For the Amazon it was the equivalent of an act of environmental vandalism. The French oil company Maurel & Prom has discreetly withdrawn from the DOM-1 drilling platform that had opened in 2010 in the province of Condorcanqui, in the north of the Peruvian Amazon. So when on May 21st, 2015, inspectors from Peru's environment ministry arrived at the site they discovered the installation, including a base camp and heliport, completely deserted and left under the guard of a local community. The Fortuna 1XD-ST3 wells, as they are officially known, were left “in a state of abandon”, according to the officials. The “pits for the drilling waste are covered and closed”, while the evacuation pipes for the industrial effluent to the rivers are “inoperative”.

The local Awajún and Wampi Amazonian Indians, who have already accused oil firms of having contaminated the rivers and surrounding wildlife, point out that the French firm did not even bother to organise the dismantling of the facilities. Since 2014, and with the backing of Peruvian non-governmental organisations, the Indian communities have been taking legal action against the Peruvian state over the circumstances surrounding the granting of authorisation for the drilling rig in the middle of what is known as Block 116. This is an area of 658,800 km2 of Amazon forest which includes two natural parks – the Santiago Comaina reserved zone and the Tuntanain communal reserve which cover 36.6% and 48.5% of the area respectively – and where 709 bird species have been recorded.

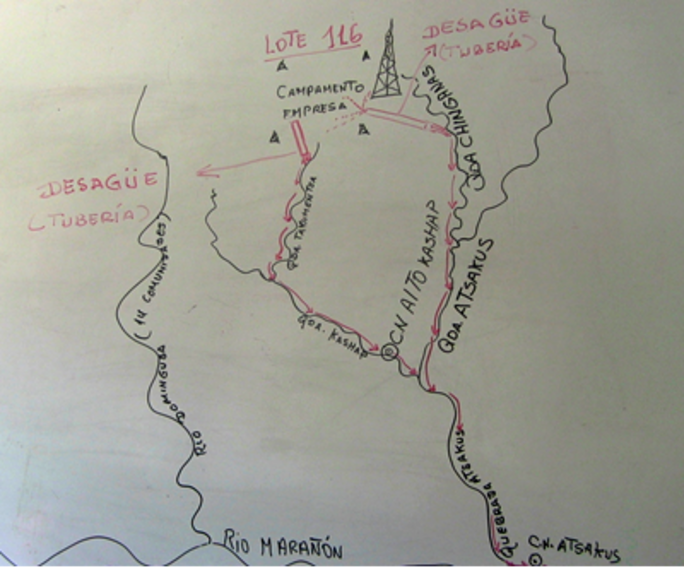

Enlargement : Illustration 1

According to the French development NGO the Comité Catholique Contre la Faim et pour le Développement (CCFD)-Terre Solidaire, and the NGO Sherpa, which defends people against economic crimes, this case reinforces the need to introduce a “duty of vigilance” for multinationals in the way they operate. On November 18th, 2015, the French Parliament's upper chamber the Senate rejected a bill on this issue that had been approved by the National Assembly back in March. The bill aims to make it an obligation to “put in place a plan of vigilance” including “measures to identify and to prevent risks of undermining human rights and fundamental freedoms, of serious material or environmental damage or health risks” that result from the activities of the companies and their subsidiaries. The National Assembly is likely to approve the bill again in the coming months.

Maurel & Prom is a small oil company created through the contacts of its boss Jean-François Hénin, former treasurer of the Thomson CSF defence group and ex-boss of Altus Finances, a subsidiary of the bank Crédit Lyonnais. He earned the nickname of 'the Mozart of finance' before being caught up in a number of hazardous investments made by the bank. In 2006 Hénin pleaded guilty at a federal court in Los Angeles to causing Altus Finance to lie to US regulators during the 1991 takeover of Los Angeles-based Executive Life Insurance Co. The financier then moved into the oil business and obtained his first exploration permits in the Republic of the Congo and Gabon. It is the Gabon which has remained his most important area of operations, with five permits renewed in 2014 – despite the fall in the oil price which has hit the market. In Peru the company signed a joint venture deal with the Canadian firm Pacific Rubiales Corp.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In March 2015 Jean-François Hénin explained: “The second half of 2014 disrupted the entire oil industry, with the collapse of the oil price.” The boss of Maurel & Prom used this to justify the decision to review the firm' ongoing investments and cut its exploration budget by two thirds. “In Peru the drilling of the Fortuna-1 wells has been abandoned,” he continued. “The group does not envisage proceeding with this project during its entry to the third phase of exploration.” Some 75 million dollars were spent by its Canadian partner, who had became the official operator of the drilling site. Even so, Maurel & Prom Peru Holdings, based in Paris with Jean-François Hénin as its chairman, and which still owned the Block 116 drilling permit, posted a loss of 14 million euros at the end of 2014.

It was also in 2014 that the Indian communities in Peru first began their legal action. On January 19th, 2016, the country's constitutional court will examine claims by the Indian associations who say that the right to prior consultation of native peoples, enshrined in the International Convention 169 of the International Labour Organisation which was ratified by Peru in 1994, was not respected before the award of a permit for the exploration of and production in Block 116. Four Awajún and Wampi leaders, helped by the Amazon Center of Anthropology and Practical Application association (CAAAP), accuse the state of a complete lack of consultation.

The Indians also claim that the authorities breached Peru's own environmental rules by only holding a simple information meeting in Santa Maria de Nieva, the state capital of Condorcanqui, in March 2007, some 14 months after the exploration and production permits has been granted. And that meeting took place in the absence of community leaders. The mass arrival of so many oil companies had been one of the reasons for the Amazonian strike and the blocking of the Marginal de la Selva, a major highway through the Amazon, in May and June 2009. This major social movement finally ended on June 5th, 2009, when Peruvian police cleared the road, leading to the death of at least 34 people, including many police officers.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

“The appeal undertaken by the communities could, if it succeeds, reopen a consultation process,” says Morgane Laurent of CCFD-Terre Solidaire. The abandonment of the Fortuna-1 wells does not mean that other oil firms will not explore for oil elsewhere in Block 116, where other wells have been planned.

'The majority of the population is excluded from preventative and compensatory measures'

As for the impact study carried out by Maurel & Prom, this just took into account two Indian communities in close proximity to the oil drilling. It did not take into consideration the fact that around 73 other communities could also suffer consequences from chemical waste being released into the surrounding rivers.

The company headed by Jean-François Hénin took over the exploration rights for Block 116 in March 2009 from the company Hocol. This Colombian firm had itself acquired the permit in 2006 under the presidency of Peruvian head of state Alain Garcia, who had overseen the dividing up of the Amazon for Western multinationals. Hocol, which produced 15,000 barrels of oil a day, was already in Maurel & Prom's hands, though they then sold it in 2009 along with several exploration permits in Colombia for 748 million dollars to the Colombian national company Ecopetrol.

An inquiry by Colombia's financial watchdog the Contraloría General de la República de Colombia meanwhile revealed in 2013 that the French firm had stipulated as a “condition” of the sale the purchase by Ecopetrol of several shell companies based in the Cayman Islands – Hocol Petroleum, Homcol Cayman and Hocol SA (Islas Caimán).

At the end of September 2015 CCFD-Terre Solidaire published a report (see here) on the “impact” in Peru of the oil operations of Maurel & Prom and another French firm, Perenco, which operates further to the east in the Amazon. “The failures of Perenco and Maurel & Prom in the identification and the management of risks in Blocks 67 and 116 lead one to ask questions over their share of the responsibility in the pollution of the water and the soil that has been noticed in those lands,” wrote the NGO. “In its environmental impact study Maurel & Prom minimise the risks linked to the usage of toxic products and planned to spread dangerous waste on the Awajún peoples' land.”

Maurel & Prom, who declined to respond to Mediapart's questions, criticised what it called the “undoubted exploitation” of the CCFD report “which in reality relates to a much larger and more fundamental contentious issue, which is the debate concerning the Amazonian land over which the native communities and the Peruvian state are in dispute.” The company added: “What is at the centre of the report in reality is the appropriateness of authorising or not any process of exploitation of these communities' lands.” In fact, since June 2007 some 87 Indian leaders, representing 55 communities, have proclaimed their “rejection” of exploration and production operations on their lands. Maurel & Prom had initially planned to build four wells at two drilling platforms, including one in the middle of a natural park.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

“The affected areas of the oil projects have been defined very tightly, excluding many lands and communities that could nonetheless be impacted by the activities of Maurel & Prom,” said the CCFD in the report. “The majority of the population is excluded from preventative and compensatory measures, as well as the participative measures planned by the companies.”

Both French and Peruvian NGOs have examined the impact study produced by the French oil company. The chemical products that Maurel & Prom indicated they would use in the drilling fluid turn out to be “corrosive, inflammable and toxic”, carcinogenic and dangerous to wildlife. “The inadequacy of the risk management plans put forward by the company leads one to fear major impacts on the health of the workers brought in to handle the toxic residue and on the surrounding communities,” the CCFD report said.

The French company was also authorised to release waste water into streams. Its own impact study revealed that some 54,000 litres would be pumped out every day. But the locations earmarked to test the quality of the waste water were four to 33 kilometres from the drilling rig and neither upstream or downstream of the water being pumped out, noted the CCFD. “This irregularity leads one to question the reliability of the results given by the company,” it added. In any case the location of these test sites means that they give no indications as to any possible contamination of drinking water used by communities who are closest to the drilling. Several senior figures in these communities have reported seeing dead fish in the rivers close to the pipes releasing water from the drilling site. The head of the nearby Kuit community has spoken of “muddy and bad-smelling waste”.

The CCFD also refer to “risky management” of the waste from the drilling, owing to the heavy metals – arsenic, mercury and lead – that it contains. The company's impact study envisaged extracting “23 tonnes of dangerous residue” during the well drilling, and transporting it to the base camp. It also planned to spread on surrounding land – using the technique of so-called 'landfarming' – some 10,601 barrels or 1,685,558 litres of waste material. “This technique diminishes the concentrations of hydrocarbons and oils, but it is ineffective in the reduction of concentrations of heavy metals,” the Peruvian NGO CAAAP said in a study. The French NGO CCFD, meanwhile, concluded: “Failures in the matter of waste management leaves one to fear major environmental impact on the soil and, through water flow and seepage, on water resources, with consequences for health and for the population's means of subsistence.”

The CCFD believes that the French state has “been lacking in its obligation to supervise its companies in Peru” in order to ensure that they respect human rights and the environment, and has “not put in operation the appropriate actions” in respect of them. Marie-Laure Guislain, of the ONG Sherpa, meanwhile says: “Sherpa also criticises the current abandoned state of the drilling rig, the anomalies in the impact study and the pollution criticised by the communities.”

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Sherpa has become an expert in the defence of victims of economic crimes and highlighting the responsibilities of companies, and in common with the CCFD has for some months been trying to help Peruvian organisations in the Amazon. “We hope that the Peruvian decision of January 19th will find in favour of the communities over the procedure for prior consultation,” says Marie-Laure Guislain, who is head of disputes in Sherpa's globalisation and human rights programme. “That would be a first step towards redressing the harms suffered.”

In March 2013 an Amazonian leader, Edwin Montenegro, president of the regional organisation representing the indigenous people of the north Amazon in Peru, ORPIAN-P, questioned the then French development minister Pascal Canfin about Maurel & Prom's operations during the World Social Forum held in Tunis. In November 2015 two senior figures from Peruvian NGOs, José de Echave from the organisation Cooperaccion and Adda Chuecas from CAAAP, came to Paris to plead the cause of the Amazon people at the COP 21 climate conference.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter