Jean-Claude Juncker, the first elected president of the European Commission (EC), pledged to introduce a minimum social wage in every European Union (EU) member state during a speech before the European Parliament on July 15th, shortly before the assembly voted to appoint him to the EC leadership post. Juncker, the candidate of the conservative and centre-right European People’s Party, was attempting to woo support from centre-left Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) – he also pledged to protect European public services from what he called “the whims of the age” - and the tactic worked.

But beyond the electioneering, there is a strong argument that a minimum wage across Europe could contribute to containing the devastating social dumping that is practiced on the continent, while also driving a rise in the lowest salaries in the most vibrant EU economies, beginning with Germany, which would benefit the whole region.

But can the former Luxembourg prime minister really enact that pledge once he takes over the reins from outgoing EC president José Manuel Barroso in November? Would the EC be capable of returning to social policies it has abandoned for so long, and most notably since the financial and economic crisis that began in earnest in 2008?

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The first obvious obstacles for Juncker are contained in the texts of EU treaties, and notably article 153 of the Lisbon Treaty, which state that the EC has no role for deciding the level of remuneration of workers in member states, which is exclusively a matter for national governments.

The EU has only the power to support and complete national legislation on job security, social security and protection for employees (which was in part what was at stake with the modifications to the directive on posted workers, finalized in April).

However, the argument for introducing a minimum wage in every EU member state is gaining ground, and across the political divide, championed by such opposites as the left-leaning, anti-austerity French collective of ‘Appalled Economists’ and the leader writers of the pro-free-market magazine The Economist. Indeed, the German government’s decision last year to introduce a minimum wage as of 2015 appears to have won over a number of doubters.

German socialist Martin Schulz, who was a rival candidate to Juncker for the job of EC president, standing for the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats, had made the introduction of a cross-Europe minimum wage one of the planks of his campaign. László Andor, the current Commissioner for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion had urged continent-wide adoption of a minimum wage two years ago, arguing its use in stemming the massive rise of unemployment across the EU. In every case, the thrust of the idea is to offer a form of safety net for the worst-off who are struggling from the consequences of austerity measures.

Currently, 21 of the EU’s 28 member states have introduced a minimum wage. Germany, in a move driven by the social democrat SPD party, is to progressively introduce a minimum wage over the period 2015-2017. Among the countries still resisting its introduction are Austria, Denmark, Finland, Italy and Sweden, although several have collective bargaining agreements for minimum earnings in different, but not all, economic branches.

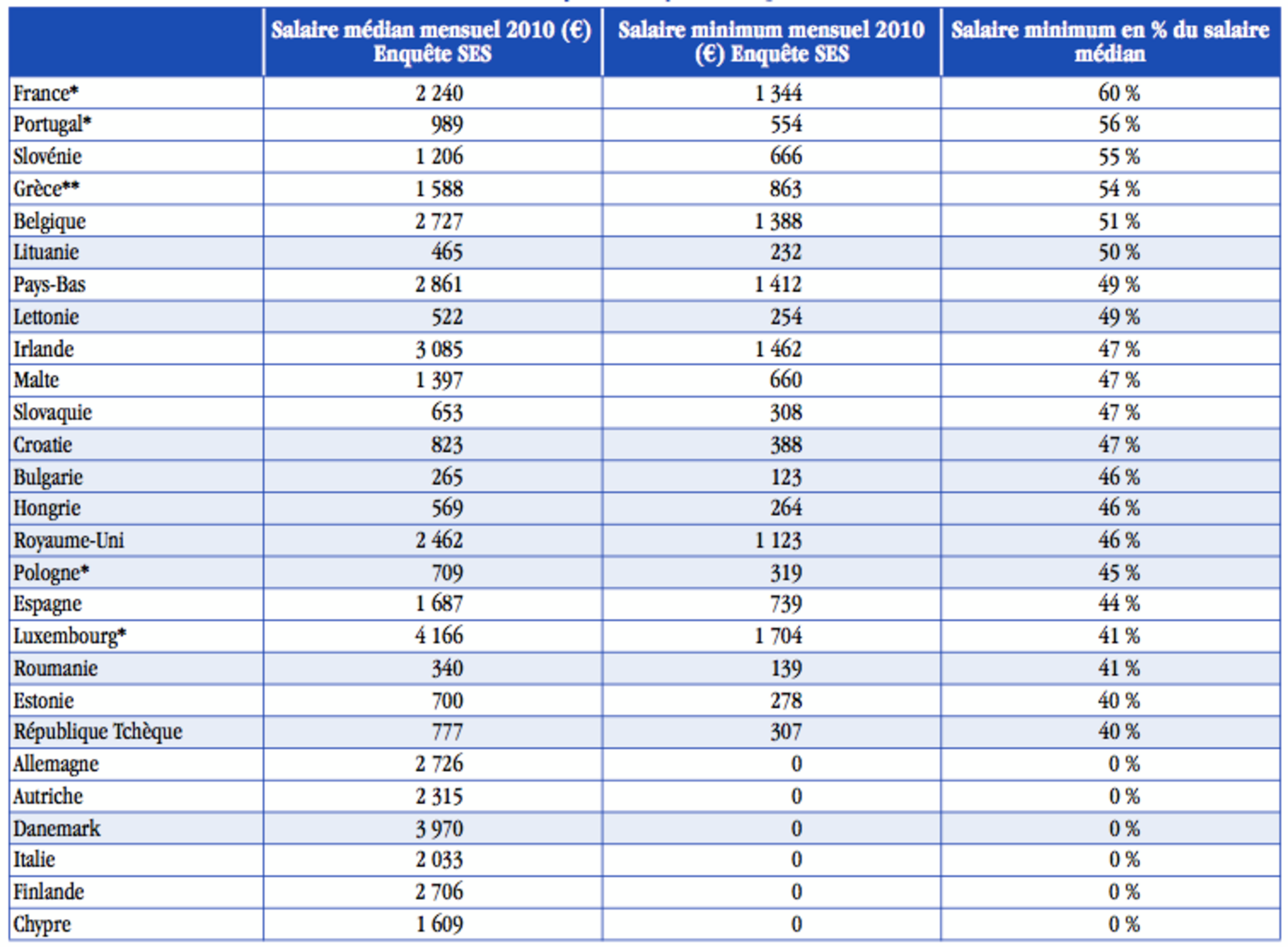

The disparities between one country and another are significant. According to a study published this summer by the French economy and finance ministry’s treasury department, the gap is vast (see the study's table below). It found that Luxembourg offers by far the most generous minimum wage, amounting to 1,704 euros before deductions, compared to 1,344 euros in France and just 123 euros in Romania.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Above: this table from the French treasury department shows monthly median income (in euros) among EU member states in the left-hand column, the monthly minimum wage (where applicable and in euros) in the centre column and, in the right-hand column, the percentage of median income that the minimum wage, in those countries which have one, represents.

To take the widely different living standards of member states into account, a number of economists link the minimum wage to the median income – that is, the income that represents the dividing line that separates all the active population into just two groups of equal numbers, with one group earning less and the other earning more. In this case, the minimum wage in France emerges as the highest, representing 60% of the median salary. At the opposite end of the scale are Romania, Estonia and the Czech Republic which all have minimum wages of less than 40% of the national median income. The proposed minimum wage in Germany is expected to sit at around 55% of median income, at a rate of 8.5 euros per hour.

While Jean-Claude Juncker has not revealed what mechanism he envisages for the application of a Europe-wide minimum wage, several recent studies, including that of the French treasury department, argue the case for a minimum wage ‘standard’. Rather than setting a flat sum, this would allow for a minimum wage calculated as a percentage of the local median income – for example this could be set at 55% - while allowing those states which so desire to fix a higher rate. Annual reviews for an increase in the minimum wage could be harmonised across the EU after agreement on the makeup of a review board, such as trades union representatives and independent economists.

The notion of a Europe-wide minimum wage revives old arguments, and which are often deformed by ideology. These include the fear that jobs are threatened by the introduction of a minimum wage, because companies would show extra caution in hiring staff on higher salaries. The question is far from insignificant on a continent which counts about 26 million unemployed.

Neoclassic economic theorists, who have long dominated policy-making, believe the effects would be negative, and that introducing a minimum wage, and even raising an existing one, would, by pushing up labour costs, reduce competitiveness and force up the price of products. The end result, they argue, is the loss of market share and a downsizing of staff, thereby creating a loss of jobs.

“It is a reasoning that doesn’t stand up, notably because labour is not the only determining factor for the price of a product,” comments Dany Lang, an economics lecturer at Paris-13 University and a member of the left-leaning French economists’ collective, the Economistes Atterés. “A recent study, for example, establishes that when a product costs one euro, the corresponding cost of labour is 15 cents in Greece, 16 in Italy and 17 in Spain. Intermediary costs come into account.” His argument is that even if the rise in labour costs was entirely passed on to the sale price of a product this would not bring about any significant increase. Similarly, it is not by reducing wage costs that a company would necessarily increase its productivity.

Some economists oppose the introduction of a minimum wage for different reasons than the neoclassical theorists. Zsolt Darvas, a Hungarian economist and a member of the Belgian-based economic policymaking think tank Breugel, warns against the “psychological” effects of a pan-European minimum wage which would discourage the motivation of a section of workers and adversely affect business competitiveness. “The minimum wage does have, in certain cases, a negative effect on employment because it creates distortional effects between those who benefit from a minimum wage and those who were until then earning a bit more than the lowest wages and who now see themselves caught up with,” Darvas argues.

The issue is the subject of a more lively debate in the United States where last year President Barack Obama led a campaign to increase the federal minimum wage. Countering the vociferous opposition to raising the minimum wage, notably from the Republican camp, several in-depth studies have concluded that such a rise has practically no effect on employment. While some argue that a worker paid his true value will be more efficient (what neo-Keynesian economists call an ‘efficiency wage’ ) and increase a company’s productivity, others also suggest that employers have different means with which to buffer the cost of a rise in the minimum wage.

“In the traditional discussion of the minimum wage, economists have focused on how these costs affect employment outcomes, but employers have many other channels of adjustment,” reads a report published in February 2013 by the Washington-based think tank, the Center for Economic and Policy Research, entitled ‘Why Does the Minimum Wage Have No Discernible Effect on Employment?’ and authored by one of its senior economists, John Schmitt. "Employers can reduce hours, non-wage benefits, or training. Employers can also shift the composition toward higher skilled workers, cut pay to more highly paid workers, take action to increase worker productivity (from reorganizing production to increasing training), increase prices to consumers, or simply accept a smaller profit margin. Workers may also respond to the higher wage by working harder on the job. But, probably the most important channel of adjustment is through reductions in labor turnover, which yield significant cost savings to employers."

But it can be argued that it is inappropriate to draw lessons for Europe from the example in the US, where the minimum salary is notably low, equivalent to about 38% of the median income. In France, the issue of raising the minimum wage has split the Left, and the debate is often complicated by ideological positions that are removed from the reality on the ground.

Philippe Aghion, an advisor to socialist President François Hollande, and who is also an economics professor at Harvard University and a visiting professor at the Paris School of Economics (l'Ecole d'économie de Paris), is in favour of the principle of a minimum wage across Europe but sees a problem with the level of the French minimum wage, the Smic. “As of a certain level, when the Smic is given a boost whilst not [also] touching other salaries, we run the risk of reducing social mobility by discouraging the employment of young or unqualified workers, by reducing the range of remunerations and by blocking promotion,” he said in an interview in May with French financial daily Les Echos.

In a book published in April, co-authored with French economists Elie Cohen and Gilbert Cette and entitled Changer de modèle (Changing the model), Aghion argues the case for “freezing the Smic in the short-term”, broadly echoing the view of The Economist which, in a December 2013 editorial, concluded that “moderate minimum wages do more good than harm”. The venerable British weekly went on to offer France as the perfect counter-example of this. “High minimum wages, however, particularly in rigid labour markets, do appear to hit employment,” it argued. “France has the rich world’s highest wage floor, at more than 60% of the median for adults and a far bigger fraction of the typical wage for the young. This helps explain why France also has shockingly high rates of youth unemployment: 26% for 15- to 24-year-olds. “

There is every probability that Jean-Claude Juncker will adopt an almost identical position: in favour of a European-wide minimum wage, but at low, even very low, levels of pay. Fixing what the EC deems to be appropriate will be the crux of the issue. “To angle for a fall in the level of the minimum wage is, over a period of years, [tantamount] to reduce the whole range of remunerations,” says Dany Lang.

For Paul De Grauwe, a professor in European Political Economy at the London School of Economics, the current economic crisis, which stems from the bursting of the US property market bubble, is above all a crisis of demand - and not one of supply, as the majority of European leaders continue to believe. From De Grauwe’s analysis flows the Keynesian-like idea of raising the level of some of the lowest wages.

Increasing wages is one of the possible paths for a revival of European economies, argues Engelbert Stockhammer, a professor at London’s Kingston University and a specialist in macroeconomics, financial systems and political economy. He argues that it is for countries with a trade surplus, those who export more than they import, such as Germany, to enact the largest increases in wages. “The EU must establish a base wage, that takes the shape of a differentiated minimum wage system, which would allow for an end to the competitive devaluations of some economies which played on a fall in wages,” he says, in a reference to countries like Greece and Spain.

László Andor, European Commissioner for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion was close to that analysis when in April 2012 he published a paper of propositions to tackle Europe’s chronic unemployment. "Targeted [wage] increases, which help sustain aggregate demand, might be feasible where wages have lagged significantly behind productivity developments," wrote Andor, in a thinly-veiled criticism of German labour policies. The paper also argued that "setting minimum wages at appropriate levels can help prevent growing in-work poverty and is an important factor in ensuring decent job quality." But Andor, a Hungarian economist and socialist, never enjoyed much clout within the EC which, at the height of the economic crisis, was dominated by champions of austerity - and notably economic and monetary affairs commissioner Olli Rehn.

Two years after Andor’s suggestions, those now also arguing for a rise in wages as a weapon against the crisis gripping Europe received a boost from an unexpected quarter when Deutsche Bundesbank president Jens Weidmann, in an interview with German daily Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung published on July 30th, he said he was in favour of a rise in wages in Germany, and suggested that a hike of 3% would be desirable.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse