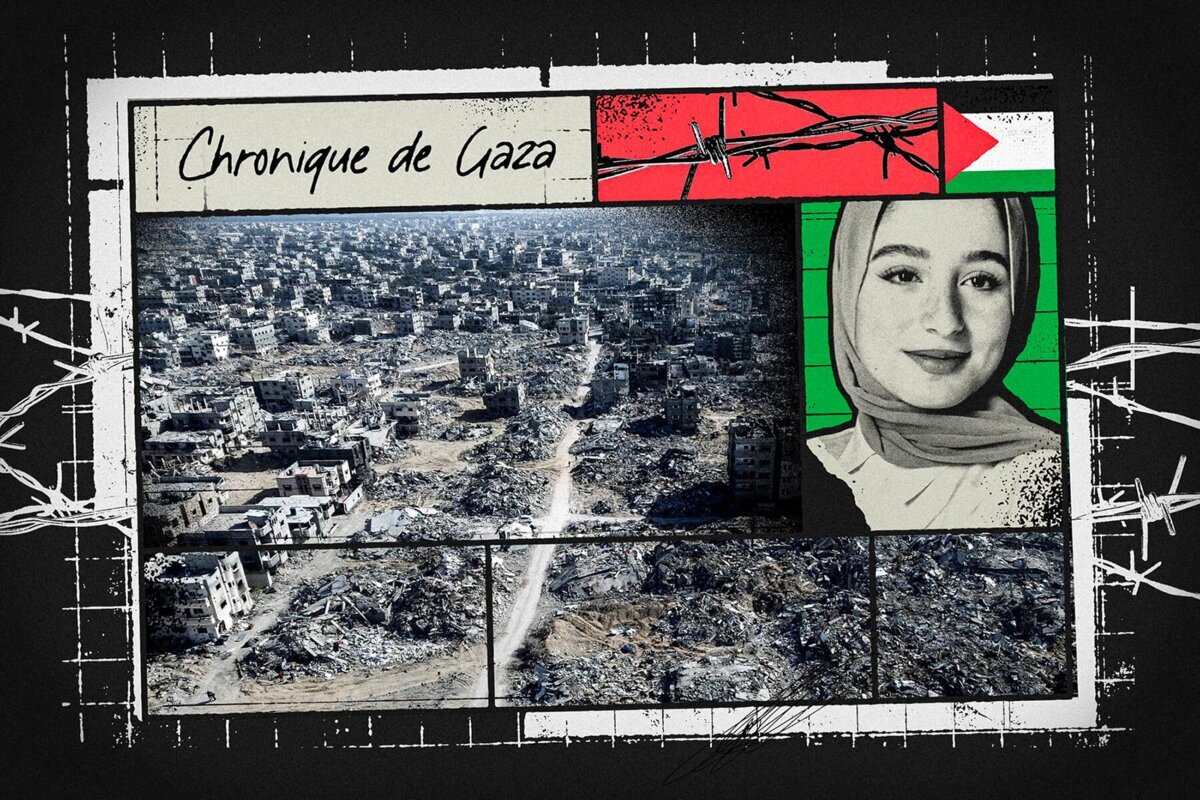

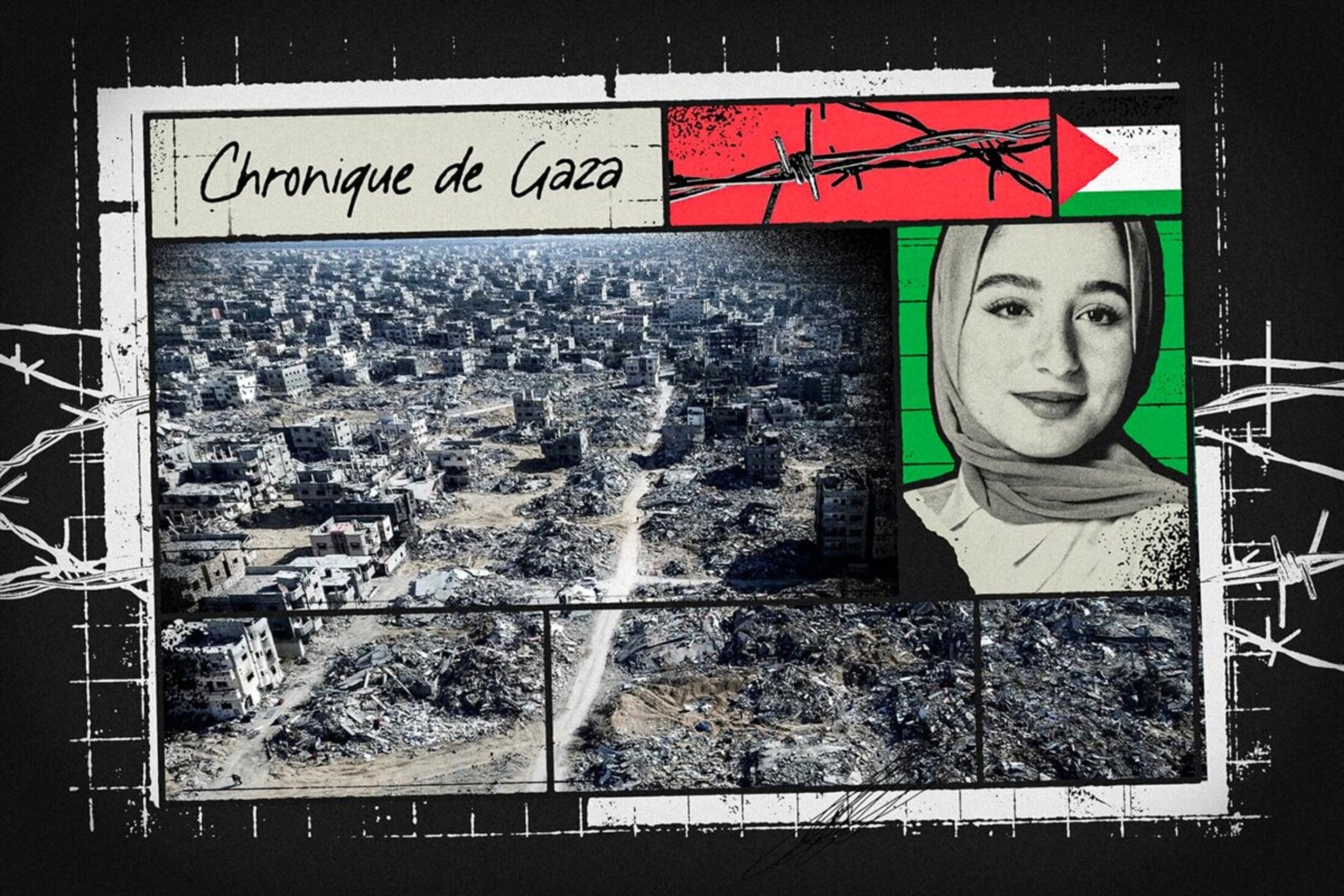

Nour Elassy, whose higher education studies were in English and French literature, was born and raised in the Gaza Strip, in the north-east neighbourhood of Tuffah. After Israel’s invasion of Gaza, following the Hamas attacks of October 7th 2023 that left more than 1,200 Israelis dead, she and her family were displaced and lived for almost 15 months in Deir al-Balah, a town in the centre of Gaza.

She returned to the north in February this year, but in April she and her family were again forced to move.

She says writing is essential for her. She began composing poetry shortly after the October 2023 Hamas attacks against Israel, and has published them online, notably on Instagram.

Below, Elassy recounts how she left Gaza earlier this month, with the help of the French authorities, after being offered a place to study at the prestigious Paris School of Advanced Studies in the Social Sciences (EHESS), leaving behind her mother and sister. Her account is published below in its original English version (and can be found here in a French translation).

-------------------------

Leaving Gaza to avenge it

I am writing this from Paris, with its July rain spraying softly over my cheeks, as if it is apologising to me for the amount of pain I am feeling, like it can sense how fragile I am after leaving my entire world to pursue my dream.

The days before the evacuation were the bloodiest we had ever seen. The sky burned louder. The earth cracked deeper. The number of airstrikes, evacuation orders, and massacres climbed beyond anything countable.

The French Consulate said it was time, not because it was safe, but because Israel finally allowed them to do so. So we moved to Deir al-Balah to wait for departure. I didn’t sleep. I watched my family breathe, memorizing their voices like they might vanish. Because they would.

I walked out of Gaza with nothing but the clothes I am wearing, my ID, and the unbearable ache of knowing that my mother and little sister, my entire world, would stay behind in a war designed to erase us.

The talks of a close ceasefire and high hopes of ending this war, made me a little calmer, but today that progress is frozen. It's a recurring spectacle, and we fall for it every time. Not because we are idiots, but because we are desperate.

The French consulate told us a few days before: get ready, if you still want to leave. To pursue my studies, I have been admitted to study political science at the EHESS school in Paris.

But how do you pack for exile? How do you fold your memories into a backpack you’re not allowed to carry?

The night before I left, I tried to memorize my sister’s eyelashes. I slept between her and my mother, all hugging like it was the last, a big part of me and them also wanted so badly to deny it.

She was quiet. Too quiet. That terrifying kind of quiet that comes from children when they know more than you want them to. She didn’t say “don’t go”. She just looked, and hugged me even tighter. And that look will follow me longer than this war. And my mother, oh I have no strength to write this, I cant forget her look and how she cried her heart out while pushing me out of the room to leave.

I walked away like a thief, not stealing, but leaving everything I ever loved behind.

We waited in Deir al-Balah, where we were forced to evacuate anyway because they said it is safer in the south. There, at the meeting point that the consulate agreed on huddled with others chosen for this mercy evacuation. Thirty of us. Maybe more.

Each of us carrying stories we’ll never finish writing. We boarded the buses like ghosts wearing bodies, each with tearful eyes, swollen from not having slept, each sadder and more confused than the last.

I sat by the window and forced myself to watch, to witness the death of what was my home. Khan Younes. Rafah. Or what was Khan Younes. Rafah. Everything was gone. Flattened into an architecture of silence. Concrete bones. Burned laundry. Even the birds flew lower, as if in mourning.

I have no words to describe the scale of the destruction — and my ignorance of it — on the road leading to the Kerem Shalom-Abu Salem border. I couldn't believe my eyes; it looked like something out of a movie about the end of the world, but it wasn't.

Then we drove past the trucks, the aid trucks. Lined up like props at a crime scene. There were dozens of them. Filled with food. Flour. Water. Parked a few meters from the corpse of Gaza, they were never allowed inside. The bread rotted while the children in the tents boiled grass for dinner.

What else do you call this, if not a war crime? This isn't a siege. This is starvation as foreign policy.

This is bureaucracy as genocide. This is murder by paperwork, signed in Washington, implemented in Tel Aviv, and witnessed by Europe.

We reached the checkpoint. After checking our IDs, the Israeli soldiers waited, rifles in hand, as if we were the threat, not the victims.

They told us, "Bring nothing." No laptops. No books. Not even headphones.

I wasn't even allowed to take the poetry notebook I'd filled during the war, the one my sister had given me for my birthday. Words, apparently, are too dangerous for the occupier.

They searched our bodies as if we were carrying bombs; not grief. They touched our backs, checked our socks, scanned our eyes. One soldier, if that's how you can describe a criminal, looked at a student travelling with us and began questioning him about where he lives and who he knows.

The consulate team checked our names again and were so kind and warm. They gave us food and informed us that their team from the French Embassy would be waiting for us upon our arrival in Jordan.

On the bus to Jordan, no one spoke. But grief has its own language. Our silence was a hymn. A funeral song for the families we left behind. For the children we may never see again. For the truth we were forbidden to bear.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Two seats behind me, a girl whispered. She didn't ask my name. I never asked hers, but she said: "My father stayed behind. He said he'd rather die in his house than in a tent. My little brother is 5. I told him I'd bring chocolate back from France. He smiled. He doesn't know this might be a forever goodbye."

She pulled her sleeves over her hands, looked at the ground, and whispered again: "I feel like I left my soul under the rubble. And now I'm afraid someone will walk on it." But a sentence she said still haunts me today: "I am convinced that I will return to my mother and explain my trip to her, and she will say to me: 'Hello, my daughter, you are late!'"

No crying. No sobbing. Just silence, and a silence so heavy it pressed on our lungs. Like me, that girl is somewhere in France now. Eating bread. She's studying French, law, or some other science. But a part of her, a part of all of us, is still in Gaza, screaming behind a collapsed wall that no one can break through.

We passed into the Palestinian occupied territories. Four hours passing through a land I'd never seen. Because we're from Gaza. We've never seen our own land. The rest of Palestine has always been forbidden to us.

And yet, there it was: mountains. Vineyards. Hills covered with olive trees. The Dead Sea and, finally, the beach resorts. The five-star hotels, the Europeans tanning in bikinis while, 30 kilometers away, children are buried, several at a time, in a tent.

This is the cruel theatre of occupation: genocide in the Mediterranean, cocktails in the Dead Sea.

We were set up in a hotel in Amman, at the InterContinental Jordan, a beautiful hotel, all of whose expenses were covered by France. It had everything you could need, but never what you wanted.

We spent two nights there, from Wednesday, July 9th, to Friday, July 11th, at dawn. It was two whole days of silence and loneliness in a very luxurious hotel room. We were driven from the hotel to the airport, lots of waiting and checking, and finally put on a flight to Paris.

The trip was so overwhelming. It was my first time flying. I felt very sick while marvelling at the immensity of the world. And how a tiny piece of land made the entire world wake up and realise how wrong they were.

We landed at Paris Charles-de-Gaulle airport. We were checked again and stamped with a student visa. My great friends were waiting for me with the most beautiful flowers and a very warm hug. Here I am in Paris now. Safe. I sleep in a warm, comfortable bed. And every night, I stare at the ceiling and ask myself: Have I betrayed them? Have I abandoned my mother, my sister, my people?

Guilt burns in my stomach and prevents me from keeping anything, be it food or tears. Was leaving an act of courage or desertion? But I know one thing: I didn't leave Gaza to forget it. I left to avenge it, with language, with politics, with a memory sharper than bullets.

I left to learn the language of the courts that never saved us. To use their own tools to carve our name back into history.

You, in your embassies, your newsrooms, and your TV studios, you will hear about me. I won't be your success story, I will be your mirror. And you will not like what you see.

I left Gaza with nothing. No bag. No books. No goodbye gift. Only rage.

-------------------------

Ibrahim Badra has a bachelor’s degree in both English literature and translation from the Islamic University of Gaza. He was due to be awarded with the diploma on October 7th 2023, the day of the Hamas attacks against Israel when his world was turned upside down.

His family were originally from Jaffa. Following the 1948 creation of the state of Israel, and the ensuing displacement and dispossession of Palestinians, they set up home in Sabra, a neighbourhood just west of Gaza City. Badra had lived through seven Israeli-Palestinian conflicts before the war that began in October 2023, following the Hamas attacks that month which left more than 1,200 Israelis – mostly civilians – dead.

His interests focus on literature, politics, education and translation. His work activities over the past year and a half have consisted mainly of defending human rights in Gaza, documenting the daily lives of the local population, and making their voices heard.

Badra's chronicle below, written in late June, is published here in its original English, and in a French translation here.

-------------------------

Another day of not dying in Gaza

Our day began with the sound of tank shells, the sound of advancing military vehicles, and the buzzing of flies inside the tent due to the heat. But it became normal. The sound of shells or vehicles didn't matter. I don't know, have we stopped feeling afraid? Or have we become indifferent to our lives, whose chances of survival diminish with every second, every minute, and every day?

My mother woke us up at six in the morning. We prayed the dawn prayer and got ready to go look for the nearest street where a water truck was parked. Sometimes, it stopped on the same street where we lived, and this was like our lucky day. We didn't feel tired or exhausted, just carrying buckets a short distance. Unlike many days, when the parking spot was far away, on other streets, and we might have to walk kilometers just to secure two buckets of water.

During our displacement in Deir al-Balah, there was a seawater desalination plant. It pumped water to the displaced people, and it was only one long but stable street away from us. Despite the exhaustion of waiting and carrying buckets, the good thing was that we knew where to get water. We were going every morning at 5am to book a place in the queue for water. The wait would take an hour or two. If we went later, like 8am, we could wait four to five hours just to fill two buckets.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

But Salman, the vendor, told me that Israel had bombed Iran and that nuclear scientists had been killed in the bombing. Another person said happily, "Oh, finally they'll forget about us for a while and find someone else to distract them, so we can take a breather from the killing and the river of blood."

As we walked, we saw elderly people, children, women, and young people. Each one of them carried a pot, a bowl, or an empty can, looking for food or a "tekiya". The latter is a place that provides food to displaced people free of charge, but it doesn't have a fixed location or time. So, you'd see anyone carrying a pot and ask, "Do you know where the tekiya is?" This is the most common question we hear in Gaza daily.

This is life in war. We divide roles within the family: some of us are responsible for securing food and others for securing water.

After filling the water, at 10am, I went to buy falafel, the daily breakfast for all residents of the Strip. Sometimes, it's the only meal of the day. A single falafel piece costs 1 shekel ($0.27), while before the war, ten pieces cost 1 shekel. To buy ten pieces, we now need ten times the original price, which means ten shekels!

The internet had been cut off for three days in the entire Gaza Strip, except for the town of Nuseirat. Customers started asking for news. I asked Salman, the falafel vendor, if there was any news. He told me that there had been a bombing at dawn on an UNRWA school for displaced people and that more than 15 people had been martyred. "What was their fault? They were sleeping?"

I asked him if there was any news about our block and whether it had received an evacuation order, because all the residential blocks behind us had received evacuation orders: 109, 108, 106, 47, except for our block, 110. All indications show that we will soon be displaced for the twenty-fourth time. It's just a matter of time. A week? Two weeks? We've become experts at knowing when we'll be displaced.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The beauty of the tent is that when you're about to die, the Civil Defense won't have to struggle to retrieve your body. They might even pull it out in pieces or burned due to the flammable quality of the tents sent by the Arabs. Death has become easier for us than living inside a piece of cloth that doesn't protect us from the summer heat or the winter cold.

After securing water, we went to the market to look for any food at an affordable price. We went to the "Al Nus" market near Al-Aqsa University in Khan Yunis. I was with my mother and my brother, Zakaria. We started asking about flour, but it was 85 shekels ($23) a kilo – and it wasn't even available, just the price was showing. A kilo of rice was 55 shekels ($14.85). We asked about vegetables: a kilo of tomatoes cost 60 shekels ($16.20), potatoes 70 ($18.90), and onions were ridiculously expensive, 360 shekels ($97.20) per kilo! Before the war, 12 kilos of onions cost just five to ten shekels ($1.35–$2.70)!

I didn't know: would we survive? Would we stay alive? If we weren't killed by the bombing, would we starve to death?

After that, we decided to part ways. My mother and brother went to look for flour, available only at a price but doesn't even exist. I was walking around the market and found a fancy restaurant selling lamb soup. A cup cost 5 shekels ($1.35), and there was a piece of lamb fat in it. I drank it. At least it tasted good, because there was no meat and we’ve almost forgotten those things called chicken or meat. But it was very good soup. I bought a litre of it for 15 shekels ($4.05) to make lentil soup.

Lentils, the only friend we had left. It didn't abandon us even in the most dire moments of famine. It didn’t let us down like the governments of the world did, and it didn’t settle for fake statements of condemnation. Lentils stood with us, and we made everything from it: bread, soup, coffee, biscuits...From Khan Yunis, the Al-Amal neighbourhood, Block 110, which will soon be evacuated... I am grateful for lentils in this endless war.

I returned to the tent and found my mother and brother had bought new lentils. Although we stock up every week, we buy more each time. It now costs 20 shekels ($5.40) per kilo, while before the war, it was only 3 shekels ($0.81). We rested from the walk, and then I went to light a fire for my mother. She made lentil soup from the meat soup I had bought, and it tasted amazing. I don't know why we were so happy. But really, we haven't tasted anything like meat in more than a year.

My brother Ahmed came and said that the American aid today was a disaster. More than 30 martyrs and more than 1,000 injuries. He asked my mother if he could go there to get some food: pasta, flour, or cheese – we'd forgotten what it looked like over seven months ago. Even in the market, when it was available, the price of cheese was insane.

My mother refused categorically. She told him, "even If we're going to die of hunger, I won't let you go. I've been patient for over two years, and we've escaped death more than once. And you want me to let you go to your death on your own two feet for a little food?"

The only thing I keep asking myself is: when will the world and the governments stand with us, like the lentils do, and stop this war?

-------------------------

Editing by Graham Tearse