Macron by the sea, Macron in the fields, Macron in the city, Macron in a village. There is something for all tastes in the campaign pack provided for election candidates from France's ruling party for a mere 2,450 euros. Just two weeks before the first round of the Parliamentary elections on June 12th – the second round is a week later – official campaign literature is adorning the election hoardings. The posters on display show both the design choices and also the very political decisions that have been made by the candidates for the centrist Ensemble coalition. This alliance consists of Emmanuel Macron's ruling La République en Marche (LREM) – now renamed Renaissance – and two allied parties.

Though LREM and those two other parties – former justice minister François Bayrou's MoDem and former prime minister Édouard Philippe's Horizon – have finally reached agreement over the vexed issue of who fields how many candidates and where at the election, a number of those candidates are keen to assert their own identity in their local campaigns. This has not escaped the attention and ire of senior LREM figures, including the president of the National Assembly Richard Ferrand. On May 12th he complained in the candidates' Telegram messenger group: “I'm writing to tell you of my astonishment at discovering on social media that many candidates are omitting to feature the face and/or the name of the president on their campaign posters.”

Ferrand continued: “Our election depends first and foremost on our ability to get out the president's vote. In this respect omitting this designation is a mistake that could put at risk each candidacy and thus the creation of a strong majority. In our collective interest this needs to be put right as a matter of urgency.” This knuckle-rapping message provoked some lively reaction inside the party, forcing the LREM's elections coordinator Grégoire Potton to put out his own, rather less pushy message.

In it Potton wrote: “Ultimately it's for you and your teams to decided on your campaign literature. But it's important that you should be identified as the official candidates of the presidential majority, supporters of the president. That's why our strong recommendation is to use the literature that's been offered to you as a starting point.”

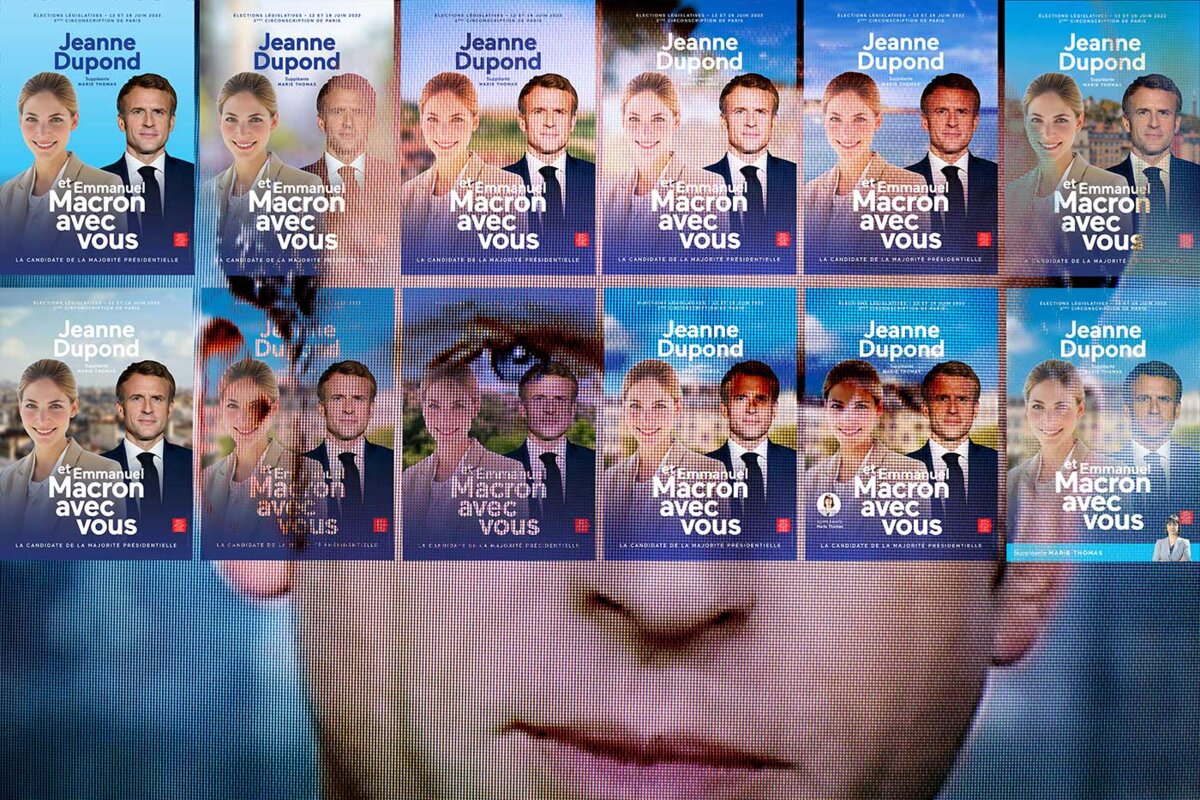

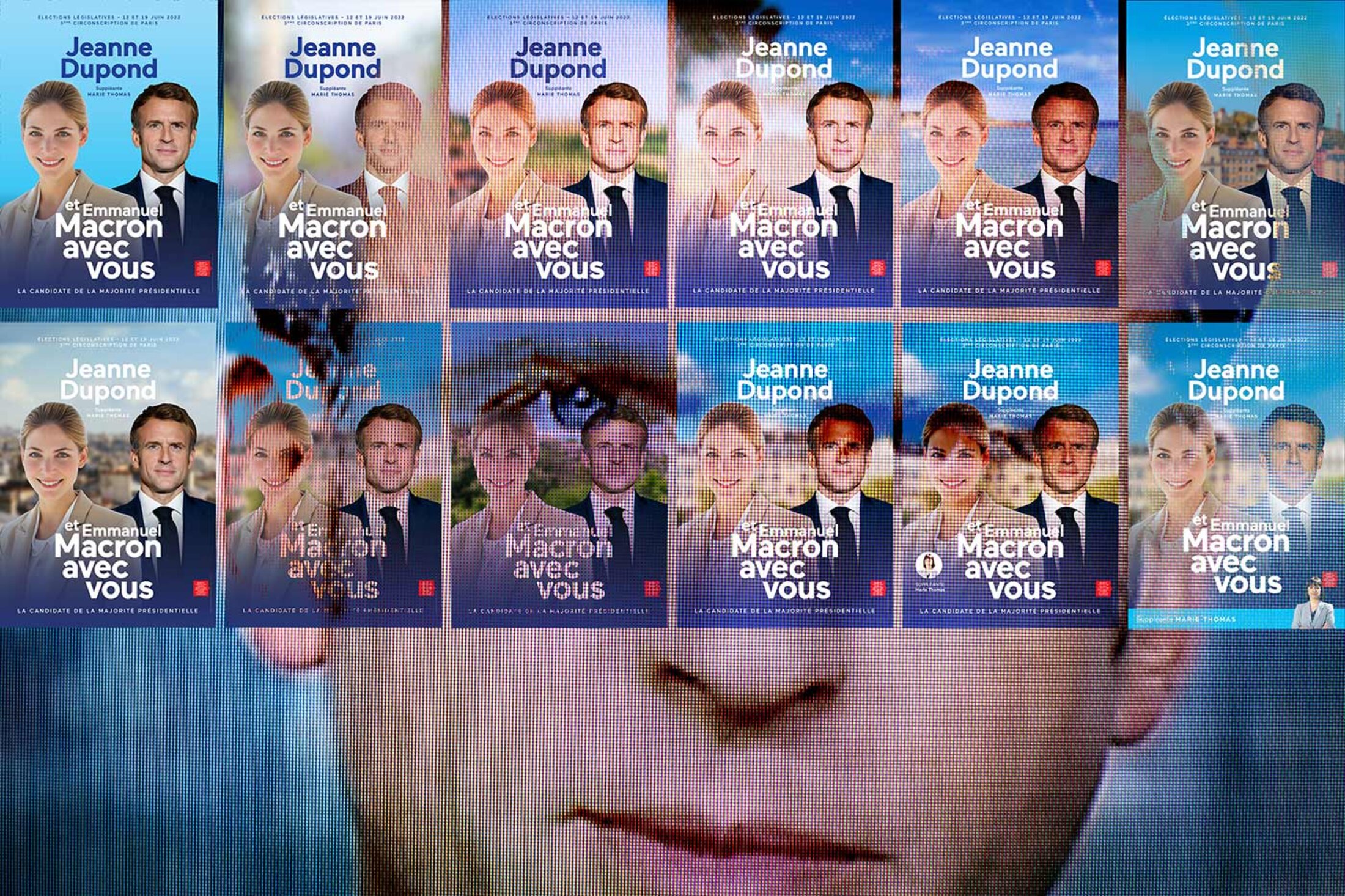

Enlargement : Illustration 1

This campaign literature, seen by Mediapart, bears an uncanny resemblance to the model documents used in 2017 with such evident success; Macron' party and its allies won 350 of the 577 National Assembly seats at that election. They feature Macron's image next to 'Jeanne Dupont' and their substitute 'Marie Thomas', with the actual names and images to be filled in by the candidates and their replacement (in elections for the National Assembly candidates nominate a substitute or 'suppléant' who would take over from them in case they are made a minister or are unable to continue in office).

Using Macron's name and image in this way is, however, precisely the problem for several candidates of the current ruling majority and its allies. After being castigated during the last Parliament as “Playmobil MPs” or MPs who just stuck automaton-style to the party line, and after repeatedly being told that a “goat would have been elected on the Macron ticket”, and that they owed their election simply to the president's photo on their campaign poster, some of them have opted to do things differently this time. “I support the president 3,000% but I'm liberating myself,” said LREM candidate Alexandra Valetta-Ardisson. “I want to show that I wasn't just someone who'd been imposed on them five years ago.”

The sitting MP, who is standing for re-election in the 4th constituency in the Alpes-Maritime département or county in the south east, can no longer stomach taunts from political opponents that the way in which she first became an MP was in some way “illegitimate”. So for this election she has chosen to appear alone on her poster, accompanied solely by her suppléant whose photo is on the reverse side of her leaflet. There is no mention of Emmanuel Macron. “I've laboured and toiled for five years,” she said. “If I'm elected I would like it to be for me. If the voters place their trust in me it will be because they've chosen the right candidate in the area.”

Fear of the Left and far-right

That is also the option chosen by Philippe Hardouin, an opposition town councillor at Ivry-sur-Seine in the south-east suburbs of Paris, and president of En Commun, a movement that is part of the current ruling majority. He is a candidate in the 10th constituency in the Val-de-Marne département where he is standing against the incumbent Mathilde Panot from the radical left La France Insoumise (LFI). An economist by training, Hardouin thinks that the “fight for the legislative elections” cannot simply come down to being on a “poster” next to the newly-elected president, as was the case in 2017.

Philippe Hardoiun says that in this département in the Paris region – a region where the LFI candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon arrived top in the first round of the presidential election in April with 32.67% of votes cast – they had to “do more” than that. He said: “The constituency has four towns afflicted by social divide. So we have to stand for the manifesto on which the president was elected but also bring forward other powerful proposals. A Member of Parliament isn't just there to approve the executive's decisions, they're also someone who fights for more.”

About a hundred kilometres to the west, in the 2nd constituency in the Eure département, the sitting LREM MP Fabien Gouttefarde is also having to take account of how the vote went locally at the presidential election. But his problem is not so much the candidate from the leftwing alliance NUPES – the Nouvelle Union Populaire Écologique et Sociale - which includes the LFI, but from the far-right Rassemblement National (RN). In this département in the Normandy region the RN's presidential candidate Marine Le Pen came ahead of Emmanuel Macron in the second round of voting, attracting 51.38% of the votes cast.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

So unlike in 2017, Fabien Gouttefarde has chosen not to use the cut-out photo of Emmanuel Macron on his official poster. “It's a debate we've had for the last year within my campaign team,” he explained. “I hesitated a great deal but I don't regret my decision. Had I been a candidate in the Yvelines [editor's note, a département west of Paris where Emmanuel Macron attracted 71.05% of votes cast in the second round of the presidential election] or in the Hauts-de-Seine [editor's note, a département between Paris and Yvelines where Macron picked up 80.39% of the votes cast] doubtless I wouldn't have done the same thing.” However, he has put the president's name on his election literature “because, after all, people have to know whom I support”.

The outgoing MP says that “a lot has changed” in the five years since the last Parliamentary election. “In 2017 we were walking on water, it's more difficult now,” he said, acknowledging that in places he plays upon a “certain ambiguity” even though the words “presidential majority” feature on all his campaign material. But to avoid waving a “red rag” in certain parts of his constituency, the sitting MP has produced two different leaflets; one with just his photo “for rural areas”, and the second with the head of state on it “for the towns”.

I'm not in politics to be a clone.

In the Alpes-Maritime the sitting MP Alexandra Valetta-Ardisson says that it will “perhaps be a little less provocative without Emmanuel Macron's photo” while insisting that is “not the main reason” why his image is missing from her campaign poster. While it is true that her area is not that favourable to the president – he only beat Marine Le Pen by 0.26 of a percentage point there in April's election – that had “also been the case in 2017”, she points out. That did not stop her winning the seat then with a 52.74% share of the vote.

On the island of Corsica the major of Ajaccio, Laurent Marcangeli, is a candidate for the ruling majority standing on behalf of Édouard Philippe's Horizon party, which is fielding a total of 58 candidates. He, too, is campaigning without a political label. “I've always done that, even when I was with the UMP,” he said, referring to the rightwing party which is now called Les Républicains. “We're in a region where highlighting the candidate as a person works much better than labels. I'm not in politics to be a clone. I'm always very clear subsequently about my political commitment.” Indeed, the former prime minister Édouard Philippe came for the opening of his campaign headquarters on May 16th.

At the presidential election in April the big winners were Marine Le Pen and the abstention rate. But the major of Ajaccio knows that outside of that national election the main momentum here is with the Corsican nationalist movement. That is why he wants to embody a candidacy that is “first and foremost for Corsica”. He feels this message is even more important because the political context has changed from from five years ago. “You can't say that the atmosphere is comparable to that of 2017,” admits Laurent Marcangeli, referring to recent events and protests on the island.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Violette Spillebout is standing for Parliament for the first time and in her constituency in the Nord département in the north she, too, is placing the emphasis on a local campaign under her name. Once chief of staff to the former high-profile mayor of Lille, Martine Aubry, Violette Spillebout's name is already known in the region since the local elections of 2020, when she stood against Lilles's socialist mayor. In the last days of the campaign, however, she will use the campaign literature provided by the LREM, something made easier by the fact that she is standing in a “favourable constituency”, the 9th constituency in the Nord.

Aurore Bergé, who is standing for re-election in the 10th constituency in Yvelines, is another high-profile figure. Unlike in 2017 Bergé, who is often in the media, is appearing on her own in her election posters this time around. “It's a question of political maturity,” she said. “No one doubts than I'm a Macron supporter. Had I been standing for the first time I'd have used Emmanuel Macron's photo. In any case, the only question that the French people are asking is: do I give the president of the Republic a [Parliamentary] majority or not?”

All the candidates contacted by Mediapart obviously shared the same goal, that of giving the head of state a “strong and clear majority” in the National Assembly for the second time in a row. But if that is achieved, the new majority will not look the same as the 2017 version. A clue to this comes from those Ensemble candidates who have swapped a photo of Emmanuel Macron in their campaign material for that of his former prime minister Édouard Philippe. “It seemed more logical to me and I wanted to be transparent with the voters,” said one of them, who asked for their name not to be used.

A more politically-diverse ruling majority on the cards?

This anonymous candidate said that the president provokes an “irrational hatred” in some areas, unlike his former prime minister who enjoys a popularity which, his critics argue, is equally “irrational”. In Édouard Philippe's home northern port city of Le Havre it is perhaps understandable that the incumbent MP Agnès Fimin-Le Body, representing the Horizons party, is using the former prime minister's image on her poster.

The idea of a single party - or even one united Parliamentary group - which was outlined by Emmanuel Macron between the two rounds of voting in the presidential election, was in the end scuppered by his allies from the outgoing ruling majority. Indeed, the political differences that slowly began to emerge over the last five years are already visible in the choices being made in the current Parliamentary election campaign. This points to far more interesting political debates over the next five years than those seen in the last Parliament, which according to LREM MP Hugues Renson was gripped by the “paralysis of the majority's discipline”.

In comments published in February Renson, who was the vice-president of the National Assembly and is not standing for re-election, expressed his regret that the Assembly had “come to be considered – and sometimes considered itself – as a rubber stamp for decisions made elsewhere”. That is, however, the mode of operation that best suits the president. He may have promised to revive Parliament's role but during his first term of office he did all he could to limit its power. He did so by relying on MPs who thought that they owed him everything – starting with their freedom.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter