It takes time to get used to, and to distinguish, the voices of“Mario” (Draghi), “Pierre” (Moscovici), “Wolfgang” (Schaüble) and “Christine” (Largarde). Patience is also needed to master the very technical jargon being spoken, often in approximate English. The only figure around the table who speaks a different language is France’s then finance minister, Michel Sapin, who expresses himself in French.

The quality of the recordings, which were made on a smartphone placed on the table, varies between the meetings, and sometimes adds to the difficulty in understanding (listen to extracts in the accopanying article here). The recording of a video conference on June 24th 2015 is marred by the tinkling sounds of cutlery.

But once the ear becomes adapted, a hitherto unknown world emerges, made public for the first time since the creation in 1997 of the Eurogroup, an informal gathering of the 19 finance ministers of the countries that have adopted the euro as their currency, a body which is barely mentioned in official European Union texts, buried in the agreements of the Treaty of Lisbon.

Most of the officials around the table are men. The most muffled voices are those sitting furthest away from the Greek delegation, such as then German finance minister Wolfgang Schaüble, or Pierre Moscovici, then European commissioner for economic and financial affairs. Among the most audible are Spanish economy minister Luis de Guindos, and his Italian counterpart Pier Carlo Padoan, who were both sitting close to Yanis Varoufakis, the then Greek finance minister who was making the recordings.

The some 15 hours of recordings which Varoufakis has decided to publish now, and which Mediapart was given access to (see 'Boïte Noire' box bottom of page), provide a fascinating insight into a closed chamber, one that was intended to be safe and secret from the outside world, and notably European citizens.

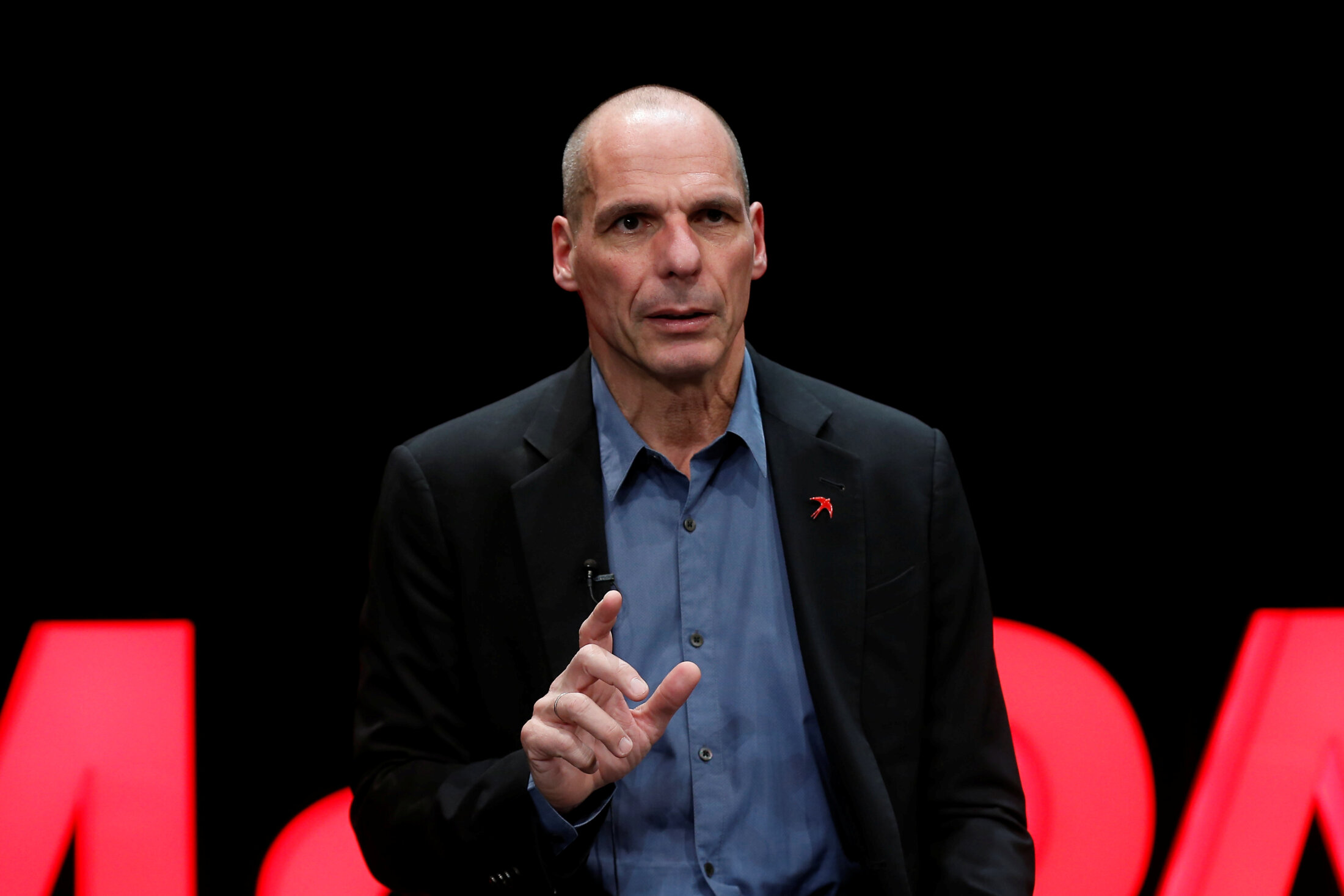

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Back in early 2015, Greece was facing a crisis so vast that its economic future, and more immediately its membership of the eurozone and by ricochet the european union, was at stake. Beyond that, the European Left were gripped by the question raised by the newly formed Syriza-led government in Greece, namely whether there was a margin of manoeuvre within European treaties to adopt unorthodox economic policies after decades of German-inspired ordoliberalism.

Following the arrival in power of the radical-left Syriza party in January 2015, newly appointed Varoufakis went on to attend 13 meetings of the eurozone ministers, beginning in February and up until July. He decided to record the discussions as of the fourth meeting, on February 24th 2015.

Varoufakis, now a Member of Parliament in Greece, on Friday posted online what he describes as the totality of the verbal exchanges from ten of the meetings, most of which were held in Brussels (although one key meeting of the Eurogroup took place on April 24th 2015 in Riga, the capital of Latvia, which at that time presided the rotating six-month presidency of the EU Council of Europe). Despite the success of his 2017 book recounting the events of 2015, Adults in the Room: My Battle with Europe's Deep Establishment (which was subsequently made into a film, Adults in the Room, directed by Costa-Gavras and released last year) there remain two opposing versions of the six months of negotiations in Brussels.

Within the EU institutions, as also within the Syriza party – which was defeated in parliamentary elections last year when the conservative New Democracy party took power – it is argued that the failure of the negotiations is above all due to the personality of Varoufakis. He has been accused of narcissism, of having a volcanic temperament, stubborn in conflict and incapable of formulating reasonable propositions. The accusations are firmly rejected by Varoufakis, who hopes the recordings published now will disprove them. He argues that he continuously tried to build bridges with Berlin, agreed concessions and put forward countless propositions which were rejected one after the other without ever being properly discussed – all of which for him is the evidence of a dysfunction of democracy in the European bloc which will break up if it does not swiftly reform itself.

The 2015 negotiations can be regarded as being structured in three acts. Firstly, during the first meetings held in February, there was an agreement to extend the aid programme for Greece that had been established in 2012 and which was due to end on February 28th. The second act came in Riga, in April, when tensions mounted and as the deadline for a further bailout loomed the threat of a ‘Grexit’ appeared. The hard line towards Greece adopted by Schaüble was gaining support among the Eurogroup. Varoufakis left that key meeting in a weakened position.

Finally, in June and July, the third act in the negotiations saw them continuing for form, at an increasing rhythm of meetings (in the recordings made by Varoufakis, Schaüble on June 24th commented on the recurring meetings: “I don’t like to spend so much time in the Eurogroup. Some of us have other schedules as well. Other obligations. Brussels is nice but I cannot stay for days waiting for someone to make some agreement.”)

But it can be understood that the essential decision making lay elsewhere, without Varoufakis and at the level of heads of state and government. Around the negotiating table, divisions deepened between the European institutions and member states (notably during the June 25th Eurogroup meeting), up until the announcement that Greece was to hold a national referendum on whether to accept or reject the bailout conditions of the so-called Troika – made up of the European Commission (EC), the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). The referendum was held on July 5th, when the bailout proposition was rejected by a large majority. But then Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras, elected on an anti-austerity platform, was to make a complete U-turn, agreeingthe tough bailout conditions. Meanwhile, Varoufakis had left the scene, replaced as finance minister by Euclid Tsakalotos.

