The prominent Islamic intellectual, scholar and preacher Tariq Ramadan, a professor of contemporary Islamic studies at the University of Oxford, was earlier this month placed under investigation in France following separate complaints lodged against him last October by two women who alleged he had raped them, and was placed in preventive detention.

The move came after a three-month preliminary investigation, which considered the evidence against him was strong enough to justify the opening of a judicial investigation, headed by an examining magistrate. The events are alleged to have taken place in a hotel room in the southern French city of Lyon in 2009, and at another hotel in Paris in 2012, accusations which he has denied.

Ramadan, 55, a Swiss national and the grandson of Hassan al Banna, a founder of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt, has vigorously denied the sexual assault and rape accusations against him and dismissed them as being “a campaign of calumny”.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

On February 16th, Ramadan, complaining of complications from multiple sclerosis and another medical condition, was transferred from his cell to a nearby hospital. His lawyers applied for his release from detention due to his health, but on Thursday this week a Paris appeal court turned down the request after an independent appraisal by doctors concluded his condition was compatible with his continued detention, and he was returned to prison. Ramadan refused to attend the closed-door hearing.

Under French criminal law, a person can be placed in preventive detention if the confinement constitutes the “sole means” of preserving evidence, of avoiding pressure being placed on witnesses, of protecting the person placed under investigation, of guaranteeing their availability to the justice services, to put an end to a criminal activity or because of an exceptional threat to public order.

According to a report by French news agency AFP, Ramadan was placed in preventive detention because the justice authorities decided that there was a risk he would otherwise flee France, and also attempt to place pressure on the two women plaintiffs or others who have accused him of sexual misconduct.

In a detailed investigation by Mediapart published last November, other women spoke out about having had consenting extra-marital affairs with Ramadan, describing his personality as manipulating and controlling, and while the events they recounted would not lead to eventual legal proceedings, they are in stark contrast to his high-profile image as a rigorous Islamic intellectual.

In early November last year, shortly after the rape allegations first emerged, francophone Swiss daily La Tribune de Genève published claims by four former pupils of Ramadan in Switzerland that they were invited by him to have sexual relations during the 1980s and 1990s when they were aged between 15 and 18.

Ramadan in turn filed four lawsuits in Paris and Geneva, two of them for “calumnious denunciation”, another for “defamation” and another for “corrupting a witness”. On his Facebook account, he posted a message last November in which he wrote: “From all sides, whether anonymous or not” he continued, “we read comments that are excessive, racist, anti-Semitic, Islamophobic, dismissive of women, and worse. For more than 30 years I have called for balance, for careful listening, for respectful dialogue and for open and critical intelligence.”

A tireless conference speaker, a visiting professor at universities in Qatar and Morocco and a research fellow with another in Japan, a polyglot and the author of more than 30 books published in French and 15 in English, Ramadan has enjoyed a high profile in many media worldwide. His rise to fame and academic recognition during the 1990s was as the figurehead of a new generation of activists and gave him a large audience across the Muslim world, while he also drew fire from critics, notably in the West, who accuse him of holding an ambiguous position with a covert agenda of radical Islam.

Until this month, publicly-voiced support for Ramadan has remained low-key. In October last year, one of his close associates, Yamin Makri, the founder of a Lyon-based publishing company called Tawhid, wrote an article on website Mizane.info, presented as a website of Islamic news and analysis, in which he denounced that Ramadan “whose anti-Zionist positions are well known” was the victim of “pro-Israeli networks”. But beyond that, the suggestion that Ramadan was the target of a plot was only publicly argued by his brother Hani Ramadan, director of the Islamic Center of Geneva. Meanwhile, the Union of Islamic Organisations of France, the UOIF, (recently re-named Muslims of France), remained silent. “For the UIOF, which is always very cautious, it was politically complicated to support a controversial figure,” said Fatima Khemilat, a doctoral researcher with the Political Sciences School of Aix-en-Provence and a visiting fellow of University of California, Berkeley. “The movement [of support for Ramadan] came from the grass roots, which didn’t understand the lack of mobilisation.”

It was after the public announcement by his lawyers, on February 14th, that Ramadan suffered from multiple sclerosis, followed by the posting online via Facebook of two video recordings of his wife Iman Ramadan, in which she protested his innocence, that the campaign FreeTariqRamadan took off.

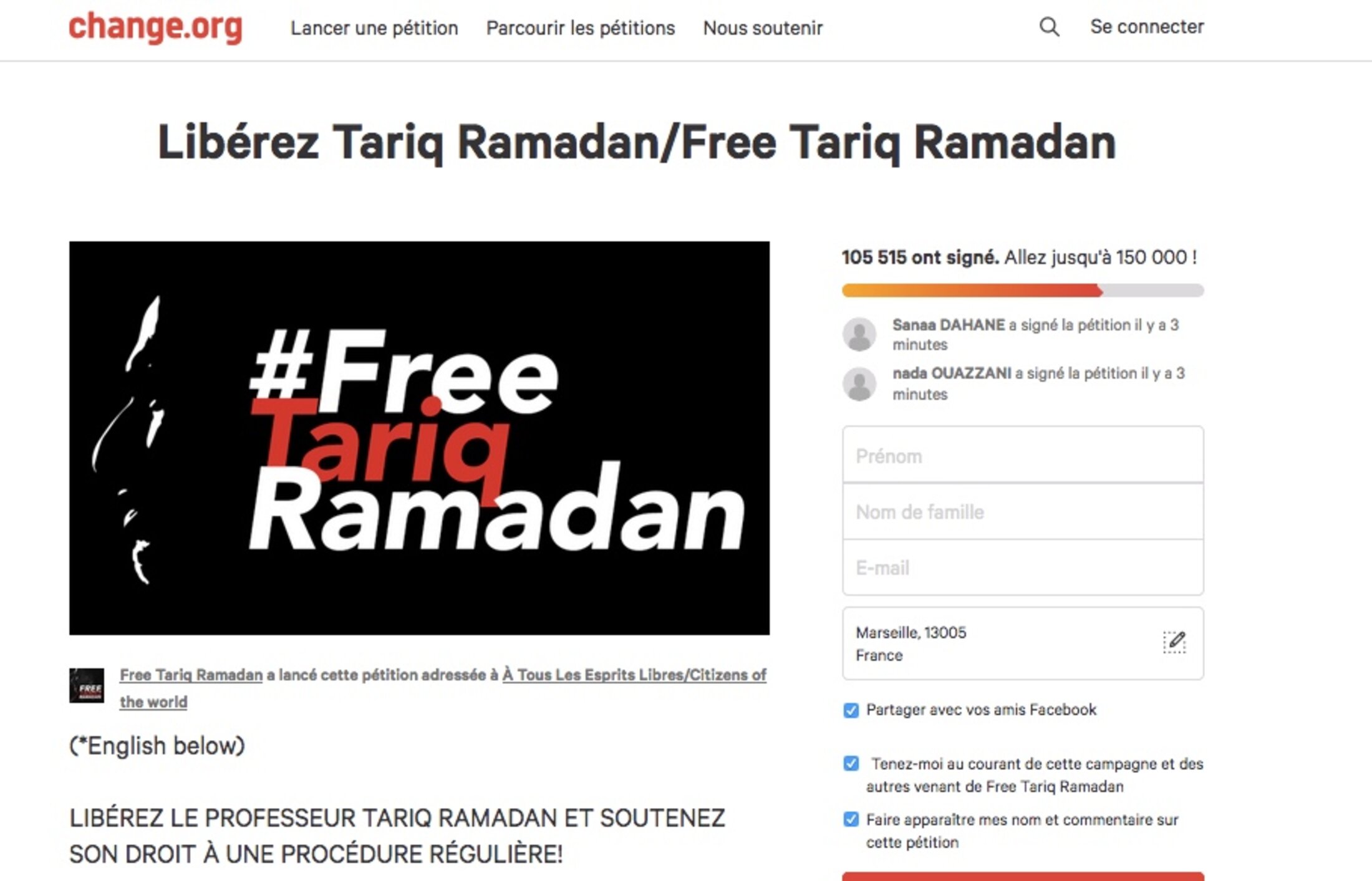

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Launched on January 20th, its online presentation, in English, French and Arabic, declares that: “The Free Tariq Ramadan Campaign is an international movement calling for the immediate release of Professor Ramadan from pre-trial detention and for his right to dignity and due process. There is clear evidence that he was targeted in a politically motivated prosecution masked as a criminal case. There is also little to suggest that Prof. Ramadan will receive a fair trial.” While no names appear on the campaign’s website, several sources have told Mediapart that it is led by Yamin Makri and Siham Andalouci, former kingpins of Ramadan’s movement “Présence musulmane” (Muslim Presence). Two petitions put out by the campaign calling for Ramadan’s release, describing him as a “political prisoner” and claiming the existence of “evidence of undisclosed involvement by high-profile political and judicial figures” have so far attracted at total of 108,000 signatures.

Ramadan’s wife Iman Ramadan, with whom he married in 1986 and has four children, is a former Catholic who converted to Islam, changing her first name from Isabelle to Iman, and who holds dual French and Swiss nationality. Before her recent videos in support of her husband, her last public intervention was in a 2003 interview with a Mauritian magazine. In the first of her two videos, she dismissed “lying accusations” against her husband who she said was the “victim of a media lynching”, and that “the portrait that is painted of my husband in no way corresponds what he is known for”.

She said Tariq Ramadan has for years suffered from a “severe, chronic illness” and had been unable to follow his treatment for it in prison. In the second video, posted on Facebook on February 19th, she cites a medical certificate she said was written by a prison doctor which declared that Ramadan was suffering from “two serious illnesses”, while also condemning “any insult, hate speech, threat addressed to the presumed victims” of her husband.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The video was publicly relayed by the association Collective Against Islamophobia in France (CCIF), which initially accompanied it with a statement demanding that Ramadan be freed and which was soon removed. Contacted by Mediapart, the head of the CCIF, Lila Charef, said she was unable to reply to our questions.

In a lengthy text published on his website, Charef’s predecessor at the CCIF, Marwan Muhammad, also calls for Ramadan’s release from detention “while awaiting his trial” in order to have access to “necessary medical care” and to be able “to prepare his defence in proper conditions”, and arguing that Ramadan’s right to the “presumption of innocence is simply not exercised, on both the level of the media and politically, and perhaps even that of the justice system”. He also wrote that it was necessary “to receive and take into account, with every seriousness, the accounts of the declared victims”, yet he also comments that in their statements, “a certain number of points raise questions”.

The Muslims of France association (the former Union of Islamic Organisations of France), which has long promoted Tariq Ramadan, notably as a guest speaker at their annual conferences, published a statement on February 14th in which they described his continued detention as being “all the more concerning because Mr Ramadan has shown himself to be extremely cooperative with the justice authorities”, and declared that it had “never witnessed the slightest immorality or contradiction between the values promoted by Tariq Ramadan and his behaviour”.

On February 21st, Kamel Kabtane , rector of the mosque in Lyon, and Azzedine Gaci, rector of the Othmane mosque in nearby Villeurbanne, together denounced what they called a “media-political lynching” of Ramadan and calling for his “immediate” release from prison “because of the deterioration of his state of health”. Meanwhile, in a video posted via Facebook, Mourad Hamza, an imam from the southern town of Aix-en-Provence, argued that, according to Islamic texts, “if someone casts calumny upon a chaste woman or a man, he must gather up four witnesses”, otherwise that person is “a pervert”.

Fateh Kimouche, the founder of al-Kanz, a news and opinion website for Muslims, and who is an active blogger, has promoted the FreeTariqRamadan campaign. He told Mediapart it was through empathy with Ramadan’s health problems, Kimouche explaining that his own life has been “destroyed” by the condition fibromyalgia. “There was a feeling of being dumbfounded, which meant that many have not until now intervened,” he said. “I am not a supporter of Tariq Ramadan, but when I learnt that he had multiple sclerosis and that during 15 days he had not received his treatment, I intervened. I would have reacted in the same way for my worst enemy”.

Even a number of Ramadan’s former entourage who ended up distancing themselves from him, and who include Abdelaziz Chaambi, the founder of the association “The Coordination Against Racism and Islamophobia”, have taken a public stand against Ramadan’s detention. Chaambi, who in the early 1990s created in France an association called the “Union of Young Muslims”, and which leant Ramadan a platform for his views, cut off his relations with the preacher in 2009. He argues that Ramadan’s detention is seen by many Muslims in France as “one more” act of discrimination when compared to the treatment given to other well-known figures accused of sexual violence. “His fan club pour out the plot theory, and they come off well because on the other side, the justice system offers no tangible thing to explain his detention,” said Chaambi.

'Tariq Ramadan is extremely powerful'

An open letter published this week on Mediapart’s forum for contributions from outside commentators (“Les invites de Mediapart”), and signed by more than 60 people including several of Ramadan’s colleagues at the University of Oxford, French and American academics, footballers, feminist militants and journalists, denounced what the signatories called “exploitation of the fight against violence towards women” in Ramadan’s case, calling for him to benefit from “a normal judicial procedure” and demanding his “immediate release given his alarming state of health”.

Omero Marongiu-Perria is a sociologist specialised in the place of Islam in France and who has considerable experience with the world of Muslim associations and movements. A Muslim convert in his teens, he was once a member of the French branch of the Muslim Brotherhood, and now takes an outspoken stance against extremist Islamic movements. “Until now, many people preferred to be silent,” he said of Tariq Ramadan’s case in an interview with Mediapart. “But the question of the detention and health has given them a window to intervene without positioning themselves on the issues at stake in the case but about the point that Tariq Ramadan is a targeted man who does not benefit from an equitable procedure.”

“The other strategy is to touch on the apparent incoherencies in the most damaging accounts, those concerning rape, in order to discredit all the others.”

Earlier this month he wrote on his blog that Ramadan’s supporters employ a “suicidal strategy” which he says is mostly driven by the Muslim Brotherhood “sphere”, adding that it was “as if this tribal – or ideological – reflex took the upper hand over any distanced, analytical reasoning”. The text was also published by the website Oumma.com, which claims to be the leading news site of French Islam.

“The symbolic and emotional weight of seeing the fall of Ramadan is too great for a certain number of Muslims, because all that they have built their moral integrity upon, the religiousness, all of that falls,” he told Mediapart. “It is easier to lock oneself away into a tale rather than placing this figure into question.”

The Oumma website published an editorial on February 19th in which it said that “some preachers and militants of associations exploit this terrible affair for base, careerist ends”, and “rise up as sermonizers regarding those who, according to them, do not take up an unconditional fight for the cause of the accused”. The website defended its coverage of the Ramadan case which it said was “as just, transparent and complete as possible”, describing the scandal as one that had “undeniably shaken the European Muslim community in all the diversity of its constituents”.

Fatima Khemilat of the Political Sciences School of Aix-en-Provence and visiting fellow of University of California, Berkeley, says she can understand the doubts about the treatment Ramadan has been handed but she also underlines the ambiguity of the calls for his release from detention. “For me, the manner in which Tariq Ramadan has been treated by the justice system is intrinsically linked to his political stands,” she said. “But is it that one is calling for him to benefit from the same privileges as white, non-Arab men accused of sexual aggression or, on the opposite, that every rape suspect is treated severely by the justice system? It is a true ethical question. There is a tendency to forget that Tariq Ramadan is extremely powerful, that he has money, that he has been a professor at Oxford, and backed by Qatar.”

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse