It was just over a week ago and already it seems like an eternity. On the evening of December 31st, President Emmanuel Macron, speaking from the Élysée, appeared to understand the anger which had erupted in 2018. An anger, he said in his traditional New Year's Eve presidential message to the nation, which “came from afar”, an anger which “whatever its abuses and its excesses” expressed the desire to “build a better future”.

Four days later, on January 4th 2019, during a report on how the first cabinet meeting of ministers of the new year went, there was an abrupt change of direction; a million miles from this understanding approach, the official government spokesperson Benjamin Griveaux criticised the 'Yellow Vest' movement as one of “agitators who want insurrection and, fundamentally, to overthrow the government”.

The decision had thus been taken even before the next yellow vest protest planned for the following day, January 5th. Using the pretext of violent acts which did not involve the majority of people, and which moreover were solely ascribed to the demonstrators, and haughtily ignoring what was clearly the resumption of the yellow vest movement, the prime minster Édouard Philippe announced on TF1 television news on Monday January 7th a new range of repressive measures. These are intended to extend the civil responsibility of rioters, provide penalties against demonstrations that are not declared in advance, treat wearing a hood as an offence and, finally, provide powers to stop demonstrations and carry out preventative arrests of demonstrators who have got a previous record, as is done with football hooligans.

Though Édouard Philippe was not asked about police violence – even though TF1 ran an item about it on their news bulletin – it should be noted that the prime minister himself did not utter a single word mentioning or condemning it, and was happier to talk to about the 5,600 people put in custody and the 1,000 summary convictions of yellow vest protestors – figures that show the unprecedented scale of a clampdown which is causing problems for the judicial system.

As reprehensible as they may be, the violence of the yellow vests is a response to the violence of a government that does not want to listen to anything. Explicitly targeting those who “challenge the institutions”, the prime minister provided the answer as to what lies behind this stubbornness: what alarms this presidency is the fact that the political issue that is the motive behind this movement – over and above the initial causes of the cost of living and unfair taxation – directly challenges it.

That issue is the worn out nature of the presidential system, this personal government which has seized hold of the Republic, numbed and paralysed it, this elective monarchy which, through an abuse of power, ends up discrediting French democracy in the eyes of the sovereign people.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The insightful views of Mounir Mahjoubi, the junior minister in charge of digital issues and, as such, someone aware of the democratic hopes that spring from the current technological revolution, who spoke about the yellow vest protest as an “opportunity for France”, were thus just so many empty words.

“The yellow vest movement,” the junior minister wrote in Le Monde on January 1st, “are the proof that today it's possible to organise spontaneously with no intermediary. I'm convinced that it can represent an opportunity for France … What the yellow vests highlight is the urgent necessity for greater social and tax fairness as well as the compelling need to participate more actively in the working of our democracy … The immense majority of yellow vests whom I have met or who take part in debates on social media are not violent, seditious, anti-environment, racist, anti-Semitic or homophobes.”

Unpopular and powerless, destabilised by an unprecedented social movement, hemmed in by the ongoing saga of the Benalla affair involving the president's former security aide, politically disoriented, seized up administratively and deserted by a number of those closest to the head of state, this presidency is now running in all directions like a headless chicken. But as the prime minister's television intervention on January 7th confirms, all the signs are that it is not running in the right direction.

Far from adopting a noble democratic stance of worrying about both the peace of the Republic and the freedoms of its citizens, the government has made the deliberate choice to demonise the social movement that is taking place, caricaturing it as a faction of the extreme right, and to fully embrace its repressive policing, whose excesses are never criticised. In short, the choice of confrontation. Of an increased repression that leads to radicalisation.

This is what its attitude on the issue of violence indicates. Any historian of social movements could helpfully remind these rulers, who are so swift to get worked up themselves by the violence of the yellow vests alone, that violence on the streets is an echo of state violence, that brutal defence of a public, social and economic order which those who benefit from it have decreed to be unchangeable.

From the French Revolution in 1789 to the events and protests of May 1968, via the July Revolution of 1830, and the events of February and June 1848, the strikes of 1936 or the insurrections of the Liberation in 1945, our Republics, our freedoms, our rights and our institutions have always been affirmed, won in the end or progressively extended by these tumultuous revolts whose abuses, boldness and excesses have enabled new democratic and social horizons to be invented.

There will be objections, by the invocation of great figures such as Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King or by pointing to the calm determination of recent marches organised in the name of yellow vest women, that peaceful changes are preferable, given that blind violence can lead to a downward spiral that destroys the very ideas that drive it.

But this prudence does not exclude being clear-headed over the disproportionate nature of the power struggle between a state and those who oppose it, nor in particular does it exclude lucidity about this social arrogance, the expression of yet another panic by those in power, who want to see and criticise only one form of violence, that which is committed by those from below, by the people, the crowd, the plebs – whoever they are, however they come across.

A Brazilian Catholic priest and committed pacifist, Hélder Câmara, the author of an essay at the start of the 1970s called Spiral of Violence, knew just how to sum up this conformist thinking aimed at immobilising the present and shutting the door on the future.

There were, he wrote, three sorts of violence. The first was institutional or structural violence. “Now the egoism of some privileged groups drives countless human beings into this sub-human condition, where they suffer restrictions, humiliations, injustices; without prospects, without hope, their condition is that of slaves. This established violence, this violence No. 1, attracts violence No. 2,” he wrote. This second violence was that of revolt or rebellion. “...either of the oppressed themselves or of youth, firmly resolved to battle for a more just and human world.” The third is that of repression. “When conflict comes out into the streets, when violence No. 2 tries to resist violence No. 1, the authorities consider themselves obliged to preserve or re-establish public order, even if this means using force; this is violence No. 3,” Câmara wrote.

Faced with opposition in the streets, every government tends to insist that the only legitimate violence is that used by the state and its police forces. But this claim of a state monopoly on violence is only defensible on condition that it is accompanied by a strict defence of the rule of law, that is to say of individual and collective rights, in particular the freedom of expression and the right to demonstrate, enforceable by the citizens against the state that scorns them, tramples over them or represses them. From this point of view this government's public stance is completely unbalanced, adopting an unprecedented radicalisation of maintaining law and order without, ever, accompanying that with a single word to condemn excesses, without a single order to restrain them, without a single measure to curb them.

Ignoring the provocative comments by Benjamin Griveaux about the yellow vests that turned him into one of their targets, President Emmanuel Macron immediately showed how upset he was by the violent intrusion which obliged the official spokesperson to hurry out of his ministerial offices on Saturday January 5th, even though the incident caused just fear and some material damage.

On the other hand the president said nothing, his minister for the interior Christophe Castaner even less and his prime minister nothing either about the astonishing list of those seriously injured on the demonstrators' side, injuries caused by serious breaches of the code of conduct that governs the maintenance of law and order. Journalist David Sufresne has carried out an exhaustive analysis of this on Twitter.

In addition they have said nothing about the dozens of secondary school pupils humiliated at Mantes-la-Jolie west of Paris by being forced to remain on their knees with their arms on their heads for several hours last December, something which is practised under authoritarian regimes. Nor have they said anything about the police commander from Toulon on the Mediterranean coast, recently awarded the Legion of Honour, who twice hit defenceless people who were already at his mercy, and who violated all police codes of conduct, not to mention the law itself.

The fact that the state prosecutor in Toulon was able to support such behaviour – fortunately he was contradicted by the local prefect who has opened an investigation – says a great deal about the consequences inside the machinery of state as a result of this government laxness, which is spreading a repressive culture with no checks and brakes.

Once again we see that the promised new world goes along with the same old way of doing things that the president wanted to sweep away, if one recalls the tolerance of the previous presidency under François Hollande towards police violence, the death of environmentalist Rémi Fraisse and the repression of union demonstrations against the El Khomri employment law.

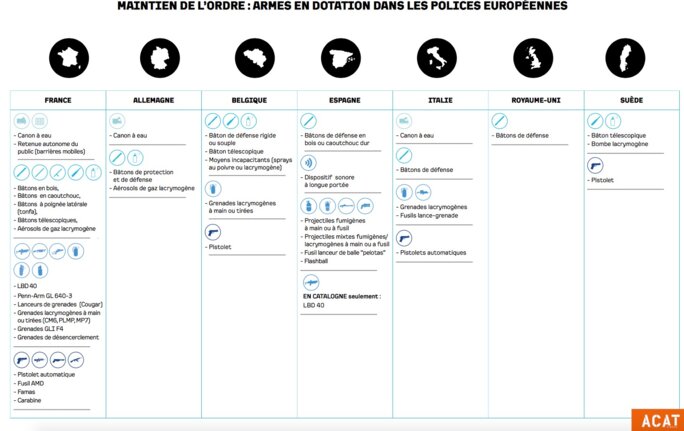

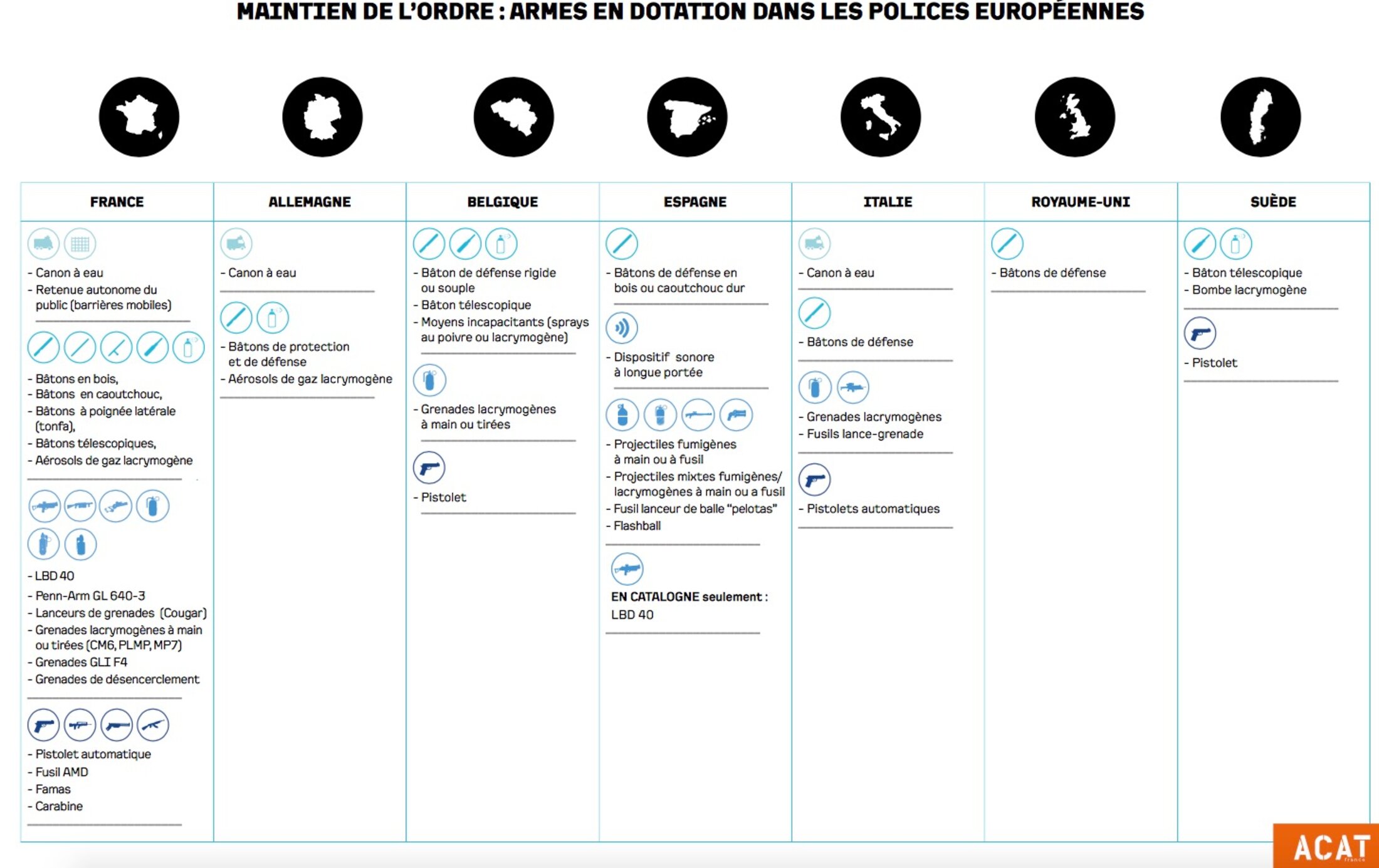

From abuses to indulgence, from silence to encouragement; from this point of view France is becoming an exception within Europe, with a more violent and aggressive maintenance of law and order carried out by security forces who are over-equipped and over-armed. And whom the government plans to over-arm even more, as shown by these new orders for projectile launchers.

'Only firearms remained unused'

As well as this comparative chart (see below) which highlights this dangerous French exception and which was recently released by Action by Christians against Torture (ACAT), one must add the analysis of the sociologist Fabien Jobard – a specialist on the police - who underlines the “considerable scale” of the repressive actions taken against the yellow vests. He says: “The police interventions have led on many occasions to considerable damage: hands blown off by grenades, disfiguration or loss of an eye caused by shots from self-defence ball launchers, a death in Marseille: the toll has gone beyond anything we've seen in metropolitan France since May '68, when the levels of violence and protestors' weapons were far higher, and the level of protection of the police quite simply ridiculous with regard to what it is today.”

Yet “in maintaining order it's the giver of orders who is in the front line, in other words the politician,” says Jobard, highlighting how this “political interference in the management of police forces is a distinctively French characteristic”.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The sociologist continues: “It's less the police who are implicated here than the weaponry that they have and the orders that are given to them. You don't find in Europe, in any case not in Germany or Great Britain, equipment such as explosive grenades and self-defence ball launchers, which are weapons that mutilate or cause irreversible injuries. To use these weapons faced with inexperienced protestors many of whom (and we saw this when they appeared for summary trials) were in Paris for the first time, brings a dynamic of radicalisation which drags the two camps into a very dangerous escalation: one side is convinced that they are responding to excessive and therefore illegitimate violence, and the police, seeing themselves attacked, use all the means at their disposal.” Finishing this warning he adds: “Only firearms remained unused.”

Fifty years ago, when the government of Charles De Gaulle was shaken to its foundations in a much more serious manner, the head of police in Paris, Maurice Grimaud, had no hesitation in addressing all police officers on May 29th 1968 to warn them against “excesses in the use of force” (see here on my blog).

“After the inevitable shock of contact with some aggressive demonstrators who have to be pushed back, the men of order that you are must immediately regain their self-control,” he wrote. “To strike a demonstrator who's fallen on the ground is to strike oneself, by behaving in a way that harms the whole police profession. It is even more serious to hit demonstrators after arrest and when they've been taken to police stations to be interrogated … Be very aware of this and repeat it around you: every time that illegitimate violence is committed against a demonstrator, dozens of his comrades will want to avenge him. This escalation has no limits.”

No one in authority has said this in recent weeks! It is as if the guardian role provided by the senior civil service against the partisan excesses of the state's temporary occupants has disappeared. As if it had been abandoned out of servility or through fear. Or, worse, as if it had itself been won over and itself adopted that instinct of proprietorship which characterises our governments drawn from the elite education establishments, convinced that they know better than the people what is good for them, while also unquestioningly serving the economic interests of those who are in a minority in society.

From this point of view the initial event in the Benalla affair – the acts of violence carried out on May 1st – will remain as the emblematic absurd scene of this worrying downward spiral we are seeing. An entire administrative chain, from various senior civil servants right up to the president of the Republic himself, showed indulgence (to use the word employed by Emmanuel Macron himself) - or even became accomplices by keeping the affair quiet until revealed by the press - towards behaviour that is usually reserved for authoritarian regimes – namely, an aide of the head of state helping the police to strike and arrest opponents.

At the highest echelons of state they seem to be quietly saying that no quarter should be given to the masses, thus repeating the tragic error of democratically elected governments who come to dislike their own people. So, far from protecting us from the arrival of authoritarian governments, they pave the way for them: firstly by making normal the brutalisation of rights and of fundamental freedoms; and secondly by despising all popular expression which then falls back onto resentment and bitterness.

A distant historical event sheds light on the nature of this mistake. When the Second Republic came into being after a long imperial and then monarchic pause, it drowned the democratic and social hopes of February 1848 in blood through its merciless repression of workers revolts in June 1848. What happened next, alas, in December 1851 was the indifference of a large section of the people to the killing of the Republic by the future Louis Napoleon III, who was at the time the elected president of the Republic.

It was the denial of the democratic and social aspirations that came from the people that had led to the end of the Republic, the coming to power of an individual taking away the wishes of all. The entire problem today is that the Macron presidency behaves as if it was already this confiscatory power.

Pretending to ignore the circumstance of his election to the presidency in 2017 – it was against the far right in the second round having attracted a base of only 18% of registered voters in the first round – which should have obliged him to take into account the political and social diversity of the expectations of which he was now the custodian, Emmanuel Macron behaves as if he had been handed a blank cheque for five years. Yet if there is indeed one political issue on which the clearly contradictory plurality of the yellow vests is not confused, it is the rejection of this locking down of democracy by the presidency.

You elected me in 2017, so there will be no alternative to the policies that I have decided upon until 2022. That is the Macron credo. It is a credo repeated over and over again even as he purports to be inviting the country, under the pressure of the yellow vests, to take part in a great national debate. But as his allies quickly pointed out it is a debate which must not challenge the policies that are being carried out. This approach was summed up humorously by the socialist MP Boris Vallaud: “Let's all debate together the [political] line that I have decided all on my own not to change.”

This stubbornness risks ruining the credibility of the Commission Nationale du Débat Public (CNDP), the independent body whose job it is to give people their say on issues, and which was chosen to run the government's 'great debate' due to start on January 15th. There must be a fear that this body will not be listened to by the government if it decides to raise questions over some of the government's ideological bases such as, in particular, its decision to favour the wealthy and big capital. [Editor's note, since this article was written the CNDP's chair Chantal Jouanno and then the CNDP itself pulled out from running the debate after a row over the level of her pay.]

When some yellow vest protestors refer to 'Maidan', the Ukrainian revolution of 2014, or to the women's march to Versailles in October 1789 (popularised in the recent film by Pierre Schoeller, Un Peuple et Son Roi – known in English under the title 'One Nation, One King') they are showing that their movement cannot simply be reduced to the hate, the excesses and the agitation that are quickly blown out of proportion by a form of political and media panic.

For as reprehensible as they are right now, as worrying as they might be for the future, they do not tell the truth about a popular surge that is completely unprecedented: for the first time in our history a social movement has taken hold of the issue that is usually reserved for specialists on the Constitution or confined to the margins of political debate, namely that of our democratic vitality which has for so long been suffocated by the presidential system.

If the yellow vest protestors shout “Macron resign” it is because having given up on his promise for a “profound democratic revolution”, and having added to it the lofty disdain of those who consider themselves to be “too intelligent”, he symbolises the persistent refusal of the elites faced with this urgent situation: a refusal to reinvent a living, deliberative and participative democracy, with strong counter-powers, a truly independent justice system, a Parliament controlling the executive, a genuinely free press and so on.

If, here or there, their anger turns to bitterness it is because this demand is clearly not being heard. Yet is is indeed through failing to deliver on this issue, under all preceding presidencies since the warnings provided by the head-to-head contest between President Jacques Chirac and far-right Jean-Marie Le Pen in 2002 and the European referendum whose vote was betrayed in 2005, that has helped the extreme right.

Having started as a revolt against the cost of living, the yellow vest movement is making a confused demand for a new democratic lease of life, for sharing and exchanging, in place of the top-down nature of the presidential system. To respond to it with additional repression proves the government's weakness and demonstrate its irresponsibility. Yes, their irresponsibility, for far from calming things down and bringing people together, this is the route that causes division and aggravates the situation.

This warning has already been given by the pacific activists from 'Partager c'est sympa' ('It's good to share') when video maker Vincent Verzat gave the group's New Year's message for 2019 on Mediapart and said: “Those who make a pacific revolution impossible will make a violent revolution inevitable.”

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this comment article can be read here.

English version by Michael Streeter