One person who had taken part in the negotiations, speaking to Mediapart on condition their name was withheld, said that, “At the end it became a personal issue, Varoufakis versus Schaüble. What was totally cocked up was to put the same people for six months in the same room, in the end almost every day. It could only lead straight into the wall. We all had a feeling of impotence.”

Contacted by German weekly Der Spiegel, with which Mediapart worked in partnership on this investigation, Schaüble commented: “It is no longer of any importance that Varoufakis today publishes these recordings which were made without us knowing,” adding: “The five months with Varoufakis are a grossly overestimated chapter.”

The recordings show that from February to July 2015, a very heavy atmosphere hung over the Eurogroup meetings, recurrently marked by hostility towards Greece. The only note of humour that Mediapart could find in the exchanges was a comment – although hardly hilarious – made on June 22nd by Jeroen Dijsselbloem, the Dutch president of the Eurogroup and an ally of Schaüble. When Varoufakis, who had frequently been photographed riding his motorbike in Athens, arrived late for the meeting that day, Dijsselbloem quipped: “Sorry we started without you. We did not know how close or how far you were. Some suggested that you were coming by motorbike from Athens but luckily you were quite close.”

'Communication is critical'

The decision by Varoufakis to publish the recordings is in part to demonstrate with force one of the issues presented in his book, namely the second place given to political debate between member states' ministers in favour of the supposed expert propositions of the three institutions of the Troika (the EC, CEB and the IMF).

At each meeting, the representatives of the Troika (these were in general the ECB president Mario Draghi, who was sometimes assisted by French economist and ECB board member Benoît Cœuré, IMF managing director Christine Lagarde, and the EC’s Pierre Moscovici, who was occasionally accompanied by fellow commissioner Valdis Dombrovskis, a Latvian conservative who Varoufakis claimed was present to watch over Moscovici) presented an updated economic overview. The Eurogroup president would then invite the Greek minister to speak, followed by other ministers present. The framework of issues for discussion as fixed by the Troika institutions was never placed in question.

The most striking example of this was at a meeting on June 18th 2015, when Varoufakis had just finished presenting his government’s proposal to introduce a reform that he described as an “automated hard deficit brake”, by which “a failsafe system will be in place that ensures the solvency of the Greek state and its primary surplus while the Greek government retains the policy space it needs in order to remain sovereign and able to govern within a democratic context.” Eurogroup (EG) president Jeroen Dijsselbloem then replied that “any new proposals brought today must be looked at by the institutions. It is not for the EG to assess them”.

That same day, French economy and finance minister Michel Sapin discreetly challenged Dijsselbloem. “I would like the Eurogroup, which is not a technical place but a political place, to be able to make a contribution, give its opinion, even if the decisions must be taken at the highest level [editor’s note: between the heads of state and governments].” But Sapin’s suggestion drew no support from others in the room, prompting Varoufakis to tell them: “In my presentation I made what can be considered a major proposal about a hard deficit brake. And I am very surprised that there was precisely zero discussion of it – I must make a note to remember this. This is rather strange for a forum which supposedly was interested in the ideas that the Greek government had to offer.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The arguments of the technocrats took the lead over political discussions. No studies of the Greek crisis by outside economists were debated at the meetings, despite them being numerous at the time. No doubts, hesitations or self-criticism were uttered by either camp. To be credible, it seems, the participants had to hide behind technical jargon. In his book, Varoufakis poignantly remarks that the Eurogroup meetings demonstrated to what extent the Troika and its methods had taken hold over the governance of continental Europe,

It was at just one of the ten meetings recorded by Varoufakis that ministers present spoke before the representatives of the Troika. This was on June 27th, when the gathering had been hurriedly called just after the announcement by Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras that a referendum was to be held on the bailout terms. Varoufakis was the first to speak, entering into a long and detailed commentary of the issues under negotiation. It was not rare for his contributions to last around 20 minutes, whereas others would often speak for just two or three, and when no-one would interrupt him with questions these can appear as monologues.

The absence of debates on substance compares with the preoccupation of ministers about how to present their discussions to the outside world, seeking agreement on the language to be used and to mask dissensions, even if no progress is being made and the marathon of meetings are heading ever closer to failure. At a meeting on February 24th 2015, Spain’s conservative economy minister Luis de Guindos, insisted that, “On communication: schizophrenic approaches create problems. All messages should be fully aligned. Unnecessary noise is not going to be very helpful”. Varoufakis approved. The only contribution from the Portuguese finance minister, Maria Luisa Albuquerque, also a conservative, was on the same subject: “Communication is critical,” she said. “We should have an agreement on what we should communicate. Will there be a statement today?”

Two months later, at the meeting in Riga on April 24th, De Guindos, who appeared obsessed throughout the discussions with the questions of panic on the financial markets rather than debating the position of the Troika, reacted to the stalemate of the negotiations. “When we have to face up a situation with such a gap it is hard to manage expectations and communication,” he said. “So, I think that I fully agree it is not wise to set up new deadlines, but I think that we need something to say in our communication. Don’t know if you have prepared something. We are running out of time but we need to do our utmost to find a solution. But I do not know what message we can convey after this meeting.”

At another meeting on June 18th, De Guindos commented: “We are coming to a head and there are events out of our control. We should have a communication. The reaction of Greek depositors will not be positive, we must bear it in mind, it is the reality. I think, Jeroen [Dijsselbloem], you should prepare any sort of communication to make sure that, in any potential scenario, the integrity and irrevocability of the eurozone is guaranteed in any potential scenario.”

At the June 24th meeting, Wolfgang Schaüble tackled Dijsselbloem, Lagarde and Moscovici over their press conference presentation of the previous talks of the Eurogroup. “I would like to say too that the creation of wrong expectations is dangerous […] By the way when I followed the press conference after our last meeting I was a little surprised, wondering whether I was in the same Eurogroup. Because the atmosphere at the press conference was much more positive.”

'I think we should talk about Plan B'

The recordings released by Varoufakis also confirm the extent of Germany’s hegemony at the time – and the weakness of French influence. The principal, imposing figure among the Eurogroup was Schaüble. A Christian Democrat who at the time was aged 73 and who had been confined to a wheelchair after surviving an assassination attempt against him in 1990, he was in favour of a provisional ‘Grexit’, even though Chancellor Angela Merkel adopted a more prudent line. Schaüble spoke comparatively little at the meetings, but when he did his words counted. The six months of conversations are liberally sprinkled with the phrase “I agree with Wolfgang” and mark the direction they took. His allies, mostly from the northern half of Europe, the “hawks” of budgetary discipline, were the Finns, the Lithuanians, the Austrians, the Slovaks and the Slovenians and, to a lesser degree, the Irish and Maltese. Varoufakis is scornful of them, describing them in his book as Schaüble’s “cheerleaders”.

Dijsselbloem, the Dutch president of the Eurogroup, was systematically attentive to Schaüble’s demands. At the February 24th meeting, Schaüble firmly insisted that it should be made clear there would be no deviation from the terms of a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) just signed with Greece for an extension of the bailout. “Do not worry Wolfgang, there will be no amendment to the Friday statement,” Dijsselbloem reassured him.

One of the funniest moments from among the 15 hours of recordings is a comment made by Varoufakis about Schaüble. Greek economist Euclid Tsakalotos, who would later succeed Varoufakis as finance minister, acting out the Tsipras U-turn on Syriza’s original programme, at the time accompanied Varoufakis to most of the negotiations. The two men were present at a Eurogroup meeting on June 25th which was marked by strong disagreement between Germany and the IMF and ECB. As Schaüble entered into a scathing attack on the IMF, Varoufakis turned to Tsakalotos saying, “This is why I like this guy!” It was an illustration of the charisma Schaüble enjoyed in the room.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Over the months, Schaüble occasionally took aim at the European Commission, which he considered was too lenient with Greece and which also annoyed him with its apparent desire to free itself of the IMF. At a meeting on June 22nd, Schaüble addressed Moscovici: “We are not idiots! You can play any game to blame the IMF. Without the full involvement of the IMF there is no way. I have to tell you very clearly.” But where he really excelled was in spreading the fear of the threat of Greece leaving the eurozone.

Indeed, one of the major things to be learned from the tapes is how the scenario of a ‘Grexit’ came up in the discussions well before the meetings of June and July and the results of the referendum in Greece, but as early as April, at the meeting in Riga. Furthermore, it was not Schaüble who first threatened Greece with an exit from the euro, but rather his Slovakian counterpart Peter Kazimír who, at that April 24th meeting warned: “Are we on track to meet the June deadline? This is the question for us. We are ready to help Greece. But if Greece does not need help, maybe the time has come to talk consequences.”

While Schaüble, irritated by the attitude of the Greeks, muttered “incredible, incredible,”, his Slovenian counterpart chipped in: “There is no way Slovenians, who are most exposed to Greece, can be persuaded that they put additional effort to help Greece get out of the situation. So, I think we should talk about Plan B. We have so many months, we have a few days, few weeks now. I cannot see how we can get there. I know that we did not want to talk about Plan B. We wanted, including Slovenia, to resolve this. But now I don’t see this.”

The idea of a forced Greek exit from the eurozone, the “Plan B”, had been clearly floated, and following the Riga meeting it would never leave the discussions.

Irish finance minister Michael Noonan joined the Grexiter camp at the meeting on June 18th. “I am concerned about the situation but I think that a bad agreement could be worse, more corrosive for the euro, than no agreement at this point,” he told the group. On June 25th, it was the turn of Finnish finance minister and former prime minister Alexander Stubb (who in 2018 would fail in his bid to be chosen as the conservative EPP candidate for the presidency of the European Commission) to openly rally the camp. “Option A is some kind of flexibility, conditionality, a way out of this dilemma,” said Stubb. “That will probably weaken the credibility of the euro. The other is an exit of a member of the eurozone. In the short term that would cause market and political turbulence but in the long term it may strengthen our common currency. I really don’t know. But the longer we prolong this, to take it to the 11th hour of 30th June, the worst it will be.” French finance minister Michel Sapin was one of the few to exclude the idea of resorting to a “Plan B”.

At the Eurogroup meeting of June 22nd, when then Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras had given considerable ground on his government’s budgetary policies, Varoufakis tried to salvage something in return through the waving of part of the debt. Schaüble then came up with a new threat in the form of controls on capital, asking ECB boss Mario Draghi, in a falsely naïve manner, “whether the ECB is thinking about” capital controls. Noonan said he agreed with Schaüble.

In the recordings, at that moment Varoufakis can be heard irritably scribbling a few lines of response to the comments. “You asked me Wolfgang if the Greek government is ready and willing to impose capital controls,” he told the German. “Our view, let me make this crystal clear, is that there is no need whatsoever for capital controls as long as we are successful in bringing about this agreement. The Greek public have shown immense calmness despite being bombarded both by the Greek media, by the foreign media, by us politicians with a great deal of insecurity and of terrorising news regarding bank closures, capital controls and so on. The moment we, the politicians, the technocrats, our leaders announce that an agreement has been struck, there will be no need for capital controls.”

Before finally announcing, on June 26th, the future referendum, the Greek camp appeared to be giving ground from one meeting to the next.

Varoufakis told he had become 'a kind of cartoon'

The recorded comments from the officials representing the member states, led by Germany, stubbornly resistant to solidarity with the Greeks, reveal one of the inherent difficulties for such crisis meetings of the Eurogroup. This was the clash between the defence of the project of European integration, championed by the institutions, and the demands of national mandates. Added to this are also the divisions around the table between different governments, all of them legitimate, which were far from sharing the same interests, and which brought further complications for a demonstration of solidarity.

In his book, Varoufakis did not pay particular attention to this, but it appears to have been a permanent concern for Schaüble. He was one of the rare participants to have raised, early in the discussions, the issue of satisfying the members of his parliament, the Bundestag. During February 24th meeting, when he insisted that there must be no change to the MoU that had shortly before been agreed, Schaüble said: “It must be totally clear, because [otherwise] it will create terrible problems in my parliament, that we have created no amendment to the agreement.”

There would be a series of similar warnings to the Greeks when Varoufakis challenged previous decisions taken by the Troika, with some of the ministers around the table underlined the sacrifices made by their own peoples in the name of budgetary rigour. At the April 24th meeting, the Slovak Peter Kazimír told Varoufakis: “We have agreed in February to have a comprehensive list of reforms in April. We do not have it. Instead we have had an unwillingness to cooperate, backtracking on some measures and fiscal sustainability is volatile […] I refused to the union of pensioners in my country a proposal of a 13th pension. Why? Because of fiscal responsibility and consolidation in my country. You can pay out more pensions to your pensioners if you have the money. Do you have it? I cannot support any agreement with you and at the same time refuse the 13th pension in my country and observe a 13th pension in your country. And this is backtracking.”

His Lithuanian counterpart, while accepting that Greece’s sovereignty should respected, added that “we, the rest of the Eurozone, must also have a say because what is happening in there affects our countries”.

Schaüble would never deviate from his position on this. On June 25th, rejecting the idea of launching a third aide programme for Greece, he said, irritably: “I said yesterday, no one listened. We will not agree on anything that is understood as a third programme. To do so we would have to ask for a mandate from Parliament.”

In the tapes, Sapin never once mentioned the issue of gaining acceptance of measures for Greece by his own parliament, the National Assembly, such is its lack of involvement regarding French policy in Brussels. Questioned by Mediapart, Sapin said the failure of Varoufakis in the talks was the result of an error of strategy. “He thought that it worked on a majority basis, that France and the southern countries had the capacity to form a majority to tip the scales,” he said. “But the ‘majority’ in a European system does not exist. There has to be consensus.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

The problem with reaching a consensus in European negotiations is that it can, in extreme situations, lead to absurdities. In his attempts to bring opposite sides together in the negotiations, Dijsselbloem displayed extraordinary imagination – or, his critics might say, bad faith. At the June 25th meeting, he commented: “We must ask the institutions to see if they want to work with the Greek authorities, as long as they do not deviate further.” That was tantamount to saying that the negotiations could continue, as long as no concessions were made to the Greeks.

Meeting on June 27th, the participants had learned the previous evening of the referendum the Greek government had called on whether to accept the bailout terms, set for July 5th. The Greek delegation was questioned: will the Tsipras government advise a “yes” or “no” vote? If the bailout terms are rejected, will Greece mechanically leave the eurozone? Above all, the Greek government was the target of stern rebuke from the finance ministers for having chosen to consult its population.

“I am sorry to say that this is no way to get a solution,” commented Schaüble. “I think Yanis that the decision of your cabinet last night was tactically mistaken,” said his Irish counterpart. “If you reverse it you might retrieve some of the situation but we are in a very bad situation now that no matter what happens now there will be a very bad and a very unpredictable outcome.” The Finnish minister said “the news last night was very unpleasant”, while the Slovakian minister commented: “No one around this table is happy with the Greek government’s approach. This is not the first time when [there is] more drama than substance.”

“In these negotiations you became the front-page story, no doubt about that,” the Lithuanian minister sarcastically told Varoufakis. “The worst thing is that [in] many countries you were not only on the front page, in Lithuania you became the last page story. A kind of cartoon.”

For IMF boss Christine Lagarde, the referendum was a “massive surprise and sad development”. Italy’s Pier Carlo Padoan questioned, somewhat scornfully, the capacity of the Greek voters to understand the issues at stake, asking Varoufakis: “May I ask whether you are going to describe measure by measure, alternative by alternative to the Greek people?”

Some appeared genuinely upset that the discussions were being derailed whereas they had had the impression that the Greeks were close to the point of giving more ground and that an agreement would be reached very soon. The discussion ended with the unusual move to exclude Varoufakis, in whose absence a second meeting was to be held in the presence of the remaining 18 ministers and a statement released. He attempted to block such a move earlier in the meeting. “I have a technical question for you,” Varoufakis told Dijsselbloem. “Is it or is it not the case that statements must be agreed to unanimously?” Dijsselbloem replied: “No, if you do not agree we will put this explicitly in the statement, that it is agreed by the 18 ministers and one minister has a different view.”

The statement issued after the second meeting of the Eurogroup that June 27th ended with the phrase: “The statement is adopted by ministers from the euro area Member States, except Greece.”

Varoufakis later asked the Eurogroup secretariat whether such a move was legal. “The Eurogroup is an informal group,” was the reply he received. “Thus it is not bound by Treaties or written regulations. While unanimity is conventionally adhered to, the Eurogroup president is not bound to explicit rules.”

The participants in the negotiations who were contacted by Mediapart and Der Spiegel for this article, including Yanis Varoufakis, all underline that the recordings represent only a part of the history of the Greek debt crisis in 2015. Many things took place elsewhere, before and after the discussions featured here, and during the pauses in the talks. Above all, then Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras and his advisors held parallel negotiations over the head of Varoufakis. The account of the six months, when the existence of alternative economic policies at the heart of Europe were denied, is also the story of the increasing isolation and finally, in July, the departure of a left-field minister – described by some as an eviction, and by others as a resignation.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse