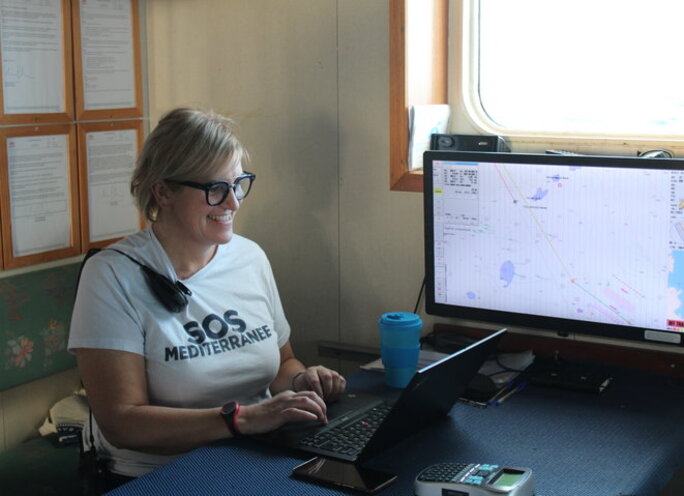

“It’s very good news, I’m happy things went quite quickly,” said Luisa. She is coordinator of search and rescue operations, seated at an office on the bridge of the Ocean Viking, flagship of the French-based humanitarian organisation SOS Méditerranée.

It was late on Sunday afternoon when Luisa learnt that the ship, operating in the southern Mediterranean, was finally allowed to dock in the port of Augusta on the Italian island of Sicily, after initially being redirected to Libya by the Italian Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre. From previous experience, she knows that migrant rescue ships can be stranded for long periods at sea while waiting for permission to disembark their passengers, as illustrated by the notorious 19-day standoff involving Spanish NGO vessel Open Arms in August 2019.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The Ocean Viking resumed patrolling in international waters off the Libyan coast on January 11th, sailing from the French port of Marseille, where SOS Méditerranée is based. It had previously been blocked five months in the Sicilian port of Porto Empedocle after the Italian authorities ordered it to undergo a costly refurbishment, officially to bring it in line with safety norms. At the time , SOS Méditerranée described the Italian move as “blatant administrative harassment [...] aimed at impeding our life-saving work”. The boat was released on December 21st, after it was certified to carry 286 passengers (previously this was limited to 41).

Mediapart joined the Ocean Viking for the journey south from Marseille. Over a 48-hour period at the end of last week it rescued a total of 374 migrants attempting the perilous journey north to Europe in overcrowded rubber dinghies. Most were from sub-Saharan Africa, and included 165 minors, 131 of whom were unaccompanied, according to SOS Méditerranée.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Between January 1st and January 26th this year already, 105 migrants have died attempting to cross the Mediterranean, according to the “Missing Migrants” project of the inter-governmental International Organization for Migration.

It was after four separate rescue interventions that the Ocean Viking began heading back north on Saturday towards Malta and Sicily in the hope, but uncertainty, of receiving authorisation to dock on one of the islands.

“I made a first request to the Libyan authorities, with Italy and Malta copied in, as soon as the first rescue was carried out on Thursday January 21st,” explained Luisa. “We contact Libya because the rescue was carried out in its part of the SAR [Search and Rescue] zone. It is therefore supposed to be in charge of the coordination even if, in the event, that’s not the case.”

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Luisa keeps the Libyans informed at each stage of the rescue operations, when the Ocean Viking receives an alert about a dinghy in distress, when it sends out its rapid rescue craft and when the rescue operation is concluded. “After that I send a maritime incident report, always keeping the Italian and Maltese authorities copied in,” she said. “It represents a lot of email communications and it’s very time consuming, but we have to do it because the Libyan Search And Rescue zone is recognised by law.”

In previous operations, the vessel has been told to disembark its passengers in ports in Libya but the NGO declines to do so on the basis that theses do not meet the criteria for being “safe ports”. The notorious conditions in which migrants are detained and kidnapped as slave labour in the war-torn North African country have been widely documented. Last week, the Libyan Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre (MRCC) did not reply to the SOS Méditerranée messages.

Between January 22nd and 23rd, by which time the Ocean Viking had rescued 374 migrants, Luisa sent out four more messages to the authorities in Libya, Italy and Malta. On the evening of January 22nd, the Italian MRCC finally answered, indicating that because it had not coordinated the four rescues, the Ocean Viking should return to the country with responsibility for the SAR zone where they happened – in this case Libya.

During the day on Saturday, January 23rd, the Italian Coast Guard met the Ocean Viking to take off a pregnant woman migrant whose condition placed her health at risk. Then on Sunday, as the vessel waited in waters between Sicily and Malta, the weather turned bad. “When I have no reply, it’s a deafening silence,” said Luisa, who is herself Italian. “A painful silence.”

The waves rose to around two and a half metres, slapping into the side of the boat and showering the deck where some of the rescued migrant men were kept because there was no other space for them. The crew brought out wooden pallets to offer some protection from the water. As a queue formed the following day for the distribution of breakfasts, a number of the migrants looked the worse for fatigue and sea sickness, for which the boat’s midwife handed out little blue pills to offer some relief.

It was in the middle of the afternoon on Sunday that Luisa sent out yet another request to the Italians and Maltese for urgent permission to dock. “I had just a half-hope because the political situation in Italy is unstable at the moment, and all that is very political,” she said. “But I finally received a call from the Italian MRCC at 4.20pm with indications for disembarking in the port of Augusta in Sicily.”

At 5pm, Karim, in charge of coordinating the reception of migrants aboard the Ocean Viking, and Riad, its “cultural mediator”, announced the good news to the passengers through a megaphone. The crowds on deck exploded with joy. Women, men and children broke into applause, singing and pumping the air with their fists, laughing with happiness. “It’s a real relief,” said crew member Laurène, who barely contained her emotion. “Libya, that’s over,” she said. “I can’t believe it, it’s like a dream.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

“I saw a man, lying down, who was crying,” said Matthieu, the boat’s deputy coordinator for the search and rescue operations. “You could feel that the weight of everything was lifted, he was submerged in emotion. It’s amazing how people can react differently.” Another crew member, Hannah, brought out from the infirmary tomtoms, decorated in African colours, handing them around the migrants who began tapping on them in celebration.

“One is always expecting the worst, even if it’s only for [the sake of] our mental health,” added Luisa. “It has been the case that it takes a very long time before we obtain a safe port to disembark, like during the last sortie. So it’s best that everyone be prepared. I think the fact that we’re in winter and that there were so many people aboard helped. I would also like to believe that the authorities are thinking of their welfare, but you can’t really know what is going on underneath it all.”

On Monday morning, the migrants disembarked at Augusta with the hope of beginning new lives. The ill, the injured, the pregnant women and the children among them would be given priority to leave the ship. All will remain in quarantine for two weeks. For the time being, SOS Méditerranée does not know whether the group will remain in Italy or if they will be admitted, in quotas, into other European Union countries.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse