Argentine international players and Paris Saint-Germain stars Angel Di Maria, nicknamed “the noodle” (El Fideo) and Javier Pastore, aka “the thin one” (El Flaco), have even more in common than meets the public eye. Documents from Football Leaks, obtained by German weekly Der Spiegel and analysed by the journalistic collective European Investigative Collaborations (EIC), reveal that both players share a close interest in tax havens.

Pastore and Di Maria are both linked to a secretive group of Argentine agents which controls the careers of numerous South American football stars, including Monaco’s Colombian striker Radamael Falcao, Real Madrid midfielder James Rodriguez, who captains the Colombian national team, and Argentine striker Gonzalo Higuaín (who was recently bought by Juventus for 94 million euros).

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Behind at least 60 players is an informal cooperative made up of five argentine agents, who siphon off money from image rights and transfer deals into offshore structures via companies administered by frontmen in the Netherlands.

What might be called an ‘Argentine connection’ in the international football business includes incidents of match-rigging and arranging the selection of players in their national team in order to boost their transfer market value.

Di Maria’s earnings from image rights transit through a Panama-registered company called Sunpex.

Meanwhile, between 2013 and 2015, Pastore received a total of 1.9 million euros from sportswear company Nike via a shell company in Uruguay – a country also known as "the Switzerland of South America".

On December 7th, the Madrid public prosecutor’s office, acting on information from the Spanish tax authorities, launched an investigation into the financial affairs of Di Maria and two other former Real Madrid players, Xabi Alonso and Ricardo Carvalho.

Both Angel Di Maria and Javier Pastore declined to answer questions from the EIC. Di Maria’s longstanding agent, Eugenio Lopez, did not respond to our attempts to interview him.

On the basis of his accumulated transfer fees, Di Maria is the most expensive player in the history of football. A total of about 180 million euros have been spent in his moves between clubs, beginning with his transfer from Argentine side Rosario to Benfica in Portugal, to Spanish club Real Madrid, then to English side Manchester United, and now to French club Paris Saint-Germain (PSG).

In line with all top-ranking players, he receives payments from the sales of his image rights for commercial use. These are on top of his salary, which at PSG currently amounts to a gross sum of more than 1 million euros per month (excluding bonuses).

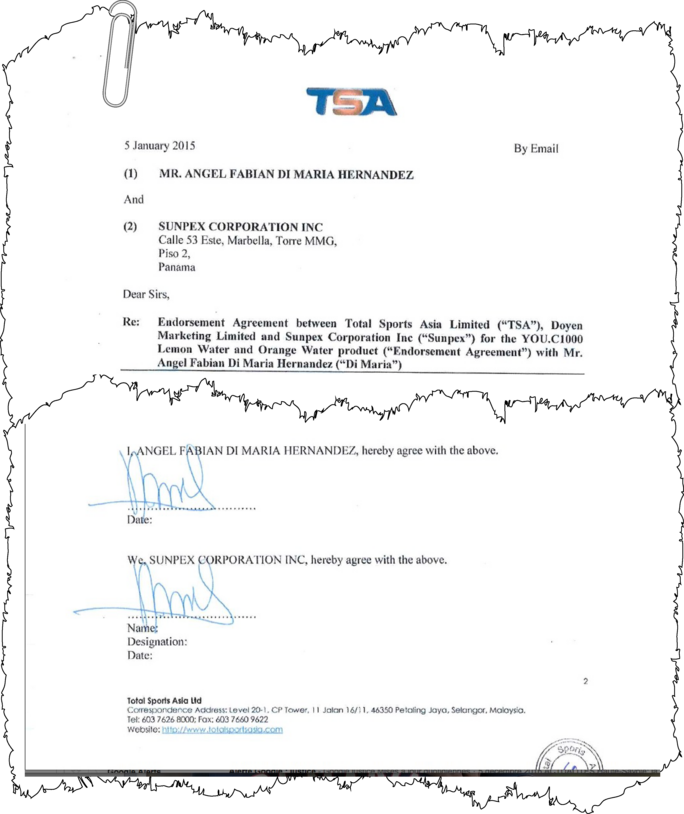

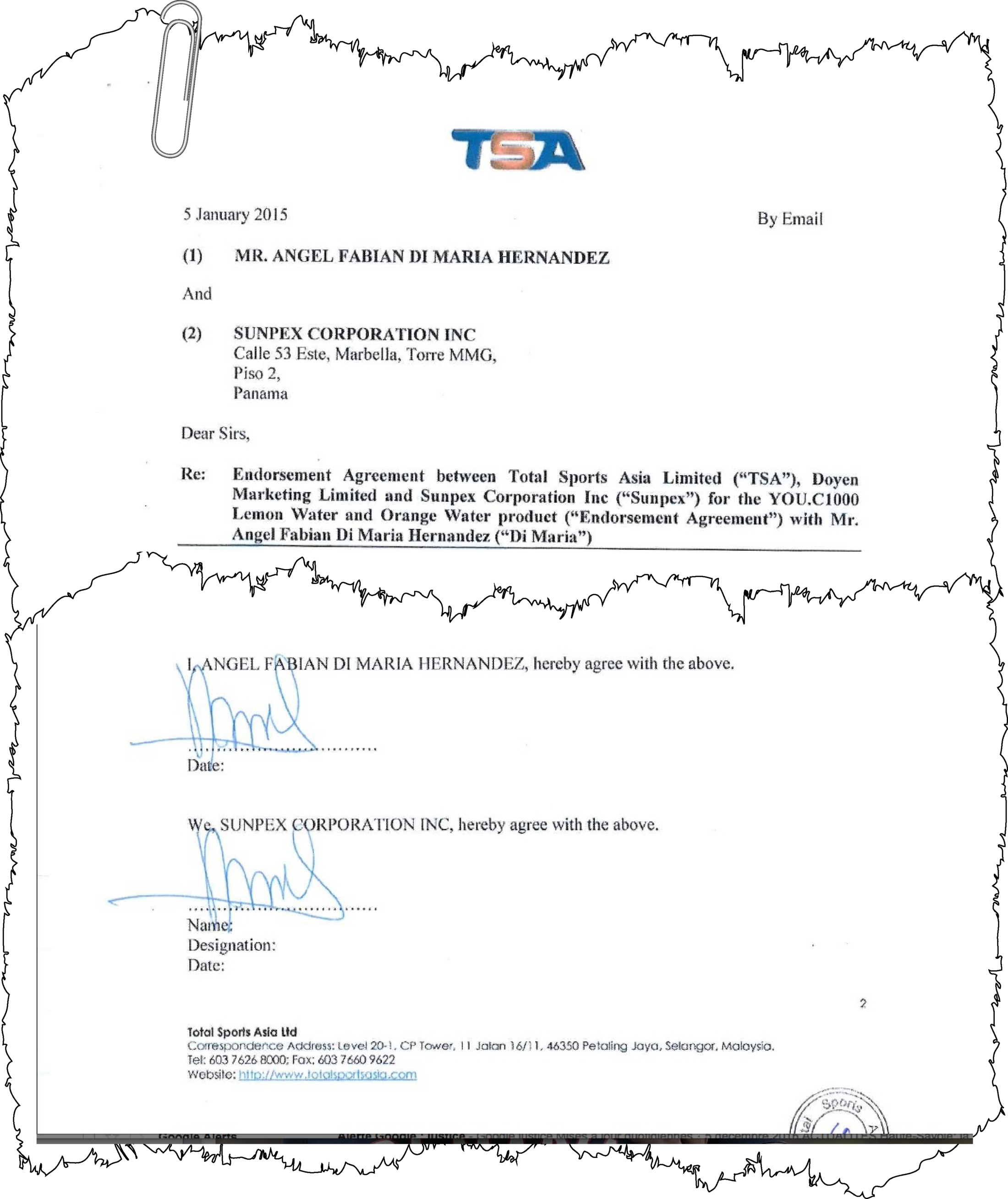

In the autumn of 2014, a company called TSA, which markets a high-energy drink in Asia, had attempted in vain to engage David Beckham to advertise its product. Beckham’s fees were too high for the firm, and TSA then turned to Doyen Sports Investment, which managed Beckham’s image, to ask if he might help in approaching Di Maria, who was then with Beckham’s former club, Manchester United.

The 150,000-euro fee offered by TSA was in return for five hours of shooting videos and stills, after hair-styling and make-up, the sending out of a marketing message in his name on social media, and the signing of 30 autographs of football shirts. Di Maria accepted the deal.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Usually, it would be Gestifute, the company run by agent Jorge Mendes, who manages Di Mari’s image rights. But given the involvement of Doyen Sports it was authorized to conclude the contract.

Gestifute told Doyen Sports that Di Maria wanted the fee to be paid into his company Sunpex, registered in Panama, a tax haven, and created in 2009. Doyen sent an email to TSA, in which it explained: “Di Maria does not want a reference to his name in the contract. He wants only Sunpex as the name of the contracting party. I am sure you know that it is very common for sportsmen to place all their image rights within a company.”

Doyen Sports was subsequently more specific. “Di Maria does not want his name to appear for tax reasons,” it explained. To reassure the sponsor, both Sunpex and Di Maria sent a written pledge that the player would fulfil his contractual requirements. Di Maria signed both for himself and for Sunpex.

According to Forbes magazine, Di Maria is one of the highest-paid football players in the world. In 2015 alone, he earned 2 million dollars in image rights payments, of which a large part came from Adidas. Questioned as to whether the payment by sportswear firm was made via Sunpex, Adidas replied that the contents of contracts were by principle “confidential”.

Pastore arrived at French club PSG in 2011. In 2009, when Pastore left Argentine side Huracán for Italian club Palermo, his agent, Marcelo Simonian, was acting both as the agent and part-owner of the player, in which he held a 50% stake of economic rights, and also as an agent for Palermo. The Italian football federation handed the chairman of the club a 12-month suspension from his activities for allowing the conflict of interest. The role of Simonian in the deal was reportedly to be investigated by world football governing body Fifa, but the agent says he has still not been contacted about the case by the Italian federation.

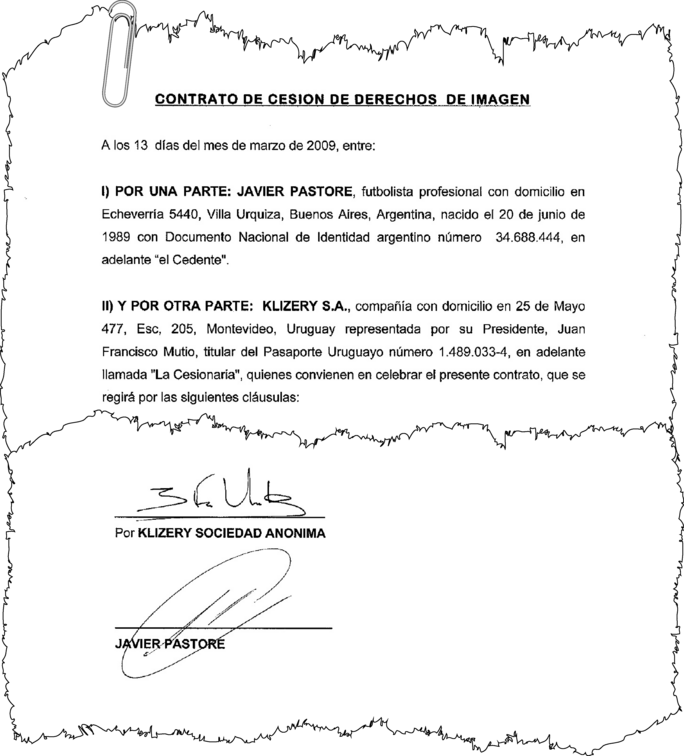

In March 2009, one month after the deal with Palermo, Pastore sold his worldwide image rights up until 2020 to a company registered in Uruguay, Klizery SA, for the sum of 50,000 dollars. The amount was surprisingly low and for good reason: the Uruguayan company is one of the shell companies used by the Argentine agents as a vehicle for money transfers.

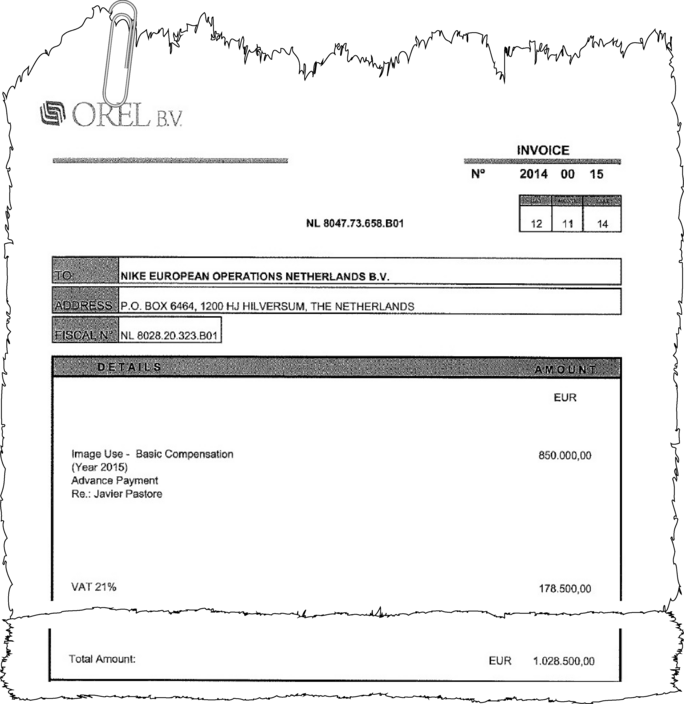

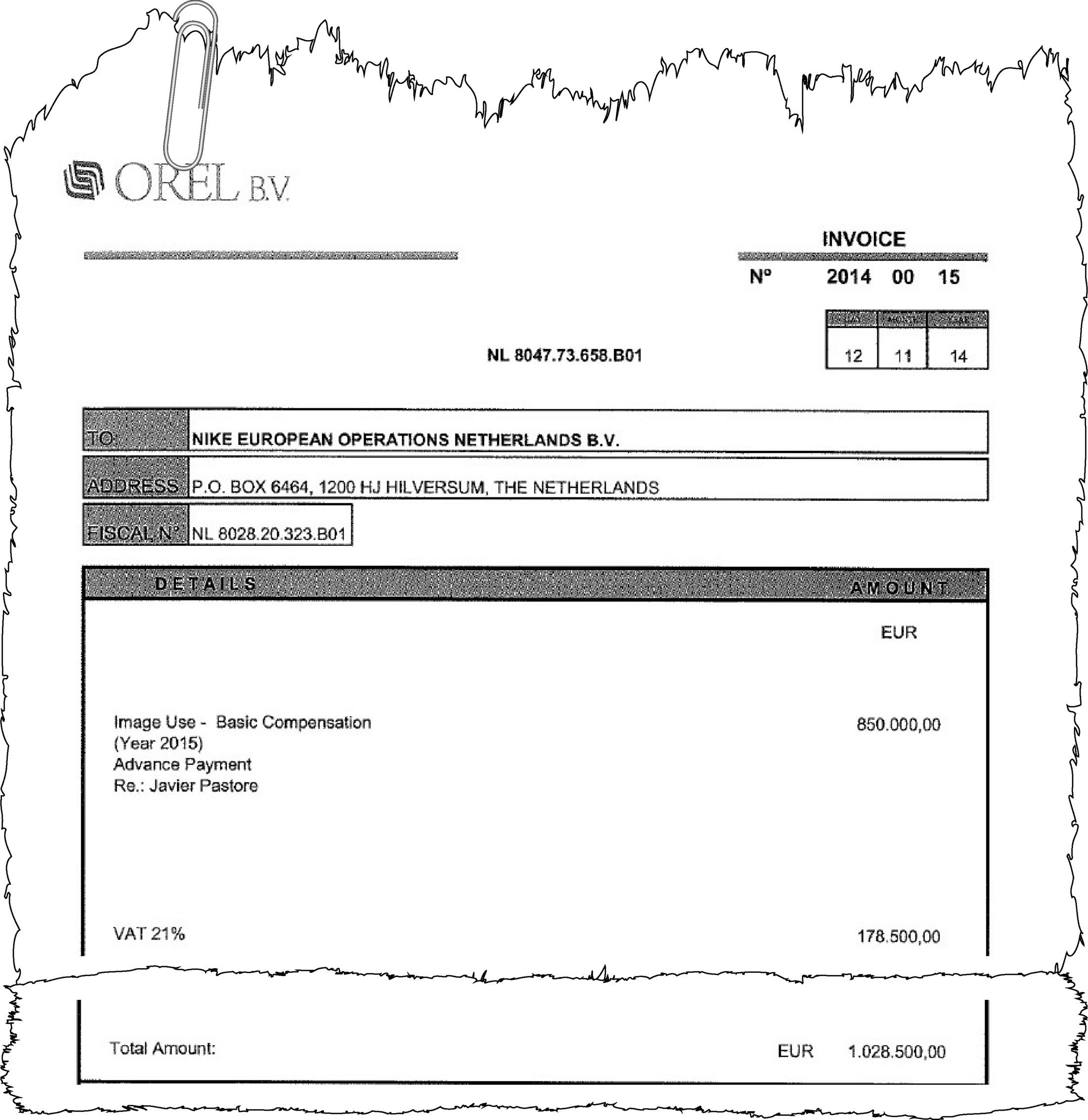

Enlargement : Illustration 4

On July 10th 2010, a new contract was signed between Pastore, Klizery and the Dutch company Orel, which was given the mandate for commercializing Pastore’s image rights. The Netherlands offers an advantageous company tax rate, and trust companies in the country offer ‘off-the-peg’ shell structures administered by managers who act as frontmen for the true owners. Their role is very similar to that of companies in Ireland involved in the tax haven structure set up for Portuguese star Cristiano Ronaldo, previously revealed in our investigation here.

The system means that clubs and commercial companies do not pay for the use of image rights directly into a company registered in a tax haven, but instead into what appears as a more respectable company address in the Netherlands.

In the case of Pastore, and as of 2010, Orel transferred 94% of the value of the deals it struck into the Uruguayn shell company Klizery. Parallel to this, Pastore signed a five-year contract with Nike, which was to end in 2015. A total of 1.915 million euros before VAT (2.3 million euros including VAT) were paid by Nike, arriving first in Orel before then being transferred on to Klizery.

Pastore’s transfer in 2011 from Palermo to PSG cost 43 million euros with bonus payments, a record fee for French football – as was also his salary, at 350,000 euros per month. The deal earned Simonian 15 million euros from the sale of his stake in the player’s economic rights.

In 2014, after a successful initial period at PSG, Pastore extended his contract with the club until 2019. Simonian did not have a licence to operate in France and therefore called on the services of Laurent Gutsmuth, a French agent who signed the contract and who was paid a commission for his services. The practice is perfectly legal, but it is a questionable one if Gutsmuth acted solely as a frontman. In fact, Simonian was involved in the negotiations from start to finish. Gutsmuth was paid 1,010,000 million euros by PSG, of which he subsequently gave Simonian 1 million euros, keeping the remaining 10,000 euros.

Questioned about his role, and in justification of his commission, Gutsmuth insisted that “I also oversaw a legal section” of the contract. The French agent said he was “certain” that he did not pay the money due to Simonian via a Dutch company.

PSG, also questioned by the EIC about the deal, insisted it always declared the names of agents involved in such a contract, adding that “the distribution of the commission between the signing agents is subsequently left to their free assessment and the club is not required to know the detail of this or to question the foundation”. In other words, the club does not believe it should know where its payments finally end up.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Also in 2014, Pastore renegotiated his contract with Nike. By then, PSG had increased its ranking in Nike’s internal evaluation of clubs, which allowed Pastore to earn up to 850,000 euros per year on condition that he took part in more than 65% of PSG’s matches and in more than 60% of matches involving the Argentina national squad.

While Di Maria has his own company for the payment of image rights, Sunpex, Pastore is one of several players to use Klizery for such payments, including Argentine midfielders Ever Banega, who plays for Inter Milan, and Ricky Alvarez, who plays for Sampdoria.

Several players in France who are connected to the Argentine agents use other companies. Argentine winger Lucas Ocampos, currently on loan by Marseille to Italian Serie A side Genoa, was in 2015 paid 1.475 million euros via a Dutch company called ITB International, which transferred the money on to a company called Paros registered in the Caribbean tax haven of the British Virgin Islands. In a transaction concerning Argentine forward Emiliano Sala, who plays for Nantes, Paros billed Dutch company Northfields Sports BV for the sum of 23,310 euros.

Questioned by the EIC, Simonian insisted he was “100% clean” and that he declared all of his revenues to the tax authorities. He denied any link with striker Gonzalo Higuaín, who was transferred to Juventus this summer from Napoli for 94 million euros. He said his role for Colombian midfielder James Rodriguez, who plays for Real Madrid, was limited to that of a consultant. He said he had no business dealings concerning players Radamel Falcao (Monaco), Argentine players Ricardo Álvarez (Genoa) and Juan Pablo Carrizo (Inter Milan), and the Uruguayan Martin Cáceres (Juventus).

Portuguese club Porto confirmed to the EIC that Simonian uses Dutch shell companies, as is demonstrated in the Football Leaks documents. The companies are also used by at least four other Argentine agents, none of whom agreed to answer questions from the EIC. They are Eugenio Lopez (Di Maria’s agent), Hernan Berman, Jorge Prat-Gay (brother of Argentine economy minister Alfonso Prat-Gay, a former governor of the Argentine central bank), and Jorge Cyterszpiler.

After contracting polio and forced to abandon his early ambition of a career as a footballer, Cyterszpiler, then aged 16, found work as an agent after coming across the outstanding talent of Diego Maradona, who was two years his younger. Cyterszpiler was behind Maradonna’s signing with Argentinos Juniors, and he would later arrange the player’s transfer to his first European club, Barcelona. Cyterszpiler went on to partner business deals with Coca Cola and sportswear and accessories firm Puma.

After becoming involved in politics (in 1989 he led Carlos Menem’s successful campaign to become Argentina’s president), Cyterszpiler returned to his activities as a football agent. He eventually settled in the Netherlands, in the small town of Nieuw-Vennep, south-west of Amsterdam. Since 2010, he runs a company that has no staff, called Fruder Sport BV.

Among the catalogue of Dutch companies whose creation he oversaw, Amsterdam-registered Kunse was chosen to be involved in Di Maria’s most recent transfers. For beyond being used for channelling payments from image rights, the Dutch companies are also the vehicle for payments from transfer deals.

In Di Maria’s move in 2014 from Real Madrid to Manchester United, 2 million euros was sent by the English club to Kunse, arriving on the account on October 9th 2014. Of that sum, 1.85 million euros was redirected on November 14th 2014 to shell company Paros Limited in the British Virgin Islands. When Di Maria was transferred to PSG one year later, for a fee of 63 million euros, a similar process was used: it was the company belonging to Portuguese agent Jorge Mendes, GestiFute, which paid 50% of what it earned from the deal into Kunse.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

Questioned by the EIC, PSG confirmed the involvement of agents Jorge Mendes and Eugenio Lopez but said it was not aware of where the payments eventually transited. It said it had remunerated Mendes’s company Gestifute International “but does not have knowledge of the distribution of this remuneration between Gestifute and the other agents who intervened on behalf of the player”.

However, the issue of the payment chain was a problem for Spanish club Sevilla. In October 2014, a legal affairs director of the club alerted his senior management over the terms of a player’s transfer to Sevilla, organised by one of the group of Argentine agents. The legal affairs director had discovered that behind a Dutch company which was to receive a payment from the transfer deal, a second was involved, based in a tax haven. He warned of the potential problem with the Spanish tax authorities.

In a missive obtained by the Football Leaks platform and accessed by the EIC, the financial affairs director wrote to the Dutch company concerned, explaining that his club “does not feel at ease and cannot accept” that the Dutch company in turn transfers the payment “to a company based in a country without a tax treaty and without transparency”. The incident illustrated that clubs can, by examining the payment routes more closely, cut off the system.

While the connection between Gestifute and the clan of Argentine agents is striking regarding the deals surrounding Di Maria and Falcao, the agents use other means when the relationship with Jorge Mendes’s company is not enough to seal a deal. This was the case in the 2014 transfer of Di Maria from Real Madrid to Manchester United.

PSG had already made moves to bring the player to the French capital. In a conversation via mobile phone platform WhatsApp, the contents of which were accessed by the EIC from Football Leaks, his Argentine agent, Eugenio Lopez, spoke of how Di Maria had no wish to join the Paris club. The problem however was that a deal with Manchester United was uncertain, and so Lopez made contact with Nelio Lucas, the Portuguese head of London-based Doyen Sports, to ask him if he could convince the then manager of Manchester United, Louis Van Gaal, to sign Di Maria.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

Lopez made known that he had given Van Gaal the phone number of Alejandro Sabella, then the coach of the Argentine national team, with the aim that Sabella would convince Van Gaal of Di Maria’s skills.

From another conversation via WhatsApp two years earlier, it was clear that the relationship between Lopez and Sabella was a close one. On August 28th 2012, as the transfer market was coming to an end, Lopez spoke to Lucas to convince him he should invest in one of the agent’s players, Argentine striker Rogelio Funes Mori. During the conversation, Lopez repeated several times that he was the agent for Argentina coach Alejandro Sabella, advising Lucas that he was a longstanding friend of Sabella’s.

In another conversation with Lucas the following day, Lopez was more explicit: “Listen to me Nelio,” he said. “I’ll have him selected by my coach, and his value will rise. That’s what I did with Di Maria.” The first time Di Maria was chosen to play for the Argentine national team was in September 2008, before Sabella became the team coach. Nelio Lucas appeared to understand the matter, replying “I know, I have confidence in you”.

In the end, no deal was struck for Rogelio Funes Mori, but three weeks later he was selected as a substitute for the national team by Sabella in a friendly match against Brazil, when he came off the bench 14 minutes before the end of the game. It was to be the only time he played for the national team, but it was enough to be able to write on his CV that he was a member of the national squad, which he could hope had the effect of upping his market value.

There is no evidence that Sabella, who did not respond to our request for an interview, was paid for helping Lopez, nor that he spoke about Di Maria with Manchester United manager Louis Van Gaal. But Doyen Sports involvement appeared to have been fruitful because Di Maria joined United just a few days after Lopez and Lucas had spoken in August 2014. The transfer fee was 75 million euros. There were added bonuses included in the deal, whereby United would pay a further 10 million euros if Di Maria was awarded the prestigious Fifa Ballon d’Or title, and a punitive payback of 50 million euros if ever the following summer he was sold to Real Madrid’s arch rivals Barcelona. It was then the most expensive transfer deal in the history of the English Premier League.

Lopez, who is also head of the independent body that is responsible for the lottery halls and casinos in the Buenos-Aires region, claimed that Lucas had simply done him a favour. “We never spoke about a commission,” Lopez told Lucas.

It was not the first time Lopez found himself in a dispute over unpaid services. In February 2014 he was ordered by the Lausanne-based Court of Arbitration for Sport to pay 375,000 euros to Italian football agent Andrea D’Amico who Lopez had failed to remunerate for his part in Di Maria’s transfer in 2010 from Benfica to Real Madrid.

But were agents and players the only ones to benefit from the offshore payment system? The contents of emails exchanged on the encrypted web-based email service Hushmail suggests that others are hidden behind the clan of Argentine agents and Dutch companies.

Carlos Rivera is the joint owner of the Argentine financial company Grupo Alhec, and a former vice-president of the Argentine chamber of stockbrokers. The Football Leaks documents place him at the centre of all the financial structures, money transfers and billing in the agents’ dealings. He speaks of shell company Paros as “my company”.

In 2013, Alhec employees in Uruguay were found carrying bags containing 1.2 million euros in cash, apparently destined to be taken to Argentina. Alhec said the money was from the sale of Argentine players, and was destined for a Panama-registered company. The incident led the Uruguayan central bank to order the closure of Alhec’s subsidiary in Montevideo, citing “moneylaundering” of cash sums linked to football.

At the same time, and with no direct link to the events, an Argentine investigating magistrate launched a probe into a suspected vast system of moneylaundering allegedly linked to the club transfers of Argentine players in Europe. In June 2013, about 150 police raids were carried out targeting players, agents, the Argentine football federation and the country’s central bank. The investigation suspected that the undeclared sums placed in tax havens were brought to Argentina by the Chilean and Uruguayan subsidiaries of the Grupo Alhec.

The investigations involved well-known players, and notably another Argentine player who once wore the colours of PSG, Ezequiel Lavezzi, who now plays in China. Lavezzi, along with his brother Diego who acted as his representative, was formally suspected of “falsification of documents and moneylaundering the proceeds of tax evasion”.

Enlargement : Illustration 9

During the summer of 2013 panic set in among the principal protagonists. Alhec boss Carlos Rivera and his partner Kresimir Juan Bielic went into hiding (they later wound down Alhec and created a new company called Pro Accion). Up until then, the payments made via the Netherlands were carried out with little attempts at dissimulation, but the Argentine investigation was to change that, and Alhec then used instead Uruguayan company BGL Asesores.

It was just several weeks after the police raids in June 2013 that Paros was created in the British Virgin Islands, into which most of the money from the sales of Argentine players was sent. Carlos Rivera, staff at BGL Asesores and the football agents began sending emails to each other only via the encrypted web-based email service Hushmail, using aliases, abbreviations, and numbers, such as the alias used by Rivera, “dj9548”.

Meanwhile, the Argentine judicial investigation was to end in failure after prosecutors refused to envisage a trial, arguing that the magistrate in charge had not found sufficient evidence. He was removed from the case.

But the results of phone taps ordered by Oyarbide were compelling, as revealed by Argentine television in a report broadcast in June 2015. It revealed that one of the tapped conversations, held in June 2013, demonstrated the very close links between Argentine internal trade secretary Guillermo Moreno and Carlos Rivera, who had been placed under investigation and who was then on the run. Moreno told Rivera: “It must not get to you, and that depends on you. If you need something, you call me.” Moreno called Rivera “my baby”. It was just several weeks after that conversation that the investigation was shelved.

The transcript of another phone tapping operation gave an indication of what the moneylaundering could be used for. Carlos Rivera is a keen supporter of Argentine club Independiete. In order for it to remain in the country’s first division, the Primera División, it was vital that club Colón de Santa Fé won an upcoming match against Argentinos Juniors. Rivera put in a call to his friend Jorge Cyterszpiler to discuss motivating the players of Colón de Santa Fé. The conversation went as follows:

Cyterszpiler – “You remember that last time they said they received very little money […] So the question to put to them is how much they want for a 0-0 and how much for winning.”

Carlos Rivera – “That’s it, it’s exactly that.”

Cyterszpiler – “So the question is asked like that?”

Carlos Rivera – “Yes, yes. Perfect.”

The next day, Rivera asked Cyterszpiler about targeting Colón’s No 9, Emmanuel Gigliotti. Cyterszpiler told him: “That’s already done. It’s my present, that […] I told him I’ll give him a present for each goal.” Rivera replied: “OK. But ask him also for the rest of the team.”

The day after that, according to information given to the EIC, Rivera spoke with the president of the Colón de Santa Fé team, German Lerche, a former secretary-general of the Argentine national team selection board, who said he would send mobile phone text messages to all of the team to help with the plan.

Contacted by the EIC, German Lerche denied any involvement and said he had never used money to motivate a player.

While the Argentine investigation was surprisingly shelved in 2013, the Uruguayan central bank, in February 2015, banned Rivera and the head of Grupo Alhec’s subsidiary in Uruguay from exercising financial activities in the country for a ten-year period.

Subsequently, the Argentine investigation into the suspected scams was reopened, headed by a new examining magistrate whose mission is to establish the precise financial mechanisms of the alleged moneylaundering.

The EIC contacted Simonian by phone during a recent visit he made to London. Asked about the use of Dutch companies, he said he had “never heard about them”. On the subject of Rivera, he said that he was “a banker with a long and excellent reputation, who works with all the agents and all the clubs” adding: “I am his client […] sometimes I buy him shares, I carry out investments through him, he is not my principal banker”.

“I only lie to my wife,” Simonian joked, insisting that he paid his taxes in full, to the point, he claimed, that he was “the biggest tax payer in the Argentine football industry”. The joking continued when he asked whether the EIC was paying for the phone call – adding “I’m very poor because I pay all these taxes”. He finished the conversation with more humour: “I must leave you now because I have to give lots of money to someone.”

-------------------------

- Mediapart's report in French, on which this article is based, can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse