Two Paris-based magistrates leading the investigation into the suspected funding by the late Libyan dictator Muammar Gaddafi of Nicolas Sarkozy’s 2007 presidential election campaign arrived in Libya earlier this month, protected by an escort of an elite French gendarmerie unit, the GIGN, to interview two key witnesses from the former regime.

The February 4th-6th visit to Tripoli was the first time that judges Serge Tournaire and Aude Buresi, who were accompanied by a senior officer from France’s anti-corruption police, the OCLCIFF, had questioned the witnesses face-to-face.

They met with Mohamed Abdulla Senussi, Gaddafi’s brother-in-law who served as the dictator’s intelligence chief and who was sentenced in absentia to life imprisonment by a Paris court in 1999 for his role in the in-flight bombing ten years earlier of a French airliner above the Sahara desert. The other was Al-Baghdadi al-Mahmoudi, who under the Gaddafi regime, which was toppled in 2011, was Secretary of the Libyan General Peoples’ Committee, a post equivalent to prime minister.

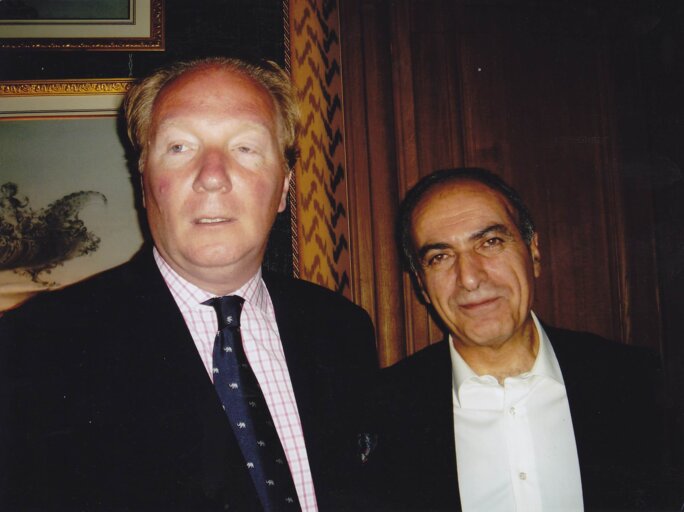

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Mediapart has obtained access to extracts from the statements given to the French judges by Senussi, which are cited in this report. The former Gaddafi spy chief recounted further detail of the alleged Libyan regime’s funding of Sarkozy’s 2007 campaign, from the moment the subject was first raised between him and a representative for Sarkozy, at a seafront restaurant in Tripoli in 2005, up to when he said he oversaw bank transfer payments of 7 million euros in support of the election campaign.

In March 2018, the French magistrates investigating the suspected campaign funding by Libya placed Nicolas Sarkozy under formal investigation (one step short of bringing charges) for “illicit funding of an electoral campaign”, “receiving and embezzling public funds” and “passive corruption”. The alleged "embezzlement of public funds" was in reference to Libyan public funds.

To be “placed under investigation” in France requires that magistrates have found serious and/or concordant evidence that indicates a person has committed an offence.

Sarkozy, 64, has strongly denied any knowledge that his campaign received funding from the Gaddafi regime.

It is unprecedented in France for a former president to face prosecution for having been sponsored by a foreign power.

The magistrates are also in possession of evidence that suggests a deal for the Libyan funding of Sarkozy’s campaign included an agreement to seek the overturning of the arrest warrant issued against Senussi (see more here) for the 1989 bombing of the French UTA airline DC10 plane, in which 170 people lost their lives. The issuing of the warrant prevented Senussi from being able to travel freely abroad.

Both Ziad Takieddine, the intermediary in the contacts between Sarkozy’s political team and the Libyan regime prior to the 2007 elections, and Claude Guéant, Sarkozy’s long-serving chief of staff, have admitted under questioning in the French probe that the subject was discussed between them.

Senussi, who has escaped a death sentence pronounced against him by a Libyan court for his role in the violent suppression of the 2011 uprising, and al-Mahmoudi are currently prisoners of the internationally recognised government based in Tripoli, and were questioned in the company of a Libyan lawyer and a representative of the Tripoli government’s senior public prosecutor.

Senussi, 66, interviewed by the magistrates on February 5th, is reportedly one of the few surviving senior members of the former regime with close knowledge of its darkest secrets, including financial dealings with foreign powers and high-ranking individuals.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

“Nicolas Sarkozy was more the head of a gang than a head of state,” Senussi told the magistrates. “Nicolas Sarkozy attempted to kill me several times, carrying out bombings on my offices, my home, on my houses in the south [editors’ note: of Libya]. The 12 houses were demolished in the space of a minute and a half. I saw a plane without a pilot fall close to me.”

Senussi was referring to air raids carried out by a NATO coalition led by France and Britain during the summer of 2011, when French and British planes were engaged in toppling the Gaddafi regime, with UN Security Council approval, after Gaddafi’s brutal repression of civilian unrest which began in February that year. The war ended in October, when Gaddafi was captured and killed.

At the height of the fighting, in August 2011, news agencies Reuters and AFP reported the aerial bombing of Senussi’s home in Tripoli. Reuters reported that the compound where Senussi’s home was situated was completely destroyed in the early hours of August 19th. At the time, Senussi’s arrest was sought by the International Criminal Court (ICC), along with those of Muammar Gaddafi and his son Saïf al-Islam Gaddafi, for crimes against humanity committed during the uprising.

The August 19th bombing raid killed an Indian cook and also destroyed a local school. “This is a residential district,” a neighbour, Faouzia Ali, told AFP at the time. “Why did NATO bomb this site? There are no military here.”

In September 2012, Senussi, detained in Libya after his capture in Mauritania, was questioned by a member of the ICC prosecution services (which finally ruled in 2013 he should be tried in Libya), when he said he had “personally” supervised the transfer of several million euros by the Gaddafi regime for Sarkozy’s 2007 election campaign. He gave further detail about the transaction under questioning by Libyan judicial officials, acting on the request of the French magistrates, in January 2017.

During the questioning earlier this month, Senussi referred to his earlier testimony, telling the French magistrates: “You have my statements, which are very clear. I maintain them.”

Senussi detailed to judges Tournaire and Buresi an account of several meetings and discussions between the Sarkozy camp and the regime over the funding of the 2007 campaign, up to the point of the payments which he said he supervised, for a total of 7 million euros.

Also placed under investigation in the judges’ probe in France are Sarkozy’s former interior minister and long-serving right-hand man Claude Guéant, who was Sarkozy's 2007 campaign director, along with the campaign treasurer, Éric Woerth (who subsequently served as Sarkozy’s budget – and later, labour – minister, and who is today, as an MP, president of the finance commission of the French lower house, the National Assembly).

Like Sarkozy, both Guéant, who is also accused of personally benefiting from the funds, and Woerth strongly deny the existence of illicit Libyan financing of the 2007 campaign.

Referring to the negotiations to overturn the French warrant issued for his arrest over the 1989 UTA airliner bombing, Senussi told the French magistrates that he was “uncomfortable” about the subject. “Claude Guéant came to see me in [the Libyan port town of] Sirte, he showed me a document […] He told me that my situation in France would be sorted out within six months. I took the document but I did not sign it.”

“The second important thing, is that Nicolas Sarkozy sent his personal lawyer, Thierry Herzog,” he continued. “Thierry Herzog arrived by private plane accompanied by a delegation. He was met by the president of the supreme court, Azza Maghur [who acted as Senussi’s lawyer] and a number of judges. They discussed my situation and agreed on a programme.”

As Mediapart reported last June, Herzog, a friend of Sarkozy’s as well as acting as his personal lawyer, travelled to Tripoli on November 26th 2005 – two months after Sarkozy, then interior minister, paid his first official visit to Libya – when the Paris-based lawyer raised the possibility of annulling the judicial procedure against Senussi. According to four official reports about that visit (three written in Arabic, one in English), Herzog was accompanied on the trip by another French lawyer, Francis Szpiner, who was a legal counsel for Sarkozy’s conservative UMP party. More importantly, Szpiner was also a lawyer for a French association offering support to terrorism victims, SOS Attentats, and also represented the families of victims of the UTA airliner bombing.

When he was placed under investigation in March 2018, Sarkozy denied Herzog’s involvement in contacts with the Libyans and described those witnesses accusing him of accepting Gaddafi’s funding as “an association of thugs and criminals”.

“This Mr Senussi tried using every means to benefit from the skills of Thierry Herzog who, beyond his very great competence, is close to me, even going to the extent of sending him in 2008 [in fact, 2006] a mandate to represent him,” Sarkozy told the magistrates. “This mandate was put in the paper bin by Mr Herzog, who refused to make the slightest move or consultation in his favour.”

A vast bank safe rented 'to store Sarkozy's speeches'

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Libyan lawyer Azza Maghur has confirmed to the French investigation the nature of her discussions with Herzog and Szpiner. Questioned by the French investigators in Paris on December 12th last year, Herzog refused to answer questions on the subject, citing his obligation of professional confidentiality and “in order not to impede on the rights of defence of Mr Nicolas Sarkozy”.

Early last October, Szpiner initially refused to appear before the magistrates, as summoned, for questioning. Instead, he sent them a letter in which he denied travelling to Libya in 2005. After the insistence of the magistrates that he appear before them, Szpiner was questioned on October 22nd, when he categorically denied making any move to help Senussi, despite concordant witness statements and documents in the judges’ possession that he did so.

During his questioning on February 5th, Senussi told the magistrates that Herzog’s involvement in his case was “the proof” of the Libyan financing of Sarkozy’s campaign. “If they sent me their lawyer, it wasn’t because of my pretty face,” said Senussi in his statement. “I took Mr Herzog as lawyer at the request of Nicolas Sarkozy, because he was confident in him.”

Recalling the chronology of the discussions about the funding, he said the subject was discussed during a visit to Tripoli by Claude Guéant – then Sarkozy’s ministerial chief of staff – in September 2005: “We dined together in a restaurant at [the Tripoli coastal neighbourhood of] Gargaresh. We discussed the fact that we were ready to support Mr Nicolas Sarkozy so that he might attain the French presidency. During this discussion, we agreed that France would supply Libya, via a company specialised in security, equipment to listen and monitor internet traffic and all communications. These instruments still exist because the security services currently use them.”

This was a reference to a deal agreed with French firm Amesys, as Mediapart first reported in 2011, for which the Paris-based intermediary for Sarkozy’s team, Ziad Takieddine, received commission payments of more than 4 million euros.

Sarkozy travelled to Libya in 2005 shortly after that visit by Guéant, and, according to Senussi, “He was treated like a head of state”. Senussi repeated his earlier affirmation that he spoke to Sarkozy by phone during the latter’s visit. “He contacted me through the intermediation of Ziad Takieddine, from the hotel Corinthia, to say that he was waiting for me on the 15th floor in his suite.” But Senussi, according to his own account, warned Sarkozy that a “direct meeting” could have unwanted consequences given that he was “a suspect in France”. Much more, in fact, than a suspect, Senussi was a fugitive convicted for his part in the mass murder committed against the 170 passengers of the UTA airliner.

Senussi said that after Sarkozy’s visit, Takieddine transmitted a “request” for 20 million euros, although the amount he was personally involved in overseeing payment of was, he said, 7 million euros. In a previous statement he gave to Libyan judicial officials in January 2017, who were then questioning him on behalf, and at the request, of the French magistrates, Senussi said of the 7 million euros: “This sum was effectively transferred in several [payments] by the Libyan foreign Bank on the instructions of the Libyan central bank and at the request of the intelligence services’ directorate. The funds came from accounts held by the intelligence services’ directorate at the Libyan central bank, on the orders of Mr Ahmed Ramdane, secretary of the presidency […] for the payment of the sum of 7 million euros into the account of the military intelligence directorate, for the financing of support for the Sarkozy campaign, on the order of Muammar Gaddafi.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

According to Senussi, it was Brice Hortefeux, one of Sarkozy’s most faithful friends and longest-serving political allies who, during a visit to Tripoli, gave Senussi “a piece of paper on which was written the name of a bank and an account number”. Senussi said Hortefeux told him “that it was the account into which should be sent the money paid [by Libya] in support of Sarkozy’s electoral campaign”.

“I kept a photo of this detail, a copy at my home, but the bombings that destroyed my house demolished everything,” Senussi said in his statement to the French judges on February 5th.

In his 2017 statement, Senussi said that once the money had been successfully transferred, Takieddine informed him that he had “personally proceeded with the delivery of the money in cash to Nicolas Sarkozy, in his office, in several instalments”. Takieddine himself has said he personally transported and delivered, in cash placed in suitcases, 5 million euros to Claude Guéant and Nicolas Sarkozy, between the end of 2006 and the beginning of 2007.

The French investigation has found trace of a bank transfer of 2 million euros from Libya into an account managed by Takieddine, dated November 20th 2006. Coupled to the 5 million euros Takieddine says he delivered to Sarkozy and Guéant, the total of 7 million euros corresponds with the amount Senussi claims he oversaw payment of.

Two important details on the subject remain unclear. One is that Senussi recalls his meeting with Brice Hortefeux as being in November 2006, whereas Hortefeux (who also served as interior minister, before Guéant, in Sarkozy’s government) says he met Senussi in December 2005. The secret meeting between the two men – which is, despite the confusion about the date, established, and for which there was no obvious official reason for it to take place, given that Hortefeux was at the time a junior minister in charge of policy planning for France's local authorities – took place in the presence of Takieddine but without any involvement of French diplomatic staff, security officers or translators.

The other issue to be clarified is Takieddine’s claim that he transported the cash he says he gave Sarkozy from Libya, rather than from a foreign bank. Senussi, meanwhile, has said he was not aware of all the “technical details” of the operation.

The French investigation has established that Claude Guéant, campaign director of Sarkozy’s 2007 election bid, secretly rented, also in 2007, a vast safe deposit room from a branch of the BNP bank in Paris solely for the duration of the election campaign. During questioning by anti-corruption police, he gave a surprising explanation that the walk-in safe room, big enough for an adult to stand upright in, was rented as a place to store texts of Sarkozy’s speeches.

Statements from staff who worked for Sarkozy’s 2007 election campaign have referred to an abundance of cash used for payments. In their summary of statements given to them by the campaign treasurer, Éric Woerth, French anti-corruption police have described his explanation of the presence of the cash sums (which he suggested in part may have come from cash donations spontaneously sent through the post by Sarkozy supporters) as being unconvincing.

Senussi has claimed that other former ranking members of the Gaddafi regime, and notably Bashir Saleh, Gaddafi’s cabinet chief and head of the regime’s multi-billion-dollar Libyan African Portfolio sovereign wealth investment fund, also provided separate, parallel funding to Sarkozy’s team. “I know that Bashir Saleh gave 8 million euros to Claude Guéant to finance the campaign,” he told the French judges during his questioning in Tripoli this month. “I heard this directly from Bashir Saleh.”

Interviewed last year by French public broadcaster France 2 in its flagship current affairs programme “Cash Investigation”, Saleh, who estimated that the Gaddafi regime put aside a slush fund of around 350 million euros for foreign corruption operations, finally recognised the existence of Libyan involvement in Sarkozy's 2007 campaign, but gave no detail of the funding support.

According to Senussi’s statement this month, the funding Saleh was allegedly in charge of was transferred via the intermediation of “common Algerian friends”, who were known to both Saleh and Gaddafi’s son Saïf al-Islam Gaddafi. In his testimony given to Libyan officials in January 2017, Senussi said Saleh “had close relations with a group of contacts, among whom was a person of Algerian nationality linked to [former French president, Jacques] Chirac and his advisors”.

In both statements, he appears to designate Alexandre Djouhri, who is wanted by the French investigation for his suspected misuse of public funds, money laundering and laundering the proceeds of tax evasion. He is notably suspected of playing a key role in financial set-ups that benefited Guéant and also in helping Saleh flee from France in 2012, when the latter faced imminent arrest after featuring on an Interpol ‘wanted’ list.

Djouhri is currently resisting extradition to France from Britain, after he was arrested in London in January last year at the request of the French authorities.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse