It has become the latest technique used by people traffickers to transport desperate migrants across the Mediterranean Sea and into Europe; cramming them into old rusting cargo ships and leaving them to their fate before the crew members risk getting caught. Early last week the Moldova-registered cargo vessel Blue Sky M was apparently abandoned by its crew and left to its fate in the Aegean Sea. On board Italian coastguards found some 800 Syrian and Kurdish migrants and refugees, left without supplies, water or shelter.

“A massacre was avoided, more than 900 [sic] migrants were saved on a ship on which the engine was locked and which was heading for the coast of Puglia [region of south-east Italy],” said Italian coastguards on Wednesday. Had they not intervened the ship, whose steering had been set towards the coast, would have foundered on rocks. Early reports said all the crew had abandoned ship, though later there were suggestions that at least some had stayed on board and mingled with the migrants in a bid to escape detection by the authorities.

According to Italian media reports from Gallipoli where the migrants were taken, the passengers included around ten pregnant women and thirty children, and were suffering from hypothermia and dehydration. Four had died on the journey. The Italian coastguards had been alerted to the presence of the ship by an SOS from the vessel off the coast of Corfu, which claimed that there were “armed men” on board. The other merchant vessel discovered last week was the Sierra Leone-registered cargo vessel the Ezadeen. This was in difficulty in the Aegean Sea and, again, its crew appeared to have abandoned it, leaving 359 Syrian migrants on board. It was later towed to safety at Corigliano Calabro in southern Italy. Both ships are thought to have come from ports in Turkey in what marks a change in tactics used by people smugglers, who until now have focussed on the longer and more perilous sea crossing from Libya in North Africa.

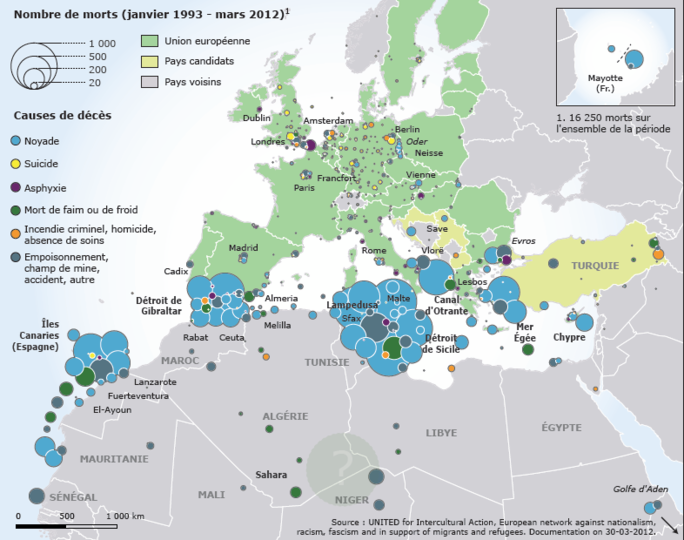

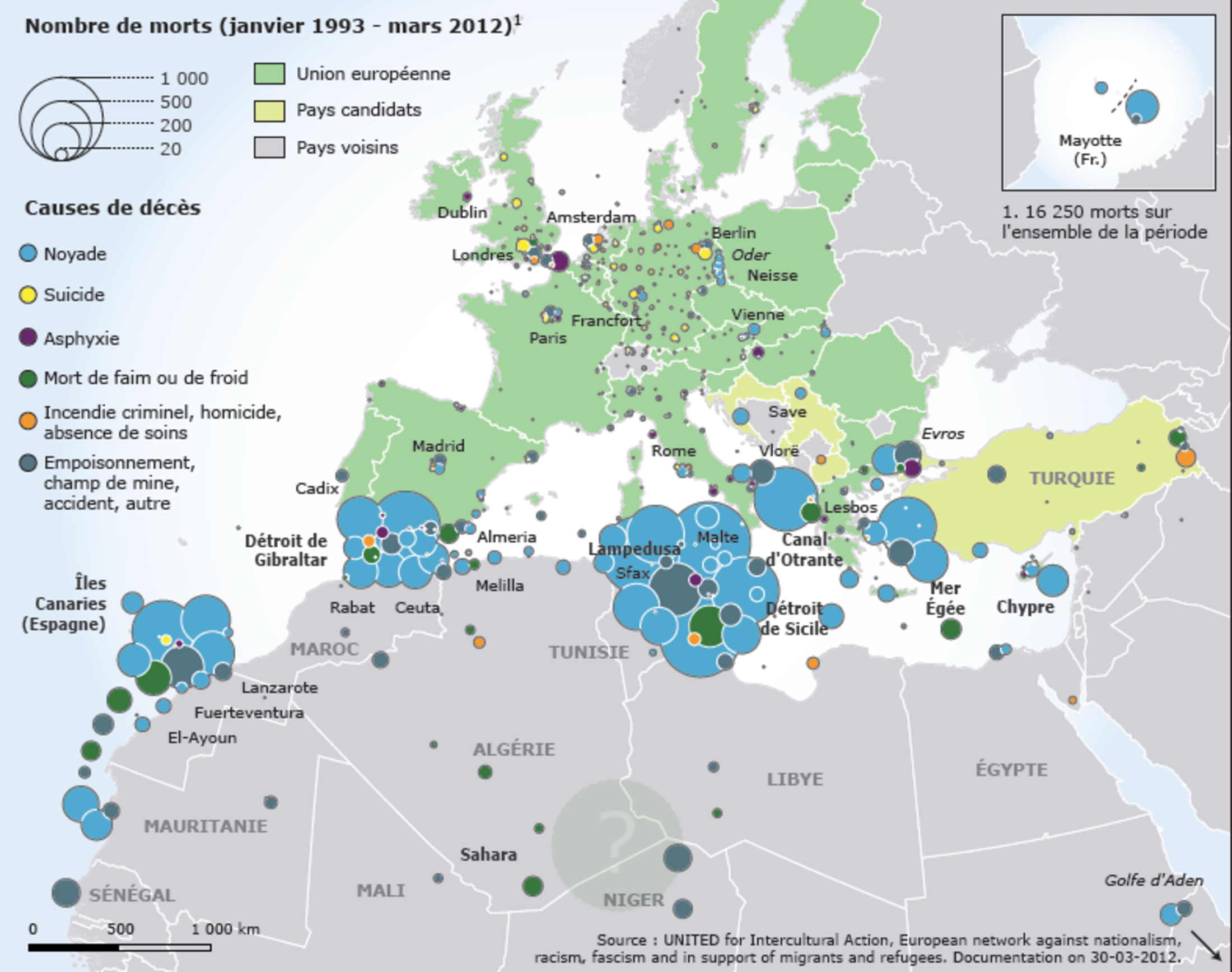

Thanks to the large numbers of people wishing to leave war-torn countries in the Middle East and Africa, people trafficking has become an established and increasingly lucrative business. The trade now generates billions of euros in profits each year and has recently become much more 'professional'. The risks for the migrants, meanwhile, have become even greater. This year for the first time in recent years there was no winter pause in the migration and clandestine journeys across the Mediterranean have continued despite the poorer weather and sea conditions. As a result entire families have been crammed onto overloaded boats at serious risk of sinking. On December 10th the UN refugee agency the UNHCR stated that a record number of more than 207,000 people had crossed the Mediterranean since the start of January 2014. This is three times more than in 2011 when the numbers were already boosted by the 'Arab Spring' revolution in Tunisia. It has become the most deadly migration route in the world; at least 3,419 people lost their lives trying to cross the sea in 2014.

The UNHCR points out that for the first time in 2014 it was people from war-torn countries – chiefly Syria and Eritrea – who made up the majority of people on the migrant boats. In other words the poverty that has spurred generations of sub-Saharan Africans to leave is no longer the main source of migrants.

Another change is that many of the current migrants are entire Syrian families (see this video report in Italian by newspaper Corriere Della Sera from September 23rd, 2014, on a rescue operation). Many of these come from the middle classes and often have more money than other refugees. After the arrival of the Ezadeen in Italy, one local official said the Syrians on board were of a “certain economic means”. The official added: “They were well dressed.” Doctors, engineers and business people, these new migrants have refused to be conscripted into Syrian president Bashar Al-Assad's army or join the ranks of Islamic State. The traffickers take advantage of the presence of this wealthier clientèle by raising prices. In exchange for thousands or even tens of thousands of euros they hold out the prospect of being taken to Germany, Sweden or Holland, the three leading destinations.

According to estimates by Frontex, the European Union agency that helps manage Europe's external borders, with migrants and refugees paying up to 2,000 euros each for their passage, a single boat trip with 450 passengers on board can net the smugglers close to a million euros. Over a year the total earnings for the traffickers runs into several billion euros. The head of the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), Yury Fedotov, recently cited the figure of 7 billion dollars (5.6 billion euros) as the money made yearly by people traffickers between Africa and Europe and Latin America and North America.

However, the fact that the crossings are illegal makes this a difficult area to get reliable information. The sources of information are scarce: occasional confessions from traffickers, witness statements from migrants and analyses from non-governmental organizations and international bodies. However, at their trials in recent months some people accused of trafficking migrants have been forced to describe their activities. One such person is 33-year-old Tunisian Karim El-Hamdi, who was arrested at the port of Pozzallo in Sicily having acted as skipper of a boat full of migrants. His testimony, published by various websites in June 2014, shows how the trafficking business has changed with the arrival of wealthier migrants and refugees from Syria.

“The Syrians buy everything. That has pushed the traffickers to offer more,” he told the Italian authorities. He lists all the “services” that the traffickers make the migrants pay for. The basic price for getting a place on the boat – usually an old fishing vessel that is no longer considered seaworthy enough for its original purpose – varies between 1,000 and 2,500 dollars. Everything else is on top, said Hamdi: 200 dollars for a life jacket, a hundred dollars for bottles of water and tins of tuna, 200 dollars for blankets or waterproof clothes, and 200 to 300 dollars for a place in “first class” – meaning the boat's deck. Being put in the ship's hull is regarded as “third class”. A call of just a few minutes on a Thuraya satellite phone can cost 300 dollars, while supplying the mobile phone number for special pick-up services that will smuggle migrants to the Italian border can cost several thousand dollars.

The various smuggling networks organise themselves according to this new “demand”. Frontex believes that Libya is one of the hubs. The “criminal gangs” there have taken control of the country to the extent that no one can move without them. According to the agency they recruit former migrants for their knowledge of local languages and to put them in touch with potential migrants. The trade has become big business both in the Libyan capital Tripoli and in the coastal towns from which migrants leave. The migrants are charged a great deal for their accommodation in crumbling houses, run-down hotels and decrepit outhouses, for their food and for their passage.

'I’m not a criminal, I provide a service'

The heads of the trafficking networks look for intermediaries who are able to provide the necessary transport. The result is that the traffickers who appear before the Italian courts are often low-level figures. The Tunisian Karim El-Hamdi, for example, claims that he became a people smuggler by accident. Himself a migrant looking to get to Europe, he was in a café in Tripoli when he was offered 1,500 dollars to skipper a boat. Like him, lots of migrants capitalise on their skills and knowledge during their journey. The greater the risk, the more it pays. For example at Calais, the French port used by many migrants seeking to get to Britain, opening and closing lorry doors can earn someone a few euros. In Paris, meanwhile, buying train tickets for your compatriots is seen as a way of earning a little cash. Sometimes this leads to the migrant being picked up by the police, and on occasions earns them a conviction for aiding and abetting trafficking.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

At sea the traffickers have several options when it comes to avoiding arrest. One is to abandon the boat by taking to the lifeboats before it is intercepted, another is to stay on board and pass themselves of as migrants. That is what another Tunisian, Khaled Ben Salem from Sfax, tried in vain to do; he is accused of being the captain of a boat that sank off the Italian island of Lampedusa on October 3rd, 2013, with the death of 363 people. According to journalist Fabrizio Gatti from Italian news magazine L’Espresso, that boat trip alone earnt the people smugglers around 760,000 dollars (about 646,000 euros), once “costs” had been deducted. These expenses include the fishing boat itself, fuel reserves, transporting the passengers in lorries and paying the boat's crew. Children are also increasingly being used to crew boats to reduce the severity of prison sentences.

A different type of people smuggler was interviewed in the summer of 2014 by The Guardian newspaper at his flat in the Libyan port city of Zuwara close to the Tunisian frontier, where the majority of illegal crossings start. He does not go on the trips himself, preferring to remain on dry land to organise the voyages to Lampedusa, the Italian island which is the closest part of Europe to Libya. The trafficker, who is still operating, explained the rationale behind his business, which nets him a least a million dollars a month. Though he has been a people smuggler since 2006, he owes his recent prosperity to the collapse of the state since Muammar Gaddafi's fall in 2011, with the maritime and land borders having been left without much surveillance. “So far, none of the boats I filled with people have sunk. This gives me good credit as a trafficker among the agents,” he told the newspaper. “I am not a criminal. I provide a service,” insisted the smuggler, who is in his 30s.

Yet it is a merciless “industry”. The Frontex agency says that the growth in the number of crossings has been accompanied by a growing level of brutality on the part of the traffickers. For example, a boat was apparently deliberately sunk off the coast of Malta in early September 2014 after the passengers – Syrians, Palestinians, Egyptians and Sudanese – refused to be transferred into smaller craft. Five hundred people drowned. Migrants say they are often beaten while there are reports of one man being stabbed to death. Witnesses have also described shots being fired over migrants' heads and bodies of dead passengers being thrown overboard.

But as is becoming apparent, Libya is no longer the only country being used by traffickers as a springboard to sending people to the European Union. As the two recent examples of the cargo ships show, Turkey is increasingly popular as a base for people smuggling. Indeed, according to Frontex, Turkey is often preferred to Libya as boat journeys from the latter are increasingly seen as too dangerous. More than 815,000 Syrians have found refuge in neighbouring Turkey since the start of the civil war in Syria. Some stay, but others seek to continue their journey, to the benefit of the traffickers.

Districts of Istanbul – such as Aksaray and Tarlabasi – have developed networks based on the trafficking trade, with hotel rooms providing accommodation and migrants working on the black. Since Greece built a wall along part of its land border with Turkey, near the River Evros, the migrant route has largely switched to the Aegean Sea. Many of the departures are from the ports of Izmir and Marmaris in inflatable boats. As the crossing is shorter and less dangerous than from Libya, the prices are higher: according to the Brussels-based news site Equal Times the cost ranges from 2,000 to 3,000 euros per person.

But even before last week's dramatic events, Frontex had already been warning of a sudden change of tactics by the people smugglers. They are now using old cargo vessels sailing out of the port of Mersin in south-east Turkey, which until December 2014 had a ferry link with Tartus in Syria and still has a ferry service with the Syrian city of Latakia. The people smugglers cram the migrants into these 75-metre-long cargo vessels which are then abandoned at sea until help arrives. On Saturday December 20th, 800 migrants were rescued off the coast of Sicily after the crew had set their vessel to autopilot and abandoned ship.

The smugglers make millions from trips on these larger vessels, as these passengers are charged a minimum of 6,000 euros a person, on top of 'extras' they have paid, such as the 16 grammes of gold they hand over to militias to enable them to leave Syria. With on average 6,000 people on board each such vessel, a single crossing can net smugglers around 3.6 million euros. “These boats – which are sometimes equipped with Russian crews – are expensive and difficult to find but the demand is so great that it makes this method profitable,” says Antonio Saccone, head of operational analysis at Frontex. “It shows how powerful and sophisticated these networks have become,” he adds.

Epic journeys in search of freedom – and safety

The people smuggling industry is concentrated around Turkey and Libya, the two main entry ports to Europe. But the smugglers begin their work at the point at which the migrants leave Syria, with the frontiers being closed on regular occasions, and continues until they are inside the Schengen area of Europe – where internal border controls have been abolished – to allow the passengers to reach their final destination. There is no one network which takes charge of the migrants right throughout their journey; instead, the traffickers control different stages along the way according to their nationality, the languages they speak, their own networks and their experience.

A migrant's journey can last months or even years; at each halt they have to get by and make money as best they can. They travel on foot, by lorry, in boats and even by plane for those who have the means to pay for the various false identity documents they need to authorise their stay.

Families do not always make the journey together: some begin the voyage alone and then wait for their family members to join them. A report in The New York Times on November 29th, 2013, described the epic voyage of one Syrian woman, who left with 11,000 dollars in her pocket, and who at each step of her journey had to deal with the legal demands of the different countries she crossed as well as the demands of the traffickers. Travelling via Egypt, she eventually reached Sweden. Meanwhile in August 2014 Newsweek retraced the Balkan journey of a man called Murat, who eventually made it to Austria having crossed the borders of Macedonia, Kosovo, Serbia and Hungary by foot.

Why do the Syrians take such risks with their families? Quite simply because their lives are in danger in their own country, and it is not easy to get out by legal means; visas for Western European countries are given out sparingly, despite the seriousness of the situation in Syria. Another reason is that neighbouring countries have inevitably become less welcoming; there are so many refugees already in the Lebanon and Jordan that many newcomers tend to keep on travelling. And in Egypt they are actively discouraged from staying.

Analysis by non-governmental organisations who monitor the human rights of foreign nationals shows that the more the borders are closed, the more people find ways around them. And the more that walls are erected, the greater risks migrants take. The agency Frontex says there can be some perverse effects arising from EU policy on the issue. For example, the rescue operation launched by the Italians, known as Mare Nostrum, may have encouraged traffickers to overload their boats, knowing that someone would come to their aid. However, it is by no means certain that stopping this operation and replacing it with Operation Triton, operated by Frontex and which is less ambitious, less proactive and less well funded than Mare Nostrum, will change traffickers' behaviour.

In the end, the people smugglers benefited in 2014 from the absence of European solidarity, with other EU members allowing Italy to shoulder the burden for dealing with the migrants. They have also benefited from an inconsistency in the application of rules that stems from this lack of solidarity. For example, by not always taking migrants' fingerprints – as they are supposed to under EU rules – the Italians have effectively encouraged the migrants to continue their journey northwards into other EU countries, abandoning them back into the hands of the traffickers.

------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this story can be read here.

English version by Michael Streeter