The question was openly raised by the newly-elected Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras during his policy speech before parliament on February 8th, and it is one that could well poison even further the already strained relations between Athens and Berlin.

Greece is now seeking reparations for the destruction caused by the German occupation of Greece during World War II, along with the refund of a loan to Germany that the Nazis forced upon Greece and which together total, according to one, possibly modest, estimation more than 160 billion euros, excluding interest payments.

The broad demands appeared on the agenda of talks held in Berlin on February 11th between Greek foreign minister Nikos Kotzias and his German counterpart Frank-Walter Steinmeier, although that first salvo from Athens met with a predictable and firm negative response.

The issue was already given serious consideration by the conservative Greek government of Antonis Samaras, which set up a commission to study the amounts Germany owed Greece although no approach was made to Berlin. But now the new radical-left Syriza government has gone on the offensive, and the spectre of raking over Germany’s wartime past is causing unease both in Berlin and in Brussels. But what are the legal and historic grounds for the Greek claim?

To find out, Mediapart sought out the differing opinions of specialists on the subject, and reviews the evidence point by point.

THE 1953 LONDON 'AGREEMENT ON GERMAN EXTERNAL DEBTS'

In an interview in November last year with the US news and political analysis website Truthout, Albrecht Ritschl, a German professor of economic history with the London School of Economics (LSE) said post-war Germany’s default and the forgiveness of its debt amounted to a sum that was “probably unrivalled” in the history of the 20th century. He notably cites the 1953 London Agreement of German External Debt (also known as ‘the London Debt Agreement) as having made possible the so-called economic miracle witnessed on post-war West Germany over several decades.

Those who took part in the conference that settled the London agreement were keen to avoid the mistakes of the harsh economic punishment imposed upon Germany in the June 1919 Treaty of Versailles that followed World War I, the consequences of which British economist John Maynard Keynes had warned of in his book The Economic Consequences of the Peace published that same summer.

Timothy W. Guinnane, a professor of economic history at Yale University, argues that the 1953 London agreement “reflects a subtle and responsible understanding of the problems associated with the reparations and debt crises of the 1920s and 1930s.” The conference negotiations ended with the agreement to slash external German debt by 50%, and also to extend the date for repayment of the remaining 50% to when West and East Germany would be reunited.

The generosity of the deal is above all explained by US concerns that West Germany, its new ally in the Cold War, was not weakened further, and Washington offered west European nations access to the Marshall Plan in exchange for aligning themselves to its position on the German debt.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

But 37 years later, after the fall of the Berlin Wall and in the preparations for the formal reunification of Germany, the then German Chancellor Helmut Kohl finally got rid of the issue, and to Germany’s considerable advantage. The September 1990 Treaty on the Final Settlement With Respect to Germany (also known as the Two Plus Four Agreement) was an agreement settled in Moscow and signed between representatives from West and East Germany and the four powers which had occupied Germany since the end of the World war II – the US, Britain, France and the USSR. The deal paved the establishment of the new sovereign Germany, and in the process wrote off most of the debt Germany was due to repay under the terms of the 1953 London Debt Agreement. “The only demand made was that a small remaining sum be paid, but we're talking about minimal sums here,” underlined the LSE’s Albrecht Ritschl in an interview with German weekly Der Spiegel in 2011. “With the exception of compensation paid out to forced labourers, Germany did not pay any reparations after 1990 - and neither did it pay off the loans and occupation costs it pressed out of the countries it had occupied during World War II. Not to the Greeks, either.”

Kohl’s move to escape repayment of the debt met with a consensus of agreement among West European nations. The exact total of Germany’s initial post-war debt to other countries – and which was halved under the 1953 London agreement – is estimated by Ritschl to total about 2 trillion euros.

What is the lesson that can be drawn from all of this regarding Greece’s situation today? “The only conclusions that can be made from this comparison are very wide, such are the contexts so different,” said Éric Monnet, a teacher at the Paris School of Economics (PSE), specialised in Economic history and monetary macroeconomics. “It reminds us that the political Europe was built on the rejection of Nazism and that Europe would not exist today if it had not been decided, at one point, to not demand reparations for the material and financial damage caused by certain countries including Germany.”

Following World War II, the German debt was far greater than that of Greece today. But, stressed Monnet, Germany, divided into four occupied zones, did not have political autonomy, and was therefore territorially and legally different to the country that contracted the debts in the first place.

Official Greek estimation of German debt still secret

“The London agreement of 1953 can in no case be used in the debate to say that Germany still owes Greece money because it did not concern war reparations but a payment of the debt from before and after the war,” added Monnet. “On the other hand, this treaty shows very well how the allies went about reducing and staggering the German debts after the war in order to avoid the problems of the inter-war period from reoccurring. Having had a balance of trade surplus during the 1950s and 1960s, and strong growth, Germany was able to rapidly refund what the 1953 treaty had left it to pay off.”

WAR REPARATIONS

Within Greece, the subject of war reparations is nothing new. What is new is that a government officially takes up the matter.

Until 1990, there was no legal possibility for Greece to reclaim anything from the German authorities given that the 1953 London agreement set out that neither the remaining German debt nor the issue of reparations would be settled before the reunification of the country.

During the post-war decades, the Greek government buried the question of seeking indemnities from Germany. “At the time, priority was given to good Greek-German relations in order to help the economic growth,” said Dimitris Apostolopoulos, a researcher with the Academy of Athens specialised in postwar Greek-German relations and modern Greek history. “During a trip to Bonn in 1958, Greek Prime Minister Consantine Karamanlis even signed a loan from the German government of 200 million deutschmarks. It was a loan with a considerable interest rate. That had nothing to do with indemnities. It was said that Karamanlis indicated to the Germans that the Greek state would abandon any demand for reparations. But there was no confirmation from any written source.”

Apostolopoulos believes that Greece, like Britain, France and the US, did receive some compensation from Germany in the immediate post-war period. “Concerning Greece, estimations are of the equivalent of 25 million dollars,” he said. “That represents hardly 0.12% of what Greece demanded at the 1946 [Paris Peace Conference]. In other words, it is a symbolic amount and, as of 1953, all the [financial] transfers are halted.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In 1960, Germany offered compensation to some recognised Greek victims of Nazism, based on the model of a 1952 compensation agreement between Germany and Israel. A sum of 115 million deutschmarks was paid by Bonn, mostly to members of Greece’s Jewish community. During the occupation by Germany, 95% of the Jewish population in Greece was exterminated. The compensation was similarly given to nine other states, although none was handed to East European countries until after 1990. However, the one-off payment did not relate to war reparations, and no payment for economic and material damage caused during the war was ever made to the Greek state.

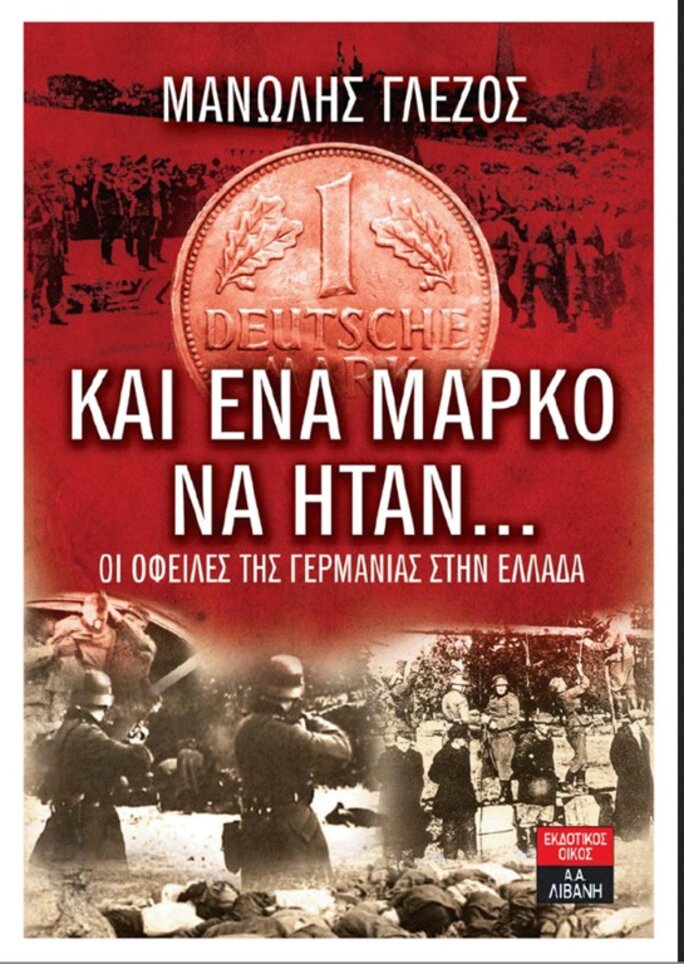

After 1960, successive Greek governments shelved the question for diplomatic reasons, but in the late 1990s a group made up mostly of former wartime resistance fighters led by leftist politician, writer and wartime resistance veteran Manolis Glezos, created a ‘National council for the claiming of German debts to Greece’. Glezos, a European Member of Parliament (MEP) for Tsipras’ Syriza party, drew up four categories of German debts: looted archaeological treasures, the loan to Germany imposed upon Greece in 1941 (equivalent today to 54 billion euros before interest), reparations for material damage caused during the war (the estimated cost of which at the 1946 Paris Peace Conference would be the equivalent today of 108 billion euros before interest), and compensation for victims of the German military (who were in part compensated in 1960).

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Today, the government of Alexis Tsipras is focusing on reparations and the forced loan, which together – and before interest – total 162 billion euros based on the calculations of Manolis Glezos. In comparison, Germany is today estimated to have contributed 72 billion euros in plugging the Greek national debt.

In relation to the size of its population and territory, Greece is one of the European countries that suffered the worst from World War II, when it was occupied first by the Italians, from 1940 to 1941, and then by the Germans, from 1941 to 1944. Apart from the roads, railway lines and other vital infrastructures that were destroyed, more than 80 populated sites, mostly villages but also towns, were flattened and inhabitants murdered. The occupation of Greece was also a period of famine, when most of the country’s agricultural produce was earmarked for German troops in Africa. According to the research led by Manolis Glezos, who has published a book on the question of reparations and debt repayment entitled Even if it was about one deutschmark, 13.5% of the Greek population perished during the war, when 600,000 people died of hunger, 105,000 others died after deportation to death camps, and another 56,000 were executed.

Glezos, who at 92 is the doyen of MEPs, is well known in Greece and beyond for his resistance past, notably when he and a companion, Apostolos Santas, climbed onto the Acropolis in Athens in May 1941 and removed the Swastika that the German occupiers had placed on it one month earlier. Glezos believes that the reason Greece has never received reparations is because of the lack of courage of successive Greek governments. Over the past three years, since Syriza has taken up the case for reparations and debt repayment, the campaign has been met with a certain degree of support among the Greek population for whom World War II and the civil war that followed it remain very present and highly sensitive in the collective memory. Before Syriza came to power in January, the issue was raised so widely, and notably in parliament, that the preceding conservative prime minister Antonis Samaras, of the New Democracy party, finally recognised that it was indeed a legitimate subject for discussion.

In 2013, Samaras set up a commission within the state budget administration, and under the management of the finance minister, to evaluate the amounts of money that Germany owed Greece. But its conclusions, which were finalized at the beginning of the year, have never been made public and no action, let alone official contact on the question with Germany, was ever taken by Samaras.

'We are partners with equal rights'

Things have changed since the arrival in power of Syriza, but while the Tsipras government has placed the issue on the table, it has also remained secretive about the amounts it intends to ask of Germany. Contacted by Mediapart, the Greek foreign ministry said it had “no comment” to add to foreign minister Nikos Kotzias’s statements in Berlin in February, and that for the moment the starting point is the confidential report prepared by the Samaras-appointed commission.

According to Greek press reports, which were followed by no official confirmation, the amount that the commission estimates is due to Greece is 311 billion euros. Indeed, when the commission’s report was handed to the Samaras government on January 19th, Evanguelos Venizelos, then deputy-prime minister, described the total sums involved as “colossal”, adding: “For the loan they are small, for the indemnities they are very big.”

The Greek government's first aim is that Germany recognizes its debts to the Greek nation. For Dimitris Apostolopoulos, specialist in the subject with the Academy of Athens, to evaluate the economic and material losses suffered by Greece at the hands of Germany – and to calculate the corresponding interest owed on top – remains extremely complicated. Furthermore, Greece is not the only country to have never received reparations from Germany, and if Berlin were to accept the principle of its debt towards Greece it could well open up a floodgate of similar demands from other nations it once occupied.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

“On the other hand, the [forced] occupation loan [to Germany] is proven by sources,” said Apostolopoulos. “It is also a unique case during the Second World War, no other country suffered a forced loan in this manner. I myself have seen the documents in the Berlin archives. The Reich imposed upon Greece a loan of 376 million Reich marks. The first repayments were made and then nothing more. It is easy to calculate what has never been refunded. It is an objective fact, the German government cannot deny written documents.”

Apostolopoulos argues that Athens should separate its claims into two, the loan on one side and reparations on the other, if it hopes to gain any ground with Berlin. He is also critical of the fact that no precise sum has ever been officially presented in public. “One doesn’t know what’s being talked about and the different types of reparations are mixed together,” he added.

COULD RECOVERY OF GERMANY’S DEBT PROVE A SUCCESSFUL STRATEGY FOR GREECE?

In the corridors of the EU and its institutions, there are many who are ill at ease with the Greek demands, which they argue are counter-productive. While negotiations over Greece’s sovereign debt are set to last for several months ahead, there is a fear that such a sensitive issue will only serve to set in stone Germany’s already largely uncompromising stance over its insistence that Athens sticks to the harsh austerity measures imposed over its bailout. "By claiming World War II reparations,Tsipras undermines the fundamentals of European integration,” commented former Belgian prime minister Guy Verhofstadt, who now sits in the European Parliament as a leader of the centre-right Alliance of Liberals and Democrats party. “He seems to have forgotten that former enemies made a vital choice to cooperate and build on a common future after the Second World War. By doing that, they repaired the mistake that was made in the Versailles Treaty after the First World War."

"Tsipras’s claims are very unhelpful and will only make it more difficult to find a compromise,” Verhofstadt added. “Instead of breathing new life into the phantoms of the past, he should put all his efforts into building a new future for Greece. Revenge should not make part of this common European future."

French centre-right MEP Sylvie Goulard, whose UDI-Modem alliance in France is part of the same European group as Verhofstadt’s, and who took part at the start of her legalistic career in the French foreign affairs ministry in the 1990 ‘Two plus Four’ Moscow treaty negotiations, says the Greeks have chosen the wrong path over their reparations claims. “It would be perilous to open up the Pandora’s box from the past,” stated the former advisor to ex-European Commission president Romano Prodi. Goulard, who in 2003 was awarded the German Federal Cross of Merit, argues that the 1947 Marshall Plan and the 1953 London Debt Agreement were designed to “mark a cross on the past, construct a common future” after the destruction left by World War II. “Idealistic in appearance, this solution has proved to be infinitely more judicious than the cycles before the wars, reprisals and reparations,” she added.

Are the Greeks in the process of dismantling one of the pillars of the project that became the European Union, stuck in a viewpoint seen as too nationalistic for some in Brussels? For Manolis Glezos, the amount of reparations that Germany owes Greece is not in itself the most important question. What is, he argues, is the gesture from a country which has, since the start of the sovereign debt crisis, demanded incessant and extreme efforts on the part of the Greek people large swathes of whom have been plunged into a humanitarian crisis. “Even if it was about a debt of one deutschmark, Germany has the legal, historical, and above all ethical, requirement to settle its debt with Greece,” Glezos writes in his book, underlining that the Greek resistance played its own important part in overthrowing the Nazi regime.

At their joint press conference during his visit to Berlin on February 11th, Greek foreign minister Nikos Kotzias, whose wife is German, told his German counterpart: “Reading the German press, I feel that I should make it clear that what we are asking for, entreating for – choose whatever word you want – is understanding. We cannot continue the policy that was imposed upon us, because our society is collapsing, our productive base has almost vanished, and economic growth is not possible. And without economic growth, the debts cannot be repaid. Germany is well aware of this, having experienced the agreements of 1952-1953. [...] Naturally, we will talk about the issue of reparations. I am, if you will, a postman for the Hellenic parliament.” But German foreign minister Franck-Walter Steinmeier’s reply was crisp. “We remain firm in our view that all of the questions regarding reparations and the forced occupation loan have been settled definitively from a legal standpoint,” he retorted.

The Greek reparations claims and the refund of the loan imposed on the country during the occupation could possibly prove a means to a different end, such as placing pressure for German investment in major projects to kickstart the Greek economy. What is clear, however, is that the Tsipras government wants to see Germany display a degree of humility instead of its perceived high-handed, table-thumping imposition of further draconian austerity upon an exhausted nation. “The main thing for me, as foreign minister, is that my colleagues and our partners should see us as partners with equal rights,” added Kotzias at the February 11th conference. “Over the past five years, we have had only failures. Being poor doesn’t mean not having rights. The poor, too, have the right to vote and share in decisions.”

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse