A lack of doctors and administrative shortcomings by at least one health authority helped contribute to the grim situation faced by many care homes in France during the coronavirus epidemic, a Mediapart investigation has found.

In one case a doctor says she was banned from a nursing home after she advised a care assistant with Covid-19 symptoms to go home. She said that patients had been put at risk as a result of her being ordered out. In another example the son of one victim said that some residents in care homes were effectively being “sacrificed” because of a lack of personnel and equipment and the nature of the directives handed down from the authorities. “My mother was betrayed by the Republic,” he said.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The first case involves 'Sophie' - not her real name – a doctor who was working in a care home north of Paris. When she returned home on March 26th Sophie wrote down her experiences and the next day emailed her story to the Paris regional health authority (ARS). In the email the doctor revealed that the director of the Les Intemporelles care home at Aubervilliers, north of Paris, had just unceremoniously removed her from the building, where forty or so elderly residents were living at the height of the coronavirus crisis.

Her 'crime'? Sophie had simply advised a care assistant at the home who had symptoms of the Covid-19 virus to go home, and had asked that a resident who also had symptoms should be isolated in his room.

Two days later Sophie returned to the same care home after a nurse there became concerned about a patient whose state of health had deteriorated. The management reacted the same way, chased her out and even called the police. Yet this care home was not exactly overwhelmed with medical help at the time; its own coordinating doctor, nursing chief, one other nurse and a carer were all off sick.

In her second email to the ARS on March 28th Sophie ended with these words: “The director, by banning me from entering, is banning residents from having access to their doctor, he is putting them in danger.”

The deaths were just about to start mounting up at the Les Intemporelles home, which is owned by the Domus Vi group. Mediapart understands that ten residents have so far died, though neither the company nor the ARS has confirmed this. Among those who have died was Sophie's patient. “He didn't see a doctor for several days, didn't eat, had bedsores and was not tested quickly,” said Ouzna Seker, a care assistant and local representative for the CGT trade union at Les Intemporelles. “In the end the management finally got a doctor from the town to come in an emergency. This patient tested positive for Covid-19 and he died. This episode shocked us all a lot.”

So short were they of medical staff that death certificates were sometimes signed remotely by the home's own coordinating doctor who was off sick, after a clinical examination of the deceased by a nurse. “One day we had a death in the morning and we had to wait until 5pm for the nurse to arrive so that she could carry out the examination and send the information to the doctor,” said Ouzna Seker.

Though this practice had at one time been under consideration by the health authorities, these deaths were not certified under the existing legal framework, as many different medical organisations have told Mediapart.

To avoid absenteeism, the Les Intemporelles care home even organised a nursery for workers' children. “It was in a room on the ground floor where the housekeeper and the director came in. It lasted at least two weeks from March 17th,” said Ouzna Seker.

The union representative also said that inside the care home's closed section, where residents wander around, the director adopted a radical approach. “He asked the maintenance person to change the locks on the bedroom doors so they could be locked from the outside,” she said. The home's own doctor and the ARS then made clear they disagreed with this policy. “So he then started to knock through a bedroom door himself,” said Ouzna Seker.

One employee, who wants to remain anonymous, confirmed the incident and said that the handles inside some bedroom doors were indeed removed. “He said that it was for the lockdown, so that people didn't have the freedom to just go out whenever. I don't know if it was wrong or not,” said the member of staff.

The home's director was eventually suspended on April 10th after the regional management of the DomusVi group was informed of the situation. The health and safety authority also sent a letter about the situation to the group and the ARS or health authority. As for Sophie, she has never had a reply to her email raising the alarm with the health authority. Neither the ARS nor DomusVi responded to Mediapart's questions on the matter.

When Gabriel Weisser describes the circumstances of his mother's death at a care home in the Haut-Rhin département or county in north-east France he cries with both sadness and anger. For weeks he hoped that his mother Denise Weisser, 83, would escape the virus, as she had been isolated in her room with a psychological disorder since Christmas 2019. But on April 15th the home's doctor phoned to say that his mother, who had been examined early that same morning, was showing worrying symptoms and had just been put on a respirator.

Despite his shock, Gabriel Weisser nonetheless asked what his mother's oxygen levels were, and was told they were at 85%. “She wasn't perhaps a candidate for intensive care but they could have considered taking her to hospital and giving her medicine. But no, she was put straight on to palliative care in the care home,” he said. Denise Weisser died that same evening.

Gabriel Weisser said he is not “angry” with the doctor and he praised the devotion of the teams at the retirement home where his mother had spent the last thirteen years of her life. “The doctor at the care home reacted as he was told to react,” said Gabriel Weisser. “It's not a problem of an individual but a problem of equipment, personnel and instructions which led some ill people to be sacrificed.”

His anger is largely aimed at the authorities in charge and he decided to make the matter public (see his blog on Mediapart), telling local media about the tragic death, which occurred in a part of France that was badly hit by the Covid-19 epidemic. Gabriel Weisser is also considering joining a class action lawsuit against the health minister and the former director of the Grand Est regional health authority who was sacked on April 8th.

Since the publicity given to the care home, its management says that it has taken on two new nurses from a neighbouring clinic and has called in care assistants and hospital staff to help its teams. “Amid the darkness that has existed since April 15th there has been a glimmer, some things have started to change,” said Gabriel Weisser. “But my mother was betrayed by the Republic which did not give her the opportunity to get the healthcare to which she was entitled.”

Both situations described above raise the same questions. Were care homes equipped to deal with this unprecedented health crisis? Have they been given enough support? Were they monitored enough by the health authorities? “Covid-19 most often entered those establishments which were already in great difficulty,” said one doctor, a former hospital doctor in the west of France who now works in state-run care homes.

The doctor also points to the complex situation they have faced. “Doctors are not callous bastards, we don't fold our arms and leave people to die,” he said. “But we do also question the point in sending patients with multiple conditions and who are very dependent, and some of whom have no relations left in the world, to [hospital] centres, and by doing so allowing the fox into the hen house with the comings and goings between hospital and the care home.”

Doctors banned from intervening in care homes

Another doctor, who was called in to help at an association-run care home in the Hauts-de-France region of northern France three weeks ago, said that Covid-19 had had a devastating impact on residents, with staff, especially the medical team, having been laid low themselves. In this care home three people died, one after another, on Easter Sunday.

“When I arrived virtually all the management were off sick, it was all temporary staff,” she said. “We had school nurses who had come to help out who didn't know all the residents. Yet the absence of the usual staff can have a very damaging knock-on effect.”

At this particular association-run care home the coordinating doctor – who has an administrative role in overseeing the nursing team and advising management on the home's healthcare plan – was “very part-time” as they also worked at a practice in the town. Six of the seven nurses were off sick. For several weeks, too, their usual GPs were unable to come. “The care home received inexplicable directives to no longer allow their regular doctors inside, because they were potentially a source of Covid. But managing 125 residents alone was impossible!” said the doctor.

“We've seen a departure from many rules in the current pandemic. For example, I learnt that some coordinating doctors [editor's note, in care homes] worked remotely, teleworking,” said Philippe Marissal, a doctor for a state-run care home, treasurer of the leading association representing general practitioners in France and president of the primary care body the Fédération des Soins Primaires. “I also learnt that some directors didn't want outside GPs to come in, even barring them access to the care homes.”

Indeed, the Ministry of Health had decided to reinforce temporarily the role of the coordinating doctor (see the document here, which was used by many health authorities) in order to limit footfall at care homes, and these administrative doctors were authorised to “take care of the non-serious patients in the care home”. More serious cases were to be sent to hospital. However, the ministry never explicitly stated that the regular local GPs should no longer go into the care homes.

This approach left it wide open for some care home managers to regard their coordinating doctors as the “only people to intervene and the only people in control”, even if they were sick or part-time, said Philippe Marissal.

For their part coordinating doctors, some of whom look after several care homes at the same time, say they sometimes feel as if they have been sent to the front line “without weapons or ammunition”. In an article on news website Actu.fr on March 27th Nathalie Maubourguet, a doctor and president of the care home coordinating doctors federation FFAMCO (Fédération française des associations de médecins coordonnateurs en Ehpad), said: “We have no equipment and we are not trained in emergency medicine.” However, some health authorities, such as the ARS in the Hauts-de-France, explained that they have funded the increased working time of these care home coordinating doctors, even hiring them part-time.

On top of these administrative problems, it can be hard to spot some coronavirus symptoms, especially among older people, as several doctors have told Mediapart. In places where the virus first started spreading, the lack of initial protective equipment was compounded by the problem of dealing with the unknown. “Some establishments had initial problems with symptoms that no one at first linked with Covid, such as falls and diarrhoea,” said the doctor called in to help in the Hauts-de-France.

The doctor from west France noted: “Geriatric medicine is about follow-up care. Yet in some places we've had to act like emergency doctors. In an elderly person a lung disease can develop without a cough or fever so it's hard to detect, especially when you don't know the patients.”

Such comments make for tough listening for families, many of whom were left in the dark about what was happening to their loved ones in homes. Pierre, whose 86-year-old mother fell ill in an association-run care home in the Ardèche département in south-east France, recalls his astonishment at what he was told when he was phoned and informed that his mother was struggling with a terrible cough. “The nurse told me that they were trying to avoid bringing doctors into the establishment,” he said. His mother was in the end treated remotely by a doctor in the town and then sent to hospital where, at the start of April, she tested positive for Covid-19.

“I'm still extremely shocked by what I've seen in some care homes,” admitted 'Laetitia' – her name has been modified – who has been a local district nurse for 20 years. As her own work with her usual clientele reduced during the crisis, she said it was “unthinkable” for her not to “come and lend a hand”. On April 22nd she was called up to help as a nurse in care homes, and in particular at a Paris care home run by the DomusVi group. “It was a catastrophe,” she recalled. “I worked there for two days, from 8am to 8pm.”

Laetitia, whose role was to provide basic healthcare and dispense medicines, said that “the 70 residents were tested but whether they were infected or not they were all mixed up on every floor, in adjoining rooms.”

The rest of her account is just as alarming. “Three out of four nurses were off sick and so temporary staff were working in shifts. This problem with staff and the constant change in personnel meant that the prescriptions weren't always followed well,” she said. “For example, one resident had antibiotics which she shouldn't have had. There was also a problem with equipment. Because of a lack of dressings some bedsores were not treated. We had to improvise dressings.”

She said that as some residents “stayed confined in their rooms for weeks” some of them became “anxious and their cognitive functions went right down. Some were put on 'prevention' treatment before being tried on antibiotics, which didn't improve their condition.” Laetitia said she had “no information” on the number of deaths. “The lack of transparency [on this] raises questions,” she said.

So what did the health authorities, the ARSs, know about such problems in the most affected regions? Apart from the Hauts-de-France region, which told Mediapart that “from mid-March” it mobilised reserve healthcare personnel in the region to assist care homes, we have received virtually no response. Even though there were care homes in the Paris region which lacked the staff and ability to deal with the epidemic – despite the ARS issuing a reassuring press release on its website on April 6th – the health authority was even slow to accept help when it was offered by mobile teams of doctors and nurses.

When informed about the situation on April 7th, Professor François Boué, head of the internal medicine and immunology unit at the Antoine-Béclère hospital at Clamart south-west of central Paris, sent an email alert to the director general of the country's health service, Jérôme Salomon. He wrote: “There is a real lack of personnel in the care homes. It's a bit difficult to know who's really driving that in the Paris region, even if we are in daily contact with the ARS who ask us what we are doing and who I ask in return what they are doing: blank space … there's clearly been a delay in getting going on this issue.”

Professor Boué added: “We have some GPs who are offering to the ARS to set up mobiles teams with nurses to intervene in care homes. Response from the ARS: it's not yet in the 'doctrine'.”

It was not the head of the health service Jérôme Salomon who replied ten days later but the director general of the Paris region ARS, Aurélien Rousseau. The regional health boss sought to reassure the professor. “Close to 2 million masks have been distributed to care homes in the region,” he wrote. On personnel levels he said that “exceptional resources have been put at the disposal of the care homes”. He concluded: “The Île-de-France [editor's note, Paris region] regional health authority has been mobilised non-stop since the first day to halt the progress of Covid-19, most particularly among elderly people who are its main victims.”. »

Health authority aware of reporting bias over death figures in care homes

Enlargement : Illustration 2

However, the facts contradict this public relations exercise by the health authority. Even though there had already been more than 1,400 deaths in nursing homes across France by April 3rd, the Paris region ARS rejected that offer by GPs to work as a team with nurses inside care homes. “They replied to me that it was not in the ARS's 'specifications',” said 'Pierre' – his name has been changed – a doctor in the Paris region behind the scheme, who received the reply on April 6th.

It was only on April 15th, after several hospital doctors made their views known to the ARS management, that the health authority finally accepted the support of these mobile teams. Pierre still cannot get over it. “In the middle of a crisis there was an urgent need to come to the help of staff in these establishments who, in some cases, had no doctors left as they had been infected with the virus themselves,” he said.

It was early on in the epidemic that the doctor had wondered how he might get involved “on the ground”. He explained: “As patients were no longer coming to my practice, I called the accident and emergency units at several hospitals but they already had a lot of volunteers.”

The issue of care homes and their needs was then raised on March 17th at a meeting in the Paris region of doctors from geriatric units, epidemiologists, and infectious disease specialists. “We then thought about the measures that would be most adapted to respond to what was looking like it was going to be a healthcare tragedy. We organised ourselves as volunteers,” said Pierre. The mobile teams are made up of around forty doctors and nurses.

Yet even after the mobile teams were ready the “many attempts” to get the ARS involved proved “time-consuming,” said Pierre. The GP said he is still “staggered by the refusal of this authority which is supposed to anticipate and handle health crises”. The health authority did not even provide them with a list of care homes which would have enabled them to work faster. “So we built our own network and called more than 80 establishments,” said Pierre. “And in the end it was the ARS which asked us to give it feedback on the care homes, even though its job is to monitor the proper functioning of those establishments.”

The initial refusal of help by the ARS, its slowness to reach even a modest agreement, and its lack of support for the volunteer team made the new group's task difficult and perhaps even pointless. “We got there too late, at a time when there had already been six to twenty deaths per care home. It was a real emergency,” said Pierre.

The GP also referred to the contradictory orders that the nursing homes received. “Initially the [coronavirus] tests on residents were limited to three, because of a lack of sufficient numbers of tests, and they were asked to send the fewest people possible to the hospitals in order to preserve intensive care beds,” he said. “Then there were inconsistent [treatment] protocols under which some residents were put on antibiotics or on a drip without even being tested. Some, who were isolated in their rooms, died through a lack of treatment or after unsuitable treatment.” And when the testing campaign started “there were already many deaths, and in some establishments there were even no more coordinating doctors, who had become infected themselves,” said Pierre.

That was the case in a care home owned by the Korian group, which describes itself as managing “Europe’s leading network of nursing homes”, at which the GP did some work. “It was a quality place but it's often these groups which have the greatest shortage of staff. And they rarely respond positively to our calls,” Pierre said. “Out of 43 care homes that we contacted, only three asked for help. Yet, while some told us 'it's all going well', we knew there were deaths and a need for staff to administer treatment.”

When Mediapart contacted Professor François Boué from the Antoine-Béclère hospital in the south of the Paris region he was still angry about the situation. “Not only did the ARS not support these mobile teams of volunteer doctors and nurses, it also asked hospital doctors and nurses for assessments - coordinated by a geriatrician - on care homes judged to be in great difficulty, even though we were ourselves working flat out.”

It was indeed much later, in the second half of April, that the ARS finally asked a number of hospital geriatric units to coordinate teams of GPs and hygiene nurses and send them to care homes it listed as priority cases.

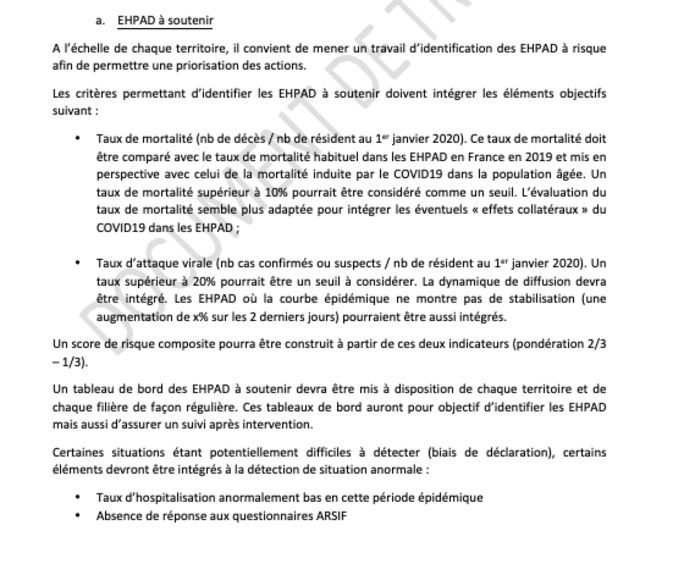

But even here there are doubts as to the way in which the health authority supervised this work. Mediapart has seen an internal working document from the Paris region ARS dated April 15th and entitled “Strategy for hospital support for Paris region care homes”. It discussed the methods of “detecting the care homes to support and prioritising interventions”. The ARS acknowledged that in some cases the fragility of care homes “existed before the Covid-19 epidemic … [which] probably destabilised an already precarious balance”.

In order to define the “care homes at risk” the authority relied on two sets of data. One was the mortality rate in which the threshold was considered to be a rate above 10% compared with the same period in 2019. The other was the “viral attack rate” which is the number of confirmed or suspected cases of Covid-19 infections in relation to the number of residents as of January 1st 2020.

In addition, they looked at “factors favouring” the spread of the epidemic, such as “human resources difficulties (absenteeism rates)” and “management shortages”.

But the ARS note stated that when it came to mortality rates “some situations are potentially difficult to detect (reporting bias)”. This shows that the health authority was already aware of the lack of transparency in some establishments over the number of deaths they were notifying. But despite this lack of openness the authority did not advise on the need for inspections, even though this is provided for its own terms of reference.

On the other hand the ARS did advise taking note of other data which it said were symptomatic of an “abnormal situation”; the “abnormally low rate of hospitalisation in this period of epidemic”, the “absence of responses to the ARS's questionnaires” and the “flagging [of issues] by mobile geriatric teams”.

A professor of geriatrics who asked to remain anonymous said: “The ARS went on information which it acknowledged itself was incomplete. Management at care homes often say that everything's fine. But rather than go and see, the ARS relied on figures which meant nothing.”

For example, he said, the rate of hospitalisation is not a good indicator. The rate stayed low for weeks because of directives from the Ministry of Health which on March 19th, in a memo revealed by the investigative weekly Le Canard Enchaîné, suggested than the admission of the most elderly patients to intensive care units should be limited.

Professor François Boué from the Antoine-Béclère hospital said that he had received a list of care homes judged a priority by the ARS, which consisted of “four out of around forty establishments. It's not just the low number that raises questions. None of the four was appropriate. Other care homes were in a much more worrying situation. But that information, unlike the ARS which was happy with the declarations made by managements, we got directly via warnings from care staff in those establishments.”

“It's not our role to go and inspect the care homes,” said the professor. “It's difficult turning up like storm-troopers. Not only do we not have the human resources to do that, it's in fact down to the ARS to carry out this task,” said Professor Boué.

“In the end it was often we who informed the ARS about urgent situations which coordinating doctors at the establishment had passed on to us,” he said. The professor is also unhappy that when reinforcements did arrive it was too late. “The care staff, like the residents, had been infected and carrying out massive numbers of tests after the battle didn't serve much purpose,” he said.

'We're scared for our parents'

There are thus question marks over why the Paris region health authority did not carry out inspections inside care homes, and about the handing over of its own responsibilities to other groups. As a precaution the ARS took care in its recommendations published on April 17th to remove anything that might suggest they had indeed known about the lack of transparency over the deaths in care homes. There is no trace in these recommendations of the “reporting bias” it had referred to in the internal memo.

Transparency has not always been provided to families either. Ambroise Védrines lost his grandmother to Covid-19 in a care home in the département or county of Seine-Saint-Denis north of Paris. “The director himself admitted that he had lost control of the situation, with more than half of the staff off sick and lots of temporary staff. That clearly shook it very hard,” said Ambroise Védrines. “But my grandmother departed without suffering, and in dignity, thanks to the intervention of a doctor from the town.”

However, what did shock Ambroise was that “there were no tests, and no way of going faster to detect what wasn't working well” in a small care home which was virtually bereft of medical resources.

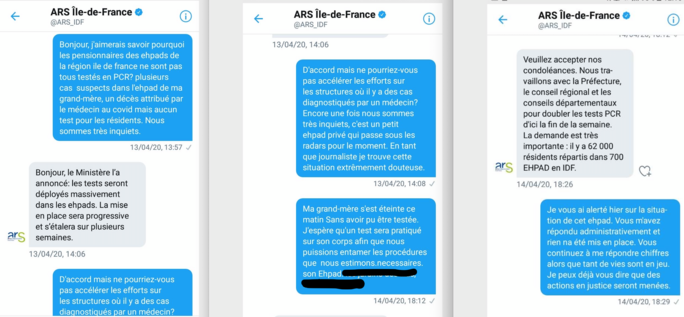

On April 13th, when he learned that his grandmother was ill, he sent distress messages on Twitter, trying to make contact with the Paris region ARS whom he had found it impossible to reach by phone. “They replied, in a semi-administrative and political language, that tests were going to arrive … but by then we needed concrete answers.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Ambroise Védrines used the same communications method and got the same kind of response when he informed the ARS that his grandmother had died, one of around ten who has perished in the home of around 80 residents since the start of the epidemic.

Meanwhile, near Nancy in north-east France, a relative asked the local health authority there on April 6th if tests were due to be carried out in the care home where the person's two parents lived and where a first death had already been recorded. This care home was located not far from another nursing home at Bouxières-aux-Dames where twelve residents had died and a third of the staff had tested positive for Covid-19.

“On the Friday I called the ARS [editor's note, the Grand Est health authority] but they were very hard to get hold of,” said this relative. “Then I tried on Saturday morning. But it was Easter weekend and no one was going to reply to us. I finally only got the ARS on the line on the Tuesday morning and again I was probably calling a call centre. I was told that the measures had been badly understood and that it was up to the care homes to approach the laboratories to carry out their tests … during this time we were scared for our parents.” The tests were finally carried out a week later, after pressure from families and after several contradictory pieces of information.

There is no doubt that the health authorities, especially those in the worst-hit areas such as the Paris region and the Grand Est in the north-east of France, had a huge workload managing an unprecedented health crisis. And like other areas of the state these decentralised health authorities, the mainstay for the Ministry of Health on the ground, have suffered lower staffing levels in recent years at the same time as becoming the sole voice on health issues locally both in hospitals and in the wider community.

In addition the ARSs have had to manage the coronavirus crisis in line with the ever-changing directives from the government on masks, tests, lockdown rules and so on.

And these authorities have also had to oversee the vast sector of the care sector and its 7,000 different homes for the elderly, run variously by the state, local associations and the private sector. Decisions have not certainly been applied in the same way in every establishment.

But the misguided nature of the instructions they have sent out and their inability to respond to demands have fuelled concerns about the ability and even the desire of these ARSs to obtain a clear picture of what happens behind the closed doors of these establishments. Mediapart has seen a crisis situation update written by the Paris police on April 9th. It states that the Paris region health authority said it had reminded care homes about the instructions concerning the filling in of questionnaires and declarations. “To this day, 62% of the care homes have responded to the questionnaire,” the document reads. This raises the question as to what happened to the remaining 38%.

When contacted by Mediapart about the reliability of the figures forwarded to them the Paris ARS and also the Grand Est ARS in the north-west and the Rhône ARS in the south of France, all areas badly hit by the epidemic, did not respond. According to the Hauts-de-France ARS, which did respond, the introduction of the new Voozanoo digital platform by the public health body Santé Publique France, enabled them to get “an image close to reality about the establishments”. However, it accepted there could still have been some gaps in the way some deaths have been declared and their attribution or not to Covid-19”, plus gaps due to “transmission delays”.

Michel Parigot, president of the Covid-19 victims' association Coronavictimes, is worried about the “silence” that prevailed for so long in the care home health system, helped by the fact that until very recently families were not allowed to visit because of the epidemic. “The absence of transparency probably comes from the fact that it's difficult to accept responsibility for a situation that you're unable to manage properly,” said Michel Parigot, who has worked on behalf of many victims groups in the past, notably people exposed to asbestos. “You can't put the burden of responsibility on each care home. Yet the government's entire game is to lean on others for its own mistakes.”

On April 2nd this association, which is keen to expose what it sees as the lack of healthcare opportunities provided to older people, especially in terms of access to hospital, filed for an injunction over the rights of people ill with Covid-19, claiming their fundamental freedoms had been put at risk by administrative decisions. The legal action, which related especially to care home residents and people ill at home, focused on the right to hospital access and intensive care, the right to an end of life with dignity and without suffering, and families' rights to have access to the cause of death. The country's highest administrative law court, the Conseil d’État, rejected the application on April 15th.

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter