From Mediapart's special correspondent Carine Fouteau, aboard the Icelandic coastguard vessel Týr.

The freighter appeared suddenly on the radar of the Týr, and its route suggested that it was out of control. It was Thursday, February 5th, and weather conditions in this central part of the Mediterranean Sea were poor, with howling winds and a strong sea swell.

The Týr is a 71-metre long Icelandic coastguard vessel, now engaged in patrolling in the Mediterranean Sea under the operational framework of Frontex, the European Union (EU) agency which was set up in 2004 with the principle mission of securing the continent’s exterior borders from illegal immigration and terrorist intrusion.

The Icelandic vessel is more specifically part of operation ‘Triton’, a Frontex-coordinated mission in which vessels and aircraft provided by EU member states provide support to the maritime surveillance activities of the Italian authorities, who have central command of the operation. The Týr has a crew of 17, accompanied by an Icelandic police officer.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

On the morning of February 5th, I joined the Týr as it raised anchor from Pozzallo, in Sicily, to reach the zone where the freighter had first been spotted – a ten-hour journey, despite the patrol vessel’s swift speed, south from the Ionian Sea which separates the heel of Italy from Greece, and into the wider Mediterranean.

It was at about 10 p.m., in the grey darkness ahead of the Týr, visual contact was made when a black shape emerged on the horizon. But attempts to raise radio contact with the freighter brought no response. A plane had earlier been sent to investigate, but its study of the boat had found no sign of anyone on deck.

Closer to, it was clear there was no activity from its engines. Above the empty decks of the Zein, a 170-metre long Panama-registered boat, a few high-powered spotlights lit the bridge. There was still nobody in sight. The Zein rose and dropped with the swell, resembling so many other ghost ships recently found abandoned in these Mediterranean waters, between Italy, Greece and Malta, in which hundreds of Syrian refugees were found stashed below deck.

Just like the Ezadeen, which the Týr rescued in early January after people smugglers abandoned the controls leaving 360 Syrians to their fate, the Zein is a rusting 37-year-old cattle freighter whose last port of call was believed to be in either Turkey or the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

Despite the absence of anyone on its decks, the Italian authorities suspected that the Zein may be carrying migrants in its hold. There was also the possibility that the people smugglers were still aboard, waiting for the boat to reach Italian waters before abandoning ship. Italian coastguard and navy vessels were sent to join the Týr.

The Zein was in a zone south of the Ionian Sea that lies more than 100 nautical miles from the Sicilian coast, in international waters situated between Italy, Greece and Malta. It is a busy maritime sector, where cargo, military and tourist traffic constantly criss-cross the waters.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The precise spot where the Zein lay drifting was officially a Maltese Search and Rescue (SAR) zone, which meant that the Maltese authorities would be responsible for its rescue if it was established that it was in peril. But the Maltese decided that because no SOS had been sent out from the freighter it was impossible for them to intervene. It was after midnight when the Maltese authorities contacted the Italian maritime rescue coordination centre in Rome (MRCC) to say that contact with the boat had at last been established, and that the crew of the Zein were repairing the freighter’s engines. Once this operation was completed, the message added, it would continue its route to Las Palmas, in the Spanish Canary Islands.

That announced the end of the operation for the Týr, which turned back to its base in Sicily despite all the evidence that the Zein was carrying migrants destined to be later abandoned in the Italian SAR zone.

There was also a recent precedent: at the end of December, the Blue Sky M, a freighter travelling west across the Mediterranean from Turkey, was in Greek-controlled waters when one of the boat’s passengers used a mobile phone to call for help, claiming there were armed men aboard. After radio contact was established by a Greek coastguard vessel with the freighter’s crew, who reported no mechanical problems, it was allowed to continue its route. But it was later boarded by the Italian coastguard who discovered more than 900 clandestine, mostly Syrian migrants on board. About 100 were suffering from hypothermia. The Blue Sky M had been abandoned by its crew and its motors were blocked on a preset route that, without the coastguard intervention, would have seen it crash onto Italian shores.

From on board the Týr that February night, the scene was surrealist. An armada of European navy, coast-guard and police vessels surrounded the Zein, unable to verify what lay behind its suspicious behaviour. “We are under the command of Rome,” explained the Týr’s captain, Einar Valsson, 49, who began his career in the Icelandic coastguard at the age of 15. “We can’t go on board because no distress call was issued. We are not allowed to intervene in international waters.” But what if the migrants thought to be onboard were in danger? Would they, abandoned to their fate by the crew, know how to send out an SOS? “We obey orders,” answered Valsson.

The following morning, February 6th, a new alarm was raised, and the Týr was sent back to shadow the freighter after it was established that it was not following its declared route to Las Palmas. But a few hours later, the order was changed again and the Týr given a “definitive” stand-down – until the next time.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Captain Valsson, always ready for the worst, lets little emotion show in his face. Except when he recalls those lives he and his crew have saved. That is his pride. Since operation Triton was launched on November 1st 2014, it has saved 17,999 migrants from danger at sea, and 2,000 of that number were directly rescued by the Týr. The remainder was picked up by either the Italian coastguard or merchant vessels. The latter are bound by maritime law to assist a vessel in trouble if they are the nearest to it, and face severe penalties for not doing so.

Over the past 20 years, the clandestine migrant traffic across the Mediterranean has steadily risen, reaching more than 200,000 in 2014 alone. According to figures released by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the inter-governmental International Organization for Migration, more than 25,000 migrants have died attempting to cross the Mediterranean over the past two decades. At least 3,400 deaths occurred last year alone.

Earlier this month, during the night of February 8th-9th, the Italian coastguard found at least 29 people had died of hypothermia on board an inflatable boat carrying more than 100 migrants that got into difficulty off the coast of the island of Lampedusa. On February 11th, the UNHCR announced that about 300 migrants from sub-Saharan Africa had died after two boats, part of a four-boat clandestine convoy from Libya, sank off the Italian coast.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Over recent months, the maritime fleet coordinated by Frontex, and which is made up of vessels from EU member states, has witnessed a clear switch in the departure points of people-smuggling traffic, from Libya to Turkey where massive numbers of Syrian refugees are crossing the common border in an attempt to flee the carnage of the civil war in their country. People smugglers are demanding between 4,500 euros and 6,000 euros per person on the one-way crossings from Turkish ports, the most often aboard ageing merchant vessels that have no legal commercial future. About 15 examples of this clandestine transportation method have been recorded since last autumn.

'In their eyes I saw everything they went through'

Enlargement : Illustration 6

The Týr, which once served in the 1975-1976 Cod War and which has been extensively refurbished since then, is a military-grey, patrol vessel equipped with infrared cameras and a rapid-intervention inflatable craft. In its operational zone around Italian, Greek and Maltese waters, the rust-bucket freighters have become its new target. The Týr was on duty when the Ezadeen was spotted at about 80 nautical miles off the Calabrian port city of Crotone, on the southern tip of the Italian peninsula, during the night of January 1st. Registered in the West African state of Sierra Leone, the freighter had that night been abandoned by its crew after an engine failure. Contacted by radio by the Italian authorities, there was initially no response from the vessel until a woman passenger finally answered, pleading: “We are alone, there is no-one, help us.”

Andri Johnsen, 26, who has served in the Icelandic coastguard since the age of 18, was at the helm of the rapid-intervention dinghy sent out by the Týr to investigate. “It was night,” he recalled, “conditions were very hard, a rough sea and bad winds.” Battling the elements, he and his crewmates approached the silent, drifting freighter. Inside were 360 Syrian refugees.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

When the migrants aboard saw the Icelandic coastguards climb aboard, they rushed towards them, many with outstretched hands, begging them for help. “They were afraid that we were going to leave,” said Johnsen. “They were anxious. They asked for water, food, they tried to get our attention. We had to reassure them. We told them we were going to stay, we were here to help. As soon as they understood it, they calmed down. They felt reassured. They went back to their seat. They knew they were safe. We were going to take them to Italy.”

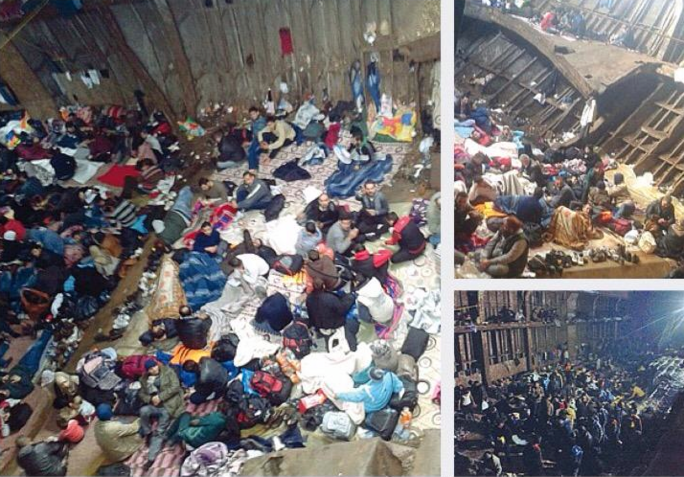

Inside the freighter, it was pitch-dark. In the stabbing light of their head-torches, the Icelanders discovered the horrific conditions aboard. “It was unbelievable,” continued Johnsen. “All these people crowded. I would never have imagined to live something like this. Three hundred and sixty people, families, women, children, babies, old people, pregnant women. We saw babies who couldn’t carry their head. Some old women couldn’t walk on their own. They were exhausted. It seemed they went through so many things. They said they had travelled six to ten days in the hold without moving. It was freezing.”

Enlargement : Illustration 8

The migrants were huddled in dampness, amid a temperature that night of 10° Celsius. “They said they were hungry and thirsty, Johnsen said. “I was surprised because they all carried suitcases, with all their life in it. Some of them had blankets or extra clothes on. Some of them had home-made lifejackets. Some had almost nothing. They stayed on boxes. Those usually used for animals. They stayed in the dark for hours, with huge waves and feeling sea sick. Some of them were sick. The bathroom? They did it where they could. It was so dirty.”

Enlargement : Illustration 9

The Icelandic crew sought out a passenger who could serve as an interpreter in English, and distributed bottles of water and concentrated food for the children. The passengers who were ill were identified, and while the coastguards found no indications of passengers having suffered from physical violence, many were suffering from advanced conditions of stress and fatigue.

The sea was too rough to transfer the migrants to the Týr. Instead, escorted by Italian navy vessels, the Týr towed the Ezadeen to the Calabrese port of Corigliano, where the Syrian families finally disembarked. The memory of that moment is certain to stay with Andri Johnsen a long time. He had already saved migrants from the seas, but never from a boat of that size. “It’s hard to put words on it”, he said. “It’s hard to describe. I couldn’t expect something like that.”

“In their eyes I saw everything they went through,” recalled the young coastguard. “It was hard to sleep because of the work, the rescue, it was hard. It was hard but I was proud, so proud, to be useful […] All of them, almost all of them, came and said thank you. They shook hands.”

Asked if he thought they had embarked on the perilous journey knowing the dangers they faced, he answered: “They knew it was not going to be like holidays, but they didn’t expect it was going to be hard like this.”

'We don't do push-backs, they're forbidden'

Although serving for Frontex, an agency whose mission is to secure EU borders, Johnsen says he certainly doesn’t feel like a policeman. “Not at all,” he insisted. “I am a coastguard, I save lives, that’s all." Captain Einar Valsson is of the same opinion. While he was not on duty when the Týr pulled the Ezadeen to safety, he has lived through a number of epic rescues. One of the most recent was on December 9th last year, when the Týr saved 408 people aboard another old freighter, found drifting without fuel. The passengers, who had spent the previous two days without food or water, were fed and looked after on board the Týr. “It was heartbreaking to see the smiles return to their faces again,” he said, adding: “Nobody died this time.”

Captain Valsson insists that his mission within operation Triton is simply to save lives, responding to criticisms from some migrants rights groups who argue that Frontex joins surveillance activities to its rescue mission. One of them, the Migreurop Network, founded a campaign with other rights groups called Frontexit, calling for an end to the Frontex operations and claiming that “the mandate of Frontex is incompatible with human rights” (see more here). They argue that the agency is transforming Europe into a fortress, leading to a situation whereby migrants take increasing risks to reach the continent.

“When people are in distress, we come and help,” said Valsson. “If we see vessels loaded with migrants without asking for help, we follow them and take them to land.” The issue is blurred in the terminology used by Frontex, which describes such incidents as “interceptions”, suggesting a certain form of policing clandestine immigration. “We don’t identify people, we don’t take fingerprints,” Valsson stressed. “What we do is take them to bring them to shore where authorities take them in charge.”

Enlargement : Illustration 10

But what happens during this process of taking migrants in charge? Frontex spokeswoman Izabella Cooper was present aboard the Týr during its mission off Pozzallo earlier this month. She underlined that under international law every individual has the right to leave their country to seek asylum elsewhere, and each individual’s request for asylum must be given proper consideration. Asked if that was the case with the swelling numbers of boat people crossing the Mediterranean, she answered: “It is not our responsibility. We cannot answer for member states.” She refused to give precise details on the Týr’s operational zone because, she said, it could serve the interests of the people smugglers. “Our mission is to save lives,” she said. “If we receive a call for help beyond our zone of intervention of course we go there. We could go all the way to Libyan waters if need be.”

With a monthly budget of 2.9 million euros, operation Triton has taken up the relay from Mare Nostrum, the Italian military mission of sea patrol and rescue that was set up following the October 2013 Lampedusa tragedy when more than 360 migrants died when their boat sunk off the coast of the southern Italian island. Between October 2013 and October 2014, when it was wound down by Rome for lack of budgetary support from the EU, Mare Nostrum, which cost a monthly 9 million euros, saw some 85,000 migrants plucked from peril at sea.

Enlargement : Illustration 11

Triton covers a smaller area than Mare Nostrum’s brief, and operates with fewer and smaller vessels. Following the hundreds of deaths of migrants earlier this month close to his island, Lampedusa mayor Giusi Nicolini claimed the tragedy would never have happened if Mare Nostrum had been maintained.

While Frontex operations undoubtedly save many lives, their initial brief is the surveillance of borders. “We must detect, in one way or another, all the people entering the EU,” said Frontex spokeswoman Izabella Cooper, speaking at a table inside the Týr’s canteen. In the case of operation Triton, that mission is given to the participating aircraft and not the naval vessels, she said.

Once on dry land, migrants are questioned for information about the people smugglers and, according to Cooper, 75 traffickers have been arrested since Triton was launched in November 2014. Asked about the expulsion of rescued migrants, Cooper said such practices have “nothing to do” with Triton. “We hand people over to the authorities,” she insisted. “It is they who decide about the repatriations. Frontex sometimes organizes these, upon the request of states, but that represents just 2% of the total number of repatriations.”

Enlargement : Illustration 12

The issue of the divide between policing and rescue is a sensitive one. During its ten years in existence, Frontex has not always minimised its role as an EU border guard. Reports published by rights groups such as Human Rights Watch, Migreurop, FIDH and Amnesty International have recorded numerous witness accounts of ‘push-back’ operations, an illegal process of blocking and sending back migrants before they can request asylum. Most of these incidents happen on dry land, notably on border areas between Turkey, Greece and Bulgaria.

But the agency may also be associated with incidents at sea. According to Maltese newspaper Malta Today, in June 2009 a German helicopter taking part in a Frontex-coordinated operation, Nautilus IV, based in Malta, spotted a vessel carrying 75 migrants heading towards Lampedusa. Subsequently, an Italian coastguard patrol led the migrants to a Libyan navy vessel which returned them back to Libya. Such practices are contrary to international law, even when they are conducted in international waters. This was confirmed by a ruling of the European court of Human Rights in February 2012 in a case brought by 24 Somali and Eritrean migrants who were among 200 intercepted at sea by the Italian navy and forcibly sent back to their departure point in Libya. The court found that Italy had violated their human rights and placed their lives in peril in Libya.

“Push-backs, they’re forbidden, we don’t do them,” said Frontex Executive Director Fabrice Leggeri, interviewed by Mediapart when he visited the crew of the Týr in Pozzallo. “We coordinate the means provided by the member states,” he continued. “We detect illegal entries and we identify people to help dismantle the criminal organizations who stash hundreds of people on boats to the peril of their lives.”

Meanwhile, the missions accomplished for Frontex since 2010 by the Týr’s captain Einar Valsson read like a chronology of maritime migratory fluxes. Beginning with Senegal, from where hundreds of thousands of sub-Saharan African migrants try to reach the Spanish Canary Islands on flat-bottomed boats. Then the Strait of Gibraltar, where migrants cross on inflatable dinghies. The Týr was later sent to patrol the waters off Crete, to where migrants arrived in fishing boats and small yachts, before its current mission based in Italy, hunting the rust-bucket freighters that depart with much larger human cargoes from Turkey.

Enlargement : Illustration 13

The sea routes of the migrants – and the people smugglers - change one after the other, and to a certain degree this is because of the surveillance by Frontex. Týr crewman Rägnvaldur Kristinn Ulfansson, 28, has served on the Icelandic patrol ship for almost five years. He said he has observed that the numbers of migrants taking to the seas appears to be ever-rising. He did not want to talk about his experiences patrolling off Senegal and Spain, which were bad memories, preferring, like his crewmates, to remember less dark events, those in which no-one died.

Two days after the interception of the Zein, the Panama-registered ghost ship found by the Týr drifting in the central Mediterranean, its position could be found on the website MarineTraffic.com, which tracks the movement of vessels in real time. It was positioned off the coast of Tunisia, after having passed close to the island of Lampedusa, apparently on a course that might just take it to Las Palmas. Or not.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse