Former Libyan diplomat Moftah Missouri served as an interpreter and an advisor for the late Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi, who he began working directly for in the mid-1990s after 20 years as a career diplomat, and was privy to numerous confidential conversations between the Libyan leader and foreign leaders and officials, and notably Nicolas Sarkozy before and after the latter became French president.

Following the fall of the Gaddafi regime in 2011, Missouri fled to Tunisia, where he now lives in exile, and where Mediapart interviewed him earlier this month.

Missouri is a key witness in the ongoing French judicial investigation into Gaddafi’s suspected financing of Nicolas Sarkozy’s successful 2007 presidential election campaign, for which the former French president was in March placed under formal investigation for “corruption”, “illicit funding of an electoral campaign”, and “receiving and embezzling public funds” from Libya.

Evidence of the illicit funding of Sarkozy’s campaign by the Gaddafi regime was first disclosed by Mediapart in 2011, and among the numerous revelations it has published since was that, in April 2012, of an official Libyan document approving the financing.

Sarkozy has denied any wrongdoing.

Moftah Missouri began his career as a Libyan diplomat in 1975, following university studies in Paris, and occupied various posts abroad before becoming a senior official at the ‘France’ section of the Libyan foreign ministry’s European affairs department in 1988. He subsequently spent six years detached to the Libyan embassy in Paris, until he was appointed as Gaddafi’s personal interpreter and advisor in 1996.

As Mediapart has previously reported in detail, the first contacts between Sarkozy and his closest aides with the Gaddafi regime began well before the 2007 campaign, when Sarkozy, then interior minister, was preparing his bid to run as the conservative candidate to succeed then incumbent president – his political rival – Jacques Chirac.

Moftah Missouri was present when Sarkozy first met Gaddafi on October 6th 2005, in Tripoli, when Missouri acted as interpreter for the two men. The meeting was the result of intense lobbying for favour from the Gaddafi regime by Sarkozy’s close political team, notably led by his long-serving chief of staff Claude Guéant and longstanding friend, conservative politician Brice Hortefeux, assisted by the key intermediary in their dealings with Arab countries, the Paris-based French-Lebanese businessman Ziad Takieddine.

In the interview below, Missouri reveals for the first time that Gaddafi and Sarkozy secretly discussed the case of the Libyan dictator’s brother-in-law, Abdullah Senussi, the notorious head of the regime’s military intelligence services, who in 1999 was handed a sentence of life imprisonment in absentia by a Paris court for his role organising the bombing of a French passenger plane over Niger in 1989 that killed all 170 people onboard. Following the sentence, Senussi was the subject of an international arrest warrant issued by France, and Gaddafi sought to have the warrant withdrawn.

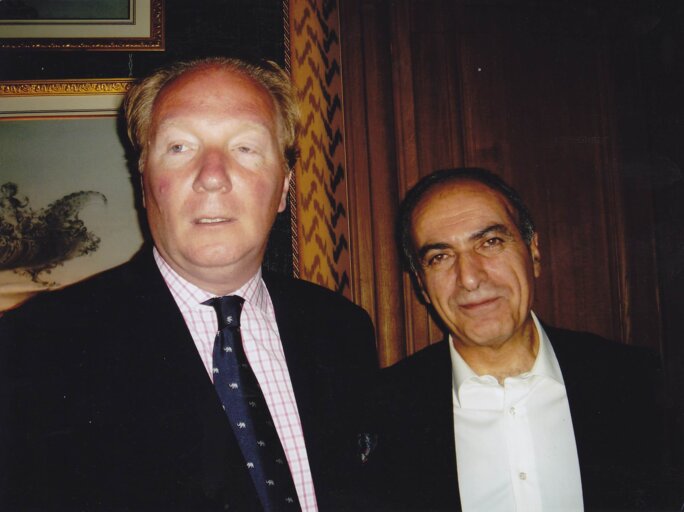

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Missouri also told Mediapart how Sarkozy subsequently announced to the Libyan leader that he had decided he would run in the 2007 presidential elections, and how Gaddafi immediately promised to “back” and “support” him, which Missouri affirmed meant financial aid. Also present at the meeting was an official French foreign affairs ministry interpreter who, under questioning in the current French judicial investigation, has twice refused to detail the contents of the conversation, citing her professional oath of secrecy.

He recalled the presence on the sidelines of that meeting of Guéant and Takieddine. Both have now also been placed under formal investigation in the current French probe into the suspected illegal funding, to which Takieddine has given testimony admitting he personally carried cash payments in briefcases from Tripoli which he delivered to both Sarkozy and Guéant.

During the interview, Missouri reiterated his confirmation of the authenticity of the official Libyan regime document authorising the funding of Sarkozy’s campaign, published by Mediapart in 2012, which he said he personally saw in Gaddafi’s office. He also said the sum of 50 million euros set aside in the document for the financing was subsequently reduced by the dictator, who Missouri often refers to by the dictator's self-proclaimed title of "the Guide", to 20 million dollars “although that could be an amount in euros”. Gaddafi, he said, confirmed the sum to him in person.

He also provided more detail on the still uncertain role of Sarkozy’s former wife, Cécilia, in the freeing, shortly after Sarkozy’s election, of five Bulgarian nurses and a Palestinian doctor who the Gaddafi regime had sentenced to death, later commuted to life imprisonment, for allegedly infecting 426 children with HIV while working at a hospital in the city of Benghazi.

Missouri has been contacted by phone to the ongoing French judicial investigation, but has not been formally questioned before the magistrates leading the probe. During his meeting on April 5th with Mediapart’s Karl Laske, whose interview with Missouri follows immediately below, Missouri said he was ready and willing to be questioned by the French magistrates.

-------------------------

Mediapart: You are one of the witnesses of the first meeting between Nicolas Sarkozy and Muammar Gaddafi, on October 6th 2005. How did this visit unfold?

Moftah Missouri: Nicolas Sarkozy did not stay for long. He was due to see his homologue, the Libyan interior minister Nasr al-Mabrouk but, as a sign of politeness, he was offered a meeting with the Guide of the Revolution. When he came, we sat under the tent. There were several people with him, but I saw Ziad Takieddine and Claude Guéant. I paid no attention to the rest because normally I concentrate my attention on the principal host. We spoke a bit about everything and nothing in particular, in the manner of breaking the ice, then there was a head-to-head that lasted five or seven minutes at the most. Everyone left, including me. Sarkozy and the Guide spoke in English, in approximate English – I say that because I had the recording – in bad English, but everyone understood each other.

Mediapart: What subject did they talk about during this head-to-head discussion?

They talked about the brother-in-law of the Guide, Abdullah Senussi, and the verdict in absentia [Editor’s note: in 1999 a Paris court handed Abdullah Senussi, who was Gaddafi’s internal security chief, a life sentence 'in absentia' for organising the bombing of a French airliner over Niger in 1989 which left 170 people dead]. After Sarkozy left, I received the recording in order to know the precise contents of the conversation.

Mediapart: Was there the issue of the election?

M.M.: No, there was question only of Abdullah Senussi. Afterwards, we came back inside. It was then that Nicolas Sarkozy declared, ‘I intend to present myself at the next presidential election’. The Guide replied that he was very pleased and he added: ‘It is very good to have a friend as the head of France’, then ‘We encourage you and we are ready to back you, to support you’. That’s all. Diplomatically, what is the support? I am used to such terms. When one says to a head of state ‘we are going to support you’, that means ‘We will give you money’. Because Libya can give nothing else to France. Neither perfume nor Camembert, nor Rafales [French fighter jets]. And that’s all. Afterwards, he left.

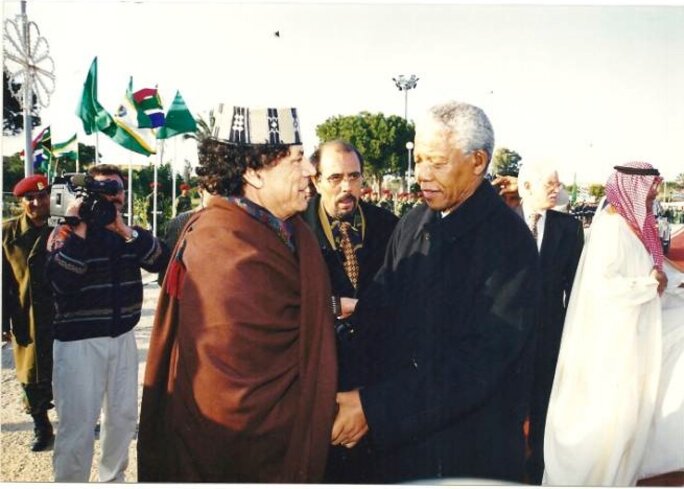

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Mediapart: At what moment did you notice Ziad Takieddine?

M.M.: At the time of leaving the tent. I saw several men, sitting on plastic chairs, including Ziad Takieddine.

Mediapart: By what means were the talks with Muammar Gaddafi recorded?

M.M.: A Swiss recording machine that was hidden in a spectacle case. I always had it. During the visit of a head of state, I brought along, me or another secretary, the notebook, the pencil and the spectacle case.

Mediapart: And were transcriptions made?

M.M.: Yes. I was the one who looked after that, when there were expressions to be translated, or a bit of conversation in English or in French. And there was also an archive department, which numbered many civil servants and interpreters, overseen by the brother of [Libyan secret service chief] Moussa Koussa, Isa Koussa who was the head of archives.

Mediapart: Have you heard mention of the visit by Brice Hortefeux?

M.M.: That was what I was going to tell you. Afterwards, I learnt – I did not see – I learnt that a meeting was held between those responsible for the campaign by candidate Sarkozy - Brice Hortefeux and Ziad Takieddine – and three Libyan officials: Moussa Koussa, Abdullah Senussi and Bashir Saleh, the guide’s foreign relations secretary. That was his true title, he was not chief of staff. That meeting resulted in a one-page document that I have seen at your place, on Mediapart, but also on the desk of the guide, because I used to come and go from his office at will. And you know the rest.

The document concerns a sum of 50 million euros. The Guide reduced by more than a half the contribution, [down to] 20 million dollars – although that could be an amount in euros. Ultimately, the currency is of little importance. With the Guide, we had a budget – if I may say so, separate to The Budget – and briefcases containing sums of money, 500,000, 1 million, 2 million, 3 million and so on, which could be handed over. The Guide was never miserly. And that’s normal, all heads of state give out money, it’s called political aide.

I don’t work with ministers, and I’m not in the loop about what is being hatched in the ministries. But when a document arrives where I am, meaning where the Guide is, I see this document because of, or thanks to, my profession.

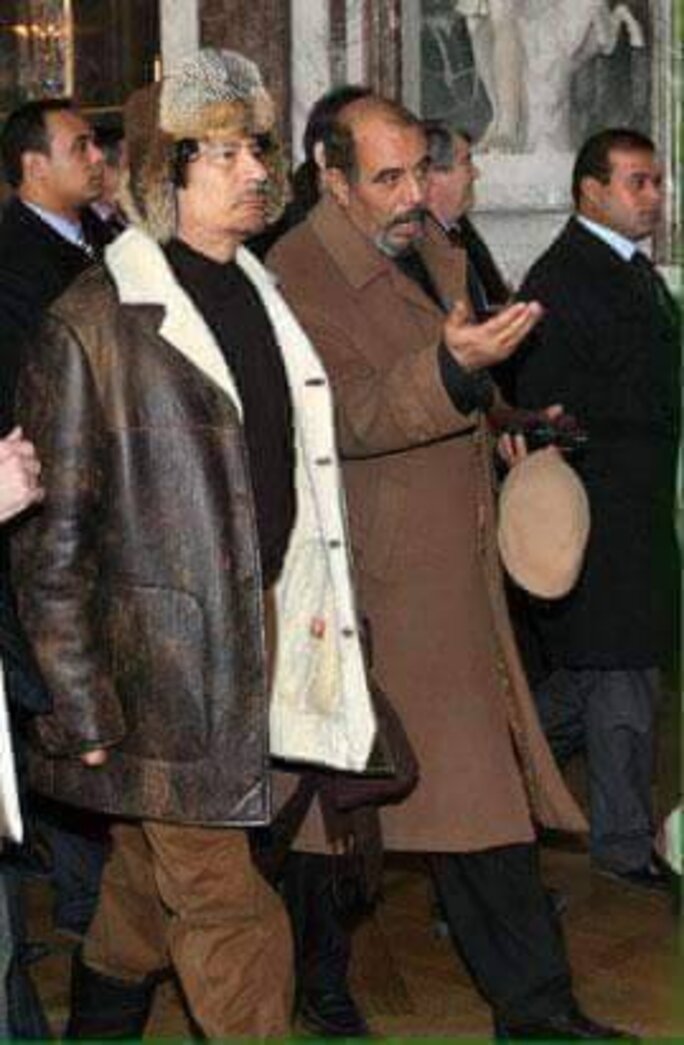

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Mediapart: Under questioning, Abdullah Senussi explained that Ahmed Ramadan, secretary of the [Libyan] presidency, had transmitted payment instructions.

M.M.: Yes, Ahmed Ramadan received the instructions, and then he called the chief accountant, Salem al-Qomodi, to tell him to give such and such a sum to such and such a person. Supposing you were the chief accountant, I come along and you give me the sum and I sign a piece of paper. There are some who just sign, and there are others, more meticulous, who sign and indicate that 'it is for the account of X or Y'. And this receipt, this slip, is kept by the chief accountant. Ramadan was the principal secretary, above Bashir Saleh. Bashir Saleh was no-one compared to Ahmed Ramadan. Ramadan was above everyone, apart from the Guide. Today he’s still detained in Libya, along with Senussi, Baghdadi and the others.

Mediapart: You speak of political aide, and it is true that Abdulla Senussi, then Moussa Koussa, had headed up a service of logistical and financial support for movements and parties in developing countries. This service was called the Mathaba, “the base camp”.

M.M.: Of course, there were already these briefcases during the time of the Mathaba. But if you take the French Minister of Foreign Affairs, you will find colossal amounts spent for cooperation programmes in countries where France wants to ensure its presence. It’s the same for Libya, and for everyone. This aide exists in every country in the world.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Mediapart: Several days after the election of Nicolas Sarkozy, there was a telephone conversation between Gaddafi and Sarkozy.

M.M.: Yes, it was a curtesy call, of congratulations. Obviously, every call was recorded. When I arrived at the presidency I put in place a document of minutes for this type of high-level exchange. A page, [for] after the bowing and scraping: president Sarkozy asked for this and that, and president Gaddafi answered this and that. And when president Gaddafi wanted to check on what was said, I would come up with the document of minutes to quickly consult it, and if there was a difficulty the recording would be sought.

Mediapart: After that, the process for the freeing of the Bulgarian nurses began. Did you become involved during the visit by Cécilia Sarkozy? What role did she play?

M.M.: Everything was prepared. She spoke with no-one except me. She had been friendly with me, and she asked the Guide for me to be present, and the Guide said to me jokingly ‘Go with your friend’. During the freeing of the nurses, I stayed with her until 3 in the morning. It is me who wrote up the convention signed by the prime minister and the European Union delegation – which Mrs Sarkozy had refused to join up with. She had said to me that European Union or not, she was not concerned because she had come for a particular mission: [She said]‘I have come here to take delivery of a parcel. Either you give me the parcel or I will leave.’ She had arrived aboard the presidential plane.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Mediapart: She spoke of a ‘parcel’?

M.M.: Yes, the nurses. ‘You give me delivery of the nurses and the Palestinian doctor, my husband sent me to take delivery of the parcel, it’s not to discuss with anyone, whoever.’ At the time of the meal at the hotel, when we were eating with Claude Guéant and a secretary, not very far from [French] ambassador Jean-Luc Sibiude, we noticed that someone was coming towards us. Cécilia Sarkozy said to me, ‘Who is that?’. I answered her, ‘It’s Libyan prime minister Baghdadi’. She repeated to me that she did not want to discuss with anyone. I told her not to worry, but that one could not tell a minister to clear off. The prime minister sat down beside me. I served as interpreter for him.

She told me to say to him, ‘I have not come here to hold discussions, I have come to accompany the nurses and the doctor, that’s all, and that these were the ‘instructions’ of her ‘boss’. Baghdadi looked at me with a flabbergasted expression. I said to him in Arabic, ‘Me, in your shoes, I’d get away’. But he replied to her, ‘Madam, I am the prime minister of this country, and I am at your disposition at any time’. I translated the sentence and he left.

Later on, Cécilia Sarkozy came back, after her divorce [from Nicolas Sarkozy]. Baghdadi called upon my presence when she was in Tripoli to present her new husband, Richard Attias, with the aim of making deals, investment perspectives and business for him.

Mediapart: The liberation of the nurses and the doctor was followed by Sarkozy’s visit to Tripoli, then by Gaddafi’s visit to Paris. How did the reception in Paris work out, in the context of increasing criticism [of the invitation to Gaddafi to visit France]?

M.M.: The French president had softened all that, explaining that people made statements but that it was not the official point of view, nor the personal opinion of Sarkozy. It was fine, it was a very honourable reception. President Gaddafi said to me, ‘You studied here, be my guide’. I was a bit his guide, I showed him the dome of the Sorbonne [university building] where I studied, the Latin Quarter.

We went hunting [in the hunting reserve for French presidents at Rambouillet, west of Paris] with the head of the [French] parliamentary Franco-Libyan friendship group, Patrick Ollier, husband of the former defence minister [Michèle Alliot-Marie, who at the time of the visit was interior minister]. It was me who picked up the game, the pheasants. Then, on the way back, we stopped alongside the book-vendor stalls on the quai d’Orsay [in central Paris] where Gaddafi bought some books, causing a traffic jam.

Numerous meetings were organised with businessmen who Mr Ollier had brought along any old how. There were also technical delegations with us from every sector because, in July, Sarkozy had spoken about sales by France of Milan missiles, of a civil nuclear power plant, Rafale [fighter] planes, of everything that Libya wanted. Relations were looking excellent.

Mediapart: To your knowledge, did the negotiations over these arms sales continue?

M.M.: Yes. Four months before the beginning of the hostilities [of the NATO-led French and British bombing campaign to overthrow the Gaddafi regime in March 2011], Claude Guéant came to see president Gaddafi accompanied by another interpreter who called the Guide ‘tonton’ [French familiar slang for ‘uncle’]. It was perhaps Boris Boillon [former French ambassador to Iraq, then Tunisia]. I received the recording of the conversation. Guéant had come with a technical document that compared the performance of the Rafale with those of the Russian Sukhoi fighter plane, and he wanted to convince the Guide to buy Rafales.

Meanwhile, according to the recording, the Guide had [previously] asked Guéant to give him the list of Libyans who had taken French nationality, and those who had properties in France. Guéant told the Guide that only one Libyan official had a house in France. He mentioned Moussa Koussa, the former head of the foreign intelligence services. He didn’t speak of Bashir Saleh [who had a house in France’s Ain département, close to the Swiss border]. He gave him a list of dual nationals and, apart from one or two individuals, like the housing minister, it involved ordinary people.

Guéant also told the Guide that Bashir Saleh had begun a naturalization process [to obtain French nationality]. He asked him if it should be left in process or halted, and the Guide replied ‘Don’t do anything’.

Mediapart: The subject of the funding [of Nicolas Sarkozy’s 2007 presidential election campaign] was raised with you in March 2011 during an interview with Le Figaro journalist Delphine Minoui. In the end, the daily did not publish that key moment in the interview, but the journalist revealed it in her book ‘Tripoliwood’. It was at that moment that the sum of 20 million was presented.

M.M.: Yes, the journalist asked president Gaddafi lots of questions about the revolution, the insurrection, the position of France, and then at the end she said to him, ‘Did you contribute to president Sarkozy’s electoral campaign?’, and he said: ‘Yes, of course, I contributed.’ And the journalist asked him, ‘to what amount?’. The Guide replied to her: ‘I don’t remember any more. Tomorrow, I will tell you.’ The journalist was leaving early in the morning, so he told her to leave her contact details with me.

The next day, he said to me: ‘I’ve checked up and the sum is 20 million dollars’. I don’t know if it’s really in dollars or in euros, but that’s what he said to me. The manner in which the money was sent didn’t concern him. I am not telling you that I saw briefcases, I’m telling you what the Guide told me.

Mediapart: Was this interview, like others at the time, a sort of call by Gaddafi for the suspension of hostilities against him?

M.M.: Yes, there were several calls. And the last letter project I received from the Guide was a letter in Arabic that I was to translate into French. I translated this document, which I gave to Bashir Saleh who took it to Sarkozy. This letter spoke of a respite and a peaceful solution to the Libyan problem, to the insurrection. The Guide was ready for discussions concerning himself on the subject of his withdrawal, on condition he stayed in his country, as a protocol figure. It was the last missive by Gaddafi that I translated, at the end of June, beginning of July [2011].

Mediapart: The major mystery remains over the rupture in relations between the two heads of state before the launching of the war.

M.M.: The Guide was staggered at this dramatic turn on the part of his friend. Sarkozy had said, ‘I’m not a friend for a day, but a friend for always’, and then he changed his mind like changing his tie. He was perhaps humiliated by these promises for contracts that were not honoured, the Libyan gas affair, the withdrawal of Libya from the Union for the Mediterranean. In reality, we don’t know.

-------------------------

- The French version of this interview, conducted in French, can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse