On January 20th 2014, Nelio Lucas celebrated his 35th birthday in lavish manner. Close to his offices in central London, in a former 19th-century church in the plush area of Mayfair, Lucas hosted 118 guests in evening dress for a dinner and dance party that lasted into the early hours. The cost of the evening came to 195,000 euros, which he settled from his account in Lichtenstein.

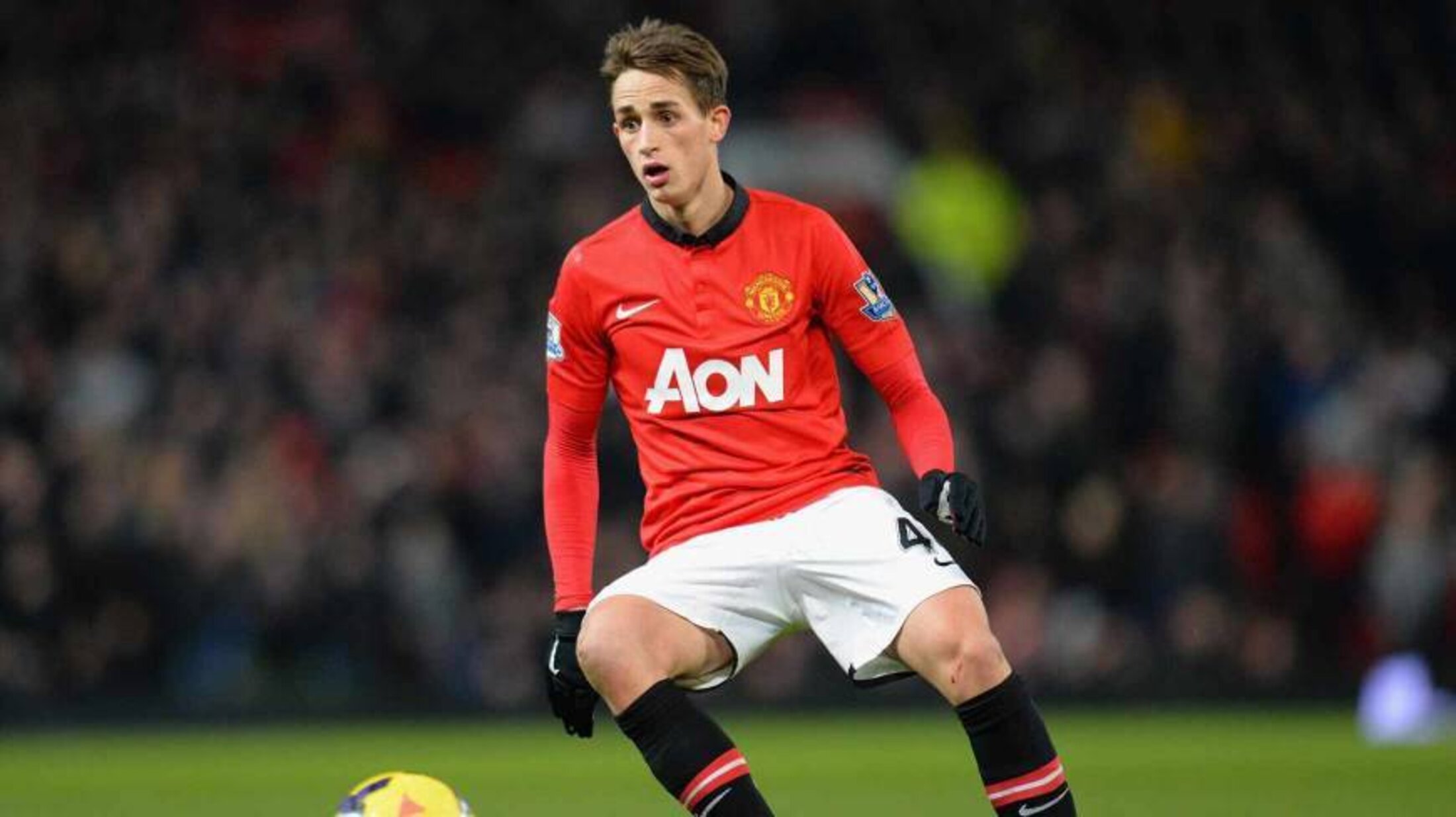

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The event, to which were invited friends and business partners, was more a demonstration of strength than a birthday party. Present were Real Madrid president Florentino Perez and Miguel Angel Gil, CEO of Atlético de Madrid, who put aside their sporting rivalry to toast Lucas’s good health. Also attending the event were A.C. Milan vice-president Adriano Galliani and his daughter, who Lucas’s company Doyen Sports Investments had recently hired, Inter Milan’s sporting director as well as the directors of English club Fulham, Portuguese side Sporting and Spanish club Sevilla, and also the son of the president of Portuguese club Porto.

Members of football’s elite sat alongside oligarchs from the former Soviet Union (the owners of Doyen Sports), Swiss tax lawyers specialized in offshore structures, and intermediaries like the former agent Luciano d’Onofrio, who continues his activities, notably with doyen Sports, despite a criminal record for corruption (see our investigation here). Players managed by Lucas’s business were also at the party, including Barcelona forward Neymar, his then team-mate Xavi Hernández, and Chelsea defender David Luiz.

Nelio Lucas had good reason to feel pleased with himself. In the space of less than three years, this businessman unknown to the wider public had steered Doyen Sports Investment into becoming one of the biggest investment funds in European football. The media had even begun to compare him to the leading football agent Jorge Mendes, also Portuguese. An advisor to clubs, who also acted as an agent and intermediary, Lucas manages the marketing of football superstars David Beckham and Neymar, the Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt, and the AS Monaco football club.

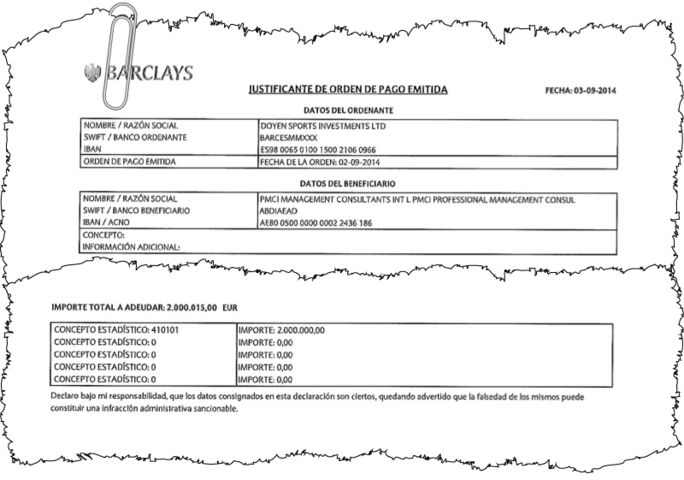

Enlargement : Illustration 2

But the speciality of Doyen Sports was the trade in Third-Party Ownership (TPO) of footballers, a decried system whereby a player’s economic rights are owned in stakes by investors. These could be made by individuals, companies or funds, who were then subsequently entitled to a proportionate part of the player’s future transfer fee. Doyen had invested more than 100 million euros in TPO deals up until the practice was outlawed by football’s governing body, Fifa - whose president Gianni Infantino likened the system to “modern slavery” - in May 2015.

Documents from the whistle-blowing platform Football Leaks, obtained by German weekly news magazine Der Spiegel, and transferred to the journalistic collective European Investigative Collaborations (EIC), in which Mediapart is a founding partner, reveal, for the first time, the dark side of Doyen Sports, where feature shell companies in Malta and the United Arab Emirates, vast secret commissions to assist with player transfers, false billing, contracts signed by frontmen and conflicts of interest.

Contacted by Der Spiegel magazine on behalf of the EIC, Nelio Lucas refused to answer our questions. Instead, the EIC was contacted by Harbottle & Lewis, the London law firm that represents the interests of Doyen Sports, which said its clients took issue with all of the matters raised by the EIC. The legal practice warned that its clients would consider taking legal action if we were to publish the information in question. Harbottle & Lewis said this was obtained through an illegal cyber attack followed by a blackmail attempt which was being investigated in Spain and Portugal.

Doyen Sports is the symbol of a reality far removed from what goes on on the pitch. It is that of a transfer business resembling a cattle market, except that its yearly value reaches 4 billion euros. It is a trade where scruples have long been jettisoned in the quest for riches.

The story of Doyen Sports begins with an improbable encounter between Nelio Lucas, the son of a Portuguese family of modest means, and Arif Efendi Arif, the son of a Kazakh businessman.

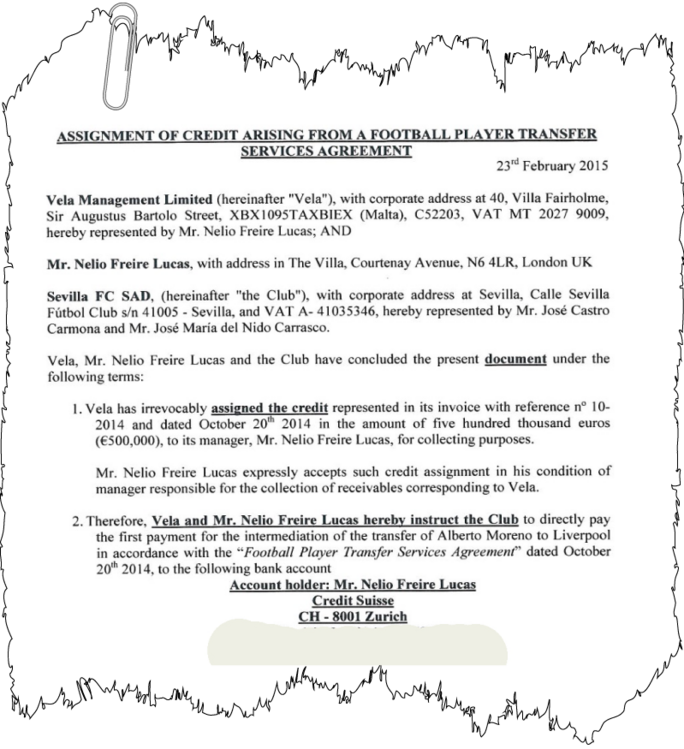

Enlargement : Illustration 3

In an interview with French daily Libération in October 2015, Lucas said he had studied marketing communication and international politics at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). But contacted by the EIC, UCLA said Lucas had never been enrolled at the university. In the same interview with Libération, he claimed he later joined a US agency representing showbusiness stars. “I looked after Mariah Carey, I’ve been road manager for Bruce Springsteen,” he told the daily.

