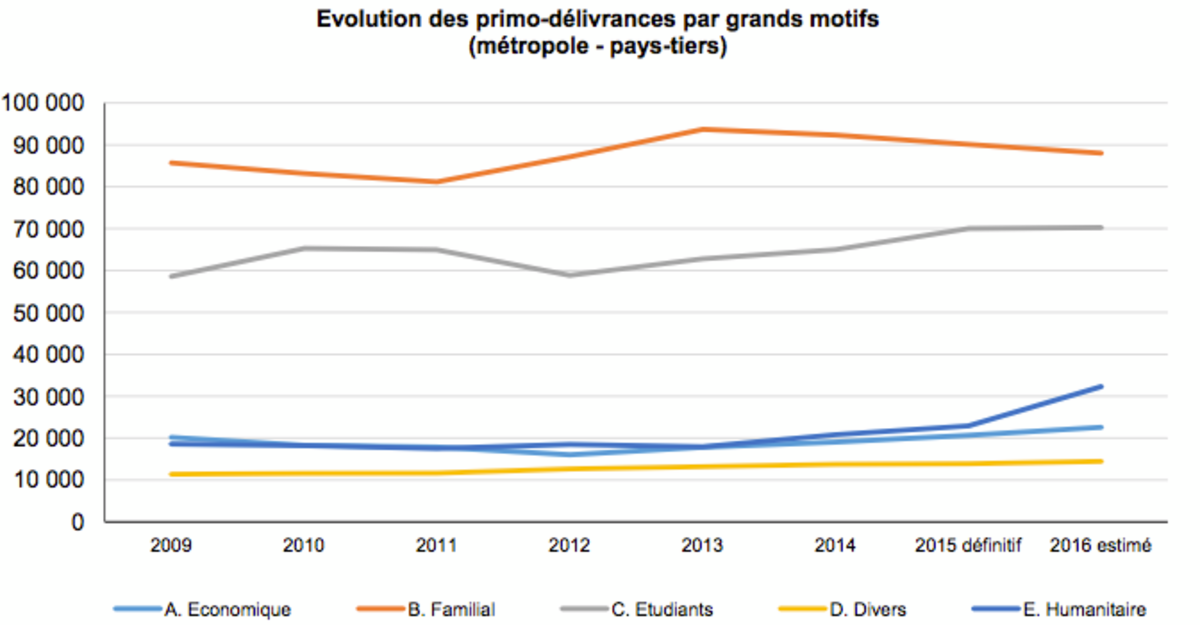

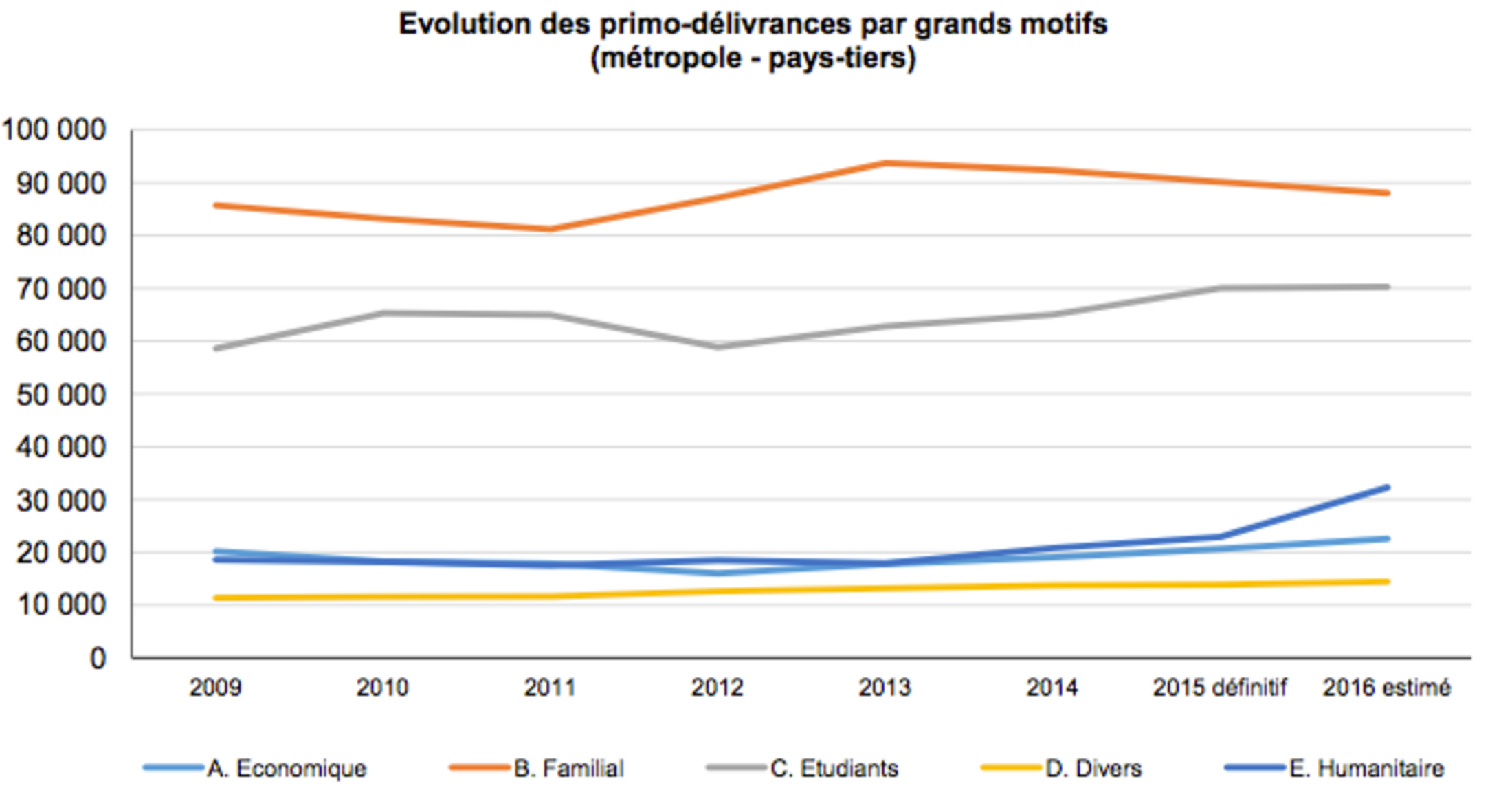

Figures released this week by the French interior ministry, and which exclude nationals from European Union (EU) countries who are free to live and work across the bloc with no restrictions, showed that in 2016 a total of 227,500 people obtained for the first time a French residency permit.

That number was a 4.6% rise on 2015, when residency permits were granted to 217,533 people.

The interior ministry, basing its calculations on data from the different prefectures spread around France (foreign nationals apply to that which is geographically nearest to them), found that 22, 575 foreign nationals declared they had arrived in France for economic reasons, a rise of 9.4% on 2015. Another 32,285 had come for humanitarian reasons, representing a rise of 41% on 2015, while 88,010 others had come to rejoin their families, a total that was down by -2.3% on 2015.

The number of foreign students arriving in 2016 was 70, 250, up by 0.3% on the previous year, and 14,430 other foreign nationals had come to France for various other reasons, including long-stay visits.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The total year-on-year rise in the numbers seeking legal residency in 2016 is therefore mainly due to those seeking protection under the status of refugee, reflecting the massive flow into Europe beginning in 2015 of hundreds of thousands of people fleeing Middle East conflicts and repression in the Horn of Africa.

The interior ministry’s annual report has for many years provided governments with the opportunity to trumpet the success of anti-immigration measures, notably beginning in 2002 with then-interior minister Nicolas Sarkozy. But Bernard Cazeneuve, now prime minister, put an end to the practice in 2015, after he took over as interior minister from Manuel Valls. Cazeneuve’s successor, Bruno Le Roux, has this year followed in the same vein, presenting the latest statistics at a press conference on Monday with journalists specialized in migratory issues.

Since the beginning of the new century, immigrants arriving in France to rejoin family already established in the country has annually concerned between 80,000-90,000 people. It is this group that the French mainstream Right and far-right have principally targeted in their political campaigning, with the conservative Républicains party’s presidential election candidate, François Fillon, promising to “strictly limit” this category of so-called family immigration, even imagining a modification France’s constitution to do so.

The term ‘family immigration’ is most often perceived to be when a head of a family already established in France is joined by other family members. But in 2016, a total of 48,725 residency permits granted in this category concerned the spouses of people of French nationality. Immigration centred on the re-grouping of families, whereby a foreign national established in France is joined by their relatives, and which far-right presidential candidate Marine Le Pen has pledged to put an end to if elected, concerned just 11,500 requests for residency permits in 2016 – an annual figure which has remained stable over the past 15 years.

A number of presidential candidates on both the Left and the Right have said they would impose quotas on immigration for economic reasons (a proposition already mooted in recent years and which former Constitutional Council president Pierre Mazeaud dismissed in 2008 as “unconstitutional”, “unachievable” and “of no interest”), a category which in 2016 concerned just more than 22,000 people.

The one exception to what proved otherwise to be a largely stable table of annual figures was the significant year-on-year rise in 2016 of the number of residency permits given to immigrants who arrived for humanitarian reasons, which rose by 41%.

In this category, 19,845 were given refugee status and which grants residency rights for ten years. Refugee status, as defined by the 1951 United Nations Refugee Convention, applies to those persons who “owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality, and is unable to or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country or return there because there is a fear of persecution”.

Another 5,535 people in the category of immigrants citing humanitarian reasons for establishing residency in France were given a separate and lesser status of protection, which applies to those fleeing war zones, and which allows them right to a renewable one-year residency permit.

Border controls turned back 63,732 migrants in 2016

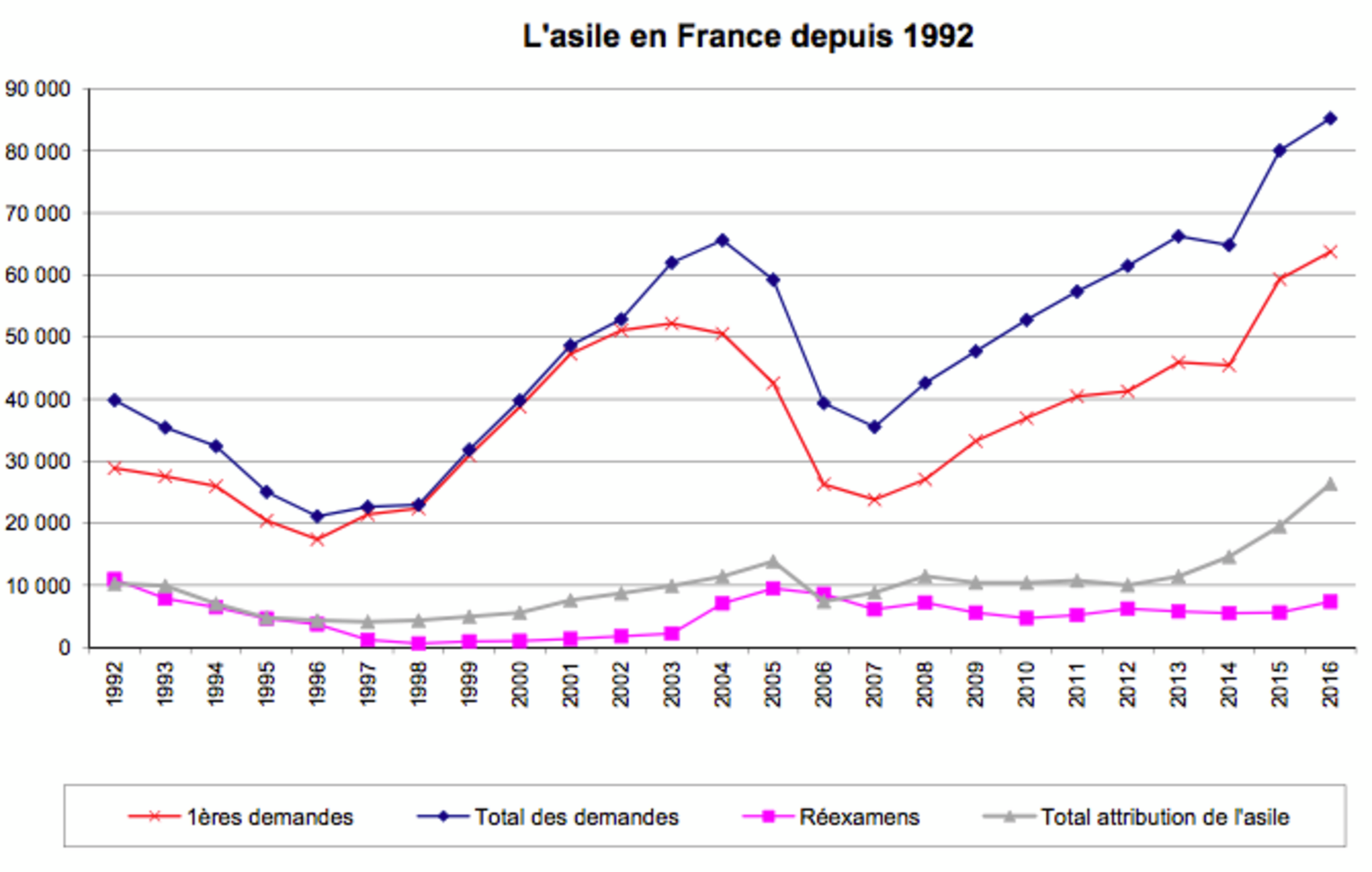

However, the interior ministry reported that the total number those seeking asylum in France, including both first-time applicants and those requesting a re-examination of their asylum requests, totalled 85,244 in 2016, a year-on-year rise of 6.5%. That compared with a rise in the same category in all EU member countries of 12%.

The countries from where first-time asylum seekers came were, in decreasing order, Sudan, Afghanistan, Haiti, Albania, Syria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea, Bangladesh, Algeria and China. The rise in the number of these who were granted asylum last year – 37.6%, compared to 31.4% in 2015 – appeared to be related to the increasing gravity of the conflicts from which the asylum seekers were fleeing.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Despite the French government’s 2015 pledge to take in, over a period of two years, 30,000 migrants from the massive influx across Europe, just 2,696 of those temporarily sheltered in Greece and Italy were admitted into France in 2016. Meanwhile, 3,005 Syrians who had fled to Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey were granted residency. French embassies in the Middle East last year granted another 3,243 visas for humanitarian reasons to Syrian and Iraqi nationals, which principally concerned Christians and Yasidis.

These relatively modest numbers admitted to France were criticized during the ongoing televised debates among candidates in the French Socialist Party’s primary elections to choose its candidate for the presidential elections. Frontrunner Manuel Valls, who last month resigned as prime minister to run as candidate, was last week rounded upon by his rivals for his record in restricting migrant admissions to France. One of them, Vincent Peillon, argued that “humanitarian corridors should have been opened for all those under threat”, to which Valls, echoing the conservative opposition, retorted that “unlimited admission is not possible”.

The number of deportations in 2016 fell to 12,961, a year-on-year decrease of -16.3%, including those in which migrants were sent back to third party EU countries from which they had travelled to France. The interior ministry report observed that this fall in deportations was due to the re-introduction of systematic border controls which in 2016 turned back a total of 63,732 people trying to enter France, representing a rise of 302% compared to the 15,849 people turned back at border crossing points in 2015. Because these concerned people who were refused entry to France before setting foot in the country, they are not included in deportation figures.

Pierre-Antoine Molina, head of the interior ministry’s agency, the DGE, that compiled the data, insisted that the evolution of the figures showed that there had not been a “slackening” of policies towards immigration, as regularly claimed by the right-wing opposition. He criticized the policies previously put in place by former president Nicolas Sarkozy which introduced targets for deportations, arguing that the consequences of these were to incite sending back to their countries “those nationalities which were the easiest to send back”, a reference to Roma migrants from Romania and Bulgaria, and “who came back just as quickly”.

Molina said a priority had now been made to send migrants entering France through third-party countries back to their original homeland, notably Afghanistan, Iraq, and Sudan, which he said was a “message that we want to send” to those contemplating “irregular immigration”.

Finally, the report this week revealed that 29,408 foreign nationals living in France without proper legal status were given residency rights in 2016, a figure similar to the number whose illegal situation was regularised in 2015.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse