said of Orange. “I saw very well that if they had known they wouldn’t have come along.”

Frédérique Dumas has been replaced at the head of Orange Studio by Pascal Delarue. He was also present at the December 1st 2011 board meeting in his role as deputy general director of Orange’s production arm. Several film producers contacted by Mediapart claimed the rules governing Orange Studio’s funding committee have been modified. Mediapart understands that, currently, financing decisions are now taken by a majority vote of the management board, upon which the staff of Orange Studio have a minority vote. Orange refused to offer any comment on this, arguing that no difference is made between any of the group’s staff.

“With a majority vote, I wouldn’t even have been able to make The Artist, a silent black-and-white movie which no-one would have believed in,” commented Frédérique Dumas.

-------------------------

English version by Graham Tearse