In the early 2000s he returned to Europe, where he managed a modelling agency and was convicted and fined for tax evasion, driving without a licence and issuing cheques with no provisions on his account. In London he began working for a successful Israeli football agent, Pini Zahavi, who taught him the trade, before the two men eventually fell out. In 2011, Lucas was hired to launch Doyen Sports.

The owners of Doyen Sports Investment are four brothers from Kazakhstan who are now based in the Turkish city of Istanbul, and who made their fortune notably in the business of raw materials. In 2011, the Arif brothers created a London branch of their group, which was renamed Doyen, including a sports division. Arif Efendi Arif, the then 25-year-old son of Tevfik Arif, one of the four brothers, was given the job of managing the London business, running the newly-created Doyen Sports alongside Nelio Lucas.

Lucas and Arif appeared to get on well together, both ambitious and hungry to make money. “Imagine us in 10 years. Inshallah kings,”Arif wrote to Lucas. “Don’t forget our lemma: together forever on good and bad. We will succeed and we will become billionaires,” Lucas told Arif.

The two young men travelled together to football matches, to plush London restaurants and enjoyed trips to Ibiza, Italy and the French Riviera where they stayed in the luxury villa of the Arif family in Antibes. In 2013, Arif Arif went househunting in London. “Found a real nice one,” he told Lucas. “Want to show you. Tailor made for orgies.” To which Lucas replied: “Oh yes !!!”

At Halloween, Lucas was dithering between wearing a disguise as a pope, Napoleon or Louis XV. “For me the dictator,” Arif told him.

In an exchange of text messages on WhatsApp in 2014, Arif listed to Lucas his player clients taking part in that year’s World Cup in Brazil. “Mangala, Promes, Defour, Januzaj, Xavi, Falcao, Rojo, Negredo, de Gea… Doyen Sports niggas going to World Cup! ” When Neymar’s Brazil team qualified for the semi-finals, Arif wrote to Lucas: “Neymar bitch. Nigga making us money.”

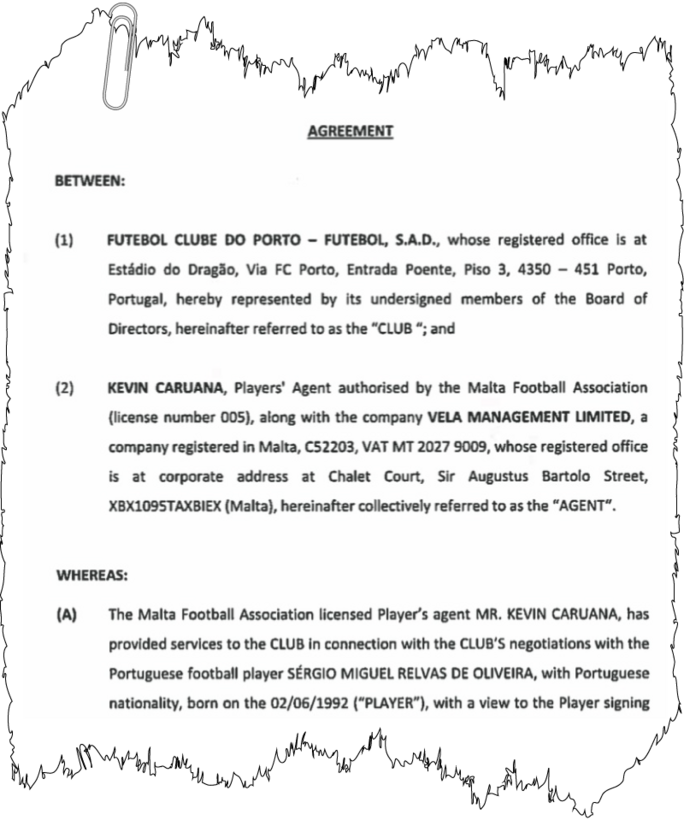

Enlargement : Illustration 4

The comments about players turned notably unpleasant if a footballer chose his own interests before those of Doyen Sports. One such case was that of Moroccan player Abdel Barrada, in who Doyen Sports had a 60% TPO stake. In 2013, the midfielder left Getafe, a club close to Madrid, for United Arab Emirates side Al-Jazira. It appeared that for Lucas, the 3.35 million euros that Doyen received from the transfer – equivalent to twice it paid for its TPO stake two years earlier – was a disappointment. He wrote to Arif: “We couldn’t control him more. […] If the player had listen to me I will get more”, and insulted the player over his religion.

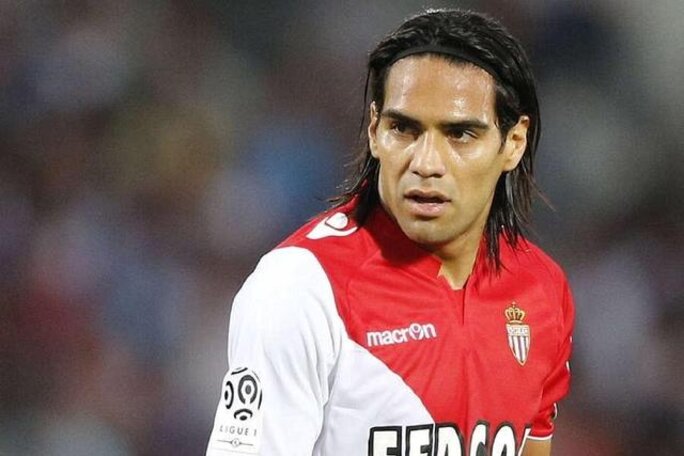

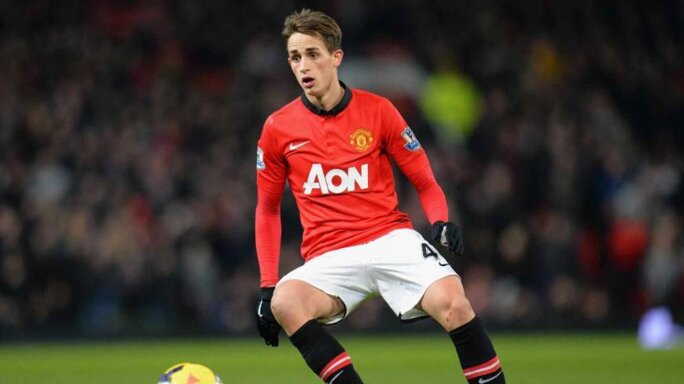

It was a similar story with Colombian striker Radamel Falco who, also in the summer of 2013, moved from Atlético Madrid to Monaco, a transfer managed by his agent Jorge Mendes. The transfer fee was 43 million euros, which earned Doyen, which had a 33% stake in the player, a profit of 5.3 million euros. But Lucas had apparently hoped for greater returns from Falcao. “He went to Monaco that fuck,” he wrote Arif, before insulting the Colombian player’s mother and concluding: “His career is finished. […] He will end up paying taxes in France.”

Enlargement : Illustration 5

For Doyen Sports Investment, it would appear that “tax” is an unpleasant word. The company is based in Malta, giving it a respectable European Union base while also offering the attraction of a clement tax regime and business secrecy. Nelio Lucas owns two offshore companies registered in the Mediterranean archipelago, hidden behind front names. One of them is WGP, which holds a 20% in Doyen Sports which was offered to him by the Arif family. The second, called Vela and which has a bank account in Liechtenstein, handles the yearly 900,000 euros that remunerate Lucas and his colleagues. The Portuguese also has an account with the Crédit Suisse bank in Zurich. The reason, he explained, was “in order for nobody to disclose nothing about us”.

Nelio Lucas was also offered a 20% stake in Doyen Natural Resources, one of the group’s Panama companies which it owns via a shell company in the British Virgin Islands. When he was not buying into footballers, Lucas travelled to negotiate mining deals in Brazil, Sierra Leone and Angola, three countries steeped in corruption. “Do you thing I should bribe them???” he asked Arif in one message about his dealings in Brazil. “Yes bro,” came the reply. The business deal collapsed, apparently after the other party tried to bribe Lucas.

But the speciality of Lucas was above all TPO deals. Doyen Sports acted like a sort of usurer in the world of football, obtaining prohibitive interest rates for clubs in financial crisis. The system was that Doyen Sports would buy from a club a stake in a player, in the hope that he would rapidly be sold on at a good profit for Doyen Sports, which received a proportionate share of the transfer fee paid by the new club. Officially, Doyen Sports has no influence over transfer decisions, as stipulated in Fifa rules. But in practice things were otherwise.

For Doyen Sports, many means were used to clinch a deal. In August 2013, Lucas planned a bunga-bunga style party in Miami in the hope of convincing Real Madrid boss Florentino Perez to buy French midfielder Geoffrey Kondogbia in which Doyen Sports had invested a stake. Contacted by the EIC, Perez strenuously denied ever taking part in the party.

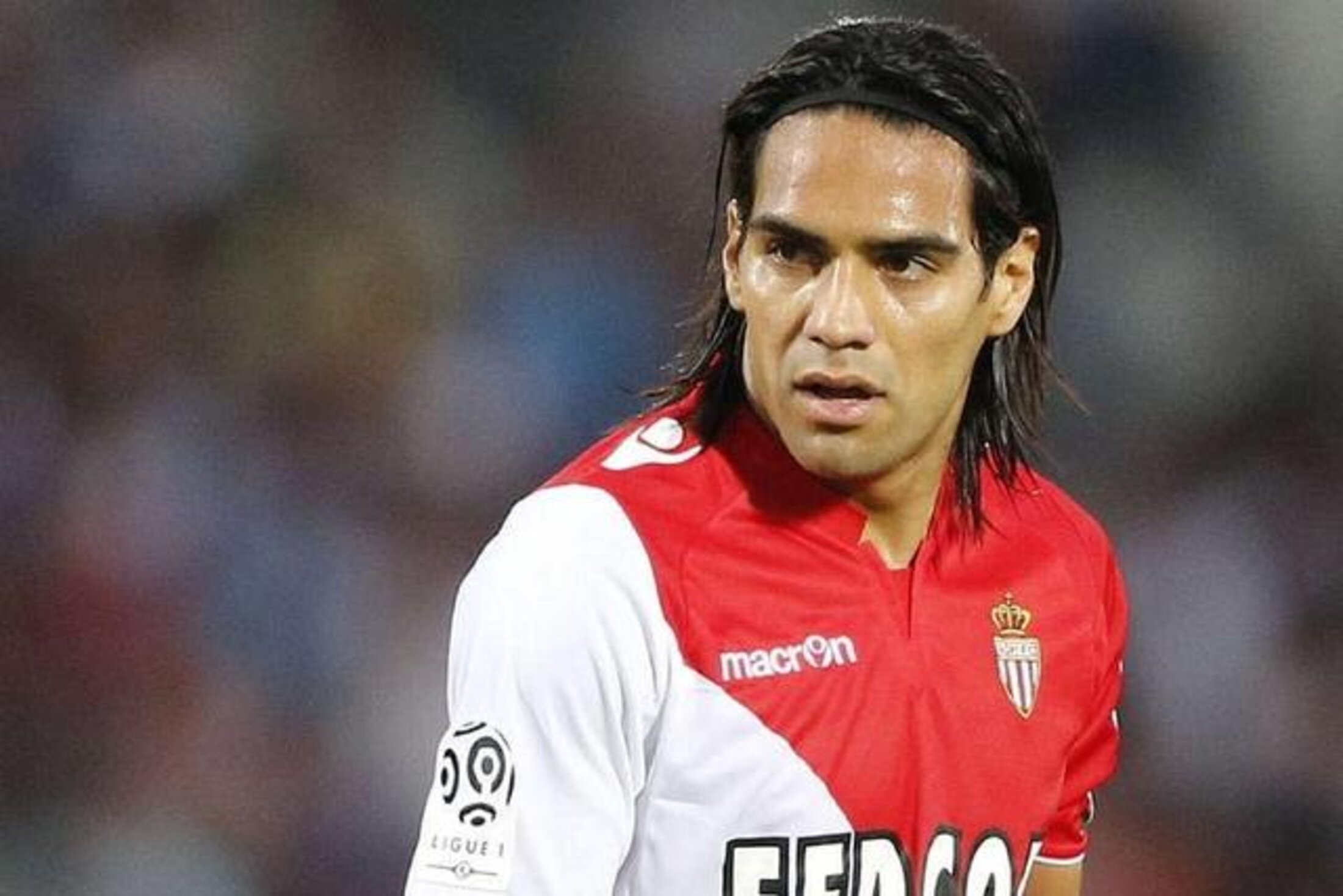

On 14 occasions between March 2014 and September 2015, Lucas shuttled around pretty young women from Minsk, Moscow and Saint Petersburg to help with business deals. The plane tickets were paid by his offshore company Vela. Some of the women were models. Another, whose first name is Kateryna, boasts on her Twitter account that she is a “Beautiful woman - a paradise for the eyes, hell for the mind and purgatory for the pockets”.

Excepting the case of two women brought to Ibiza for two days of partying, Lucas used the female company exclusively on business trips. On April 9th 2014, he flew to Madrid Kateryna, who travelled from Moscow, and Vladyslava, who came from St. Petersburg. That date corresponded exactly with the Champions League quarter-final between Atlético Madrid and Barcelona.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Women from Eastern Europe also accompanied him on business trips to Madrid, Barcelona, Brussels and Athens. On August 26th 2015, Lucas travelled to Madrid with a blonde-haired woman called Sabina for the signing of the transfer of Spanish midfielder Asier Illarramendi from Real Madrid to Real Sociedad. Five days later, Sabina travelled with Lucas and the Costa Rican forward Rolando Fonseca to Marseille, to where he was to be transferred from Portuguese club Porto. Contacted by the EIC, Sabina insisted that her relationship with Nelio Lucas was one of friendship, and that she had never worked for him.

Meanwhile, the subject of prostitutes is openly discussed by the two Doyen Sports directors: “It would be nice if you can get me those 2500 GBP, I paid the bitches!!!” wrote Lucas to Arif in July 2013.

There is of course nothing illegal in associating with prostitutes. But Arif Arif appears keen to bring them from Eastern Europe, via two intermediaries, one of whom is a cousin. In exchanges on the subject, he carefully uses the words “footballers” and “players”, as in this message: “Organise footballers now. Don't fucking waste time, we're gonna end up like last night with nothing!!!!” That was replied to three hours later with a photo of one woman. The intermediary informs him that he is going to take part in a “big casting this weekend”organised by Russian gas-producing giant Gazprom.

Contacted by the EIC, Arif Arif refused to comment on whether he used his network to find the women who accompanied Lucas in his business dealings.

As of the autumn of 2013, Nelio Lucas decided to use funds hidden in three shell companies based in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), including the capital Abu Dhabi and Ras al-Khaimah. Doyen Sports was to pump 10.8 million euros of secret commissions into the companies, called Denos, Rixos and PMCI. The documents contained in the Football Leaks files do not reveal to who the money was ultimately destined.

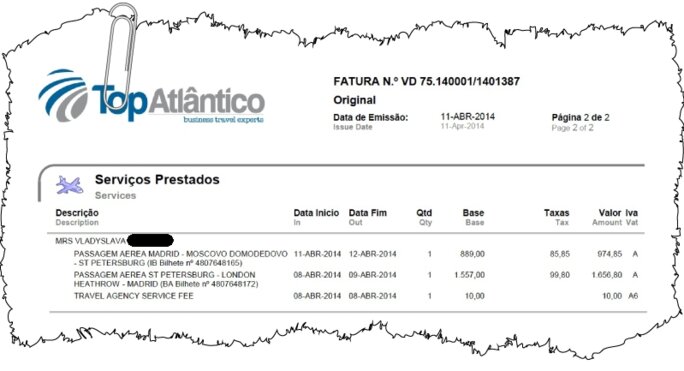

The first of the major deals concerned commissions surrounding Belgian international and Manchester United winger Adnan Januzaj, now on loan to Sunderland. In February 2014, Doyen Sports bought half of the company that managed Januzaj’s image rights for 1.5 million euros, and then made a second payment of 500,000 euros that transited via Denos with a false “consulting” contract and a false invoice.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

In an email sent by Lucas, this was described as “pay Januzaj". On May 22nd 2014, a lawyer representing Januzaj’s agent wrote to a female colleague of Lucas to complain that the payment had not yet been made, and that the player’s father was becoming agitated.

Adnan Januzaj did not respond to the EIC’s attempts to interview him.

In the summer of 2014, the system became more frequently used. Lucas demanded that 10% of profits from each player transfer should be paid into Denos in the UAE. The first secret commission payment, of 1.3 million euros, concerned the sale to Monaco in the summer of 2013 of French midfielder Geoffrey Kondogbia and also the Colombian striker Radamel Falcao.

Lucas would explain that the transfer was to pay “people that we need to compensate” and who “could not provide or didn't want to provide paperwork”. He added that he had promised the recipients this but that they were losing patience while waiting to receive the payments. “We can't delay more,” he wrote. “It's costing us other deals and is destroying my good name.” Arif Arif had wanted to know more about the identities of the recipients but his father, Tevfik Arif, one of the four brothers who control the Doyen group, told him “to stay out of it”. When the group’s accountants made known their concern that no contracts were submitted, Arif Arif nevertheless allowed the payment to go ahead.

In August 2014, English club Manchester City bought French central defender Eliaquim Mangala from Portuguese club Porto for 45 million euros, which was an all-time record for a defender. It would also provide Doyen Sports with its most profitable return on a TPO investment. With a 33% stake in Mangala, Doyen Sports earned 10 million euros in the deal, which was four times the price it paid for the stake in the player.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

Then, on September 2nd, just five days after receiving the money, Lucas wrote to Doyen’s banker to arrange that 2 million euros be transferred on to shell company PMCI in Abu Dhabi. That represented 20% of the profit made on the transfer of Eliaquim Mangala - twice the usual 10% that was siphoned off abroad. As justification for the bank transfer, Lucas sent to the Doyen banker an unsigned contract according to which PMCI had carried out consultancy work for Mangala’s transfer. Once more, the beneficiary of the sum remains a mystery.

Enlargement : Illustration 9

Franco-Algerian midfielder Yacine Brahimi grew up in France and began his senior career with Rennes before later moving on loan to Spanish club Granada in 2012, signing a permanent deal with the Spaniards in 2013. In the summer of 2014, Portuguese side Porto announced that it had bought the player for 6.5 million euros. In reality, Brahimi cost the Portuguese 9.5 million euros, of which 8 million euros was paid for by Doyen Sports in exchange for an 80% stake in the player.

Lucas explained that Doyen Sports had in all secrecy bought up the stake in Brahimi of another investor, thus avoiding a commission payment for Rennes which had negotiated “a share in the profit of the future transfer”. Porto paid a commission of 500,000 euros into the account of Doyen Sports shell company Denos, in Dubai. It was Lucas’s colleague Juan Manuel Lopez who signed the contract papers, possibly because Lucas did not have an agent’s licence.

Enlargement : Illustration 10

The following year, on July 29th 2015, Lucas ordered a secret payment of 1.5 million euros for Brahimi, via Denos. “Brahimi is our priority even because it might happen a deal this summer!” wrote Lucas. The nature of the deal was unclear but Lucas was impatient to see the matter settled. “Is this paid?” he wrote a few days later, on August 4th. “Need that swift today […] Player wants to speak with club and will be embarrassing for me.”

The money was finally transferred on August 10th. One month later, Brahimi successfully renegotiated his contract with Porto and which included the sale to the club of his image rights, for 4 million euros. Porto paid Lucas a commission payment of 500,000 euros for his assistance with the negotiations, which was sent into the Liechtenstein bank account of Lucas’s Maltese-registered company Vela.

Vela was also given a mandate for the future sale of Brahimi, along with a 10% commission on whatever sum that would be for. It was a quite extraordinary situation given that Lucas headed Doyen Sports which itself owned an 80% stake in Brahimi.

Neither Brahimi nor Porto agreed to answer the EIC’s questions.

It was not the only example of how Lucas would do business in his own name as well as that of Doyen Sports, using his shell company Vela in which his name is never apparent. Because he did not have a Fifa agent’s licence, which was necessary until 2015, he used front men. Lucas had three business colleagues who in parallel worked as football agents, and who he involved in some of the deals.

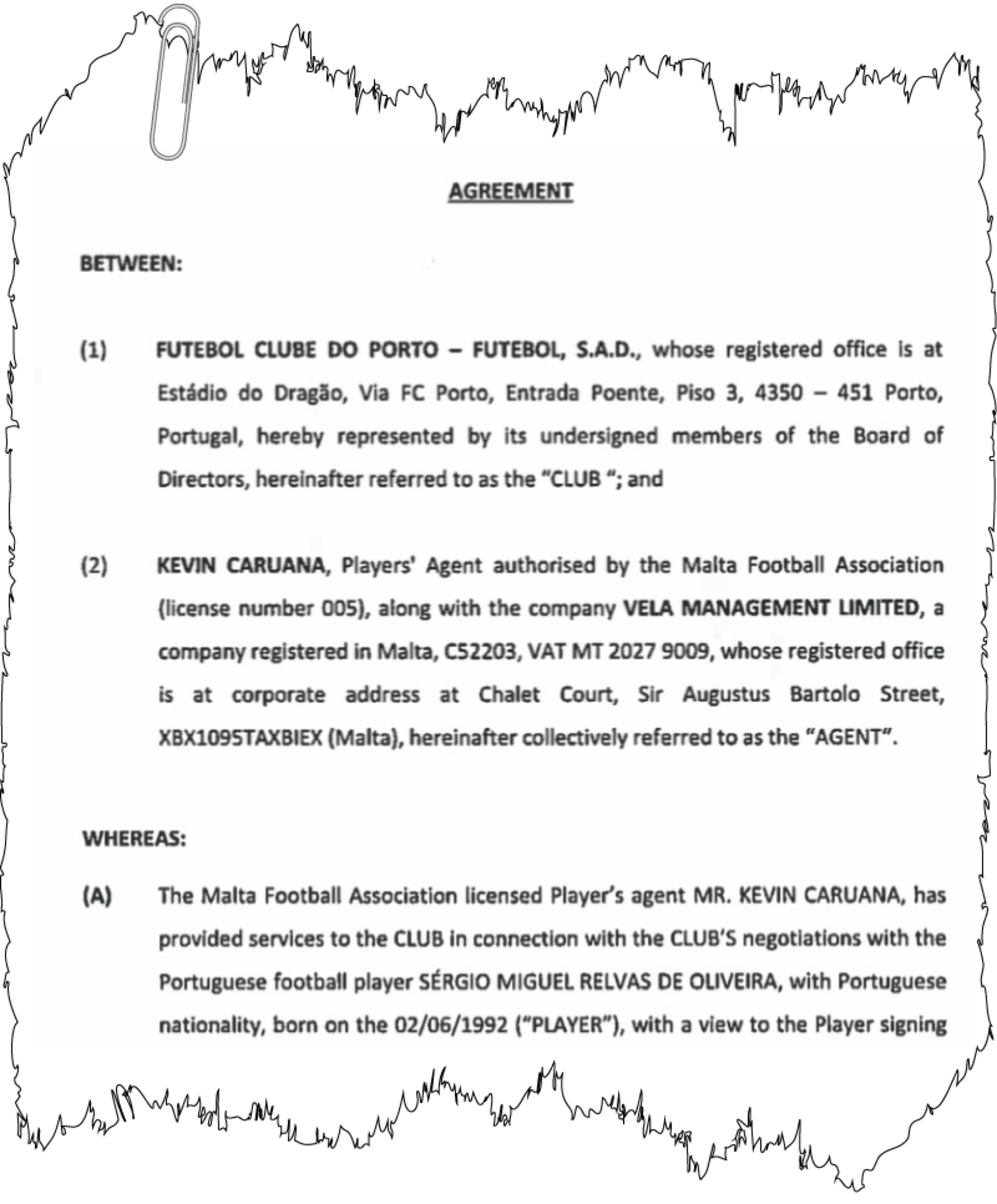

On August 20th 2014, Maltese Fifa-licensed football agent Kevin Caruana, now working on the island in the financial sector, wrote to Doyen Sports to propose his professional services after he had seen the company was registered in Malta. His proposition arrived with perfect timing, for Lucas was on the point of receiving a 1.6-million-euro commission for his role in the transfer of Spanish defender Alberto Moreno from Spanish side Sevilla to English club Liverpool. Lucas needed a frontman agent to sign the contract on Vela’s behalf.

Lucas’s lawyer was concerned about involving Caruana, who was unknown, had never taken part in the operation. Lucas was under pressure to sign the contract himself. But Sevilla refused to pay the commission into Vela’s Liechtenstein account because the Spanish tax authorities had black-listed the principality. Lucas’s advisors tried to open an account elsewhere, but they reported that the first bank they approached had refused to become involved after consulting the documents they presented.

Lucas concluded that he would have to use his Swiss bank account with Crédit Suisse, but he was concerned. “But what will be the tax implication for me?” he asked, in a message to his Swiss financial affairs advisor who managed Lucas’s offshore structures. “Also not sure if good idea to disclose my account,” he added. The expert replied that he did not envisage problems as long as the money stayed in Switzerland. “Obviously if you use the money from your account […] it will be difficult to argue towards the tax authorities that it is not your money,” warned the expert.

Enlargement : Illustration 11

But even comparatively minor profit was not to be overlooked. Porto defender Sergio de Oliveira was released on a free transfer by his club to move to a modest Portuguese side. Porto retained a 50% stake in the player’s economic rights. But in January 2015, shortly after Doyen Sports had begun representing the player, Porto decided to ask him back - with Doyen Sport’s financial help. The process was steeped in a conflict of interests, because Doyen Sports was Sergio de Oliveira’s agent, also holding a 25% stake in the player which it had bought for 500,000 euros from Porto, while Lucas was paid a 300,000-euro commission as agent for Porto.

Because Portuguese law prohibits a person or company from representing more than one party in a transfer deal, Lucas turned to the Maltese Kevin Caruana who signed the contract for the 300,000-euro commission on behalf of Vela. Caruana was paid 2,000 euros for his services. Shortly afterwards, Caruana wrote to Lucas to ask him to “introduce me to the Porto people”, the very same people he was officially supposed to have done business with in the Sergio de Oliveira deal.

Enlargement : Illustration 12

Lucas’s wealth and contacts opened doors even in countries where the practice of TPO had always been outlawed, such as in France. Doyen Sports enjoyed a good working relationship with Monaco, which in 2014 gave it the mission of finding new marketing contracts for the club in exchange for a 10% commission on the deals. Lucas also had excellent relations with Vincent Labrune, who from 2011 until July this year was president of Marseille football club. “In 2014, I had many meetings with [French] League 1 clubs,” Lucas told French daily Libération in October last year. “They came to me to find solutions. I hear [Lyon] chairman Jean-Michel Aulas criticised investment funds. But Lyon is one of those clubs […] Vincent Ponsot [Lyon club director] sent me a thousand messages to tell me that Aulas wanted to meet me.”

Fifa’s move to ban TPO deals would finally become effective in May 2015. “These cocksuckers want to bash third party ownership continually,” wrote Arif Arif of journalists critical of the TPO system. In November 2014, one month before Fifa representatives were to vote on the proposition to ban TPO deals, there was a rush of activity at Doyen Sports. Lucas sent a note out to his staff listing three players, one Brazilian and two Spanish, in who he wanted to buy a stake. “It’s now coming a moment that will affect badly our business as deals as we been doing are probably going to be forbidden,” he wrote. “[…] So we should focus in make new deals now, THE MAXIMUM WE CAN.”

After the Fifa ban was introduced in May 2015, which allowed for a transitional period, Lucas attempted in vain to buy on his personal account 25% of French midfielder Gilbert Imbula during the latter’s transfer from Marseille to Porto.

Doyen Sports, meanwhile, tried buying into players in lower divisions. In November 2015 six months after the Fifa ban came into effect, Doyen Sports bought stakes in all the players with Spanish second division side Cadix, for a total cost of 1.5 million euros. The partners to the deal agreed a clause by which the sale of the stakes purchased would be validated only if and when the Fifa ban was overturned. Until then, the money that was paid served as a loan.

Because only clubs are now allowed to hold a stake in players, Lucas attempted to buy a stake in Spanish club Granada via a company in the Netherlands. “I have to close urgently with Granada and I need the structure,” Lucas wrote to his lawyers on July 15th 2015. In the end, the Spanish club preferred to sign a deal with Chinese investors.

Lucas also became involved with a protracted attempt by Thai financier Bee Taechaubol to invest in Italian club A.C. Milan. After months of talks, in May 2015 Taechaubol appeared on the cusp of buying out 48% owned by former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi’s Fininvest company. Taechaubol appointed Doyen Sports as an advisor for the deal. It appears likely that Doyen Sports’ involvement was the result of Lucas’s friendship with Adriano Galliani, the club’s vice-president, and whose daughter was employed by Doyen Sports.

On June 10th 2015, Taechaubol published a photo on his Instagram account showing Lucas and Galliani shaking hands in a private jet, alongside the caption: “Building together under the guidance of the President.” But the deal eventually fell through. For while Bee Taechaubol insisted he remained in the bidding, Berlusconi this summer agreed to sell the club to a Chinese investment group in a deal yet to be finalised.

-------------------------

- This article in English is based on Mediapart's original report in French, which can be found here.