The end of summer marks the start of the new literary season or 'rentrée littéraire' in France. And one emerging theme of the books coming out this autumn is that of France's recent industrial and social conflicts. These include the long-running 'gilets jaunes' or 'yellow vests' protests against the government, the demonstrations and strikes against pension reforms and the trial and conviction of senior executives at France Télécom over “moral harassment” that led to a spate of suicides at the telecommunications giant.

It takes time to come up with a narrative, work out the theme and find the right words to convey them. So there is always a risk that a book will be out of date by the time it appears, after the event. Moreover, events in the modern world no longer languish unvarnished and raw, but are instantly given an angle, their own gloss, as they immediately get caught up in rolling news and endless discussion. So why would we want to look back on social movements that now seem so distant, taking place as they did before the black hole of lockdown?

One reason of course is that the past matters, and that this past will surely return one day in the future. But what is at stake is not just taking stock and marking an important moment; more than anything it is about taking a different stance, developing your own narrative which enables you to switch direction and to adopt a divergent view.

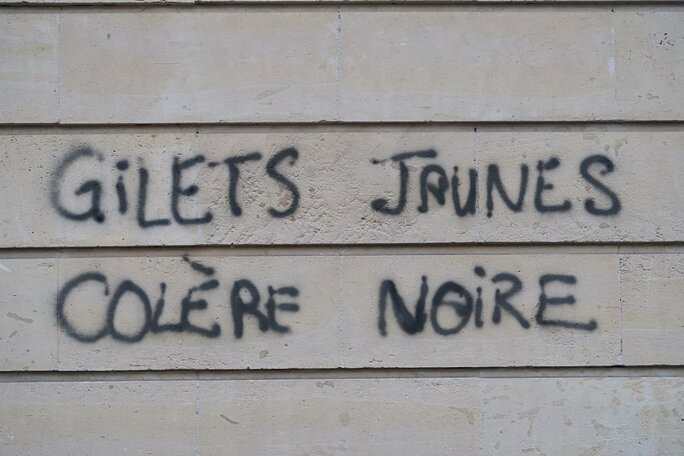

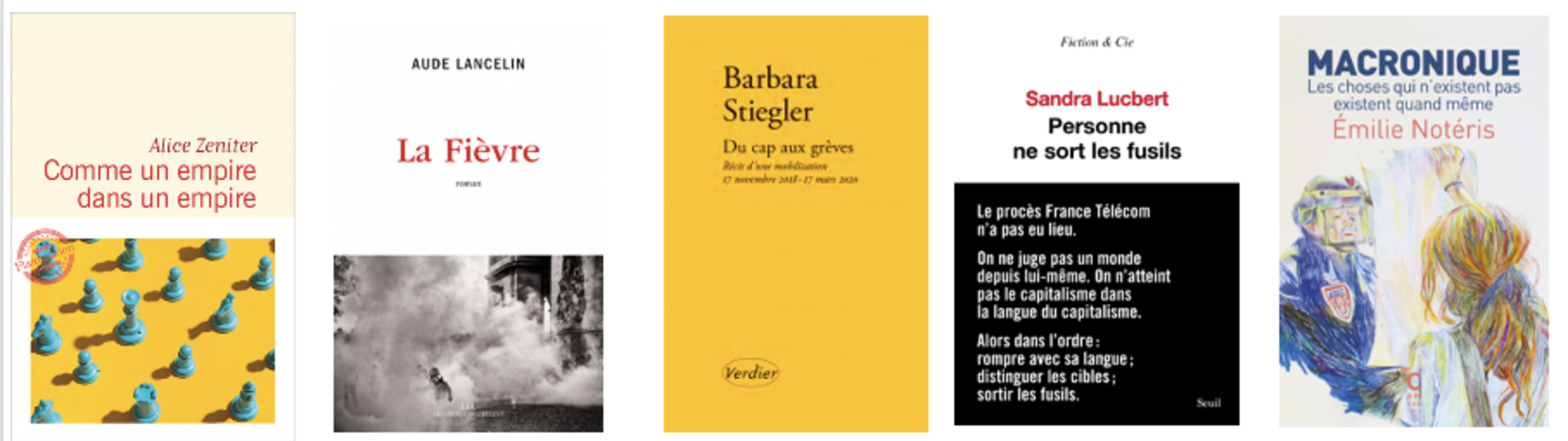

Enlargement : Illustration 1

That is what Sandra Lucbert explains at the start of her fine book devoted to the France Télecom trial, Personne ne sort les fusils ('No one got out the guns'). The author, like other researchers and writers (including French scriptwriter Alain Damasio), followed the 2019 trial (see what was written at the time here). She captures both its tragedy and its scandalous nature. The book, which sets itself the task of “describing a killing”, consists of a series of short, incisive chapters which strip away the corporate paraphernalia which skirts around - or even justifies - the suicides, all in the name of putting profits first.

Lucbert immediately starts with a confirmation of Godwin's law (about how so many discussions ultimately end with a comparison relating to Hitler or the Nazis) as she notes that when the Nazis were tried at Nuremberg after World War II, the Allied system of trial was different in nature to the defendants' system. Whereas the author notes that in the France Télécom trial the court spoke the same language as those of the accused: that of our neoliberal world. In such circumstances how does one manage to capture the horror of the proceedings?

The author explains how: she has the tools to do this because she speaks languages that are different from those of the accused. “I carry around with me a number of language types, that's what literature does to those who practice it. It imposes a permanent distance in all that you say. I speak the collective language, but this is set against an internal cacophony.”

Thanks to this distance and the external vantage point it gives, it became possible to observe the logic of the arguments and the speeches in the trial, and to extract that logic from them. “The France Télécom trial is the story of an embedded grammatical position,” she writes, because, it turns out, it is all about grammar; the grammar of the narrative, the grammar of the language. In other words, it is about the logical setting out of an action and of actions, of causes and consequences, of both major and minor positions. In summary, it is a place where hierarchies, the machinery of power and systems of thought are produced.

Other books this autumn share this same conviction; that literature can be a tool to free yourself from the logic of dominant ideas, to gather your strength and then return to the fray.

What is most striking is the anger involved. Alice Zeniter's previous novel, L’Art de perdre ('The art of losing') published in 2017 and which won the Prix Goncourt des Lycéens literary prize, was a melancholic quest to discover the origins and ravages of history. Her latest novel, Comme un empire dans un empire ('Like an empire within an empire'), is written in the present day and concerns young people who want to take back control of their destiny. It contrasts the lives of the two protagonists, each representing two different ways of acting. One is a hacker, the other a Parliamentary assistant. One is outside the system, one is inside, one attacks institutions head on, the other works with them. Both have experienced social humiliation, and the book forges a powerful dynamic narrative out of this.

In one of its best passages the novel produces a stinging comparison between “talent shows” - such as 'American Idol or 'The X Factor' – and the public displays adopted by company bosses when they are making people redundant. It is a way of highlighting the violence that exists in these media events. “The candidates had to use songs to beg rich and famous individuals to give them the chance to come back the following week (to beg again), and these same rich and famous individuals sighed how what they were being asked to do (to choose and eliminate) was all too hard, really too hard”, like the “millionaire boss” who had just “stated on television that closing the factory was really too hard for him, really hard, so unpleasant....In front of him workers were humiliating themselves in order to be able to work a few more months,” writes Zeniter.

Observing and contemplating the enemy in order to get into their heads; the books out this autumn certainly make personal commitment something of a requirement. This means getting out and about, changing your daily routines, and also getting personally involved and resorting to action. That is what the Parliamentary assistant Antoine experiences when he goes in search of the 'yellow vest' protesters in his Member of Parliament's constituency. He has to go looking for them at edge-of-town roundabouts, but when he does find them he realises he is utterly at a loss. “Once there, Antoine feels idiotic because it was difficult to look at a barricade. You either take part in it or you move on.”

But what does getting involved mean? What consequences will it have on our lives? Those are the issues at stake in La Fièvre ('The Fever') by Aude Lancelin, a former assistant editor at L'Obs and Marianne magazines who founded the web channel QG after resigning as the head of news site Le Média. In 2016 she was awarded the Renaudot prize for her essay Le Monde libre. La Fièvre is her debut novel and is visibly inspired by real events. In it she imagines that a Parisian journalist goes off to encounter the 'yellow vests' at Guéret in central France, and there follows the case of a young unemployed electrician, Yoann, who had been convicted for throwing a paving slab at a protest on the Champs-Élysées in Paris.

In Yoann's case the protests trigger a tragic series of events; while for the journalist, and one assumes the author as well, it is a painful initiation into the realities of modern class struggle. It is a coming-of-age novel, but 21st century-style; while the journalist learns about the need to take action the outcome, far from being happy or one of reconciliation, is in fact discouraging. “The apartheid between our lives is real,” it concludes.

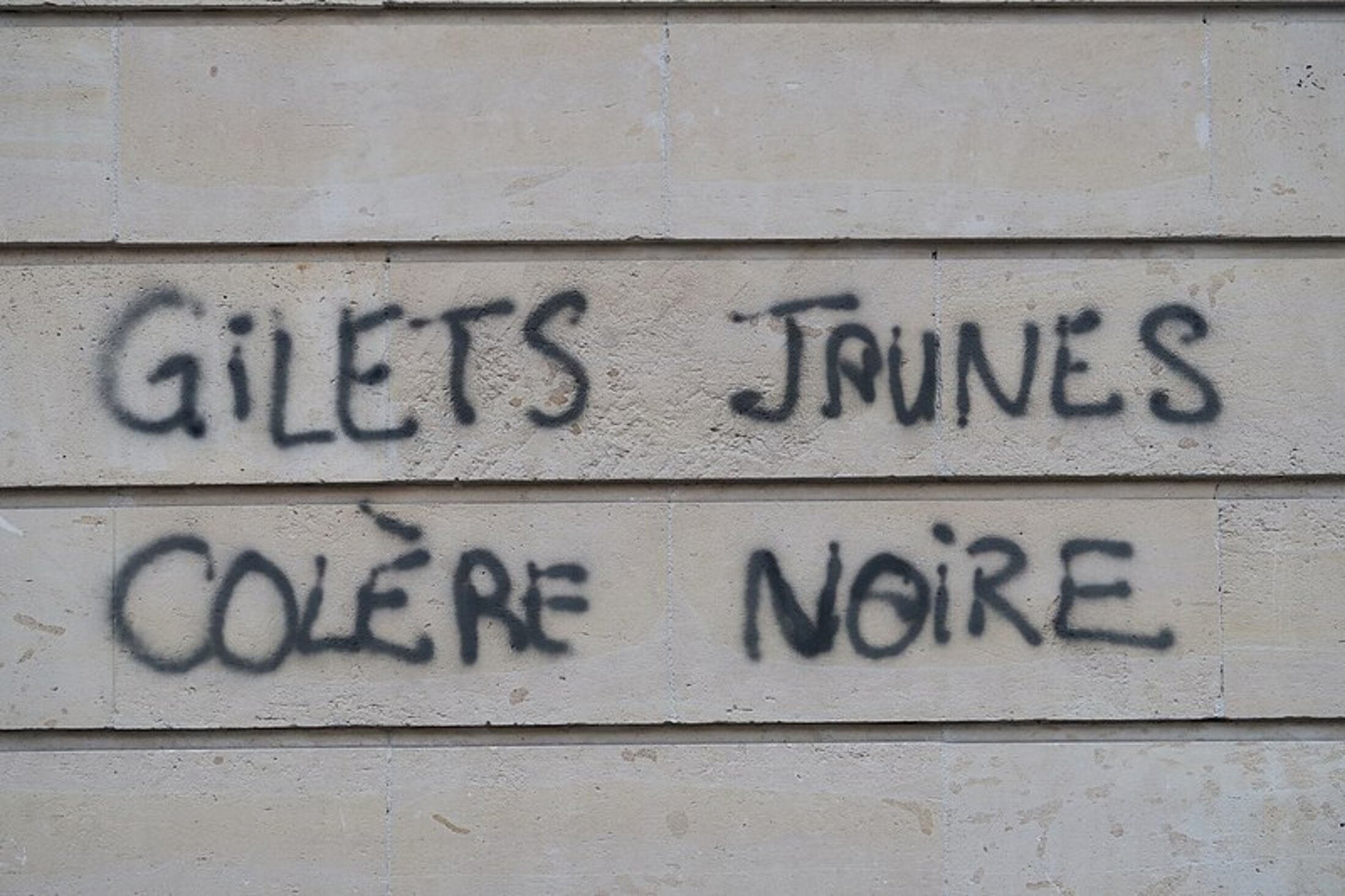

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Yet this is no time to be downcast: reading Barbara Stiegler's Du cap aux grèves. Récit d’une mobilisation, gives one renewed vigour. At the end of 2019 the philosopher published an essay Il faut s’adapter. Sur un nouvel impératif politique, ('The need to adapt. On a new political imperative') which shows how neo-liberalism has developed a notion of 'educating'. Faced with a recalcitrant population, which is unable to adapt to the new environment of global trade, this education involves benevolently – and with authority - imposing the new aims of this economy, which boil down to widespread competition.

To the author's own surprise her latest book, originally conceived as an archaeological-style delve into the dominant streams of modern thought, ended up being very topical because of the social movements swirling around at the time of its publication. In Du cap aux grèves Stiegler describes, in the manner of a diary or a personal essay, what she has gone through in recent months, from the start of the yellow vest movement to the eve of the coronavirus lockdown.

Hers is a modest project, the text is necessarily very self-centred; and the result is great. It is a book with no baggage, which is simply happy to tell the story of a personal tipping point, which is no small achievement in itself. It describes how a philosopher who thought she had to keep her distance, in order to be able to reflect, then finds herself caught up in the movement and tries to create the right conditions for “practical-critical” activity - to use the words of Marx in his Theses On Feuerbach - which establishes the “reality and power of thought, the proof that it is of this world”.

This journey does not of course take place without misguided acts, disappointments and much questioning. But the process helps identify a key point: that you start by fighting where you are, with the means that you have, without looking further afield and aiming for distant targets, a mass revolution. This is because “in the great game of the masses and massification, it is always capitalism that wins in the end”.

This is a story in the first person which is without affectation; because speaking in one's name is the only way to show that “what's at stake is indeed ourself and our own private transformation in our relationship to work, to education and health, in our private relationship with space and time”.

Barbara Stiegler's decision to write this short book in a mixed format is a political statement but it also makes a literary point, highlighting the dividing line between the various books published this autumn that take the recent protest movements as their theme.

Some use the old novel form, such as the books by Alice Zeniter and Aude Lancelin, others work with a mixture of forms, somewhere between prose and poetry, essay and narration. And it is striking that it is the novels which fail to convey the anger, whereas it is Barbara Stiegler and Sandra Lucbert, with their strange hybrid formats, who take the reader with them. It is worth having a closer look at this difference. There are three reasons for it, which come down to writing and political choices; in short, to questions of literary grammar.

There are of course some particular reasons for the difference. Aude Lancelin's La Fièvre quickly becomes a roman à clef ; each character is just the fictional mask of a real person, that the reader can identify from just a few sparse clues. This is particularly true in relation to some leading figures in French intellectual life; there is no problem in identifying a philosopher and economist from the far left, for example, or an historian from the prestigious research establishment the Collège de France. One result is that the polemical power of the text gets lost in individual condemnations. And in the end the book delivers a rather poor and sad notion of what literature can achieve, using it just as code for real life.

Novels today are often just about that, pretending to tell a story. We are all waiting one day to read a Les Misérables for the 21st century, fiction that gives us at the same time emotional intelligence, power struggles and the energy to fight. Yet we also know that such a book could not emerge in the form of a 19th century-style epic saga, as that is no longer the format for our age.

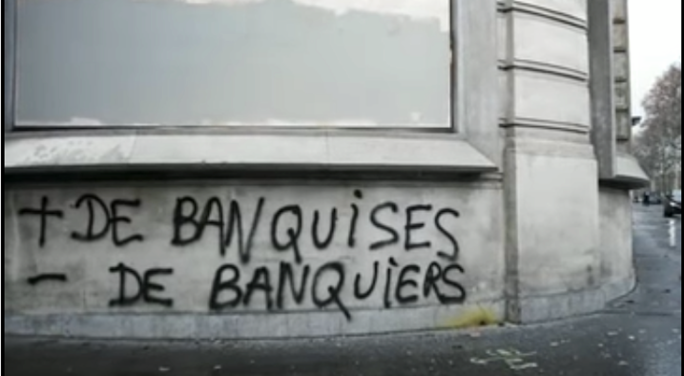

Enlargement : Illustration 3

There is also a formal and structural difference between the various books that describe political commitment. This is less about the choice of fiction on the one hand or investigative or 'reality literature' on the other. It is more than in the novels there is a need to construct a narrator and characters, while the other books are in the first person, which immediately identifies it with the author.

Using the first person to have an impact does not necessarily mean speaking with one's own subjectivity, but means speaking from where that person is, their standpoint. Nothing then stops the author becoming a ventriloquist for the enemy. That is what writer and essayist Émilie Notéris does in a small and quirky book, Macronique, the key to which lies in its subtitle: Les choses qui n’existent pas existent quand même ('Things that don't exist do exist anyway'). It employs a series of short paragraphs, sometimes in Tweet format, which are used to highlight the 'newspeak' employed in the world of Emmanuel Macron, a language which consists of saying exactly the opposite of what in fact occurs, as in George Orwell's 1984. To take an example: “There is no police violence, police violence is legal, so you can't talk about violence.”

There is no doubt that words can kill and the language that you use is directly connected to the battles that you fight. In Personne ne sort les fusils, Sandra Lucbert shows this with both anger and humour. “I discovered that the magazine I was using to swat flies was a management periodical: the Harvard Business Review France. It has glossy paper, it hits cleanly.”

Literature is also about hitting a target. Yet, paradoxically, this is what the novels here do not do, bogged down as they are in their dialectical movement and ruined by endings that tie everything up. In Comme un empire dans un empire, Alice Zeniter use narrative tension to drive the story: will the hacker and the Parliamentary assistant manage to unite and work together? But because there is no political solution to the dilemma that the novel outlines (choosing the policy of institutions or of hacking) it offers an escape route: another place, a small community where people live reconciled. So while the narrative seemed to be preparing for an explosive meeting between the two main characters, in the end it is a damp squib.

By contrast, the books by Stiegler, Lucbert and Notéris abandon the shores of standardised literary formats and their new approach manages to rekindle a notion of commitment within the words. These books are not about endings but about beginnings; they portray themselves as preludes to action, setting out the tension about what is to come, a ramping up of the language, of thought. Let us remember the drill: “So, in this order: finish with their way of talking; select the targets; get out the rifles.” These books are not about bringing things to a close; they are seeking to lay the ground for something.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Aude Lancelin, La Fièvre, published by Les liens qui libèrent, 304 pp, €20

Sandra Lucbert, Personne ne sort les fusils, published by Éditions du Seuil, 156 pp, €15

Émilie Notéris, Macronique. Les choses qui n’existent pas existent quand même, published by Cambourakis, 112 pp €10

Barbara Stiegler, Du cap aux grèves. Récit d’une mobilisation. 17 novembre 2018-17 mars 2020, published by Verdier, 144 pp €7

Alice Zeniter, Comme un empire dans un empire, published by Flammarion, 400 pp, €21

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter