The murder of 11 French engineers in a bomb blast in the Pakistani port of Karachi in 2002 is the object of an ongoing judicial investigation in France with ramifications that threaten to engulf president Nicolas Sarkozy.

This complex affair begins with the 1994 sale by France to Pakistan of three Agosta attack submarines, which the murdered engineers were building in Karachi when the minibus carrying them to work was bombed on May 8th, 2002. The French investigation into their deaths is now working on the theory that the attack was carried out in revenge for the non-payment by France of kickbacks promised to local intermediaries to secure the submarine sale.

Investigations into the kickbacks have found evidence suggesting some of the significant sums of money set aside for the bribes were also destined, via complicated routes, to return to France to illegally fund the 1995 presidential election campaign of former prime minister Edouard Balladur. His campaign spokesman was Nicolas Sarkozy, who also served under Balladur as budget minister.

In October, following a lawsuit filed by relatives of the murdered engineers, investigating magistrate Renaud van Ruymbeke, specialised in financial crime, announced he was to launch an investigation into allegations that commissions from the submarine deal were channelled into a company set up with Sarkozy's approval.

Both Balladur and Sarkozy have firmly denied the claims. But a number of incidents hindering the enquiries of Paris-based magistrate Mark Trévidic, incharge of investigations into the engineers' murders, have served to raise suspicions that the French authorities are deliberately blocking the case, including refusals to transmit key official documents relative to the investigation.

Central to the theory that the Karachi attack was in revenge for France blocking further payment of the network of kickbacks, is that the sums were ordered to be blocked immediately after the 1995 election to the presidency of Balladur's rival, Jacques Chirac. This, it is suggested, served to snuff out Balladur's hopes of funding a base of support that would continue to challenge Chirac.

In 1995, Chirac succeeded socialist president François Mitterrand who had served two successive terms in office. Mitterrand's remarkable 14-year reign, which remains the longest of any French president1, saw him twice share power with conservative Right governments, as was the case when he 'co-habited' with prime minister Edouard Balladur, between 1993 and 1995. It was during that period, in September, 1994, that France negotiated the sale to Pakistan of the three Agosta submarines.

Four months after the deal, in January 1995, while Chirac, the RPR Gaullist party candidate, was already well into his election campaigning, Balladur, formerly a leading RPR figure close to Chirac, publicly announced he, too, would run. He rallied the support of several Gaullist politicians, notably including Nicolas Sarkozy who became his campaign spokesman.

Despite an early lead over Chirac in opinion surveys, Balladur finally polled less than Chirac in the first of the election's two-rounds. Chirac went through to a play-off against Socialist Party candidate Lionel Jospin, and Balladur effectively entered a political wilderness, unable to build a party of support, and from which he never professionaly recovered.

Once the election was over, the campaign expenses of each candidate were to be scrutinised by the nation's highest constitutional authority, the Constitutional Council, to ensure that they complied with electoral law.

But what was not known at the time was that the Constitutional Council's own investigators had raised serious doubts about some of Balladur's election finances and urged its members to reject those accounts. Now for the first time, Mediapart has reconstructed the events of that year and asks the question: how could the Council, the guarantor of the propriety of presidential elections, have approved accounts considered to be in breach of the rules by its own investigators?

It all started on July 12th, 1995, when the Council's president, former French foreign minister Roland Dumas, chose the team of ten 'assistants' who between them would go through the presidential campaign accounts that had just been declared. These high-ranking civil servants were senior judicial officials ('maîtres des requêtes'), at the country's top administrative court, the Council of State, and judges (conseillers référendaires) in the Court of Audit overseeing public accounts. They carried out the investigation work on their own.

The accounts they examined included those of Edouard Balladur, as well as the Socialist Party candidate Lionel Jospin, beaten in the final, second round, and the victorious Jacques Chirac who became president on May 17th.

--------------------------

1: Mitterrand's two terms of office were two, seven-year terms. While Jacques Chirac also served two terms, his second was a five-year term, after a change in French constitutional law limiting presidential mandates to five years.

Major discrepancies

Their task in examining the accounts was far from simple. The investigators had no real power of investigation, certainly not those of a police detective. Their powers were limited to asking, if not begging, for 'all relevant information' or 'documentation relating to receipts and expenditure' from the candidates or third parties.

This lack of real power contrasted with the huge issues at stake; if the accounts of Jacques Chirac were rejected, for example, his election would quite simply be annulled. And if the accounts of one of the losers were thrown out, they would lose their right to have part of their election expenses reimbursed by the state. Which in reality would mean they would face financial ruin.

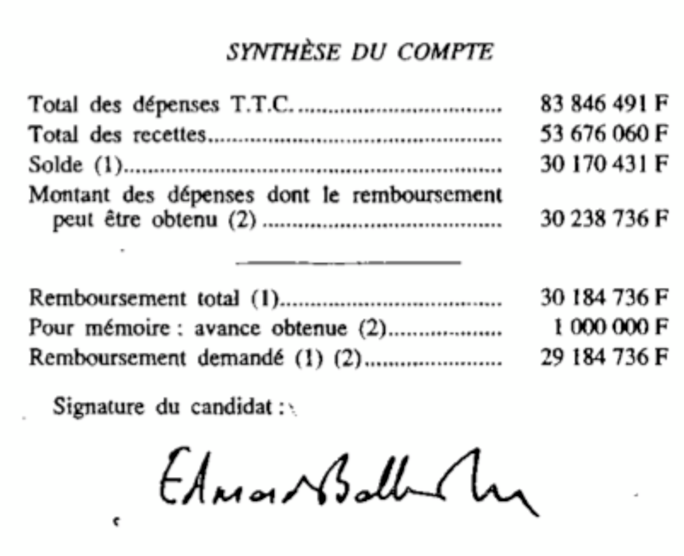

Three investigators examined the file of former prime minister Balladur, who had handed in the following accounts (see below) for his 12 months of campaigning:

Translated into English, the above document reads:

Total expenditure (tax included) 83,846, 491 francs

Total receipts 53,676,060 francs

Balance: 30,238,736 francs

Total reimbursement claimed 30,184,736 francs

For the record: advance received 1,000,000 francs

Reimbursement requested: 29,184,736 francs

Candidate's signature

Edouard Balladur

The investigators were soon struck by two major discrepancies. First there was a bundle of expenses that was not accounted for in the 83.8 million francs (about 12.74 million euros) total expenditure that had been declared. It should be pointed out that the legal limit on expenditure per campaign for the first round of voting had been set at 90 million francs (about 13.7 million euros). The second discrepancy was that there was no proof of where a cash payment of 10.25 million francs (about 1.56 million euros) had come from. This was paid into the bank account of AFICEB the association used for the Balladur campaign finances on April 26th, 1995, in large-denomination notes.

From the end of July, the civil servants had had an exchange of letters with the candidate's representative. Balladur himself never replied, despite several registered letters addressed to him in person.

At the end of their investigation the civil servants delivered their verdict. They judged it to be vital to be able to "re-establish an exhaustive account of the expenses", in other words to re-introduce into the accounts the millions of francs that corresponded to public meetings, trips overseas, renting of electoral headquarters, security costs for meetings and opinion polls. With these taken into calculation, the ceiling on campaign spending was breached.

In relation to the income that was unaccounted for, the investigators wrote in their report: "The candidate manifestly does not know what line of argument to use to answer questions [raised by the deposit of 10.25 million francs] which lacks all supporting documentation'. So where did this cash come from? From secret funds at the French Prime Minister's office, Matignon? From a secret financial trail? If not, why were so many notes paid in at the same time?

When asked about this, Edouard Balladur's representative gave two explanations. One was that the money came from "various sales of gadgets and tee-shirts as well as from flag day collections carried out during rallies and public meetings". The second reason was that the cash raised was "put into a safe box and paid into the bank account altogether at the end of the campaign to avoid the transport of money".

The investigators retorted that the campaign team should have detailed "rally receipts for each rally" and have produced "a note summarising the objects sold" as other candidates, like Lionel Jospin, did. In the end they gave no credence to the idea that the receipts had been kept safe and then paid in all in one go. They found that other cash sums had been "regularly paid into the bank account". This had happened no less than 22 times between March 13th and April 14th, 1995.

The civil servants even allowed themselves a little irony in their report; "It's difficult to see a former minister of finance1 ...leaving up to ten million [francs] dormant in a safe rather than investing it to earn some interest" they wrote. In their view, Balladur's team had produced "no indications of proof" in relation to the origins of the money. They recommended the "rejection" of the accounts in their final report.

-------------------------

1: Edouard Balladur was Minister of Economy and Finance under prime minister Jacques Chirac's government, between 1986 and 1988.

'All that work for this!'

The crucial day arrived in October 1995, when the chief investigator had to present his conclusions to the Constitutional Court at the rue Montpensier in Paris. He entered into the Council's large chamber and sat in front of the nine 'Sages', or 'wise men', as the Council's members are known, who were seated in a horseshoe around the table. They alone had the right to vote on the issue.

The investigator handed out his 'draft decision'. Most of the Council members had not had access to the file from the initial stages and so this was the first time they discovered that the rejection of Edouard Balladur's accounts was being recommended. In front of a very concerned Council, the senior civil servant stressed the dubious receipt of 10.25 million francs and the many 'omissions' in relation to expenditure. At the end the president Roland Dumas suggested to the investigator that he go and revise his work.

The reason was that the 'Sages', a majority of whom had been nominated by the Left, felt it was unthinkable that they could follow the recommendation and reject the accounts. For one thing, they baulked at the idea of ruining a former prime minister. For another they compared Balladur's accounts with those of Jacques Chirac, whose expense declarations had also caused them enormous problems. Eventually Chirac's accounts had been papered over and approved, as in their view there was not enough of a legitimate reason to annul the election of a president of the Republic who had been in office for five months and who had been chosen by 16 million French voters. So when it came to the Balladur file, the Constitutional Council, beginning with Roland Dumas, believed it had no choice but to give a seal of approval.

However, the lead investigator on the Balladur accounts resisted. When he returned later in the day, he had certainly modified his report, but not enough for the Council's liking. He was sent away yet again. In the end the deposit of the 10.25 million francs was forgotten about, and the civil servant suggested bringing back into the accounts just six million francs of the extra expenditure. This brought the amount officially spent by the Balladur campaign to 89,776,119 francs. In other words just 223,881 francs below the legal limit of 90 million, a tiny margin of 0.25%. The expenses of Jacques Chirac had been agreed at 40,000 francs below the legal limit.

Ultimately, only Jacques Cheminade, a marginal candidate from the European Workers Party, had his accounts rejected, over an interest-free loan, providing the Constitutional Court with an opportunity for severerity. One of the investigators, as he left the Council's meeting room, was heard to say: "All that work for this!"

When France's top court 'cleared fraud of highest figures of state'

The investigators showed their displeasure at the Council's decisions in other ways too. To mark the end of the process Dumas had invited not just his eight fellow 'wise men' to lunch, but also the ten investigators. In a snub to the Council's president, they all refused the invitation.

There were signs later that one or more members of the Council felt uneasy about the process. In the months after this episode the Constitutional Council wrote to the government formally asking for extra means and powers in time for overseeing the 2002 presidential election.

Much later, after completing his nine years as one of the nine members of the Council, Jacques Robert, one of the wise men of 1995, revealed in an article what had really gone on; though one has to read between the lines to discover it.

In an article published very discreetly in a book called les Mélanges en l'honneur de Pierre Pactet (published by Dalloz in 2003) Robert, a professor of law and a 'Sage' from 1989 to 1998, wrote of his regret over the "pusillanimity, not to say lack of courage [of the Council] in electoral matters". He wrote: "No one can seriously hold it against the Constitutional Court for not using powers [of coercion] that it did not have. But at least when it is certain about confirmed lies or has clear proof of numerous concealments or underestimates of expenses, it should show itself merciless! And yet we are not even close."

The professor refers to the Council's lack of power in relation to the issues at stake. "If the offender is beaten [in the presidential election] the financial penalties that would be inflicted on them could ruin them personally....So we cover the often clear fraud of certain of the greatest figures of state in the cloak of the country's highest legal body [... ] making up for it less than gloriously at the expense of some minor candidate." Referring to October 1995, Jacques Robert admitted having undergone "some particularly difficult and often intolerable moments".

The head of the Socialist Party group at the National Assembly, Jean-Marc Ayrault, has now asked the Constitutional Council to open its archives and release the documents concerned. These are deemed of importance to the work of investigating judge Renaud Van Ruymbeke, probing the allegations of hidden payments from the submarine sale for Balladur's campaign. However, the Council's current president, Jean-Louis Debré, said the request could only be made by the French government. "And if the government requests that the archives be made public, it will call upon the Constutional Council which will then decide," said Debré, adding he had no powers himself to render the documents public because "they are classified as secret for a period of 25 years."

When contacted by Mediapart, Roland Dumas' secretariat said he "was unable to comment".

English version: Michael Streeter