Five days before the brutal murder of Father Jacques Hamel at a church in Normandy in 2016, regional police intelligence officers were aware of messages written by one of the two men who carried out the attack, Mediapart can reveal.

An agent at the Direction du Renseignement de la Préfecture de police (DRPP) in Paris - broadly equivalent to Britain's Special Branch – came across the messages of a man using the online handle '@Jayyed', later identified as one of the priest's killers Adel Kermiche, on July 21st, 2016. In them he urged attacks on churches and said that with a knife one could “cut off two or three heads” and create “carnage”.

Ironically, Kermiche, who claimed allegiance to Islamic State, mocked the police in his postings, claiming they were unaware of his online presence. In his writings and videos he even mentioned the town of Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray in Normandy in northern France where the priest was later killed.

The agent who found the messages wrote a report and passed it on to his bosses but because of holidays, pressure of work and a slow bureaucratic reporting process this file never reached the France's internal intelligence agency the Direction Générale de la Sécurité Intérieure (DGSI) who oversee France's fight against terrorism.

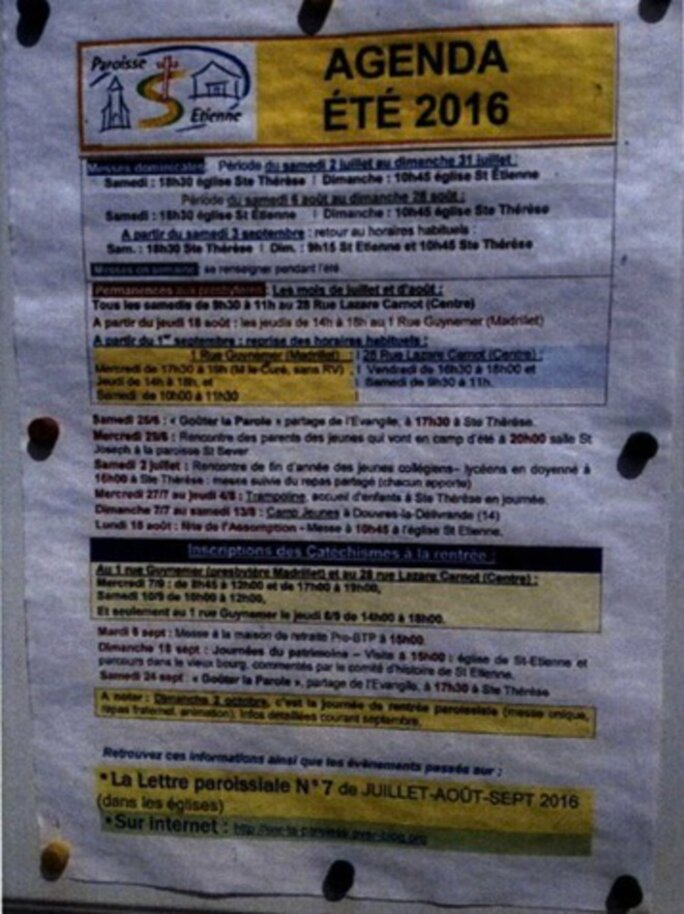

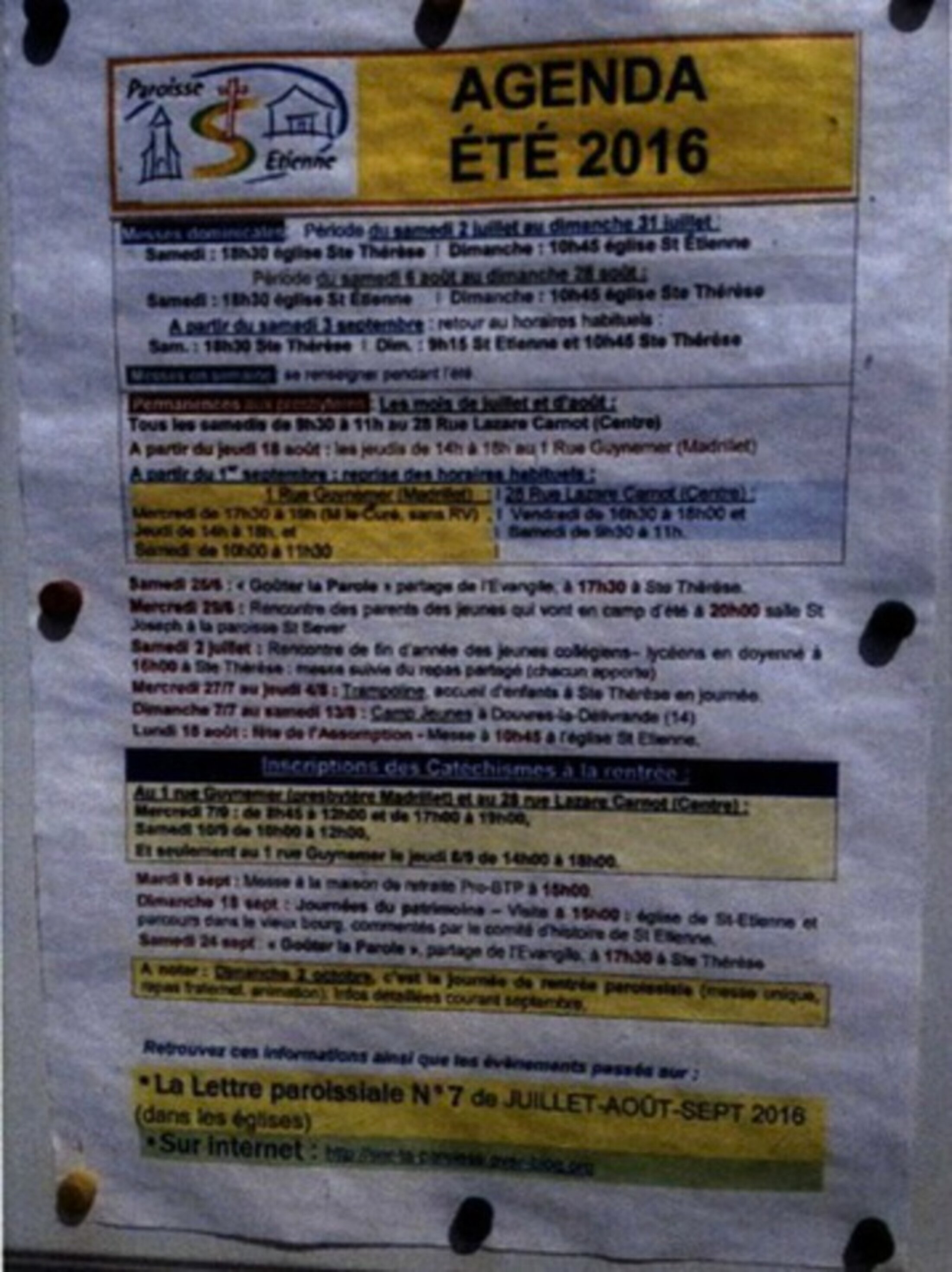

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Just five days later, on July 26th, 2016, 85-year-old Father Hamel had his throat cut by Adel Kermiche and another man, Abdel Malik Petitjean, at the church at Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray. On that morning Kermiche had posted a message to his followers on the Telegram message system that they should “download what's to come and share it en masse”.

Mediapart has learnt that when senior officers at the DRPP in Paris found that they already had a file on one of the two men involved in the murder there was a sense of panic, and they immediately ordered the agent who wrote the report to re-edit it and post-date it to the day of the attack itself.

However, one of the intelligence officers has told Mediapart that this attempt at covering up the true date of the report was itself bungled. “Yes our superiors did indeed try to remove the traces and they did it badly,” the agent said. “There was an attempt at back-pedalling but it didn't work as planned...”

Agents at the DRPP blame a combination of events for the fact that the potentially crucial report was not passed in time to the DGSI, who had meanwhile been on the trail of the other attacker Abdel Malik Petitjean. One reason was the fact that it was the peak holiday season and some key senior officers were on holiday, another that the service was already hard pressed following a string of terror attacks in France, notably the massacre in Nice on the night of July 14th, 2016.

But agents also blame the layers of bureaucracy involved, pointing out that the police intelligence agent who wrote the report was not allowed to contact his counterparts at the DGSI directly by phone but instead had to pass the file up through a chain of four layers of superior officers. “The information remains trapped,” one officer told Mediapart. “Because what one writes is classified as a defence secret, there are too many checks, too many readings, too many chiefs who want to correct the reports, adding their two pennies worth, to give the impression they are adding value to it.”

The agent added: “They hold onto notes because a comma is wrongly placed....The emphasis is on satisfying the superior [officer], one forgets the operational nature of the report.”

The French prosecution services have now opened an investigation into the affair. The preliminary investigation by the Paris prosecutor's office is into alleged “forgery”, “use of forged documents” and the “altering of documents likely to facilitate the discovery of a crime or an offence or the search for evidence by a person ... working to discover the truth”. These offences can lead to a five-year jail term and a fine of 75,000 euros. The press statement (in French) on this from the prosecutor's office can be found here.

Contacted by Mediapart the police authorities in Paris said they would make “no comment on claims from ill-intentioned sources”.

However, the revelations are likely to rekindle the debate about the effectiveness of France's intelligence-led operations against terrorism in the country.

-------

The story centres on the last days in the life of youthful jihadist Adel Kermiche.

Only just 19 and from a local family in Normandy with no radical links, he had nonetheless become, in the police jargon, “a known figure in radical Islamism” in the area of Rouen, the region's capital city. On two occasions, in March and then again in May 2015, the teenager had tried to go to Syria. Arrested in Tunisia, he then spent six months in prison at Fleury-Mérogis to the south of Paris where he did his time alongside well-known jihadists.

Having been released in March 2016 Adel Kermiche was placed under judicial supervision and had to wear an electronic tag. But though this limited his physical movements it did not curtail his activity on social media. On June 11th, 2016, he created his own online channel called 'Haqq-Wad-Dalil' – meaning 'The truth and the proof' – that he ran via the messaging system Telegram. To illustrate it he used a photo of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the self-proclaimed caliph of the Islamic State.

Adel Kermiche hid behind the online name '@Jayyed' though he did post images of himself; on July 17th, 2016, for example he appeared dressed in a camouflage jacket and wearing a black turban. His early postings criticised Al Qaeda and praised Islamic State and showed a liking for anasheed or Islamic songs that have been used by terrorist organisations for their propaganda.

The young jihadist was amused by the fact that he was – or so he thought – acting without the knowledge of the authorities even though he was under judicial supervision. On July 17th, the day he published his photo, Kermiche wrote: “Laughing out loud, I'm hidden. Here I'm not blown, chilled. No suspicion. Glory to Allah, he is blinding them.”

In fact Kermiche was mistaken and Allah was not blinding “them”. For in the following days a police intelligence officer hidden behind his screen was able to monitor all that the young jihadist was saying and writing.

It has to be said that Mediapart was mistaken too. For in a series of articles in the autumn of 2016 dedicated to the murder at Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray (see here, here and here), Mediapart stated that the investigation highlighted no public scandals, did not unearth any individual failures by ministers or police chiefs and did not find any particular fault on the part of the intelligence services. It would be “excessive” to say that there had been a major failing, Mediapart argued. A year later and after six month persuading certain police officers to talk – even anonymously – and that judgement needs revising.

In fact there was an enormous failure. A French intelligence service had been perfectly placed to observe the preparations of an attack which ended up costing a priest's life and leaving one of his parishioners with severe injuries. Yet this service did not pass the information on and after the crime had been committed its hierarchy sought to post-date documents to hide its responsibility.

The scandal took place on the Île de la Cité, the island on the River Seine in Paris where the Direction du Renseignement de la Préfecture de police (DRPP), the intelligence department of the Paris police, is based. Among the staff are 123 employees who work in section 'T1', which is in charge of the fight against terrorism.

Not so long ago there were just 67 of them but the Charlie Hebdo massacre, the Jewish supermarket killings and the November 2015 Paris terror attacks led to more agents being recruited. They had to share computers and offices, with ten staff crammed into space that had previously been used by five, and there was nowhere to store their belongings and no air conditioning. “People are suffering from the heat, it's grubby, there are mice,” one former agent told Mediapart. Some new agents, however, were still thrilled to be involved. “We're going to hunt terrorists!” some noted on their Facebook pages.

The DRPP has 870 staff in total, all working at the time for “King René”, the nickname of the inspector general René Bailly who had been in charge of the service since June 2009. This all-powerful director of intelligence at the Paris police service had survived three prefects and six ministers of the interior in that time. And, unusually if not uniquely for an intelligence chief, up to the summer of 2016 he had not been at the centre of any controversies linked to the wave of terror attacks that France has suffered in recent years.

Bailly was certainly skilful at avoiding flak. On May 26th, 2016 he had addressed MPs who were ready to grill him as part of an investigation into the attacks in 2015. After a few opening probes from the president of the investigating commission, conservative MP Georges Fenech, Bailly replied: “The questions that you raise with me seem to be on a grand scale compared with the modest nature of this directorate.”

Later “King René” went on to explain that he had been put in his position to re-establish links between the DRPP and the “rest of the world”.

During his questioning Bailly had a dig at other agencies, regretting, for example, that his “colleagues at the DGSI” were mostly focused on “technology”. Questioned about the supposed exchange of information that existed with the prison authorities on radicalised prisoners, he said that in any relationship there should not just be “one way traffic”. He also claimed some credit for his organisation in the DGSI's dismantling of some radical networks in 2013.

In April 2012 René Bailly had placed in charge of his domestic intelligence team a divisional superintendent described variously in a book on the Paris police ('Bienvenue place Beauvau' published by Robert-Laffont, 2017) as “very close” and a “loyal lieutenant”. This deputy oversaw the T1 unit which was run by another officer, Richard Thery, whose influence went beyond his rank, as he was also number three in the police superintendents' association the SCPN.

Hierarchy on holiday

We will call him 'Paul'. He was a junior officer who had worked at the DRPP since before the recent wave of recruitment and was in the 'computer and trial' group, though the group no longer monitors criminal trials. He was one of five officers involved in computer surveillance. On Thursday July 21st July, using an alias, Paul was surfing social networks when he came across the 'Haqq-Wad-Dalil' channel. This was still five days before the murder of Father Hamel.

Getting access to the 118 photographs, three videos, 29 documents, 89 audio messages and 89 links published by the administrator of that channel was very simple. All you had to do was sign up to it. Site members could then pose any questions they wanted of the administrator on subjects such as fatwas legitimising martyr attacks by jihadists. Another cyber security expert says that '@Jayyed's' profile contained “numerous indicators”. Later a police report noted: “The tone of the communications by this channel's administrator … shed light on a jihadist profile which is moving in a very explicit way towards the Islamic State organisation”.

From his office Paul looked on as the site's administrator described how he preferred the “law of an eye for an eye in France rather than hijrah [editor's note, emigration] to Syria”, and recommended the creation of a “virtual” Islamic State province in France with an emir in charge who would allow “brothers” to help each other leave or to “prepare things here”.

During discussions '@Jayyed' gave more and more away about himself. He described in great detail his two attempts to go to Syria, how for his journey he had borrowed the identity card of an “unbeliever”, how just three weeks after being arrested in Germany he had managed to leave again, this time with another “brother”. He gave details on the fellow jihadist inmates he met in prison and explained how after his release he had to wear an electronic tag. The site administrator even invited his subscribers from the Rouen area to come to the lessons that he gave on Mondays, Tuesdays and Thursdays in a mosque at “Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray”.

All this information would have helped to have identified him. Could it even have been 'Paul', hidden behind one or more aliases, who asked the questions that elicited such information? Or was it he who was the site user who asked the administrator about his preference between emigrating and committing an attack in France? None of the sources Mediapart spoke to was able to answer these questions.

As for @Jayyed, he made no mystery of his intentions. Because of the difficulties in getting to Syria, it was preferable for him to act “here”, in other words, France. And Adel Kermiche had a very precise idea in mind which he set out in a audio message that lasted for seven minutes and 20 seconds. The target had to be churches, he said.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The teenager said that with a knife “one could create carnage by cutting off two or three heads”. A later police report on Father Hamel's murder said of Kermiche: “Seeming particularly keen on this target, he incited his subscribers to get hold of weapons to carry out this type of attack.”

During his monologue on the subject Kermiche said the importance of such an attack lay not in the number of deaths but rather the symbolism of the target. For him places of worship were ideal. “You go into a church where there's polytheism and you destroy everyone, I don't know! You do what has to be done and that's it!”

He concludes with some very explicit advice to aspiring jihadists. “People who are here at this time, I advise you to strike. There! I say it outright: strike!” Having listened to this worrying audio message Paul did what he had been taught to do and filled in a file.

The file in question is what is called a 'Gesterext' file, an acronym for 'Gestion du terrorisme et des extrémismes à potentialité violente', an intelligence file for managing dossiers involving terrorists and potentially violent extremists used by the DRPP. The DGSI equivalent is called 'Cristina'. A Gesterext file is classified as an official secret and is treated as a file affecting national “sovereignty” under a 1978 law on computers, files and individual freedoms.

According to a report by MPs Delphine Batho and Jacques-Alain Bénisti in 2009, these files are aimed at “preventing acts of terrorism” and for carrying out surveillance on individuals, groups and organisations who might be a threat to “national security”. These files were therefore a “tool” just for the use of the agents at the DRPP in carrying out their work. However, the MPs said, agents from the DGSI involved in relevant cases “could be made recipients of information contained in Gesterext”.

That was precisely the case here. As the person behind the 'Haqq-Wad-Dalil' online channel was based in Normandy, and in all likelihood in Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray, the jurisdiction over the case fell not to the DRPP in Paris but to the national agency the DGSI. That was why Paul filled in the Gesterext file and also wrote an accompanying unsigned report. The information was compiled to go in the DRPP's own archives but above all to be passed on to counterparts at the DGSI.

As Mediapart has previously stated, there is excessive compartmentalisation between the different French intelligence services. Officially the DRPP – part of the Paris police force – have a liaison officer at the DGSI HQ at Levallois-Perret in north-west Paris, and the DGSI has one at the police HQ on the Île de la Cité. This is to ensure that there are no more “holes in the racket” as former interior minister Bernard Cazeneuve put it. “The DGSI liaison officer has come by once to shake our hand but we don't really know what he does here,” a previously cited former DRPP agent told Mediapart.

Moreover, Paul and his colleagues are not allowed to telephone their counterpart at the DGSI. They have to pass on the unsigned report to be corrected and validated by four layers of hierarchy - the three superintendents and one of the two officers at the DRPP in charge of coordinating anti-terrorism activities – who must then decide what happens next. “They want to control everything that we produce but don't trust us, nor even each other. That creates a bottleneck, reports are kept waiting,” says a former agent at the T1 unit.

“The information remains trapped,” a third officer told Mediapart. “Because what one writes is classified as an official secret, there are too many checks, too many readings, too many chiefs who want to correct the reports, adding their two pennies worth, to give the impression they are adding value to it.”

The agent added: “They hold onto notes because a comma is wrongly placed....The emphasis is on satisfying the superior [officer], one forgets the operational nature of the report.”

In theory, two of T1's five superior officers are always on duty. But this episode occurred in the second half of July and four of the officers were on holiday. The fifth, a superintendent who had been tracking the movement of members of the Basque separatist group ETA, was snowed under with work. As a result, and as several sources have told Mediapart, Paul's notes were lost in the Gesterext file and his unsigned report was waiting for approval in the computer belonging to Richard Thery's deputy superintendent.

'State within a state'

This deputy-superintendent, the number three at the DRPP unit in charge of public security, is a former officer at the gendarme unit that tackles environmental and public health crimes the Office Central de Lutte Contre les Atteintes à l’Environnement et à la Santé Publique (OCLAESP). He is regarded by a superior officer to whom Mediapart spoke as an “honest and straight man”. On Monday July 25th, a day before the priest's murder, this officer returned from holiday.

It is not known if Paul's report was the only one in the shared 'Operational Coordinator' message system or whether it was full of a string of equally urgent requests and demands. It had certainly been a hectic time for intelligence and security forces. Ten days earlier the massacre at Nice had traumatised the country and police after the end of a Euro 2016 football tournament at which many had feared the worse but which had passed off peacefully. Nerves were frayed and bodies were tired. In any case, according to two different sources, the officer did not see the report from Paul, he did not pass it on to René Bailly and it was not therefore sent to the DGSI.

As the report highlighting the activities of 'Haqq-Wad-Dalil' languished unread in the DRPP superintendent's computer on July 25th, that channel's administrator was, at 2.45pm on that very same day, urging his followers to be ready to share forthcoming content that would be “exceptional” and “surprising”. '@Jayyed' asked his subscribers to dedicate their thoughts to him so that he could carry out his “plan”. A police officer who later analysed this comment on Telegram said: “The tone of his comments suggests that it is a farewell message.”

Two hours later Adel Kermiche published a photo on Snapchat (see below) which showed him in “camouflage uniform”, according to the expression used by one of his friends, and accompanied by an unknown man. It was later discovered that this man was the second attacker, Abdel Malik Petitjean. Immediately afterwards these two young men made their way to the front of the church at Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray, only to find the doors closed. They decided to postpone their grim plan until the following morning.

At 8.31pm on Tuesday July 26th, the administrator of Haqq-Wad-Dalil called on his Telegram channel subscribers to “download what's going to come and share it en masse!!!!”. After this Adel Kermiche left his family home, respecting one last time the terms of his court order which authorised him to leave his parents' house between 8.30am and 12.30pm on weekdays. It was 60 minutes before Father Hamel's murder.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The mass being celebrated by the 85-year-old priest was drawing to its close before a meagre congregation – three nuns and two parishioners aged 86 and 87 – when at around 9.25am a young man with a “gentle expression” and wearing a blue jacket entered into the church at Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray asking for information. One of the nuns, taking him for a student, asked him to come back after the service. A few minutes later he came back accompanied by a second young man. Carrying a backpack and a bag the two brandished a handgun and a knife and ordered the congregation to remain calm.

The two young men seized the frail 5 feet 2-inch tall priest and forced him to kneel at the altar. While one of the two men kept Jacques Hamel kneeling the other held out a mobile phone to one of the pensioners and forced him to film the scene. The priest was stabbed in the throat, with his executioner chanting words to the glory of the Islamic State in both French and Arabic. “Be gone, Satan!” cried the priest before collapsing.

The man with the knife now grabbed the parishioner who was filming the scene and having dragged him to the altar stabbed him four times in the throat and back. The elderly man fell and played dead. He later underwent two operations but was able to give a statement a few days later from his hospital bed. Meanwhile during the attack one of the nuns had been able to slip out of the church and raise the alarm.

An hour later and police launched their assault. The door to the vestry was broken down and the two terrorists rushed out shouting “Allah akbar”. One held a handgun, the other a black tube – the weapons were later shown to be fake. They fell, riddled with bullets. Abdel Malik Petitjean, dressed in military fatigues, was disfigured. The second youth, dressed in a traditional black Afghan-style qamis or tunic and a black woollen prayer had an electronic tag on his ankle. This was Adel Kermiche.

Detectives from the police's anti-terrorist division SDAT were put in charge of the subsequent investigation. They began piecing together the background to the murder. SDAT 44 – since the killing of two police officers at Magnanville west of Paris a month earlier police officers were kept anonymous during terrorist cases – looked to see what he could find “openly on the public internet”. He came across the Facebook account in Kermiche's name. Officer 44 noted that in the videos there was a scene in which two teenagers threw eggs at each other in a kitchen, that the account user based in Rouen was a fan of Bruce Lee, Harry Potter and The Simpsons, that he supported Barcelona and Paris-Saint-Germain and that he listened to the music of pop singer Rihanna.

In short, SDAT 44 was struggling for a lead.

Meanwhile on the Île de la Cité there was panic when it was discovered that the suspect whose file they had forgotten to pass on had just murdered a priest. It looked bad for them. Two months earlier the press had revealed how the number two at the DRPP, 'King René's' deputy, Nicolas de Leffe, had been demoted for misappropriating some of the 30,000 euros sent each year by the DGSI to pay the DRPP's terrorist case sources. And he was doing so to fund a project to restore a provincial château and turn it into a bed and breakfast venue. An investigation by the police watchdog body the Inspection Générale de la Police Nationale (IGPN) established the facts of the case, and the senior officer was temporarily suspended from the police service.

Even more importantly in the context of the Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray case, the very existence of the DRPP had been called into question three weeks earlier, on July 5th, 2016, by the report of that commission of inquiry into recent terrorist attacks to whom Bailly had given evidence. In its 14th recommendation the inquiry's rapporteur, the Socialist Party Member of Parliament Sébastien Pietrasanta, advised “sharing the duties” of the DRPP between the DGSI and a new regional intelligence service.

The interior minister at the time, Bernard Cazeneuve, was not particularly against the idea either. In a letter sent to MPs Sébastien Pietrasanta and the conservative MP Georges Fenech, the minister said that he had “taken note” of the inquiry's questions and said he was asking the intelligence watchdog, the Inspection des services de renseignement (ISR), to carry out an expert appraisal on the relationship between the Parisian intelligence service and the other specialist agencies.

There was thus a real threat that the powerful Police Prefecture in Paris – which is sometimes described as a 'state within a state' – could lose its intelligence service the DRPP. In such a context the revelation of its failure over the Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray murder could seal the DRPP's fate.

The intelligence service's attempted cover-up

On July 26th, 2016, the same day as the murder of Father Hamel, intelligence officer Paul was called in by his superiors. Under the supervision of a coordinator the cyber policeman over-wrote his Gesterext file and his report. According to several different sources he then rewrote the documents and post-dated them to that day, in an attempt to hide the DRPP's mistake.

However, the operation was done in a hurry and the changes made to the Gesterext file preserved the original date in the “properties” tab, which went back to July 21st. So Paul was called back in to put this right. He was also ordered to remove the search history on his search engine so that no one could discover when he had come across Kermiche's online channel on Telegram. “Yes our superiors did indeed try to remove the traces and they did it badly,” an agent said. “There was an attempt at back-pedalling but it didn't work as planned...”

At that very same moment the SDAT, who were investigating the murder, reported “information” that had come to them “this July 26th, 2016, at 2pm” which stated that “an unidentified young man, the administrator of a channel appearing on the message service Telegram called Haqq-Wad-Dalil, had broadcast there some radical messages in which he mentioned in particular attacks on churches”. The officer SDAT 12, who wrote a statement about the content of the channel, noticed with regret that simply clicking on the link leading to the channel made “all its content … accessible without any registration or co-option necessary”.

What was also frustrating was that the intelligence services had already been on the trail of Kermische's accomplice. On July 19th, 2016, Abdel-Malik Petitjean sent a video to Islamic State propagandist Rachid Kassim in Mosul in Iraq in which he openly threatened France with new attacks in response to bombings in Syria. The American secret services got hold of this video and handed it to their French counterparts. The video was broadcast nationally within the offices of the police service on July 22nd with the aim of identifying the author of the video.

This report form entitled “Menace against national territory”, whose existence was revealed by French broadcaster RTL and whose content was quoted by Le Monde, said: “The individual … seems to be ready to take part in an attack on national territory. He is apparently already here in France and could act alone or with other individuals. The date, target and the modus operandi of these actions are for the moment unknown. Investigations are currently under way with the aim of identifying and locating him.” This was four days before the priest's murder yet no one recognised Abdel Malik Petitjean from the video. Yet he was already the subject of a 'S' file, meaning he was seen as potentially a risk to national security. As Mediapart has already revealed, the intelligence officer in charge of monitoring this individual from his DGSI base in Savoie south-east France was on holiday at the time. Had the information from the American secret services and the information sat on by the DRPP been cross-checked, this could have identified the two young terrorists.

During this crucial period, on the night of 21st July, Abdel Malik Petitjean contacted Adel Kermiche via Telegram, but this time via private messages. The former asked the latter if he knew of techniques for carrying out actions and if he knew “determined brothers” who would carry out an action, as he was finding it hard to carry out an attack on his own with just a knife. Kermiche replied that he “wanted to strike as soon as possible” and that he “had plans”. He set out the horrific scenario: having “discreetly” checked the number of people... “I get moving and we enter the church.... take the chief (Priest). Make a video with a speech written in advance. Decapitate him and send the video. En masse, on Telegram.” In hindsight a phrase uttered by René Bailly to the commission of inquiry a month before the attack resonates with cruel irony: “To me it's interesting to remember that the terrorists always write in advance what they are going to do.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Bailly's own service then found itself entangled in the Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray case when it came across what one of the terrorists had written in advance – and did nothing with it. “That's true. The report remained held up over a weekend because some people were on holiday,” one DRPP agent told Mediapart. However, he repeatedly insisted: “But afterwards there were several layers of approval to go through before it could be communicated to other services. The administrative long-windedness is such that the information would never have arrived in time to save the priest.” The agent said he was not shocked by the subsequent “unfortunate cover-up” before adding: “What is a problem for us is the slowness in the sending of our information.”

When contacted by Mediapart the senior officer who had been in charge and who had been tracking ETA operatives said he did not want to discuss this issue and in any case was not supposed to talk in general as he was subject to rules on official secrets. Superintendent Richard Thery, who leads the T1 unit, told Mediapart that he had “no comment to make” on the issue because he was not aware of it. However, he knew that Mediapart had already contacted “several members” of his unit and criticised Mediapart for “putting people in this service in difficulty” by revealing the cover-up attempt which he said he was unaware of. The Paris Prefecture de Police said it had “no comment to make on claims from ill-intentioned sources”.

Messages were also left with René Bailly and the deputy in charge of the T1 unit and there was no response. Several sources have told Mediapart that this latter senior officer has been “wracked with guilt” since the church attack. Over and above individual responsibilities in the case, he has apparently been questioning the way the country's various institutions function.

There is a temptation to say that the DRPP's failure is the worst such scandal since the start of the wave of attacks that has hit France. But there have been other blunders too. Mediapart alone has highlighted a number of them. For example, we know that the most important and recent reports on the DGSI's surveillance of the Kouachi brothers Saïd and Chérif before the Charlie Hebdo massacre in January 2015 have still not been made public. We know, too, that the elite police special forces unit RAID led by Jean-Michel Fauvergue – before he became an MP for President Emmanuel Macron's ruling La République En Marche! party – sought to hide from the judicial authorities the proof of its failures in the assault on the hideout of the remaining members of the group who carried out the November attack in Paris in 2015. And it has emerged how the conservative mayor of Nice Christian Estrosi did everything he could to create a row with the Ministry of the Interior over the terrible lorry massacre in the city on July 14th, 2016 in a bid to hide the real truth: that the city's cameras on the Promenade des Anglais where the attack occurred had captured the eleven reconnaissance visits of the attacker without anyone from the city's police force reacting to it.

The overall picture shows that after each of the bloodiest and most shocking attacks in France over the last three years there had been an attempt by one state or regional security service to escape its own responsibility. All of them have sought to rewrite history going, in some cases, to the limits of legality.

Nonetheless the Saint-Étienne-du-Rouvray case crosses a line because of the attempt at falsification, confirmed by several witnesses, which followed it. It is something for which the DRPP has form.

The DRPP's resistance to judicial orders

The examining magistrates investigating the Paris attacks of January 2015 wrote to the minister of the interior asking for secrecy to be waived and for “all documents, reports and notes produced by the DGSI and other intelligence services under your authority on the surveillance (dates, type, content) of Saïd Kouachi, Chérif Kouachi and Amedy Coulibaly” before they carried out their crimes to be sent to them. The DGSI complied and 41 of its reports were declassified. A similar request was made during the investigation into the November 2016 Paris attacks and this time the DGSI handed over 84 reports to judges. The regional intelligence services, the Renseignements Territoriaux, who are not subject to official secrets rules, passed 41 documents to the judicial authorities. Another organisation, France's overseas intelligence agency the DGSE, the most secretive of the secret services, disclosed 45 of its documents.

It was only the DRPP who did not comply. This was not because the service had not been involved in keeping watch on the people involved in the different attacks. When speaking to the Parliamentary commission of inquiry its boss René Bailly explained that Saïd Kouachi and Islamic State terrorist Salim Benghalem were in the “top ten” of French people fighting in Islamist ranks in Iraq and Syria who had been placed under surveillance by his service in 2011. The surveillance on Saïd Kouachi resumed in February 2014 before being abandoned for good in June 2014 because, said Bailly, it had been established that “Saïd Kouachi was no longer in the Paris region but in Reims” to the north-east of the capital. So seven months before the Charlie Hebdo massacre the DRPP had carried out surveillance on one of the future attackers but nothing was passed to the investigating judges.

René Bailly also told the commission that in relation to the November 2016 attack in Paris they had been keeping surveillance on Samy Amimour, a radicalised train driver who was a member of a police shooting club. Here again none of the reports on the work carried out by the DRPP's intelligence service were handed over to the judges.

When contacted by Mediapart, the interior minister at the time, Bernard Cazeneuve, was categoric. “I had given a very clear instruction: that we declassify everything that we had. Afterwards, of course, we had to be bound by the recommendations of the Commission Consultative du Secret de la Défense Nationale,” he added, referring to the independent body which gives its opinion on whether sensitive documents should be declassified. He said he could not recall why a service would have contravened this directive.

Questioned at to why the DRPP was the only intelligence service not to hand over its reports in the different terrorist attack cases, the prosecution authorities in Paris told Mediapart that they had “no comment”.

Yet when giving evidence to the Parliamentary commission René Bailly had stated that the DRPP was “totally transparent with respect to the DGSI as to the activity it carries out and the information that it has … the DGSI has knowledge, daily and in real time, of all the information handled, written up and transmitted by the DRPP … I think in contrast that there is complete compartmentalisation concerning the activities of the DRPP in relation to the rest of the intelligence community.”

On April 17th, 2017, René Bailly invoked his right to take retirement. He was replaced by Françoise Bilancini, the first woman to head a French intelligence service. She came from the DGSI and was tasked, as her predecessor says he was too, with “re-establishing” the flow of information between the DRPP and the “rest of the world”.

On November 27th, 2017, the new director put an end to the mutual cooperation unit with the regional intelligence service the Renseignements Territoriaux, because of recurring disputes between the two. Questioned about this the Paris Police Prefecture said the move concerned a “superfluous” function and the aim was to avoid “duplication and multiple channels”.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter

A short version of this story was published on Friday January 5th, 2018; this full version was published on Sunday January 7th, 2018.