India’s prime minister Narendra Modi is to be French President Emmanuel Macron’s guest of honour at this year’s Bastille Day military parade in Paris on July 14th, which will notably include a flypast of Indian Air Force (IAF) Rafale fighter aircraft.

The four IAF Rafale jets taking part are from among 36 of the Dassault-built fighters India bought from France in 2016, in a 7.8-billion-euro deal that has become the centre of a suspected corruption scandal involving politicians and industrialists, and which is the subject of an ongoing French judicial investigation.

Macron’s invitation to Modi to be guest of honour at the Bastille Day ceremonies has dismayed human rights organisations who denounce the Hindu nationalist’s increasing attacks on fundamental freedoms in his country, frequently described by the media as “the world’s largest democracy”.

Amnesty International has detailed an alarming situation in India, including the judicial hounding of opposition leader Rahul Gandhi, organised discrimination and violence against religious minorities, notably Muslims, crackdowns on freedom of expression, tax office and police raids against NGOs and media organisations, and the arbitrary arrests and detention of journalists and rights activists.

But Modi’s authoritarian drive has not deterred Macron from engaging in a strategy of realpolitik with the Indian leader, as he hopes to complete a number of bi-lateral deals with his guest, notably for the sale of French submarines and orders for further deliveries of the Rafale fighter jet. It is the continuation of a strategy employed by his predecessor, François Hollande, who in 2016, when Macron was his economy minister, signed the initial deal with Modi for the sale of 36 Rafale jets designed and built by Dassault Aviation.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Hollande was French president from 2012 to 2017. Macron served as Hollande’s deputy chief-of-staff from 2012 to 2014, and subsequently as the socialist president’s economy minister between 2014 and 2016, when he resigned to launch his successful bid for the presidency in elections in 2017.

But as Paris now prepares to roll out the red carpet for the Indian prime minister later this week, a menacing cloud is closing in on both Modi and Macron in the form of the now two-year-old French judicial investigation into suspected “corruption”, “influence peddling” and “favouritism” surrounding the 2016 Rafale contract.

Mediapart has learnt that the Paris magistrates in charge of the probe have sent an official request to the Indian authorities for their cooperation with the investigation. The magistrates are notably interested in studying the case files of two Indian investigations which, as Mediapart has previously revealed, detail evidence that Dassault secretly paid several million euros to India-based business intermediary Sushen Gupta in its attempts to secure the deal signed in 2016.

Five years after the discovery of that evidence, contained in confidential documents unearthed in a separate corruption case, the Indian justice authorities have still not opened an investigation specifically into the circumstances of the Rafale fighter jet sale. If the cooperation request submitted by the French magistrates was to be refused out of hand by the Indian authorities, it would show New Delhi’s intent to definitively bury this sensitive affair.

Meanwhile, Mediapart can today reveal a key episode in events connected to the Rafale deal, and which emerge from confidential documents from France’s tax administration. Some of these, according to sources, have been added to the evidence collected so far in the French judicial investigation.

They concern Indian billionaire Anil Ambani, the chairman and owner of the industrial and services conglomerate Reliance Group, and who is personally close to the Indian prime minister. It is suspected that Ambani’s group was, in negotiations over the Rafale deal during the spring of 2015, imposed upon Dassault as its local industrial partner. Reliance became the main beneficiary of the lucrative subcontracting work, in what is called an “offset” agreement, for the benefit of the local economy.

At the same time as this was arranged, a French subsidiary of Reliance, called Reliance Flag Atlantic France, which had a tax debt of 151 million euros, was finally granted, as first revealed by French daily Le Monde, a generous adjustment agreed with France’s tax administration which reduced the sum owed to 6.6 million euros, a saving of more than 144 million euros.

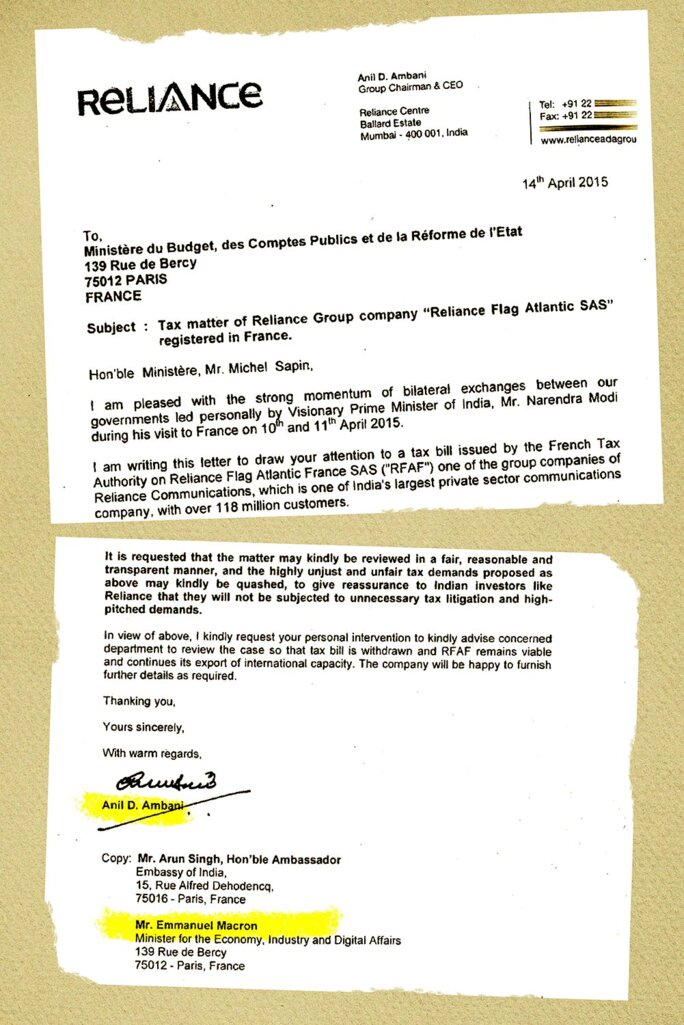

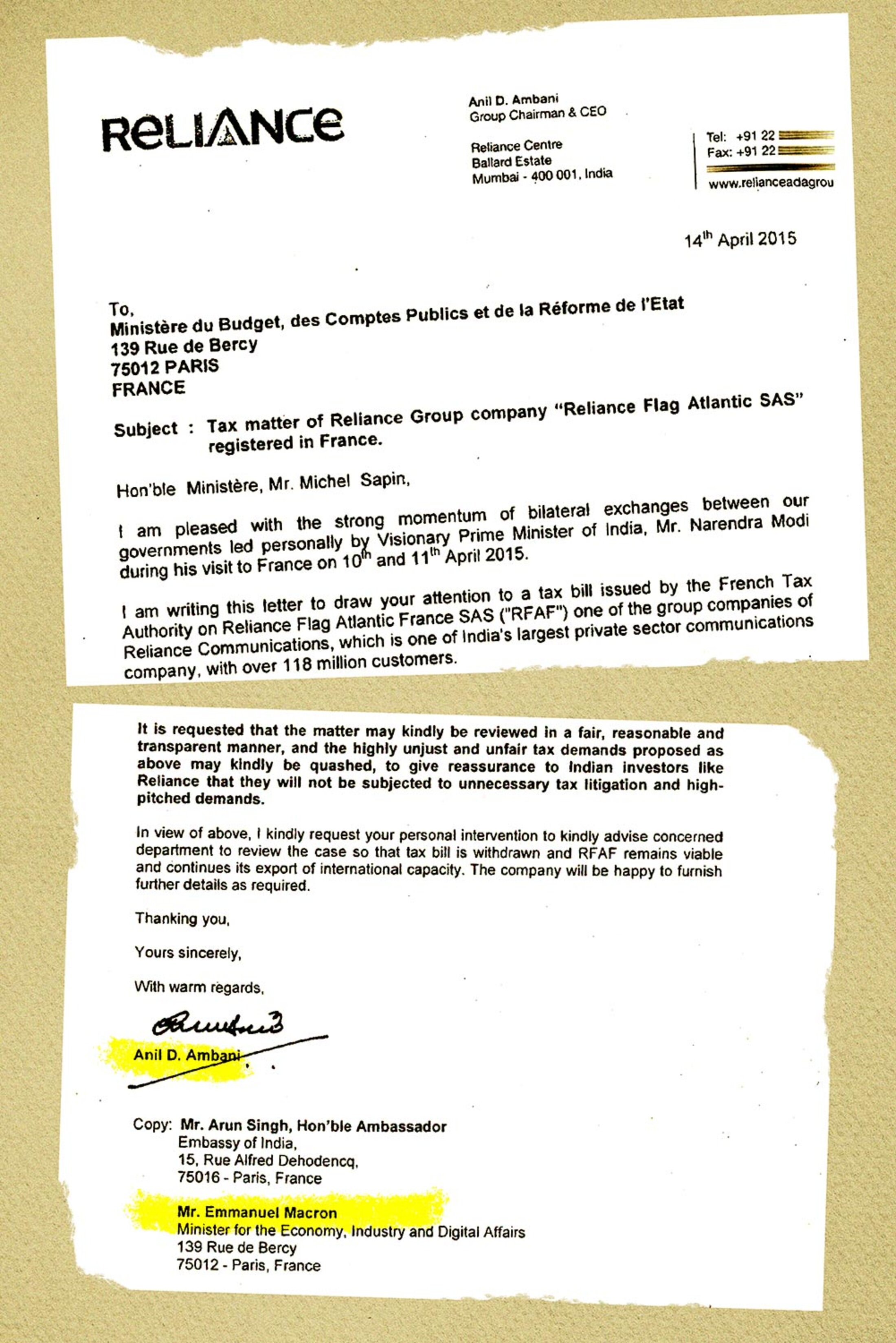

Documents now obtained by Mediapart reveal that the office of the then finance minister, Michel Sapin, was involved in the tax adjustment following a letter addressed to it by Ambani, dated April 14th 2015, a copy of which was also sent to then economy minister, Emmanuel Macron.

Macron’s involvement raises questions because, at the time, he had no authority over the public finances directorate, the Direction Générale des Finances Publiques (DGFIP), which was instead directly answerable to Sapin. Le Monde also reported that a Reliance employee close to Ambani recounted, on condition his name was withheld, of how he and Ambani, in early 2015, had met with Emmanuel Macron at his ministerial office, “where the tax problem was settled in a phone call to his administration”.

Questioned by Le Monde about that comment, the French presidential office, the Elysée Palace, said Macron’s former advisors at the economy ministry had no recollection of a meeting between him and Ambani. Macron has not personally confirmed or denied that the meeting took place, and he did not reply to questions Mediapart submitted to him about the matter.

While Ambani wrote to Sapin in person, the former finance minister told Mediapart that he had “no recollection” of it. “The only possible thing that my cabinet [ministerial staff] may have done is to transfer the correspondence to the DGFIP for [their] study,” he added. “But it is impossible that they gave an order regarding the manner of treating a tax affair. This was a principle, we never did that.”

As to whether the intervention paid off, a source at the economy and finance ministry told Mediapart that it had no effect on the final settlement. Consulted by Mediapart, fiscal affairs experts said they believed that while, for the most part, the reduction of the Reliance subsidiary’s tax debt was justifiable, the group was nevertheless given favourable treatment. That included almost no financial penalties on the debt owed, and which represented a gain of around 1 million euros. Furthermore, to consider the group as acting in “good faith” was at the very least odd given that Reliance used a structure of aggressive tax optimisation in a tax haven.

The affair is also potentially embarrassing for François Hollande, who was at the time French president. In January 2016, three months after the tax adjustment was signed, Reliance announced it was to provide 1.6 million euros in funding for the making of a feature film co-produced by Hollande’s personal partner (and now wife), Julie Gayet, as Mediapart first revealed in 2018.

Questioned by Mediapart about his knowledge of the tax adjustment and Ambani’s contact with his ministers, Hollande declared: “I was at no time involved with this approach. I therefore refer you to Michel Sapin.” Also contacted, neither the Reliance Group nor Anil Ambani replied to questions submitted to them.

The story behind the tax settlement began in 2011, when the DIRCOFI, the tax inspection directorate for the Île-de-France region – which includes Paris and its outlying départements, or counties – turned its attention to Reliance Flag Atlantic France, which operated a cross-Atlantic undersea telecommunications cable linking France and the US. Officially, the Reliance subsidiary was losing money and as a result paid no company tax.

However, the French inspectors discovered a system that is emblematic of international tax evasion and avoidance practices. This involved transfer pricing, which concerns transactions between corporate entities that are under common ownership. Reliance artificially transferred the profits from its French subsidiary to the mother company of its telecommunications activities, Reliance Globalcom Limited, which is registered in Bermuda, the British overseas territory which until recently featured on the European Union’s blacklist of non-cooperative tax havens.

Such procedures are complex, and the company was legally obliged to provide detailed documents of its internal operations in order for the tax authorities to be able to estimate what amount was liable for taxation in France. But Reliance refused to provide the details demanded of it.

The French tax authorities decided that the internet output which Reliance Flag Atlantic France (RFAF) bought from the mother company could not be deducted from its revenue, even though the purchase is real. As a result, the total of profits liable for taxation jumped dramatically, and RFAF was handed a demand for a backpayment of 151 million euros in taxes and penalties for the period 2008-2012. While the amount did not correspond with the economic reality of the situation, it was justified at a legal level; when a company refuses to supply documentation of its financial flows towards a tax haven it is heavily penalised.

“It’s a classic strategy,” commented one tax expert consulted by Mediapart, who requested that his name is withheld. “The tax authorities come up with the atomic weapon to push the company into providing the documents and reach an amicable settlement. It is therefore normal that there is a very steep reduction of the tax due if the company finally plays the game.”

In the case in point, it took two years until, at the end of 2014, Reliance changed its strategy and finally provided the requested documents. On February 16th 2015, the DIRCOFI accepted the principle of a transaction based on the standard model in such cases, by which the tax office calculates the costs of operations and profits of the company, according to its sector of activity. Reliance proposed paying 6.2 million euros, arguing a rate of profit of 3%. The French tax office decided that this was too little.

But Ambani had a trump card to play. On March 26th 2015, Reliance became designated, in all secrecy at first, as Dassault’s new principal Indian local partner in the as-yet unsigned Rafale contract.

Originally, the tender won by Dassault was for the supply of 126 fighter jets, of which 108 would be built in India by the state-owned aerospace and defence corporation Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), which the Indian government had in 2012 appointed as Dassault’s principal industrial partner. But that would change three years later.

I kindly request your personal intervention [...] so that tax bill is withdrawn [sic]

On April 10th 2015, Modi, who was elected to office the previous year, made an official visit to Paris, accompanied by a delegation that included Ambani, when he announced to general surprise that the terms of the original tender were to be overturned, and instead India would purchase just 36 Rafale jets, all of which would be manufactured in France. HAL was sidelined from any further involvement.

In all probability, with the Rafale deal still not inked, the French authorities would have been cautious not to upset Ambani, whose group was appointed as Dassault’s new principal partner by Modi’s government, as François Hollande confirmed in a previous interview with Mediapart, adding that France “didn’t have the choice” in the matter. The Indian government, Reliance and Dassault all denied the former French president’s version of events.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

On that same day of April 10th 2015, lawyers representing Reliance began a second round of negotiations with the French tax administration at a meeting at the DIRCOFI headquarters in the northern Paris suburb of Saint-Denis. At the same time, according to sources, Ambani, who was in the French capital as part of Modi’s delegation, took the opportunity to complain to officials about the back-tax claim of 151 million euros – which still applied as long as a compromise had not been found.

On April 14th, four days later, Ambani addressed a letter directly to finance minister Michel Sapin, with copies of it to sent economy minister Emmanuel Macron and the Indian ambassador to France. “I am pleased with the strong momentum of bilateral exchanges between our governments led personally by Visionary Prime Minister of India, Mr. Narendra Modi during his visit to France on 10 and 11th April 2015,” it began.

The Reliance boss went on to detail his arguments against what he called “extreme and unreasonable situation” of the huge tax adjustment. “It is requested that the matter may kindly be reviewed in a fair, reasonable and transparent manner, and the highly unjust and unfair tax demands proposed as above may kindly be quashed, to give reassurance to Indian investors like Reliance that they will not be subjected to unnecessary tax litigation and high- pitched demands,” he added.

The letter concluded: “I kindly request your personal intervention to kindly advise concerned department to review the case so that tax bill is withdrawn and RFAF remains viable and continues its export of international capacity [sic].”

But in the preamble, Ambani told Sapin that he was “delighted with the strong momentum of the bilateral exchanges between our governments, led personally by the visionary prime minister of India, Mr Narendra Modi, during his visit to France on the 10th and 11th of April 2015.”

The reaction was swift. On April 20th 2015, the central directorate of the tax inspection services wrote to its regional office asking for a copy of the Reliance case file “following the written request by the company (Indian CEO) made directly to the minister”, which was a reference to Sapin. The relevant documents were sent to the directorate by the regional office the very same day.

The next day, the head of Ambani’s other French subsidiary, Reliance France, wrote to Sapin, with copies sent to Macron, Ambani and also India’s ambassador. “I am pleased to inform you that an agreement has been reached on the terms of a settlement with the French Tax Authorities […] and that, in our opinion, this represents an equitable and appropriate settlement in all the circumstances,” she wrote, adding: “We have been requested by Mr. Anil Ambani to advise you that (a) we do not require any further assistance from your department and (b) the request set out in his letter of April 14, 2015 is hereby withdrawn.” She concluded by thanking Sapin “for your time and attention to this matter”.

When Reliance France’s tax affairs lawyer passed the letter on to the French public finances directorate, the DGFIP, she expressed how she was bothered about what she called a “successive palaver of intervention and withdrawal of intervention”, which she said was the result of a simple misunderstanding, and that Ambani “had called upon the French finance minister” whereas the negotiations were progressing well. “All of that was done to our great surprise, and I would even say without us knowing!” she wrote, adding that the Reliance boss ended his involvement after becoming aware “that the exchanges with the French tax administration had been more than constructive”.

Which raises the question of whether the original request was truly “withdrawn”, or whether that was an attempt to clear the ministers, in advance, of any suggestions of interference. None of the main parties involved commented on the matter.

The deal with the tax services was formally signed six months later, on October 22nd 2015. Reliance paid 6.6 million euros for the period concerned by the tax adjustment, from 2008 to 2012, and another 700,000 euros to bring the following two years into line with the terms of the 2008-2012 adjustment.

Experts in tax affairs who were consulted by Mediapart said they believed the principle of the deal and the method employed was largely justified, and that as of the moment Reliance began cooperating by supplying the requested documents it had a good chance of obtaining the annulment of the original 151-million-euro tax claim.

But those same experts also underlined that Reliance received rather favourable treatment for what amounted to a case of international tax evasion. In the initial tax adjustment, the French inspectors had, on top of the sum of the back taxes, added financial penalties amounting to 31% of that sum. In the final agreement, the penalties were reduced to just 4%, totalling 210,000 euros, representing a saving for the Indian group of around 1 million euros.

To all appearances, Reliance was treated as a taxpayer acting in good faith, even though the group had mounted an aggressive tax optimisation structure in Bermuda, and took two years before it finally agreed to cooperate with the French tax authorities.

Contacted by Mediapart, the DGFIP did not reply to the questions submitted to it.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse