It it 1,442 pages long, has 35 contributors, contains 500 biographical notes, and features hundreds of iconographic documents and articles about all the political and historical issues raised by the great Paris uprising that began nearly 150 years ago, on March 18th 1871.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The vast nature of this new work, called La Commune de Paris 1871. Les acteurs, l’événement, les lieux, ('The 1871 Paris Commune… The participants, the event, the locations'), recently published by L'Atelier, is certainly impressive. But it would be a shame if this book were to be regarded solely as a commemorative reference book, given the way that it explores both the reality of the uprising and the way it still resonates to this day. For as the book's coordinating editor Michel Cordillot notes, the Paris Commune of 1871 has “never stopped being the focus of new research and passionate debate”.

This event, which according to Cordillot is “incapable of creating consensus”, has been used by politicians in many different ways in the last century and a half. In particular, the story of the Paris Commune was adopted by the Popular Front or Front Populaire, the alliance of left-wing movements between the world wars in France. It then returned onto the national scene in spectacular fashion in the events of 1968 when it was held up by protestors as a vivid contrast to the “fossilized” French Communist Party. In recent years the memory of the Commune has helped feed ideas on the radical Left in the form of “libertarian questioning of democracy”, to employ a phrase used by leading Commune historian Jacques Rougerie. It has also been seen recently as a model for how to defend protest camps and has been used in the left-wing or anarchist works of the anomalous authors behind the Comité Invisible or 'Invisible Committee'.

More surprisingly, the book describes how “a section of the extreme subversive Right – from the [editor's note, nationalist] boulangistes” to extreme nationalists and French fascists – have “tried hard to appropriate the Commune”. In fact, in 1944 the French fascist leader Jacques Doriot (1898-1945) took his volunteer troops to the Paris memorial in honour of those who died in the Commune – the Communards' Wall or Mur de Fédérés – along with the notorious Charlemagne Division of the Waffen SS. Here, the book notes, they staged a “hybrid form of memorial, an unlikely and monstrous gathering”.

The events of 1871 have not just entered political culture but popular culture too, though not always in a sympathetic light. For example, in his controversial popular history book Métronome the French actor Lorant Deutsch borrowed an old reactionary view of the Commune in equating it to vandalism.

All this has helped to shroud the historical events of 1871 in myths and “delusions” about what the Commune was and what its aims were, the book notes. The paradoxical result is that, despite the thousands of bibliographical references to it, the Paris Commune remains “quite poorly understood”.

In a bid to overcome that, this new book draws heavily on the abundant historical research that has taken place since the Commune's centenary, and it has woven together three forms of writing to help understand an event whose very name lacks historical consensus; the word “commune” being something of a catch-all term.

Michel Cordillot notes in the text that the idea of communalism in fact “developed slowly after the fall of the [Second French] Empire [in 1870], coalescing around several key ideas”. These ideas were: “[T]he masses rising to defend their invaded motherland – during which the glorious precedent of Year II [editor's note, September 1793 to 1794 according to the Revolutionary Calendar of the French Revolution, a year which included the Reign of Terror and fears of a foreign invasion by the Coalition powers] was recalled – the establishment of Republican institutions able to promote authentic social and democratic measures whose nature still remain to be defined; and municipal freedoms being restored to Parisians.”

The first form of writing in this vast tome consists of biographies of around 500 key players in the uprising, continuing the work begun in the biographical dictionary of French workers movements the Dictionnaire biographique du mouvement ouvrier français, established by French historian Jean Maitron. Often just known as 'Le Maitron', this reference archive is now available online. The biographies in 'La Commune de Paris 1871' were chosen because they chart the lives of individuals for whom the Commune marked the culmination, the focal point or the start of their radical commitment and indeed in some cases their existence. They give the reader a concrete idea of the wide diversity of ideological backgrounds that ultimately led to a belief in what the Commune stood for.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The second type of writing is in the form of concise and documented summaries which pose key questions about almost all historical aspects of the event. For example, one describes the workings of the Commune's military force the National Guard, which was made up of every able-bodied man in Paris. This force had a democratic function that enabled its officers to be dismissed, which did not always lead to military efficiency.

Reading this account, one understands why the National Guard's march on Versailles to confront the French army – which was under the control of the French government based in Versailles and which was planning to recapture Paris – on April 3rd and 4th 1871 was so late and unsuccessful. Many of the major figures in the uprising were wary about increasing the risk of a civil war and wanted to give the Commune an unarguable democratic legitimacy by organising elections before pressing home the military advantage provided by the uprising on March 18th 1871.

The causes of the uprising itself, says the book, are to be found at the meeting point of three “distinct but converging” dynamics that came together at the same moment. These were the long-term trend towards Republicanism in France, the economic and political context which allowed workers' organisations to develop and also led to a rise in workers' demands and, thirdly, a patriotic aspect against the backdrop of the Franco-Prussian war. The French capital had been besieged by German troops since September 1870.

Theses summaries also analyse the Commune's “moral” aspect. It shows how an anti-Commune bias from the 1870s onwards led to the development of a moral or rather immoral view of the Commune. It was not seen as a political or social project but rather as a fundamentally immoral insurgency against a background of general disorder.

This viewpoint overlooked the fact that the 'communards' themselves constantly highlighted the “moral break characterised by a new world founded on political and social revolution” and the need for a “citizen morality”, which stigmatised “thieves” and encouraged virtuous behaviour, even if its morality was “not exactly that of the opposing side”.

Elsewhere the book describes the “opposition” to the Commune within Paris itself. In fact, though there was a struggle between 'Paris' on the one hand and 'Versailles' on the other, and though it enjoyed undeniable popular support, at no time was backing for the Commune “unanimous among the people of Paris” and its actions were indeed “hampered by fairly strong opposition”. These included groups known as the “Amis de l'Ordre”, those who had fled Paris to escape the Prussian siege and various conspirators and saboteurs.

The end of the Commune was, moreover, greeted with several demonstrations by people happy to see its demise. There were also some 400,000 acts of denunciation of individuals, often anonymous, after the Commune capitulated.

Was the Commune a 'socialist revolution'?

The book also tells us more about the role of women in the Commune and their questioning of the existing social model. This approach was not to the liking of most of the male workers' leaders, many of whom were, in this regard, close to the notoriously sexist views of the French anarchist and philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon (1809-1865).

No women took part in the Commune's government which took little interest in their demands, even if some women's committees were set up and a number of women took part, on the barricades or elsewhere, in the fight against the Versailles forces. There was even a women's battalion, called the Légion des Fédérées, which was set up in the 12th arrondissement or district of Paris.

The Commune's opponents in Versailles developed a particularly negative view of people whom they saw as having broken with the norms of social behaviour. This was summed up in the image of the so-called “female fire-raisers” or “pétroleuses”, women who were supposedly roaming the streets of Paris and destroying buildings using milk cans filled with petrol. These acts apparently “symbolised the complete violation of feminine identity”, the nurturing mother who had become a criminal firebrand. Yet as the French writer Maxime Du Camp, who was on the Versailles side, himself ultimately recognised, these “pétroleuses” were “fanciful beings, comparable to salamanders and elves. The councils of war did not manage to produce a single one.”

Yet even though this image of female firebrands showed itself to be completely fictional, it has remained one of the key clichés about the Paris uprising. As recently as the spring of 2018, when there was an occupation of the Centre Pierre-Mendès-France, part of Sorbonne University, in Rue de Tolbiac in Paris, a banner at the entrance of the self-proclaimed “Tolbiac Commune” declared: “If the cops come in … the pétroleuses!”

Another aspect studied in the book is the Committee of Public Safety, an authoritian body set up in by members of the Commune in April 1871. The authors consider that “far from saving the communalist revolution by handing it over to the dictatorship of a few, the replacement of a messy but democratic organ of government by a centralised organisation in fact went on to prove a tragic error by breaking the unity of the communards. Worse, by denying the very idea of direct democracy, this 'revolutionary parody' contributed to spoiling an unprecedented social experiment.”

The book notes that the events of the Commune took place at a “pivotal period” when photography was in the process of replacing engravings and lithography as the medium for disseminating images. This led, among other things, to the creation of many photomontages that sought to illustrate the Commune's “crimes”. Many of these were created by Ernest Eugène Appert, a portrait photographer whose altered images were to contribute to the discrediting of the communards in the eyes of public opinion for posterity, in particular through photos of emblematic Paris buildings on fire.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Yet the book points out that notwithstanding these emblematic images of the Palais des Tuileries or the Hôtel de Ville ravaged by flames, it was in fact the Versailles side that was behind the destruction of many buildings, and that this approach was “driven by a modern if not innovative concept of urban warfare”.

Researcher Éric Fourbier notes that the “order was given to never attack the barricades directly but to encircle them either by going around them through adjacent streets or by 'advancing' through buildings; in other words, by breaking through the outer and interior walls” to establish vantage points from which to shoot.

This approach has echoes in the modern day. Eyal Weizman, the founder of the Forensic Architecture collective, noted the controlled destruction strategy of the Israeli Army in the Jenin Palestinian refugee camp in 2002 in his work 'Walking Through Walls - Frontier Architectures'.

There are thus few aspects of the Commune that this lengthy book does not explore, even though the decision was made only to focus on Paris itself. This is despite the fact that much of the new historical research on the Commune in recent years has been on the impact it had on other cities and towns in both France and abroad. The authors acknowledge that this omission is “open to question”.

Apart from a few “communalist movements in the provinces”, in particular in Lyon in the east and Marseille on the Mediterranean coast, the regions of France were mostly hostile to the insurgents' demands in Paris. Though this did not lead to them joining the ranks of the Versailles camp either, as the “lack of success in raising volunteers shows”, the book notes.

In addition to these historical summaries based on the latest research, there is also the most original part of the book, which represents its third writing format. These are the sections devoted to the many “debates and controversies” that continue to shape the interpretation of the events of 1871.

These debates concern the respective influence of figures such as Proudhon, Karl Marx, Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin and French historian and politician Louis Blanc on the Commune, as well as the relationship that it had with “direct democracy” or the question as to whether the Commune was a “socialist revolution”.

This last question immediately gives rise to others, such as the role of the First International – an organisation which sought to unite various left-wing, anarchist and trade union groups around the world – in the Commune. For a long time it was assumed to have been of decisive importance to the emergence and character of the Paris uprising. This role was highlighted just as much by the opposing forces in Versailles, who wanted to “fuel the idea of a socialist and cosmopolitan plot” against civilisation, as it was subsequently by Marxist intellectuals who were “anxious to detect in the Paris event the early signs of a revolution that was, for the first time, organised by a workers' organisation”.

In reality, its members played “no organising role in the event of March 18th, which was a popular and spontaneous movement”, even if members of the First International or International Workingmen's Association (IWA), as it was formally called, were later involved in some of the committees in Paris and even though after the Commune was crushed the IWA network ensured that many of the communards were looked after in exile.

This controversy forms part of a long-running debate over how to categorise the Paris event. Did the Commune mark the last hurrah of the nineteenth century revolutions which had been sparked by the French Revolution, or did it represent the dawn of the modern workers' movement?

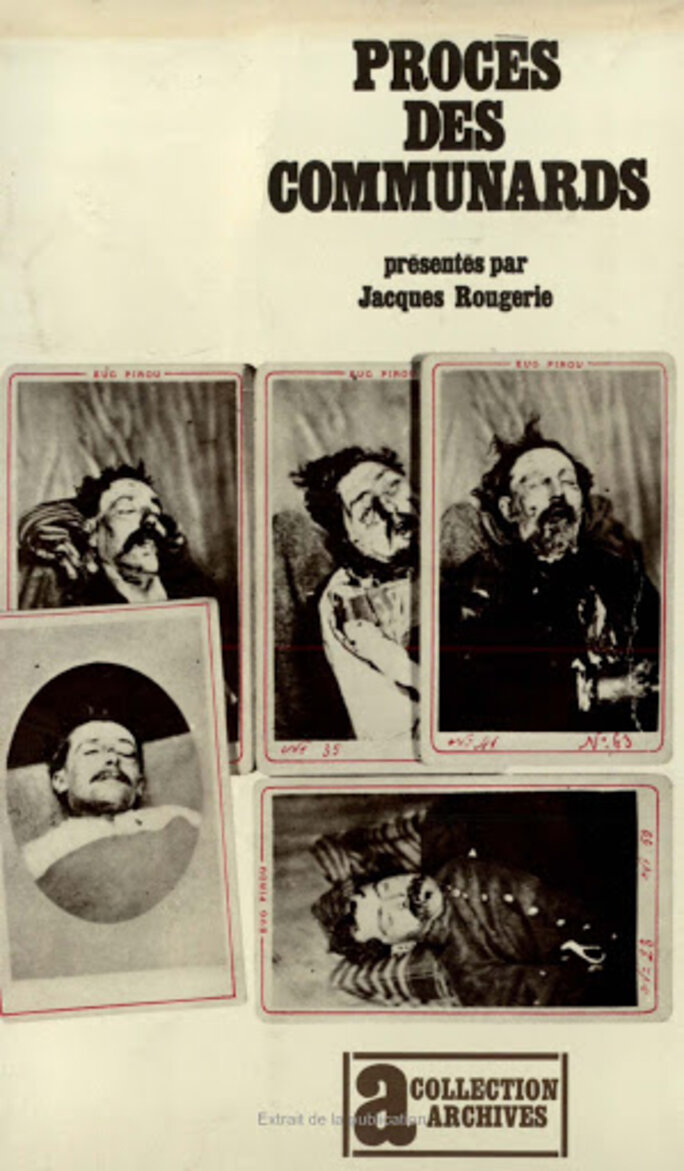

In his 1964 work Procès des communards (see right) the historian and Commune specialist Jacques Rougerie opted for the 'last hurrah' view, going against much Marxist historical writing. The authors of the new collective work also take the view that the event was less about “class struggle” than a crystallisation of “social conflicts” and was more than anything Republican and socialist in nature, but socialist in the nineteenth century meaning of the word rather than that of the twentieth century.

The relationship between the Republic and the Commune is one of the other fundamental issues covered in the section devoted to the historical controversies the event has provoked. For example, how can one explain this paradox: “The Commune was Republican and yet the majority of Republicans condemned the insurrection.”

Aside from the fact that Republicans were a diverse group, a majority of whom thought that the Commune was against the law and led to disorder, many Republicans worked to reconcile the Commune with the National Assembly, which had taken refuge at Versailles. Yet a not insignificant number of Republicans feared that the Commune “could favour the restoration of the Monarchy at a time when the Republic was weak”. The uprising occurred at a time when the Prussians still occupied France following the defeat of Napoleon III the year before and the end of the Second Empire.

The core of the debate is whether it is possible to state, as supporters of the Commune both at the time and subsequently have claimed, that it saved the Republic because the sacrifices made by the insurgents in Paris made a return to the monarchist past impossible. It is a long-running debate, and one on which the book says there is “no consensus”. Some take the view that even though the royalists formed a majority in the National Assembly elections in February 1871, they were too divided among themselves to have succeeded in restoring the monarchy.

The authors of this book consider that in reality the Commune marked a moment of “political and psychological” sea-change towards acceptance of a Republican regime in France. However, debate will long continue over the extent to which the Republic was saved by the sacrifice of communards who were, to use the well-known words of Karl Marx, “storming heaven”.

'A turning point'

This book does not just dwell on the big controversies about how to interpret the importance of the Commune. It also examines particular issues on both a micro and macro level. This allows for a close look at subjects that might at first glance seem technical, such as the attitude of the Commune towards the Bank of France. The accepted wisdom among activists is that the refusal by the Commune to take control of the resources of the Bank of France was a “major error, a blunder even” committed by people whose approach was “far too moderate”.

This view was fuelled by Karl Marx's reflections on the Commune ten years later. Though it does not feature in his work 'The Civil War in France' (see right) which was written at the time of the events.

The authors of 'The Paris Commune' note that the Commune showed “quite considerable respect for private property and for everything that did not directly come under the jurisdiction of the municipal government”. This stemmed in particular from the idea that there needed to be a separation between local and national issues. In April 1871 very few communards opposed a policy which “corresponded to the ideas of a large section of the Parisian workers' movement, who were careful to defend credit and not to exceed the communalist prerogatives that they had appropriated for themselves”.

Another example of the book's analytical style is seen the detailed assessment of the elections held on March 26th and April 16th 1871 and what these votes tell us about the Commune's “legitimacy”. It was in fact the initial talks between the National Guard's central committee and the mayors and Members of Parliament for Paris that led to the holding of elections to appoint the representatives of the city's inhabitants.

On March 26th 1871 a total of 230,000 votes cast out of 475,000 people on the voting register gave indisputable authority to communalist candidates against the existing order. The election also showed a marked difference between working class districts and more middle class areas. The relatively high abstention level could be explained by the departure of many residents from the capital, with many men fearing that all adults would be forced to serve in the National Guard's fighting units.

The additional elections held on April 16th, however, showed that there was real disaffection among voters by then, with an abstention rate of close to 70%. To this day that figure is used by some to show the Commune's lack of legitimacy. But the authors point out that there were legitimacy issues on the other side too. The National Assembly was elected in February of that year when a large part of the north east of the country was under Prussian occupation and that no election campaign took place.

But without doubt the historical controversy that provokes the greatest political differences is the issue of how many died in 'La Semaine sanglante', or 'bloody week' that ensued when the Versailles authorities' army entered Paris on May 21st and ended the Commune. Some historians and political activists estimate the death toll at more than 40,000 while in 2012, in an article called 'How bloody was La Semaine sanglante of 1871? A revision', the British historian Robert Tombs argued for a much lower figure of between 5,700 to 7,400.

The historian Quentin Deluermoz, who trawls back over the debates, does not believe this battle of the figures is a pointless exercise. In the history of the French Revolution, for example, recent work has shown that some events have been afforded too much importance in relation to others which suffered just as high a death toll. An example is the rarely-mentioned battle at Montréjeau near Toulouse in south-west France in 1799 where close to 5,000 people died.

In the case of the Commune, the dispute over figures is important because of the underlying interpretations involved. Robert Tombs, who is interested in the forgotten side of this story, the Versailles camp and the soldiers of 'La Semaine sanglante', does not consider this revised figure in any way undermines the fact that the week was a “terrible atrocity, surely the worst single episode of civil violence in Western Europe during the nineteenth century ”.

But it does allow him to state that “May 1871 is not the apogee of violence in French history. It was not a quasi-racial extermination, not an indiscriminate massacre of proletarians by peasant soldiers obeying bourgeois masters...” There is a risk, though, that this approach can normalise a massacre that was exceptional in nature and one which constitutes a grim milestone in the annals of state violence.

What remains striking today is how such a brief episode continues to spark so much debate and scholarship. The Commune began life on March 18th 1871 and was fully established by March 29th; its meetings came to an end on May 21st. This means it was fully in existence for just 54 days. In such circumstances, and at a time when they were waging a war, were the communards able to change lives in a lasting way? “Without doubt, no. But, however, they did more and did better than the governments that had preceded them,” states coordinating editor Michel Cordillot.

This can be seen in social and employment issues. There was a moratorium on rents and debts in the Commune, and a ban on selling goods pawned at pawnshops, while a person who had acquired loans of less than 20 francs from a pawnbroker was later permitted to get their goods back free. Vacant buildings were requisitioned, night-time working in bakeries was banned, and workers' associations were given the chance to take over the running of abandoned workshops. There was also a ban on employers deducting money from wages as fines or punishments.

But there were also changes of a political nature. The state of siege was lifted, restrictive measures on the popular press were abolished and there was a formal separation of church and state. On a more societal level, schools were made secular, there was pay equality between male and female teachers, partnerships or 'free union' between men and women were recognised, and there was also equality of rights between all children - legitimate or illegitimate - of members of the National Guard who died in combat.

In any event, the Commune was a “turning point, both in the move towards the Republicanisation of France in the long term and in the realisation that the idea of representatives of the working classes coming to power was no longer in the realms of the unthinkable, thus opening the way to the social and political struggles to come”, notes the book. This explains why the Commune continues to fuel and divide the memories which have taken hold of it.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter