More than five years have passed since France launched its military intervention in Mali to push back jihadist forces from overrunning the country, but the profound crisis into which this West African nation of around 18 million people has long been plunged, in part from the results of the civil war in Libya in 2011, remains.

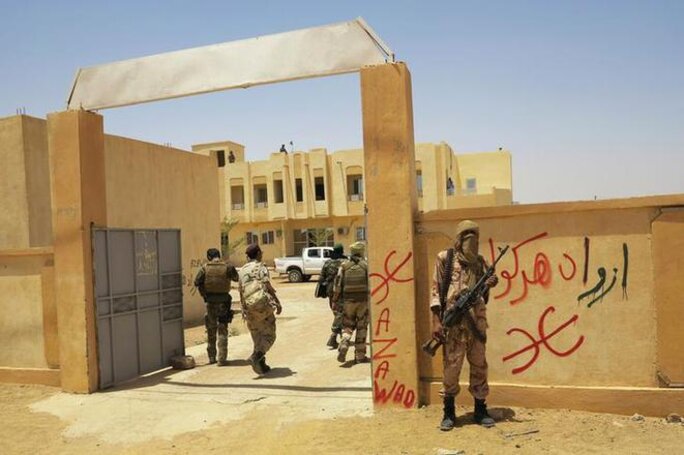

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Meanwhile, the destabilisation of Mali has made it a hub in the process of a wider destabilisation of the surrounding Sahel region.

The 2011 NATO campaign to overturn the regime of Muammar Gaddafi in Libya, an aerial bombing campaign actively led by France, with Britain in toe, and with US backing, was to have repercussions well beyond Libya’s borders. It created an enduring chaos in all the countries of the Sahel region, and not least in Mali.

“One would have had to be blind not to see the chaos that it would produce to the south of Libya, and deaf to not hear the advice of those who called for prudence,” said a French diplomat about the 2011 military intervention in Libya, a serving specialist on the Sahel region who asked in this interview with Mediapart not to be named.

In the preparations for the campaign, the then French president, Nicolas Sarkozy, had been warned by heads of state of this sub-region about the dangers that putting a swift end to the Gaddafi regime presented to the stability of their own countries.

In his book on the subsequent French military intervention in 2013 in Mali, La Guerre de la France au Mali (France's war in Mali), French journalist Jean-Christophe Notin, who specialises in intelligence issues, describes how the French military high command “very early on weighed up the consequences for the region of operation Harlattan” – the name given to the French operations in Libya.

Notin cites colonel Yves Métayer, a member of the Africa desk of the high command, who said the calculated consequences of the Franco-British toppling of Gaddafi were put to one side “because the political priority was clearly elsewhere, in Benghazi”, the eastern port city in Libya where opposition to the Gaddafi regime was launched, championed by Sarkozy’s friend, the prominent French essayist Bernard-Henri Lévy, and where, after the conclusion of the NATO campaign, Sarkozy and then British prime minister David Cameron made a triumphant visit in September 2011.

Both the French foreign ministry and the French foreign intelligence services, the DGSE, had over time built close links with representatives of the Tuaregs, a semi-nomadic Muslim people, a large number of whom had made up part of Gaddafi’s army, and the agency well realised the potentially explosive situation of their return to former homelands – notably Mali and Niger – south of Libya.

Over a period of almost 40 years, the Gaddafi regime had welcomed and protected the Tuaregs who, fleeing severe droughts in the regions they occupied in Algeria, Niger and Mali, first arrived in Libya in large numbers in the 1970s. That was when Gaddafi seized the opportunity to recruit many of the young Tuareg men into his armed forces.

The Tuareg recruits were to make up most of Gaddafi’s ‘Islamic Legion’, a paramilitary force created in 1972, also called the ‘Green Legion’, which notably fought in the civil war in Lebanon in 1981 and, in 1986, in the Chad-Libya conflict. They included El-Hadj Ag Gamou, now reconverted as a general in the Malian army, and Iyad Ag Ghaly, a former Tuareg rebel leader from Mali’s northern town of Kidal, who now leads Nusrat al-Islam (meaning, Group to support Islam and Muslims), a militant jihadist organisation created in 2017 by the merger of almost all the jihadist groups of the Sahel region. Some of those from the ranks of the Islamic Legion played a major role in the Tuareg rebellions in Niger and Mali in the 1990s and 2000s.

“Gaddafi constantly blew hot and cold with his neighbours,” said the French diplomat cited above. “On one side, he destabilised them by supporting the Tuareg demands and urging them to federate together into a political force. On the other, he played the role of mediator, attempting to renew dialogue between states and the rebellions.” Gaddafi was accused of supporting the last Tuareg rebellion in Niger in 2007 but also bought, with his notorious funding capacity, peace there in 2009. “He came with his suitcases, 35 million dollars, and the rebels disappeared,” commented Mohamed Akotey, one of the leaders of a previous Tuareg rebellion in the country in 1991.

Many Tuareg militants settled in Libya, usually after peace agreements were reached in countries where they were involved in rebellions, and returned to their homelands after operation Harmattan was launched against the Gaddafi regime. That was the case of Ibrahim Ag Bahanga, who returned to his native town of Kidal in northern Mali in the middle of 2011 where he intended to take up armed rebellion again before dying in a car accident in August 2012.

While Tuaregs served the Gaddafi regime within the ranks of the Libyan armed forces, there was also in Libya an exclusively Tuareg unit of around 3,000 men, created in 2004, called the Maghawir Brigade, led by general Ali Kana. During the 2011 civil war, it fought on the side of Gaddafi before finally abandoning the doomed dictator. There were hundreds of desertions as of August 2011, when some found refuge in the south of the country (where today, regrouped, they play a key role), while others returned to their native Mali and Niger.

The authorities in both Mali and Niger had foreseen the likely influx, but their strategies differed. In Niger, the government of President Mahamadou Issoufou opted for the carrot-and-the-stick approach, sending emissaries to Libya to inform the Tuareg fighters that they would be free to return home, and would receive help with their resettlement, but on condition that they lay down their weapons. Those who did not comply with the arrangement were met with force. “We sent the most part of our troops to border [editor’s note: with Libya] and intercepted everyone,” later explained Nigerien army colonel Mahamadou Abou Tarka, who presided over the country’s high authority for consolidation of peace (the HACP), a body set up to deal with the various threats of destabilisation in Niger. “There were several skirmishes,” he added. “It had a dissuasive effect.”

But in Mali, then-president Amadou Toumani Touré took a different approach. He sought to negotiate with the Tuaregs, and in the summer of 2011, as the Libyan civil war reached its climax, he sent General El-Hadj Ag Gamou to Tripoli and Benghazi. There, he proposed to the Tuaregs from Mali that they could return to their homeland while still armed on condition that they allied themselves to the state authorities. He successfully convinced those from his own tribe, the Imghad, who returned to Mali in October 2011 and formed a battalion of more than 300 combatants who fought alongside the Malian army when war later broke out in the north of the country. But Gamou failed to win over other Tuareg groups in Libya, notably the Ifhoga, Chamanamasse and Idnan clans. These, heavily armed, returned to Mali at the end of 2011 and at the beginning of 2012.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Their arsenal, in part made up of stocks from the former Gaddafi armed forces, included machine guns, AK-47 assault rifles, and rocket-propelled grenades. Commanded by Mohamed Ag Najim, a former member of Gaddafi’s Islamic Legion, they were intent on becoming a force top be counted with in Mali, a country that many of them, although historically their homeland, were discovering for the first time. Mohamed Ag Najim, who had in 1990 taken part in a Tuareg rebellion in northern Mali, had served as a colonel in Gaddafi’s army and after the civil war broke out in Libya in early 2011 he was for a while put in charge of ensuring the safety of part of Gaddafi’s family before he finally abandoned the dictator’s cause.

The number of Tuareg fighters who returned to Mali, variously estimated at between 1,000 and 1,500, were better organised than, and also outnumbered, those returning to Niger. They met with no opposition from the authorities, even though Malian army reinforcements were sent to the north of the country at the end of 2011. Mali’s then-president, Amadou Toumani Touré, wrongly believed he could negotiate a peaceful resettlement. In October 2011, two irredentist movements who until then had kept a low profile, the National Movement of Azawad (after the name given to northern Mali by Tuaregs) and the Tuareg Movement of Northern Mali merged to create the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad, the NMLA.

For the NMLA leadership, the return of the Tuaregs from Libya was an opportunity to mount a new offensive against the Malian authorities, and the revenants were to make up most of the NMLA’s paramilitary force. Ag Najim became the movement’s chief of staff.

Did France spirit the Tuaregs back from Libya into Mali?

In early January 2012, the government sent a former Tuareg rebel, Mohamed Ag Erlaf, to negotiate a peaceful solution with the rebels to their threat of renewed armed conflict. But in vain. A few days later, on January 17th, the MNLA fighters attacked the north-east Malian town of Menaka, and rapidly went on to overrun Kidal, Tessalit, Gao and Timbuktu. Four months later, and following a military coup which on March 22nd had toppled president Amadou Toumani Touré, the Malian army had lost control of the north of the country, and on April 6th the NMLA proclaimed the independence of Azawad.

But the Tuareg independence forces were subsequently supplanted by the armed jihadist groups which had initially leant them support. The jihadists had settled in parts of the north several years earlier when, tolerated by the Malian authorities, they had manifested no intention of extending the territory they first controlled. After taking control of key sites from the NMLA, the jihadists then began to drive south, reaching the centre of the country in a push that threatened to eventually overrun the capital Bamako further south. In face of the crisis, in January 2013, France sent more than 5,000 troops to its former colony to push back the Islamists, baptised Operation Serval. Three months later, after French forces had driven the jihadists back to the north, the United Nations sent to Mali an international peacekeeping force of 11,000 men, under the mission title of MINUSMA (United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali).

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Ever since, Mali has remained a country at war.

In August 2014, with Operation Serval wound down, France launched Operation Barkhane, based in Chad, involving around 3,000 French troops and targeting jihadist insurgents across the western Sahel region. But the jihadist groups continue to pose a significant threat in the region, while civilian casualties in Mali have been increasing (see the December 2017 UN report on its mission in Mali here).

Would all these events have unwound without the 2011 military intervention against the Gaddafi regime in Libya, driven by French president Nicolas Sarkozy? For the NMLA, the answer is that they would have. “It was inevitable,” said one of the movement’s political bureau, whose name is withheld. “The population was too angry. It would have risen up one day or another.” The passive approach of former Malian president Amadou Touré, now exiled in Senegal, along with the strategic failures of the Malian army’s commanders, are also targets of criticism from some quarters for the situation. But whatever the conflicting views, most specialists of the region agree that without the support of the Tuareg fighters returning from Libya, and without their weaponry which was on a par with that used by the Malian army, and also without their know-how in military combat, the NMLA offensive launched in early 2012 with all its consequences, would have been quashed.

Another question raised by some is whether the Tuareg fighters in Libya, who represented a significant supporting force for Muammar Gaddafi, were encouraged to return to their homelands by France in order to facilitate the fall of the dictator. “The French told them that they should abandon Gaddafi, and that if they went home, they would leave them in peace, that they would even help them take the north,” said a Malian army officer, whose name is withheld, who had served in a position close to president Touré. He said he recalled that at the time of the overthrow of the Gaddafi regime, relations were frosty between Bamako and Paris, notably on the subject of military cooperation; in August 2011, Touré had refused to allow the French to set up a communications eavesdropping base at Sévaré, in the centre of Mali.

But while that hypothesis is often heard in Bamako, there are doubters among specialists of the region. “In mid-2011, the Tuaregs had understood that the days of the Gaddafi regime were numbered and that it was best for them to play their own hand,” commented a mediator who has regular contact with Tuareg representatives, and whose name is also withheld. “They, too, had NATO bombs dropped on them, that shouldn’t be forgotten.”

What does appear a likely scenario is that rather than enjoying active support from France in establishing themselves back in northern Mali, the Tuaregs leaving Libya were allowed a certain freedom in returning with their weapons and baggage, perhaps even an assurance that they would not be targeted by NATO attacks. Mali is separated from Libya by Algeria, to the north, and Niger, to the east, through either of which returning Tuaregs would have to pass to reach northern Mali. The above-cited Malian officer recalled: “It was the beginning of January in 2012. The rebels arrived in a convoy, 20 trucks stuffed with weapons, 500 to 600 men. And no-one warned us to their arrival, neither the Nigeriens, the Algerians, nor the French. Yet Mali doesn’t have a direct border with Libya.”

At the time, special French forces, who were based in the Burkina Faso capital Ouagadougou, were given the task of watching movements across the border in southern Libya in the event that Gaddafi might have tried to flee the country. Those close to former Malian president Amadou Touré point out that such a huge Tuareg convoy cannot have escaped their surveillance.

Mohamed Ag Najim, the Tuareg former colonel in Gaddafi’s army, who later became NMLA leader, was during the same period in contact with the French external intelligence agency, the DGSE. When French troops pushing back the jihadists in Operation Serval liberated the town of Kidal in northern Mali on January 30th 2013, it was Ag Najim who welcomed them. In his book, Jean-Christophe Notin wrote that Ag Najim returned to Mali, “not only in pique […] but because he was invited to do so by different sides”, while also observing that “no doubt the DGSE used its old relations to dissuade them [the Tuaregs] from opposing NATO”. The diplomats at the French foreign affairs ministry at the time regularly complained of what they saw as the DGSE’s pro-Tuareg leaning.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.