The timing is curious. The last four French hostages of a group kidnapped by Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) at a uranium mine (1) in Arlit, northern Niger, were released on October 28th, 2013 against a ransom of at least 30 million euros. Just four days later, two journalists with public broadcaster Radio France International (RFI), Ghislaine Dupont and Claude Verlon, were abducted and murdered in Kidal in northern Mali, an area where Tuareg separatists, jihadists and other militias have been active over several years.

Officially the two events are not related, or so the journalists' families have always been told by advisers to French president François Hollande and his defence minister Jean-Yves Le Drian. But a painstakingly-researched documentary broadcast recently on public TV channel France 2's investigative programme Envoyé Spécial has cast serious doubt on those assertions.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

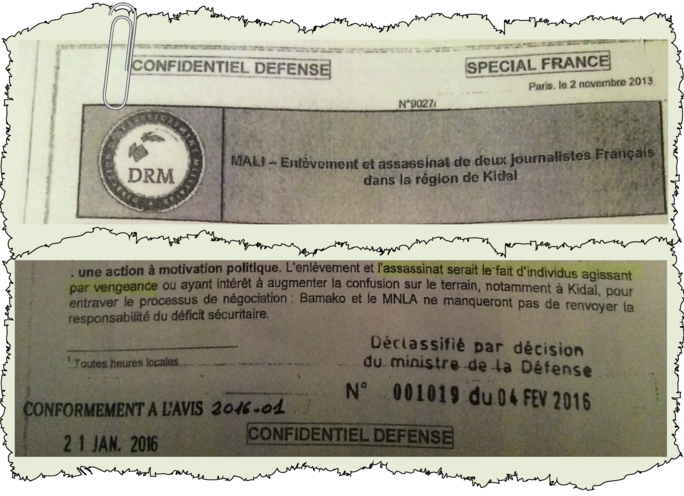

The programme's journalists, Geoffrey Livolsi and Michel Despratx, assembled witness testimonies as well as confidential briefing papers from France's Department of Military Intelligence - Direction du Renseignement Militaire (DRM) - which they made available to Mediapart. These documents support the theory of a link between the journalists' murder and the liberation of the Arlit hostages. One DRM brief refers to a possible motive of revenge on the part of AQIM, perhaps related to claims that part of the French government's ransom to free the Arlit hostages went missing.

Dupont and Verlon were themselves investigating rumours about ransoms, a highly sensitive subject because the French government officially denies that it pays them. The RFI journalists took off for Mali on October 25th, 2013 primarily to research a programme on the crisis and reconciliation in the north of the country after a French military push against AQIM earlier in the year. But they were also discreetly looking into the background to the Arlit hostages – three of the original seven hostages had been set free in 2011 - and had begun to do so even before they travelled to Mali.

According to Cheick Amadou Diouara, a Malian journalist who was one of the very few people in whom Dupont had confided, she had “wanted to understand how the chain of negotiations was structured […] and who was really paid”. Apparently this line of enquiry created waves. A person close to Dupont's family gave the computer she had left in Paris to the France 2 team, who passed it to an expert to investigate its contents.

Analysis of the computer showed it had been hacked from September 25th, 2013. A Trojan horse malware programme had allowed a hacker to spy on Dupont via the computer's camera and microphone and to see her files (see video extract above). Even more disturbing is that on November 2nd at 1.30 pm, half an hour before the two reporters were abducted, the hacker accessed Dupont's computer and deleted all her emails.

At that precise moment Dupont and Verlon were interviewing a leader of the Azawad National Liberation Movement (MNLA), the Tuareg separatist movement in northern Mali. As they left the meeting the RFI pair were kidnapped by four men, who sped off with them into the desert in a sand-coloured pick-up truck. According to a DRM brief, the vehicle broke down 12 kilometres north of Kidal, which “probably precipitated their decision to execute” the journalists. French soldiers who had been dispatched after the kidnappers found the journalists' bullet-riddled bodies.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

In a brief labelled 'Confidential - Defence' dated November 2nd, 2013, the day of the abduction, the DRM listed three hypotheses, one of which specifically mentioned “individuals acting out of revenge” (see document above). French army spies also identified the person who ordered the operation as one Abdelkrim le Touareg, chief of AQIM's Al-Ansar brigade, which claimed responsibility for the kidnapping.

The French military intervention in Mali, Operation Serval, had killed Abou Zeid, head of AQIM, earlier in 2013, and since then Abdelkrim had taken over the guarding of the French hostages. A negotiator from Niger, acting with support from Niger's president Mahamadou Issoufou and the country's defence minister, had dealt with Abdelkrim over the release of the Arlit hostages from the summer of 2013. Niger had taken over handling hostage negotiations from the team put in place by the French external intelligence agency, the DGSE.

At the time Abdelkrim, who was subsequently killed by the French army in 2015, claimed responsibility in the following terms: “The assassination of the journalists is the minimum price that President François Hollande and his people should pay.” This is strange wording given that France had just paid out millions in ransom for the Arlit hostages.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

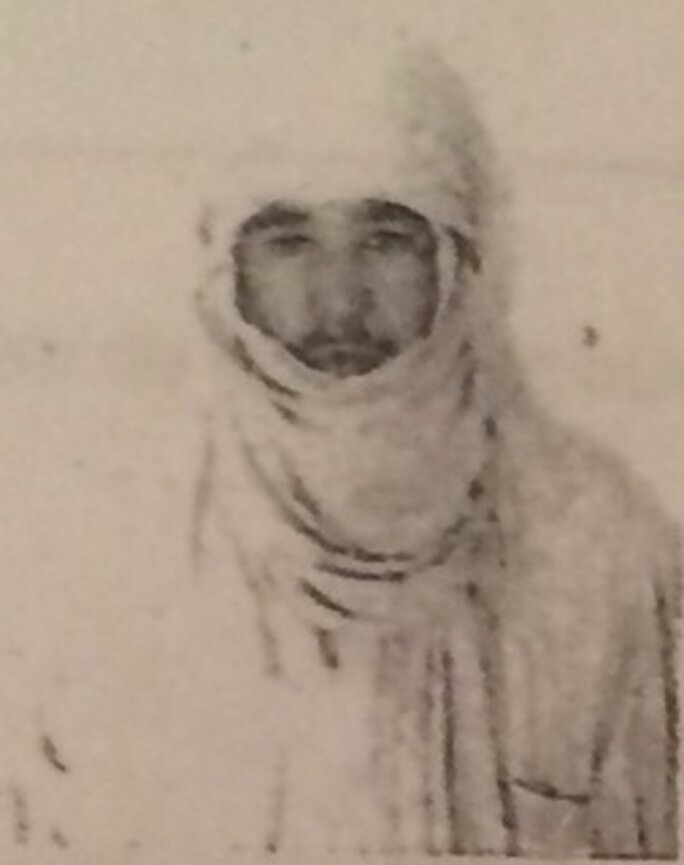

Military intelligence quickly identified the four who had kidnapped the RFI journalists. Two are members of Al-Ansar, including the owner of the vehicle who headed the commando, Baye ag-Bakabo. According to the DRM, he was known to be close to Abdelkrim and had “heatedly complained […] of never having received sums of money to thank him for his help in taking on the guard” of the Arlit hostages (see document above).

Did Baye ag-Bakabo and the men of Al-Ansar brigade abduct, then murder, the journalists as revenge for not having received their part of the ransom? At this stage that remains purely a hypothesis. In any case, suspicions of this possibility reached the ears of Alain Juillet, a former DGSE operative who has remained close to the North Mali Tuaregs.

“Certain rumours circulated in North Mali saying that the sum that was handed over […] was incomplete,” Juillet told Envoyé Spécial. “There was money missing. How much? I don't know, but it seems money was missing and that made one of Abou Zeid's lieutenants furious.” According to Juillet's sources, the lieutenant in question was Abdelkrim, the AQMI leader who claimed responsibility for the journalists' abduction (see video above).

If part of the ransom was indeed syphoned off, it still needs to be established by whom. “That's the central question,” Juillet continued. “Was it taken before, was it taken at the site and was that what made Abdelkrim furious? The ransom was then shared between the various groups of AQIM fighters. So once they had failed to obtain what they expected, they were unhappy.”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

1. The uranium mine in Arlit, northern Niger, is owned by French nuclear power company Areva. The hostages were Areva employees.

Wall of defence secrecy

There are other indications, too, that not all the promised money was handed over. The French Defence Ministry had given Pierre-Antoine Lorenzi, a former DGSE operative who at the time was CEO of a security firm, Amarante, the task of being the go-between between France and the Niger negotiator in the talks over freeing the Arlit hostages. Lorenzi says that DGSE boss Bernard Bajolet did not pay a sum of three million euros that was due - over and above the ransom - for paying the ground team that had allowed the hostages to be freed. “That means that a certain number of commitments I made in the name of France were not met,” Lorenzi told Mediapart.

And in that ground team there were individuals with links to AQIM. Could they have taken revenge by kidnapping the journalists? Lorenzi himself is convinced they did not, saying: “The team that was built, we control it, it is a team of trust.” And, he said, at the time Dupont and Verlon were killed, “I was not told that the commitments had not been met”.

In fact, the ground team would only learn that they would not be receiving payment “eight months, ten months, practically a year” later, Lorenzi said. However, a DGSE official told Mediapart that Lorenzi did not play a role in the negotiations, and there had never been any question of paying the three million euros.

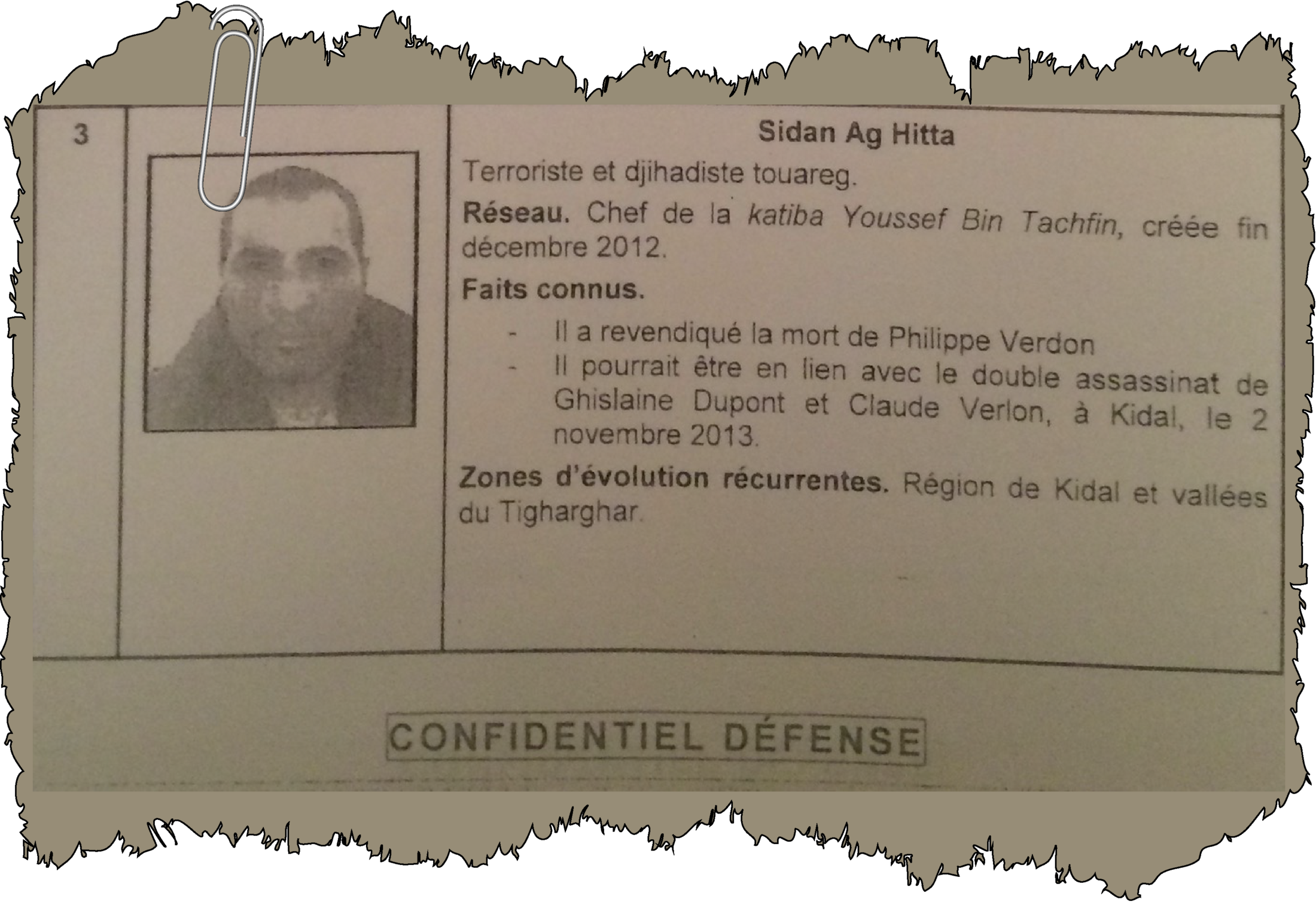

Money is not the only possible motive for the assassination. Several confidential DRM briefs said members of the commando that abducted the journalists were close to Sidan ag-Hitta, an AQIM chief. A DGSE brief stamped 'Confidential - Defence' suggests he “may have been linked to the double murder of Ghislaine Dupont and Claude Verlon” (see document below).

Enlargement : Illustration 8

Speaking to Envoyé Spécial, whose programme was broadcast on January 26th, Ikinane ag-Attaher, an official for the Tuareg movement MNLA, confirmed that this connection identified by French army spies was indeed a possibility. The journalists were abducted, he said, because two nephews of Sidan ag-Hitta, who had kidnapped Frenchmen Serge Lazarevic and Philippe Vernon and were imprisoned in Bamako at the time, “had not been freed as part of the negotiation” over the Arlit hostages.

One of the nephews, Mohamed Ali ag-Wadossene, was mentioned in a DRM brief dated July 6th, 2015, after he was “neutralised” by French forces. He had been freed when Lazarevic was released on December 9th, 2014.

One thing is certain: the person behind the kidnapping and several members of the commando that murdered the journalists had been involved in guarding the Arlit hostages. Yet the highest echelons of the French government have always refused to make the slightest connection between the assassination and the circumstances under which the Arlit hostages were freed.

In March 2016, and with the utmost secrecy, defence minister Le Drian and his chief of staff, Cédric Lewandowski, attended a meeting of the Association of Friends of Ghislaine Dupont and Claude Verlon, according to the association's spokesman, Pierre-Yves Schneider. He told Envoyé Spécial: “I remember asking [Le Drian] a question at the end of his speech. I asked him if he made any link with the Arlit hostages. And he replied no, there was no link.”

The DGSE official told Mediapart that “no material element allows [us] to make a link between the two abductions, at Arlit and the one that led to the deaths of the RFI journalists. It is better to remain extremely cautious and not give in to fantasies.”

Why do the authorities deny so categorically a line of enquiry that is mentioned in black and white in French military intelligence briefs? That is the question friends of the two journalists are asking. On January 13th, the Association of Friends of Ghislaine Dupont and Claude Verlon, Reporters Sans Frontières (Journalists Without Borders) and RFI journalists organised a demonstration outside the Palais de Justice in Paris to denounce “the government's silence”, saying the French authorities appeared to have no desire to see justice done.

The legal investigation, at first headed by anti-terrorist judge Marc Trévidic and then by his colleague, Jean-Marc Herbaut, is indeed progressing very slowly. The examining magistrate has not yet been to Mali and not a single witness has been heard. The judges have also hit a wall of defence secrecy. The Defence Ministry has declassified about 100 confidential documents, particularly from the DRM and the DGSE, but many of these have been blacked out and 75 more remain secret.

“So the use of these documents by the judge is turning out to be extremely difficult and partial,” said Schneider, the association's spokesman. “Why does the Army appear to want to hide something? That is the question we have asked since the outset and that we continue to ask.”

The investigation for the documentary itself also proved extremely difficult. Both the Elysée and the Defence Ministry were silent. While the journalists for Envoyé Spécial were in Kidal, the United Nations force there agreed to give them protection in the town. But they were forbidden to leave the camp following pressure from the French foreign ministry, officially because the risk of abduction was too high.

Several witnesses they were due to interview changed their minds after receiving threats. “There is someone watching you in everything that you do. You have a flashing light on your head […] they will follow your every move,” one of these witnesses, who asked not to be named, told them.

This is a curious echo of the hacking of Dupont's computer three years earlier. It is as if someone wanted to smother the story of the release of the Arlit hostages and the murder of the two RFI journalists under the same blanket. Both are affairs of state whose secrets will be very hard for the justice system to lay bare.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Sue Landau