Widely acclaimed French-Swiss cinema director Jean-Luc Godard, regarded as one of the greatest filmmakers of his generation, whose innovative style made him one of the leading directors of France’s revolutionary New Wave cinema movement, has died in Switzerland on Tuesday in an assisted suicide. He was aged 91.

His legal advisor Patrick Jeanneret told news agency AFP that Godard "had recourse to legal assistance in Switzerland for a voluntary departure as he was stricken with 'multiple invalidating illnesses', according to the medical report". Jeanneret underlined that in Switzerland assisted suicide is both legal and strictly regulated.

Godard, who began his career as a film critic, burst onto the scene in 1960 with Breathless (original title, À bout de souffle), starring Jean Seberg and Jean-Paul Belmondo, shot with a constantly moving camera and with scenes that were partly improvised, a style that marked what was to become known as the New Wave. The prolific director, whose early work following Breathless notably included A Woman is a Woman, The Little Soldier, Contempt and Pierrot le Fou, shot a further 44 feature films, right up to 2018’s The Image Book.

In December last year, Mediapart published its last interview with Godard (11 years after a two-hour videoed interview), when Ludovic Lamant and Jade Lindgaard visited him at his home close to Lake Geneva in Switzerland, which we re-publish below.

*

An encounter - with a difference - with French film legend Jean-Luc Godard

The current wave of political, environmental and social upheavals appears to be marking the ending of an era across the Western world. Mediapart was keen to visit the legendary Franco-Swiss film director Jean-Luc Godard, whose films are an unrivalled chronicle of both the world's beauty and its problems, to get his take on events. However, nothing about the interview with the filmmaker at his home in Switzerland went exactly as planned. Ludovic Lamant and Jade Lindgaard describe here the encounter that ensued:

It did not take long for us to realise that the interview would not take place in the way we had hoped. When we arrived at Rolle on the shores of Lake Geneva in Switzerland one rainy day in November we were sure of just one thing: that Franco-Swiss filmmaker Jean-Luc Godard, who has just celebrated his 91st birthday, had agreed in principle to an interview, and not one that was simply part of a film release marketing campaign.

Some eleven years after he agreed to a first interview with Mediapart, and following a subsequent public encounter with him at the Cinéma des cinéastes centre in Paris, this was an opportunity to meet again with a major artist, one whose last film, Le Livre d’image, ('The Image Book') we had found enchanting. We were to meet the director mid-morning for at least one hour, perhaps more, at his home a stone's throw from the water's edge. The rules included no photographs and no camera. The filmmaker had also asked for two of us to interview him, observing a strict “gender balance”.

The meeting with Jean-Luc Godard was arranged with the help of his friend, the Palestinian historian and poet Elias Sanbar, who appeared in the director's 2010 film Film Socialisme. A few days before the interview he told us how Godard was a close observer of the inner workings of French television, and in particular of its news channels.

Given that director Bruno Dumont has only this year released France, whose heroine, played by actress Léa Seydoux, is the star presenter of a news channel very similar to the actual French news station BFMTV, it felt significant that two major filmmakers from different generations were both taking an interest in the ills of French television. We were keen to get Godard's 'take' on all this.

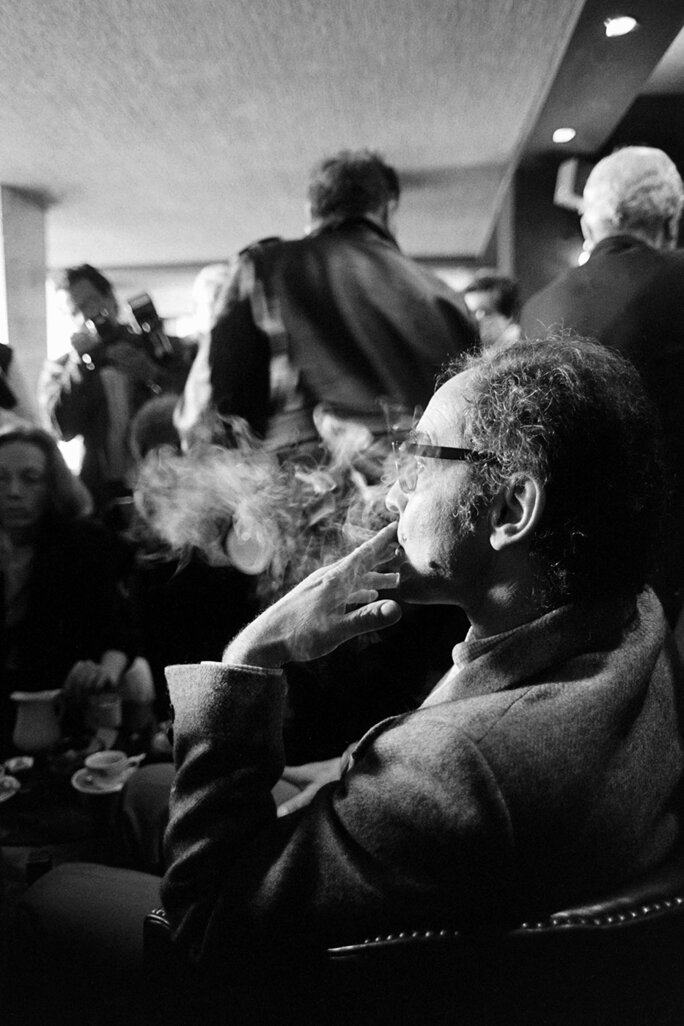

Enlargement : Illustration 1

When we arrived the director greeted us in his living room where everything had been prepared for the meeting: two armchairs had been set up facing his, and there was a small table on which to place our things. Godard shook our hands as we came in. We asked permission to remove our face masks; he agreed and then sank into his armchair, his back to the window. Behind us was a plasma screen, switched off.

To his right, on the wall, there was a huge reproduction of a black and white portrait of a woman, whom to his disappointment we were slow to identify during the conversation: it was of the philosopher Hannah Arendt in her younger years. Meanwhile, the director's assistant Jean-Paul Battagia was listening to the interview from a distance in an adjoining room, sitting on the bottom steps of the staircase that leads to Godard's office and his editing room. It is 10am and the conversation begins.

Mediapart: We're very happy to meet you.

Jean-Luc Godard: Yes, I've wondered why.

Mediapart: You have agreed to this request for an interview during a period that, in political terms, worries us.

J-L. G.: Yes, I do understand.

Mediapart: Ahead of the French presidential election in April, with the rise of polemicist and candidate Éric Zemmour and amid fears that public debate will veer to the far-right..... do the politics of today interest you?

J-L. G.: Why me? I've been out of all that for a long time.

Mediapart: Do you follow the political debates and television programmes a bit?

J-L. G.: Yes absolutely but … I've left classical cinema such as it is. Fundamentally it no longer much interests me, whether it's on television, the big screen or Netflix. It doesn't interest me because it's too flat. As far as I'm concerned the earth isn't flat. For a very long time I have been against, quite against, abuse of the text, abuse of the script and other things. And the affection that I had for classical painting, up to the impressionists, helped me in a way because they were outside newspapers.

[Paul] Cézanne was friends with [Émile] Zola but they inhabited two different worlds. And I'm rather on Cézanne's side. Perhaps Cézanne did care about [Alfred] Dreyfus [editor's note, the Jewish victim of a major injustice in France in the late 19th and early 20th century] but he didn't campaign for Dreyfus like Zola did. And so I won't campaign with you. What's more, I didn't agree to subscribe to Mediapart at the time because that seemed to me to be in opposition with something from the cinema world.

Mediapart: It what way did it seem to be in opposition?

J-L. G.: Because they print on paper or are on television, when they should at the very least make some films or other things... But that's the way the world has gone. And I don't find me interesting. I haven't found myself interesting for a long time. Because people speak to me about me. About what I've done. What's more, I can't speak to them any more, even if they don't speak to me about me. Because I'm forced to speak the language of my fellow citizens.

I realised that I don't look.

And when I say language, it's every language. If we were Czech we'd speak Czech – I still say Czechoslovakia. If we were Russian, we'd speak Russian. If you're French you speak French. But all that, that's the alphabet. And when I saw that Google was going to call itself Alphabet I told myself : “That's it, it's done.” So the great culprit for me, if one has to use the word culprit, or some form of developer, or devil if you're religious, is the alphabet.

Mediapart: Why? The great culprit for what?

J-L. G.: Because you can twist letters – which later became figures – in every sense. If we link that to Cézanne, let's say to the images to use current parlance, well one can survive. If you don't do that, if you just interpret an image, or an image provided like a caricature, there's no point. So I'm quite alone like that, in a prison. Nothing that I say to you is interesting because it's just about me. We should be sitting here and you, if you were in my domain, which is very broad, you'd say to me: “Ah, in what film?” or it doesn't matter, in another film now or in an image from television that you can connect to, you should say “Is it good?”, “Does it not work?”. Instead, you speak to me. That doesn't interest me. I'm being kind because I'm seeing for the last time one of the constituent parts of the Left in France. I still appreciate the Left, but I've left it to one side. It's not interesting. It's not interesting. People confuse language and speech, including science. Of course I still take an interest in all that because I'm still here. So I don't think that we can speak. I don't think we can speak.

*****

At this stage of the interview we could have just accepted the failure that Jean-Luc Godard was clearly pointing to. He had said “I don't think we can speak” twice and the message was clear. But out of a mixture of stubbornness, curiosity, admiration for his works and fascination for the strange situation that was unfolding, we stayed. From that moment on the detailed list of questions that we had prepared was no longer of any use. So were relieved when the filmmaker took advantage of the pause to speak about his dogs.

Jean-Luc Godard: Anne-Marie [editor's note, his wife Anne-Marie Miéville] and I started to take in dogs that we got from refuges – the last was in Spain. Because dogs are interesting. If you look at them, everything is in their look. We don't have anything in the way we look. For a long time I thought I had my own look as a filmmaker, but I don't now think so. You look at me, I look at you but we don't express anything in this look.

Mediapart: A little, surely?

J-L. G.: No, nothing at all. You have an intention behind your look, but when you compare your look, or that of anyone who's on the television, with the look of a dog – I don't know enough about other animals – or let's say a horse or fish, though I don't know enough about them, we're not looking. We see, but we speak about what we're seeing. Animals don't do that. They do have a mouth, however. That's another thing.

You look with your eyes. You're like a camera. I also look. But nothing more, as I speak our language and as I don't speak anything else. So each time you say one more word, it's pointless. I do it out of curiosity, to see what these people are like who say: “We have to change the world”, “We have to be against coal”, or I do it to be like that. It doesn't amuse me, I pity myself that I'm still interested in that. But as I'm still on Earth, and have a few years to live, yes, I do it. That's all.

Mediapart: But we haven't come to survey your soul or to ask you why you did this or that. What interests us is to get something of your take, how you look at the world we're in.

J-L. G.: But I'm telling you, I came to realise that I don't look. Dogs look. I've discovered that I don't know how to look like them. Because I speak straight away. I speak straight away. We've been somewhat cursed ever since the invention of the alphabet. If the devil is in the detail, he's in the details of the 26 letters which, thanks to mathematicians, quickly became billions and billions of figures. That's all I'm saying.

****

The theory that the invention of writing cut humans off from their symbiotic relationship with other living species is at the heart of a magnificent book by the philosopher David Abram, 'The Spell of the Sensual', which has been translated into French. We put this idea and the textual reference to the film director, who promptly put us in our place. “If he just writes, it's not interesting. He does the same as me. One can't stop oneself from talking. You'd be better off being like the wolves and the sheep,” he responded. And he continued: “But nothing that one says is interesting. It's uninteresting. Well, I wanted once again to see people who find something like that interesting, as if I was revisiting a place I'd once been to, to see what had become of them. There you go.”

I don't know why you came – that's why I agreed to it.

We then tried to find out whether living so close to Lake Geneva – which featured in his film Nouvelle Vague ('New Wave') in 1990 – has changed him. To see if this proximity had nurtured an attachment to nature in him. The filmmaker almost lost his temper at this. “But that's got nothing to do with it. You're speaking to me about me, in my opinion it's of no interest to you knowing why I came to Switzerland. You'd have to know my life even better than I do to be able to ask me something about that. Otherwise I'll tell you again what I've said a thousand times in hundreds of interviews.”

A wall seemed to have come down between us. He went over the questions that we had started to raise such as “What does that mean?”, “Doesn't that mean?” and “How would you put it?” And the director commented: “I take all of that on board. Today, at the end of my life, those are wounds for me. They became wounds very early on. Because my bad nature, or my sense of repartee, is in fact a response to a little sting but one which has today become stronger. If I want to check something with a telephone operator from my iPhone someone says to me: 'You can't do that, sorry.' With my sense of repartee, which I haven't managed to get rid of, I say: 'No, you say you're sorry but I'm the one who's sorry.' And then it quickly goes downhill. It's the alphabet. The devil is in the detail.”

We carried on. What did he, a devoted viewer of news channels as we were told, think of the grip that businessman Vincent Bolloré has on a growing part of the French media, given that his companies own news channel CNews, satellite channel Canal Plus, Europe 1 radio, and Prisma Presse? “That's always been the case, whether it's Bolloré or the old ORTF [editor's note, a reference to the state agency the Office de Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française that controlled public television and radio in France in the late 1960s and early 1970s]. At one time I believed in television. I even made films paid for by television. But Bolloré … I prefer to read Le Canard [editor's note, the investigative weekly Le Canard Enchaîné] at the moment...”

When we showed surprise that he did not make a distinction between public control via ORTF and the private ownership of television and radio stations, Godard responded by switching targets. “I no longer speak this language which is fake, I speak it in order to speak with you or do my shopping, otherwise I'm not interested in it.” In relation to the businessman Vincent Bolloré, who is also known for his network of African businesses, even though he may now be on the verge of selling them, Jean-Luc Godard said: “As far as I'm concerned he's too big. Of course it bothers me that he has all these things in Africa. These aren't interesting people. I can't get interested.” Our questions about the media appearances of Éric Zemmour, the far-right polemicist and now presidential candidate, who used to have a regular slot on Bolloré's CNews, produced no response.

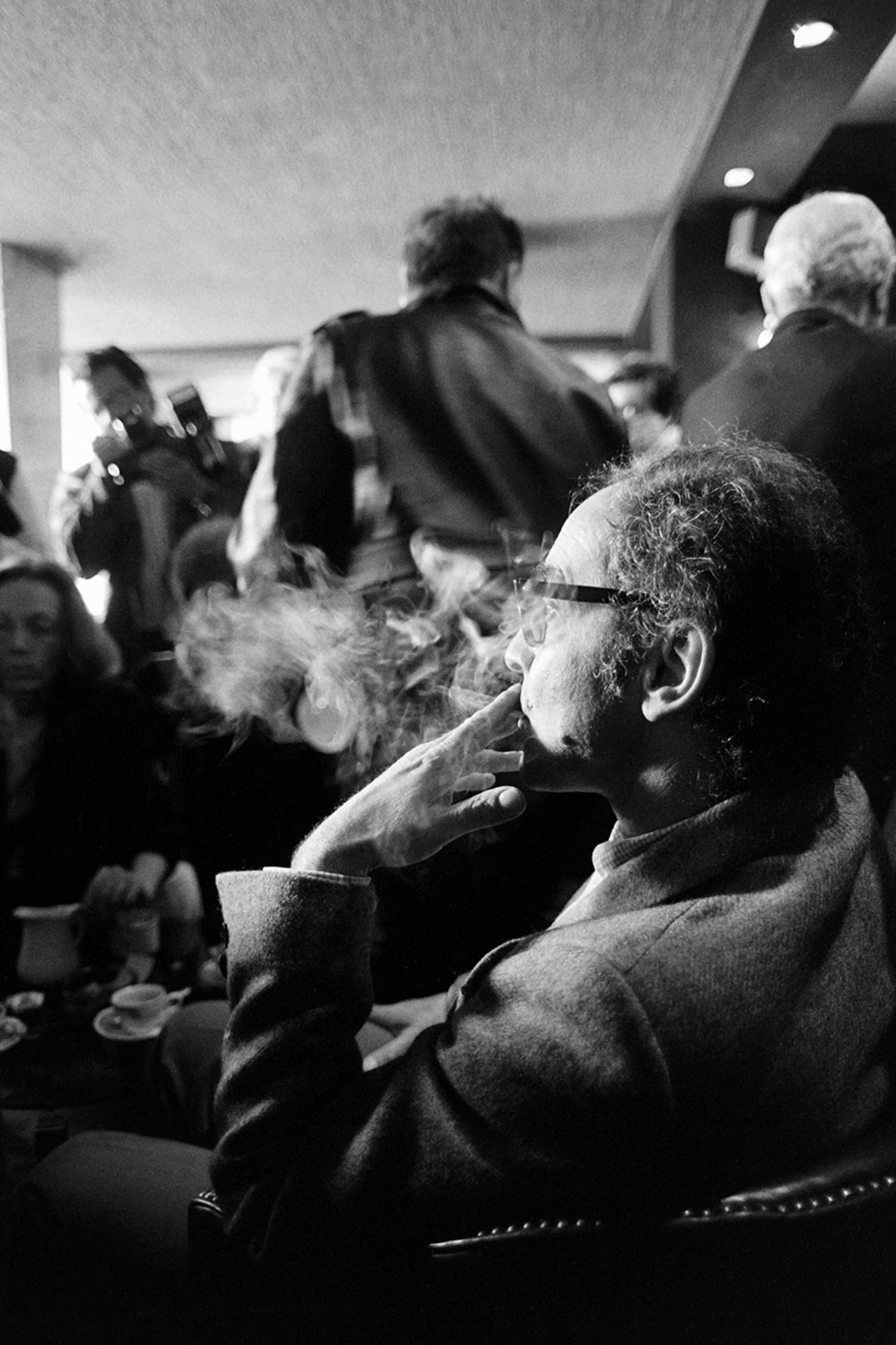

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Mediapart: When you agreed to this interview you let it be known that ideally there should be one male and one female journalist.

J-L. G.: So that at least there was equality.

Mediapart: Why?

J-L. G.: To follow dogma.

Mediapart: Is it dogma or is it something that matters to you?

J-L. G.: I no longer know how to respond. In the past I certainly would have liked to respond. Not now, that's over with. That's not what has to be done. I don't know what has to be done. In one film I got someone to say – it's the film [editor's note, 'Adieu au Langage' in 2014] to which Jane Campion [editor's note, the New Zealand director who was president of the jury at the 2014 Cannes Film Festival] gave a jury prize: “A fact is something that happens. But we mustn't forget that it's also something that doesn't happen.” And as far as I'm concerned, what doesn't happen today is more of a fact than what does happen. If I have to put it like that. Living through it is another matter. All I can say to you today is; that which doesn't happen between us is much more important that what does happen. And that, specifically, Mediapart is only concerned with what is happening. It's always looking for who has received what money. It doesn't look for what the person who received the money didn't do.

*****

In a lovely interview that he gave to the film magazine Cahiers du Cinéma back in 2019, conducted by Stéphane Delorme and Joachim Lepastier, Godard had begun talking about plans for a future film, called Scénario. Shooting on that film has not yet taken place, having been put back because of the health crisis. The director did not want to talk about the likely timetable for the filming (“What difference does it make to you?”). But he did produce a precious object for us, his notebook for Scénario, which was brought down from the first floor of his house at Rolle and which he allowed us to look at and flick through.

You've already met me on another occasion, when we made opposing, contradictory arguments. Now I'm telling you the opposite of nothing.

The notebook contained images, drawings and collages. These include Melencolia I, one of the most famous engravings by Albrecht Dürer. Godard said about the German artist: “In [his novel] 'Old Masters' [the Austrian novelist] Thomas Bernhard says of Dürer that he put nature on the canvas and killed it. It was Netflix already.” There was also a dove perched on a camera, taken from a 1988 film, Ashik Kerib, by Armenian director Sergei Parajanov.

Further on in the notebook, in an excerpt under the heading 'With Berénice', there was a portrait photo of Assa Traoré. “Yes, I was thinking she could do something, to be Bérénice in the end,” said the film director. Speaking about the sister of Adama Traoré - he died at the hands of the police near Paris in 2016 - who has become a leading figure in the criticism of police violence, Jean-Luc Godard said: “I respect and admire her.” Immediately we thought of the Black Panthers whom he had filmed in London in 1968 for his film One + One, known in English as Sympathy for the Devil. But he said nothing more about the French activist.

On the same page a verse from the 17th century French playwright Jean Racine had been copied and modified and now said “so much bitterness separates us” rather than the original line: “In a month, in a year, how will we bear that so many seas separate me from you?” In French there is a play on words here between the French for bitter – amer – and the French for sea, mer. Earlier in the book there is a portrait of Rachel Khan, author of the essay Racée ('Purebred'), published by L'Observatoire in 2021, who is an opponent of the new anti-racist and feminist narratives, and who has just been asked by France's ruling party La République en Marche to work on immigration and secular issues before next April's presidential elections. Why was she there? “I might ask her if we can film her while she is at [news channel] LCI – if it doesn't bother her. Because it relates to what I'm trying to say.”

Did the director see a link between the current protests against police violence and the Black Power movement in the United States of the 1960s? We did not manage to ask him the questions that we had prepared in advance. But we did bring up the name of Omar Blondin Diop, the Niger-born Senegalese revolutionary activist whom Godard had filmed in La Chinoise in 1967, and who had died in detention on the Île de Gorée off Senegal in 1973, and about whom Belgian director Vincent Meessen recently made a film.

Jean-Luc Godard: He died in prison.

Mediapart: His name has featured in recent demonstrations in Senegal.

J-L. G.: Good.

Mediapart: You were one of the first to film him. Do you sometimes think of him?

J-L. G.: I remember how he spoke. He was a friend of my then wife [editor's note, Anne Wiazemsky], he was a student, he died under the regime of Léopold Sédar Senghor...

Godard's most recent film, The Image Book, deals with anti-colonial struggles and the spirit of the Arab uprisings of 2011 runs through it. We still wanted to know if he could relate to the current political upheaval. So we tried one last question on this general area.

Mediapart: Are you moved by the revolts by young people: on the climate, against sexist and sexual violence with #MeToo, against police violence?

J-L. G.: Absolutely, all revolts are good, as was the case in May '68 and other times.

Mediapart: There is a connection between May '68 and today but the characters are different, for example Greta Thunberg …

J-L. G.: I salute them all, I'm with them in my heart of hearts, and also externally, and if she sends me a payment form I'll pay it.

*****

Enlargement : Illustration 3

On the subject of the young climate activist from Sweden Godard also said: “It's great, it's very nice what they're doing at Glasgow [editor's note, during the COP26 climate conference held in November]. Fabius [editor's note, the French politician Laurent Fabius who chaired COP21 in Paris in 2015] wouldn't do that.”

We asked him again about the image of the young girl, then at High School, alone in front of the Swedish Parliament with her banner 'School strike for climate'. He said: “I think she's very good, she has a far bigger public than me and I'm very happy about that.” A little later he quotes “a sentence which one could say to Greta Thunberg: 'We are never sad enough to make the world better'.”

Mediapart: Do you know when you're going to shoot your film that's in planning?

J-L. G.: No. Perhaps it will remain at that stage.

Mediapart: Do you want to film it?

J-L. G.: I think so, a bit, I don't know, I'm a little old, I don't know. But it's for you to say if that interests you or not.

Mediapart: We're eager to know when it will be shot, it interests us.

J-L. G.: But what difference does it make to you? You have no need to see me, no reason.

Mediapart: It's our job to meet people and to hear what they say...

J-L. G.: You've already met me on another occasion, when we made opposing and contradictory arguments. Now I'm telling you the opposite of nothing.

Mediapart: But you agreed to the suggestion of a meeting.

J-L. G.: Yes, it's like visiting places from the past

Mediapart: Shall we stop there? We don't want to upset you.

J-L. G.: I don't know why you came – that's why I agreed to it.

Mediapart: Has your curiosity been satisfied?

J-L. G.: It's convinced me about what I thought of Mediapart.

Mediapart: Which is?

J-L. G.: Each ant works to live as well - or as least badly - as possible. It's a very interesting time, what's happening in France is very interesting for France, it's seriously sick but it knows it, many other regimes or countries don't know it.

*****

We get ready to stop our recording devices and to leave Rolle. But Jean-Luc Godard interrupts us one last time and this time keeps us from going. At the start of the interview he had spoken to us about five phrases that “stay in my memory and which I sometimes repeat in the evening to see if I still remember them”. But by this stage of the encounter, after an hour and thirty minutes of painful toing and froing between us, it has slipped our minds.

Jean-Luc Godard: I haven't told you my five phrases! You forgot, I'm the one who's having to remind you … It helps me if I say them to you. It helps me to see if I still know them.

Mediapart: At least we'll have helped with that.

J-L. G.: Ok. The first is a phrase by [French author Georges] Bernanos in [the essay] 'Les Enfants humiliés' ('The Humiliated Children') or elsewhere. Moreover, I made a short film about it, about Sarajevo ['Je vous salue, Sarajevo' in 1993, usually translated into English as 'Hail Sarajevo', see the link below]: “In one way fear is also God's daughter, redeemed on the night of Holy Friday. She is not beautiful to look at, ridiculed at times, at others cursed, disowned by everyone, and yet, make no mistake, she is present at every deathbed- she is man's intercessor.”

It's a phrase that could absolutely relate to France today, which is afraid. Even CNews speaks about that.

The second phrase is from [French philosopher Henri] Bergson. It was sent to me by a former location manager, I had already cited it, he recited it back to me, then I got Alain Badou to say it in Film Socialisme. It is: “Spirit borrows from matter the perceptions on which it feeds, and restores them to matter in the form of movements which it has stamped with its own freedom.”

I've never really understood the word “perception”, the perceptions of the matter.

The third phrase is from Claude Lefort, who was a philosopher in a small group called Socialisme ou Barbarie ('Socialism or Barbarism') at the time of Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir: “Modern democracies that make politics a separate domain of thought are predisposed to totalitarianism.”

And here is the image of a young woman who later wrote books on totalitarianism.

(At this point the filmmaker shows us the black and white photo of Hannah Arendt.)

This was the time when she was in love with [philosopher Martin] Heidegger. That image is in a film by Anne-Marie [Miéville] that you won't know, which is called Nous sommes tous encore ici ('We're all still here')[editor's note, made in 1996].

After that there's a fourth phrase. Am I going to remember the author's name? To find it I'll tap the name of a book called 'Crowds and Power' [editor's note, published in 1960] into my iPhone.

(Godard's assistant, Jean-Paul Battagia, interjects and says: “I'll do it … Elias Canetti.”)

I put this phrase in The Image Book, it was spoken by my wife. You could say it to Greta Thunberg: “We are never sad enough to make the world better.”

And I'll add a fifth, which is a phrase by Raymond Queneau, whose novels I really liked at the time. This aphorism goes as follows: “Everyone thinks that two and two make four, but they forget the wind velocity.”

(Godard relights his cigar.)

The five phrases, for five fingers, which I have remembered for years, and that I try to repeat to myself, as a reference. I do it automatically, and sometimes I try to think of them a little, to stay with them. In general especially when I'm going to sleep. There you go. You've succeeded in getting me to talk, eh? That's what you wanted.

(With this, the director gets up from his armchair to say goodbye. We leave.)

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter