It is not that other European nations are no longer shaped by their colonial past, by how it is remembered, and by their cultural heritage. But in France the issue of colonialism is still an active and concrete political issue, still determining ideological debates and government positions to this day. A close examination of the subject shows that it is a crossover point for social issues (the make-up and renewal of the working classes from the impact of relationships, social interaction and migration from elsewhere), democratic issues (the merger, under the impulse of a presidential monarchy, of a vertical power structure with a 'sameness' of identity) and international issues (France's relations with the diversity, plurality and fragility of an interdependent world where the universal is constructed through interaction and sharing rather than through domination and submission).

This persistence of the colonial issue sets France apart from the other former continental powers who helped project Europe onto a world in which, as well as amassing wealth through the crude accumulation of capital, they also invented the West in political terms as the yardstick, judge and model for the other peoples and cultures on whom they imposed themselves through force and conquest. French decolonisation has not just been the slowest (except for Portugal, where it came 12 years after Algeria's independence from France in 1962), but also the least consensual (the period from 1945 to 1962 marked 17 years of uninterrupted French colonial wars, from Madagascar to Algeria, and including Indochina), and the least complete (France is now the only direct colonial power with overseas départements or counties and territories).

Enlargement : Illustration 1

At the end of the 18th century and during the 19th century, the British and Spanish empires were soon forced to transfer sovereignty to some of their own colonies, which themselves used slavery; the United States for the former and South American nations for the latter. It was very different with France whose colonial jewel – then called Saint-Domingue, now Haiti – was the setting for the fourth critical revolution, carried out by slaves led by the 'black Spartacus' Toussaint Louverture. The radical nature of this revolution subverted the other three key revolutions: the Parliamentary one in England, the independence one in America and the Republican one in France. It was a revolution for which the Haitian people would literally pay the price, having to hand over huge financial compensation to France until the middle of the 20th century.

As for Germany and Italy, they lost their colonial empires in their European defeats, after the 1914-1918 war for the former and after the 1939-1945 war for the latter. France, meanwhile, only managed to find itself at the victors' table in 1945 – this after the majority of its political, economic and intellectual elites had agreed to collaborate with Nazism – thanks to the call-up of solders from its colonies, who provided the bulk of troops for France Libre or Free France, that unlikely army on which Charles de Gaulle's legitimacy was based.

Finally Portugal, which was the first European country to seek out and conquer distant lands, was also five centuries later the nation whose decolonisation process was synonymous with democratisation. In 1974 the Carnation Revolution that put an end to the dictatorship of António de Oliveira Salazar was led by soldiers involved in the country's dirty wars in Africa; in Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau and Cape Verde. In contrast, France's final colonial crisis – the Algerian war – led in 1958 to an attempted military coup against the democratic regime in the ultimately vain hope that France would keep its colonial empire. Instead, the coup led to the creation of the current Fifth Republic, which was once described as a “permanent coup d'État”.

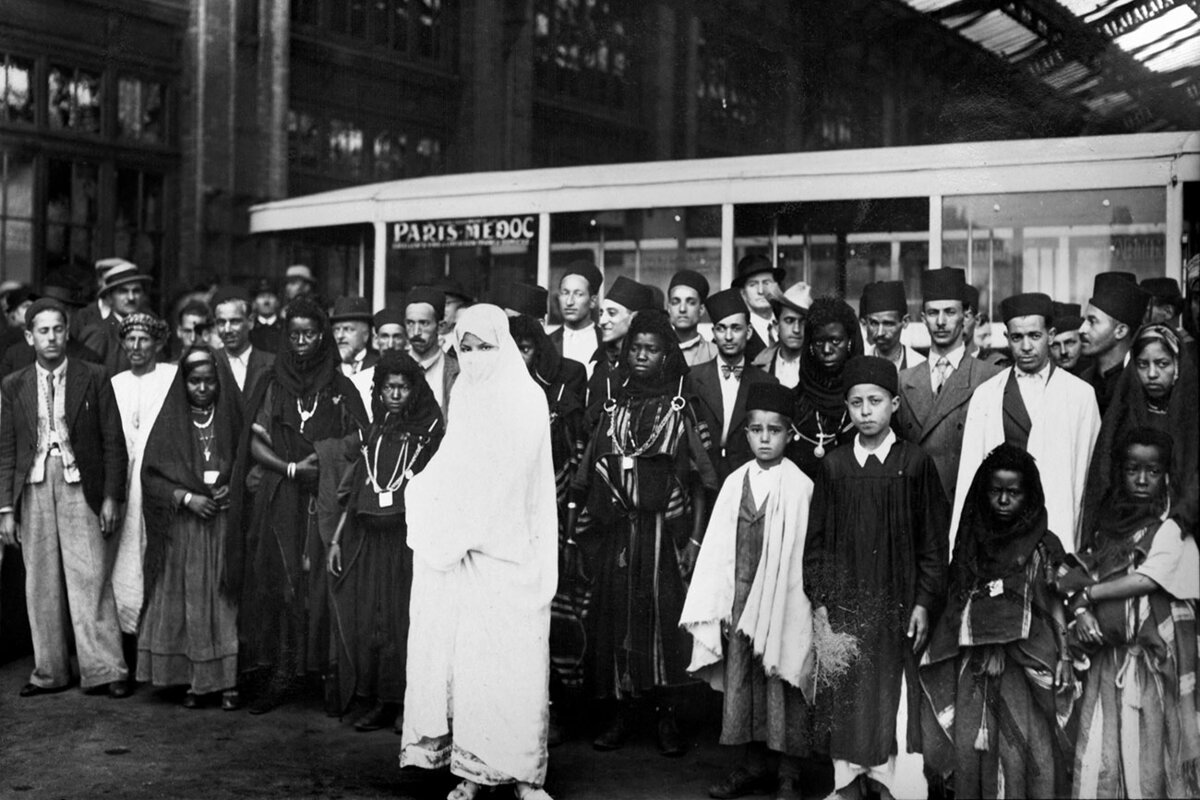

In 2015 a major study by the French Institute for Demographic Studies (INED) on the diversity of the French population established that 14% of the French population were born outside of mainland France and that a further 15% were directly descended from migrants, residents in the overseas départements and territories, or French people born outside mainland France. On top of these nearly one third of inhabitants with some kind of link to France's colonial history, one must also add all those who, without being descended from it, were involved in this projection of France outside its continental mainland – in particular during the decades of its slow and painful decolonisation. INED also showed the extent to which people linked to colonial migration felt more involved than others in national politics, demanding civic inclusion while at the same time having the diversity of identities that makes France a multicultural nation.

France is the outlier of European colonialism as 18% of its territory is overseas and, thanks to these far-flung lands, it has the second largest maritime domain on the planet after the United States.

Moreover, France is the last direct colonial power in the world in the 21st century, the only nation whose flag, the tricolore, flies on every continent, from French Guiana to New Caledonia and Polynesia, and from the French Antilles to Mayotte and La Réunion. France is thus the outlier in European colonialism as 18% of its territory is overseas (making up 4% of its population) and, thanks to these far-flung lands, it has the second largest maritime domain on the planet after the United States. This is not just an historical anomaly in relation to people's right to self-determination, a right recognised by international treaties and conversations since World War II, it is also an exception which – paradoxically – makes France blind to itself. As a result of this colonial prejudice it refuses to recognise its multicultural dimension, the diversity of its origins and its plurality of cultures.

On top of this cultural blindness, this continuing direct colonialism also results in actual conflicts, of which New Caledonia has been at the epicentre for four decades. This was marked in 1988 by a deadly military assault against independence-seeking Kanaks at Ouvéa, and has continued since through a series of agreements on a process of self-determination which has not yet reached its conclusion. To this we should add the recurring uprisings, specific to the overseas territories and départements which, like the movement against “profiteering” in 2008 and 2009 in French Guiana and then the French Caribbean, have inspired and breathed life into popular protests in mainland France. An example was the occupation of roundabouts by the 'yellow vest' protestors in mainland France in 2018 and 2019, which was also itself a protest against the cost of living.

This resistance to authoritarian orders from a central government that places itself above society has been further illustrated during the current coronavirus health crisis, for example when the lingering legacy of the colonial past actively hampered the vaccination process in Martinique. Amidst the confused diversity of the popular protests, this gave us a glimpse of how an old colonial mindset determined the relationship of those in authority to the territories they governed. Rather than understanding France as a multicoloured patchwork, woven by diverse situations, the authorities simply see it through the prism of a state uniformity that mistrusts local sensitivities or treats regional authorities like children. In this we can see the same mistrust of France's Third Republic (1870 to 1940), which was then resolutely colonialist in its external policy, in relation to the 'petites patries' or 'little countries' that made up mainland France, from Brittany in the west to Occitanie in the south.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Almost half a century ago, in 1976, a series of lengthy articles appeared in the newspaper Le Monde about the far-flung scraps of land or “confetti” that made up France's “empire”. The series started with this question: “Is France the last colonial power in the Western world?” It continued: “The question might startle many French people of good faith, who think that after the independence of Algeria and the countries of black Africa, the 'colonial file' was closed a long time ago.” In fact, since 1962 the governing French elites and their intellectual and media representatives have turned the colonial issue into something of a blind spot in terms of public debate. It is as if after the granting of independence the issue has been got rid of for good; and that having been handed over to the newly-sovereign populations it no longer exists in the former colonial power itself.

Indeed, the book 'Les Lieux de mémoire' (literally 'sites of memory' which has been published in English under the title 'Realms of Memory'), a lengthy collective work that appeared under the overall editorship of historian Pierre Nora between 1984 and 1992, does not dwell on any aspect of France's imperialist past apart from the 1931 Paris Colonial Exposition. The 'code noir' or 'black code' defining the conditions of slavery, the long duration of slavery itself, the Haitian revolution, colonial conquests made by the French Republic, the Algerian war; none of these featured in this monument to a history that was intrinsically rooted in the stifling and eternal nature of a 'national identity'. This identity excludes diverse and faraway places, even though these have helped create both France's past and its present.

As the Belgian historian Marcel Detienne highlighted in L’Identité nationale, une énigme, published by Gallimard in 2010, this deletion of the past paved the way for a revival of the idea that the nation is based on “sameness” (“being the same and staying the same”), whose symbolic violence towards populations that show the diversity of France has legitimised and reinforced an all-too-real state violence, particularly on the part of the police.

The 2017 publication of Histoire mondiale de la France, edited by Patrick Boucheron and published by Seuil, provided a welcome counterweight to this approach. It discusses, for example, the “French version of 1492” during the reign of King Louis XIV, who combined “a crusade against Islam in the Mediterranean, religious purification, conversions and expulsions [of Protestants], the organisation of mass slavery, supremacist ideology”, in a section written by Jean-Frédéric Schaub. In a section by Manuel Covo it recalls how in 1791, when the revolution of the 'black Jacobins' began, Saint-Domingue was the leading producer of coffee and sugar in the world, representing most of France's colonial trade thanks to the forced exploitation of 500,000 slaves, two thirds of them born in Africa and supplied by an intensive slave trade that was the basis of the prosperity of the major French ports of Nantes, Bordeaux, Le Havre and Marseille. And in a section by Sylvain Venayre the book analyses the well-known lecture on the nature of nations given by French historian Ernest Renan in 1882, at a time when the Republic was adopting colonialism. When read today its language “makes integration into French society difficult for those who come from elsewhere and who don't recognise themselves in [that society]”.

But this response by other historians has not been enough to reverse the trend of a public debate that is determined to bury the colonial issue, to remove or discredit it. Thus we had the attempt to praise the “positive role” of colonisation (in legislation that was voted through in 2005 then repealed the next year by President Jacques Chirac), the stigmatising under President Nicolas Sarkozy of the idea that one might “repent” for colonialism, the demonisation of “separatism” in current legislation under President Emmanuel Macron, and an attack on “decolonial” thinking in universities, seen in one recent appeal issued by a group of intellectuals and in another signed by the historian Pierre Nora, and so on. This tension on the part of 'official' French, which has waged war against any statements or claims about the colonial issue, bears witness to the powerful revival – through the expression and activism of those most involved – of the very subject that 'official' France has worked so hard to suppress.

This is very different from the situation in United States, where the persistent reminder of the country's slavery past through racial segregation provided the setting for a political and intellectual awakening in the 1960s which widely permeated progressive forces who demanded emancipation. There was nothing like this in France, where anti-colonialism has always stayed on the political margins, taken up by dissident and minority figures, even if their intellectual aura meant they shone abroad – an example being France's surrealist movement.

It is no coincidence that, at a time when the truth concerning France's colonial issue is now being highlighted, a nationalist refrain has struck up on both the Right and the Left in a bid to discredit a supposedly harmful 'Anglo-Saxon' influence at play. Its symbolic scapegoat is 'wokism'. However, beneath this caricature – which has a whiff of xenophobia about it - 'wokism' is simply the concrete expression of the common cause of equality. It brings together rainbow coalitions of all the best intentions of activists as they tackle class, race and gender oppression.

There is a risk that this long French delay in tackling the issue will come at a heavy price. For it is from this fertile soil that the “great replacement” theory has sprung, this deadly ideology which has fed a rebirth of neo-fascism, sometimes terrorist in form, and whose inventor Renaud Camus and propagandist Éric Zemmour are both French. This concept, which is now aired in public debate, is a call for the annihilation of French plurality, which it is claimed presents a deadly threat.

Its motivation is of the same kind as the modern anti-Semitism that had already taken shape in France by the end of the 19th century, at the same time as the Republic was choosing the path of colonial expansionism; the anti-Semite Édouard Drumont, author of La France Juive, was then a Member of Parliament for Algiers. This book, which became a big hit at the time of its publication in 1886, sets out a delusional vision of a nation invaded from the inside by Jewish 'otherness' and was the first ideological foundation of European genocide. This genocide was later committed by Nazi Germany with, among others, the collaboration of France under the Vichy regime of Marshal Philippe Pétain.

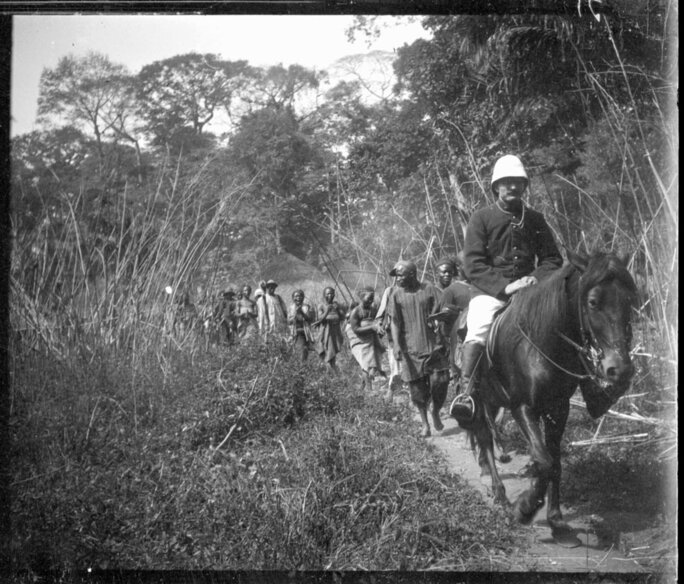

Enlargement : Illustration 4

We have certainly not reached that point. But all the while it continues, the repression of the colonial issue exposes France to disastrous decline, weakening the antidotes that exist to the renaissance of racism. From this point of view the belated acknowledgement – in President Jacques Chirac's Vél d'Hiv speech in 1995 – of France's own responsibility under the Vichy state for crimes against humanity, whose victims were Jews in Europe, remains unfinished business.

In her book The Origins of Totalitarianism the political theorist Hannah Arendt describes imperialism as the crossing point between anti-Semitism and totalitarianism. Nazism was an exterminating form of colonialism, with the imperialist violence that had previously been unleashed on the continents of the colonial conquests now turned on the European continent itself, where it targeted populations, cultures and civilisations held up as inferior or alien.

Nazism brought together and fused two paradigmatic figures: the Jew, the 'other' of the Western world, and the subhuman, the 'other' of the colonised world.

Continuing on from Arendt's seminal approach, the Italian historian Enzo Traverso writes in 'The Origins of Nazi Violence', published by The New Press in 2003, of the “European roots of National Socialism”. In doing so he goes against the tendency, which persists in France, to want to “eject the Nazi crimes from the trajectory of the Western world”. The historian portrays “colonial violence as the first implementation of the exterminatory potentialities of modern racist discourse”. He goes on to add: “There is no attempt here to blank out the uniqueness of Nazi violence by simply assimilating it to the massacres of colonialism. But we do need to recognise that it was perpetrated in the middle of a war of conquest and extermination waged between 1941 and 1945, which was conceived as a colonial war within Europe.” Enzo Traverso also states: “Nazism brought together and fused two paradigmatic figures: the Jew, the 'other' of the Western world, and the subhuman, the 'other' of the colonised world.”

The French Left has never been resolutely anti-colonialist, except for a minority on the margins or during short-lived bursts. In fact, French social democracy, through the role of the French Section of the Workers' International (SFIO), the ancestors of the current Socialist Party, bears responsibility for the colonial wars which, especially in Algeria, delayed independence by accepting the committing of crimes. The widespread use of torture there still remains the cruel symbol of this approach. Yet none of the political leaders involved had to answer for what happened there. Indeed, one of them, Robert Lacoste, who was resident minister and governor general of Algeria from February 1956 to May 1958, later continued his career as a Member of Parliament and then a socialist senator for the Dordogne in south-west France until 1980, dying in 1989 at the age of 90.

Beyond this unpleasant example, the credo of the French Left in general has for the most part been assimilationist. It has supported the cult of a Republic where the 'oneness' of state authority (presidential power) is also 'sameness' (national identity). Neither of its two great families, the socialists and the communists, protected themselves from this profoundly colonial ideology which demands that 'otherness' rids itself of that which makes them who they are, their individuality, their distinctiveness.

Even when expressing solidarity they reveal a reticence to let those primarily involved to organise themselves, citing a “fraternalism” which is both condescending and dominating. It was this approach that Aimé Césaire, the poet, author, and politician from Martinique, criticised in his 'Letter to Maurice Thorez' - the French Communist Party's general secretary - at the time of his break from the party. The recurring tensions over prescriptive secularism, which betray the liberal promise of France's 1905 law which separated church and state and granted freedom for minority faiths, and also the recent row over 'non-mixed' meetings, all illustrate this oppressive tendency. Today it is the Muslim section of the French population who are paying the price, being called on to be 'less' (Muslim) in order to become 'more' (French).

In fact, the embodiment today among activists of this rejection of the colonial issue, of how to resolve it, is a network that comes from the ranks of the Left: 'Printemps Républicain' or 'Republican Spring'. Its ideology marks a retrograde step which takes us back to the previously-cited 1882 lecture by Ernest Renan, who was then the recognised thinker for the Republican movement. The lecture's title was: “What is a Nation?” and the response: “A soul, a spiritual principle … a daily referendum.”

Yet a decade before the same Renan wrote, in his work 'The Intellectual and Moral Reform of France': “Colonization on a grand scale is a political necessity of absolutely the first order. A nation that doesn't colonize is irrevocably doomed to socialism, to war between rich and poor. The conquest of a nation of inferior race by a superior race, which establishes itself as the ruler, has nothing shocking about it … While conquests between equal races must be disapproved of, the regeneration of the inferior or bastard races by the superior ones is consistent with God's plans for humanity.”

These words and comments, which today would be taken to be those of the far-right, were 'Republican'. So it is not enough just to brandish “The Republic”, a Republic without adjective, neither democratic nor social, that is ignorant of its past faults and crimes, to raise the prospects of hope today. Still less can one portray France as a universal exception that can keep raising the bar for other nations in order to meet the challenges and urgent demands of the world. It is in fact quite the opposite; such a course guarantees stalemate and powerlessness.

While the recent Afghan disaster reminds us that no people can be converted by force to democratic ideals over which the West claims a monopoly while trampling all over them in its bellicose madness, the French Left must also remember that the long presidency that they claim as their own, the 14 long years of François Mitterrand at the Élysée from 1981 to 1995, was also marked by a continuing blindness over colonialism. It started in 1982 with an amnesty for the French generals who had attempted a putsch in 1961 because they opposed independence for Algeria, and ended in 1994 with the presidency's compromising behaviour towards those who carried out genocide in Rwanda.

While these two facts do not sum up that presidency, they still highlight the legacy that clouds the prospects for the Left's future. It urgently needs clearing.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter