It was the most impressive comeback in the history of French football. When Russian oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev bought two-thirds of the shares in AS Monaco from the Riviera principality’s rulers in December 2011, the club was 18th in the French second division, Ligue 2, and in dire financial straits. Two and a half years later, the club had reached the top-flight Ligue 1, where it finished second at the end of the 2013-2014 season and as a result qualified for the Champions League.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

But behind the stunning on-field performance was a secret. Having made much of his estimated wealth of at least 6.8 billion dollars in potash production in Russia, Rybolovlev employed the same methods as his compatriot and fellow oligarch Roman Abramovich at Chelsea, and also Qatar at PSG.

Documents obtained by German news magazine Der Spiegel, gathered under the project Football Leaks, (see more on the source here) and analysed by Mediapart and its partners in the European media network European Investigative Collaborations, reveal that after taking control of AS Monaco, Rybolovlev pumped 326 million euros into the club over a period of two years in violation of the rules of European football’s administrative body, the Union of European Football Associations (UEFA).

Since 2010, UEFA has placed a ban on shareholders pouring unlimited amounts of funds into their club’s budget. The ban is part of a UEFA programme called Financial Fair Play, which is primarily aimed at preventing clubs from spending more than they earn and, as a result, becoming steeped in debt. It also works towards a partial levelling of the playing field between clubs of limited resources and those whose billionaire owners inject massive sums, notably on buying top players.

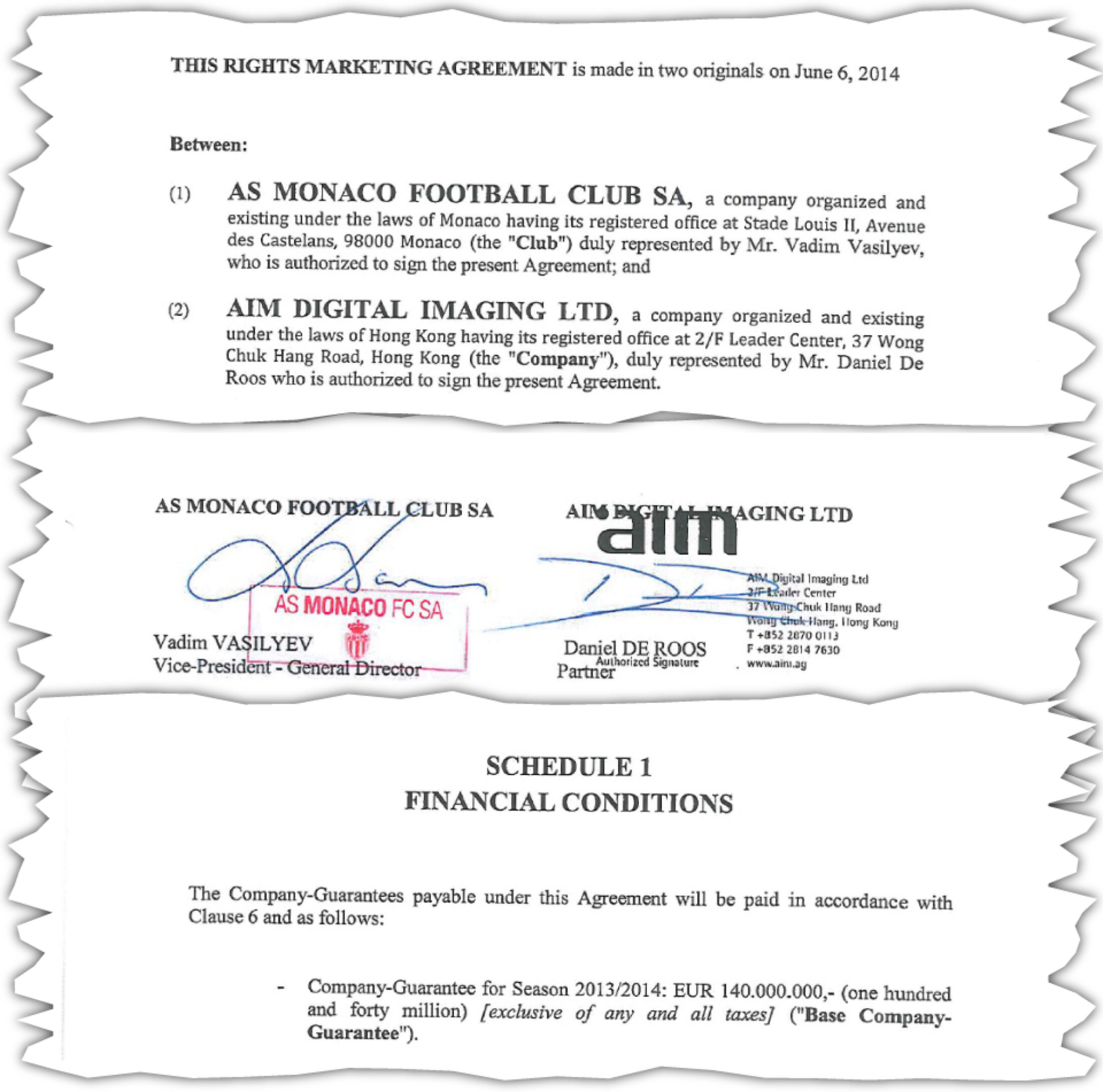

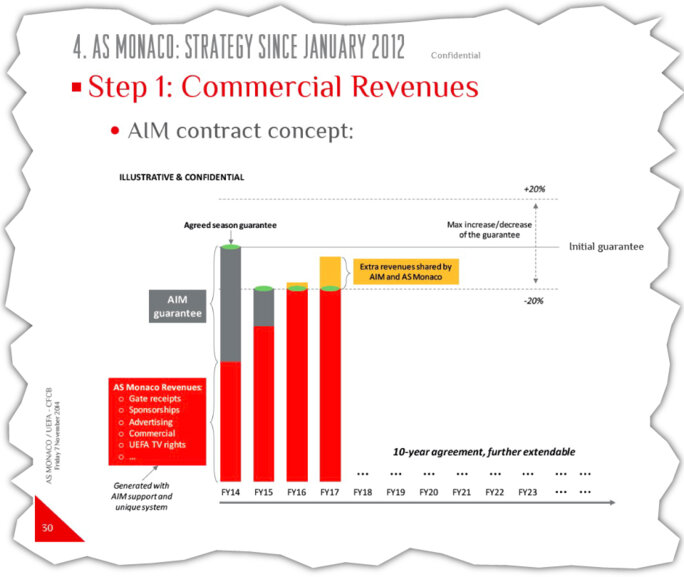

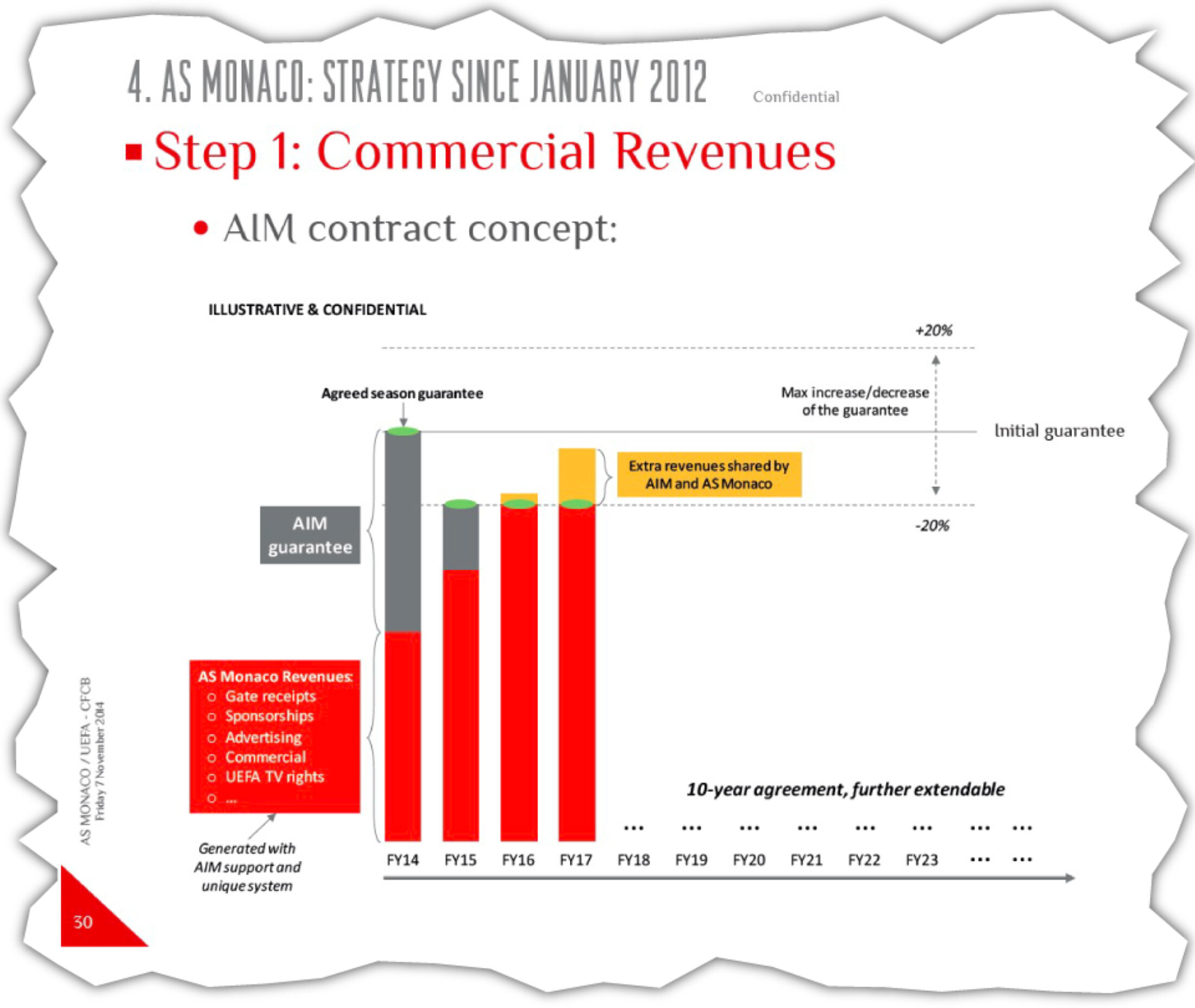

In June 2014, AS Monaco signed a deal with a sports marketing agency by which the club would receive 140 million euros per year. In reality, the plan was for the sum to be secretly provided by Rybolovlev, using an offshore arrangement that funnelled the funds via the British Virgin Islands and Hong Kong. Thus Rybolovlev’s funds would appear to come from a sponsorship deal, which would meet the requirements of UEFA’s financial fair play rules. But things did not quite go to plan.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In the end, the project collapsed after a disagreement between Rybolovlev and Bernard de Roos, the Dutch head of the Swiss-based sports marketing agency, AIM, at the heart of the deal. During the dispute, de Roos threatened to activate what he called a “neutron bomb” – namely, to reveal the scam to UEFA. To avoid the potentially massive fallout, AS Monaco concluded an amicable agreement with the agency.

While the club came close to going into liquidation, it escaped with a relatively minor penalty from UEFA despite the size of its deficit and the attempted fraud. UEFA, which at the time was presided by Michel Platini, with Gianni Infantino (now head of football’s worldwide governing body FIFA) as his secretary general, entered into an amicable agreement with the club which included a fine of just 2 million euros.

While the investigatory chamber of UEFA’s Club Financial Control Body (CFCB) had discovered a number of disturbing elements regarding AS Monaco’s financial affairs, it omitted from its findings any mention of information that compromised the club. Behind the scenes, AS Monaco had led an effective lobbying campaign with which it was able to approach key figures in the case. Following a dinner arranged at a Michelin-starred restaurant in Monaco, the head of UEFA’s financial fair play programme helped the club prepare for the hearings at UEFA’s investigatory chamber.

Bernard de Roos did not reply to Mediapart’s request for an interview. Also contacted by Mediapart, AS Monaco sent a written reply in which it did not deny the revelations in this report about the financial structure put in place around the AIM payments. In its statement in English, the club said its collaboration with the Swiss-based agency had been “made public” at the time, and was designed to “develop the Club's capacity” by “seeking sponsorship deals of the same calibre as those enjoyed by the biggest European clubs”, adding: “As the project proposed by this company turned out to be too ambitious and ultimately unachievable, AS Monaco made the decision to terminate the collaboration with the AIM agency while informing the sporting authorities of this breach of contract.”

After Rybolovlev took control of AS Monaco he invested 326 million euros in the club, half of which was spent in the summer of 2013 on building a top team of players for its return to Ligue 1. With the help of one of the world’s most prominent player agents, Jorge Mendes, the club recruited four international star footballers: these were Portuguese midfielder Joao Moutinho and his compatriot and centre back Ricardo Carvalho, and the Colombians Radamel Falcao, a striker, and attacking midfielder James Rodriguez.

In May 2014, AS Monaco finished the season in second position in Ligue 1, which qualified it to enter the prestigious European Champions League. It also meant it was subject to the regulations of financial fair play, causing the club to sell off or loan out most of its top players, including James Rodriguez who went to Real Madrid for 75 million euros (plus add-ons of 15 million euros). Dmitry Rybolovlev radically changed his tactics; instead injecting funds, the club was to finance itself through the sale of its players.

The method would later prove to be an enormous success, with the sale, season after season, of prodigies like, latterly, Kylian Mbappé (sold to PSG for 180 million euros), but also Thomas Lemar (sold for 70 million euros) and Benjamin Mendy (57 million euros). But in the process of selling off so many talented players the team’s performances have suffered, culminating in the sacking last month of its Portuguese coach Leonardo Jardim, who is replaced by former Arsenal and Barcelona star striker Thierry Henry, one of the France squad which won the World Cup in 1998.

But back in the summer of 2014, Dmitry Rybolovlev was uncertain whether this strategy of offloading players, decided under the pressure of meeting UEFA financial fair play rules, would pay off. Over the previous three seasons, AS Monaco ran up losses totalling 170 million euros, which is four times more than the ceiling of 45 million euros allowed by UEFA. As a result, it ran the risk of being excluded from the Champions League, regarded as the ultimate, most damaging disciplinary measure.

In 2013, Rybolovlev told the club’s board that in order to respect the financial fair play rules, “We will have to find sponsors to increase revenues and replace the contributions from the majority shareholder”. But the problem with that plan was that, against a backdrop of Monaco’s tiny population (just more than 35,000 of which only 9,000 are Monacan nationals), the club’s 18,500-capacity Louis II stadium was often far from full of spectators, and brand sponsors showed little interest. For the 2013-2014 season, ticket sales and sponsorship deals totalled just 14.4 million euros – a relative pittance for a club whose yearly budget then amounted to 125 million euros.

The inspection of accounts by the investigatory chamber of UEFA’s Club Financial Control Body (CFCB), a supposedly independent entity created by UEFA to police compliance of its financial fair play rules, were to begin in July 2014. But since January that year, AS Monaco began an intense lobbying campaign. Behind this was the club’s Russian vice-president Vadim Vasilyev and his special advisor Filips Dhondt, a Belgian who was well-connected in Monaco society and who helped with Rybolovlev’s purchase of the club. The aim of the campaign, Dhondt wrote to Vasilyev, was to find “a political solution”.

They were keen to meet two key figures. One was Jean-Luc Dehaene, president of the UEFA investigatory chamber, and who would be in charge of the investigation into AS Monaco, while the other was Andrea Traverso, head of the financial fair play programme at UEFA, and who was then directly answerable to Michel Platini and Gianni Infantino. Dehaene and Traverso were apparently so busy that they suggested a meeting at Nice airport, between flights. But Vadim Vasilyev invited the pair to “spend some time in Monaco together”. Dhondt suggested in a written note that, “a dinner in the evening will result in a different/better relationship”. The initially planned meeting was cancelled.

When UEFA's FFP chief was wined and dined in Monaco

On March 13th 2014, Dmitry Rybolovlev obtained a meeting at UEFA headquarters in Nyon, Switzerland, with its president Michel Platini and secretary general Gianni Infantino. Rybolovlev’s assistant informed him that Andrea Traverso “will also be available”. The Russian was to take the opportunity after the meeting of flying off by helicopter to his chalet at the Swiss Alpine resort of Gstaad.

AS Monaco’s marketing director wrote to Rybolovlev to brief him ahead of the meeting in Nyon, noting that the objective was to, “Build a closer personal relationship with UEFA President Michel Platini, [who is] the big promoter” of the financial fair play rules. He proposed that Rybolovlev should detail the club’s projects and “obviously not even give the slightest indication” that AS Monaco had violated the rules. He added that the Russian might “only if appropriate and to show that our president is well informed”, mention to Platini that the UEFA president’s son is employed by the Qatari owner of French club Paris Saint-Germain (PSG), which was “obviously close to a conflict of interest”. Questioned by the EIC, AS Monaco said that Rybolovlev had not followed the “inappropriate” advice.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

But lobbying on its own was not enough, and financing had to be found. In May 2014, Rybolovlev and his team came up with the idea of establishing a false marketing deal that would be secretly funded by Rybolovlev and which would funnel a massive 1.4 billion euros into AS Monaco.

The club needed to find a credible figure with whom to conclude the marketing deal, and found one in Dutchman Bernard de Roos. The former managing director of the Netherlands Olympic Committee, he joined a Swiss sports marketing agency called T.E.A.M., where he was involved in advising UEFA and played a central role in creating the concept of what is now the Champions League.

He later created his own agency, AIM Sport Marketing, based in Lucerne in central Switzerland, and pulled off a major coup in securing on behalf of a cable operator the TV rights to the 2006-2007 season of the top German football division, the Bundesliga, for a then-record 800 million euros.

In June 2014, AS Monaco drew up a contract with AIM (see document immediately below) under which the agency was to be given management of the sponsorship and marketing of the club, with the aim of boosting its revenues. Four AIM staff were hired by the club to lead the project (including AIM’s newly arrived marketing director Henri van der Aat), and the club was to rent from the agency, at a cost of 350,000 euros per year, state-of-the-art advertising boards for its Louis II stadium.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

AIM was to ensure the club received annual revenues of 140 million euros for a period of ten years. It represented an extraordinary sum – higher than the club’s then annual spending of 125 million euros, but also five times more than the value of the largest sponsorship deals secured by Real Madrid or FC Barcelona. AS Monaco would each year count its income (excluding those from French TV rights), including ticket sales, sponsors, and Champions League earnings, and if the total was inferior to 140 million euros, AIM would have to pay the difference.

But at the time, ticket sales and sponsorship deals brought the club a yearly total of just 14.4 million euros – which would leave an enormous shortfall of 125.6 million euros for AIM to pick up. “The project does not make sense economically,” wrote Tetiana Bersheda, lawyer for Rybolovlev and a member of the AS Monaco board, in an email addressed to Vadim Vasilyev and other club executives on May 12th. She warned of “potential sanctions if this scheme is disclosed” to UEFA.

The contract was all the more absurd in that it was retroactive, making AIM responsible for the balance from the 2013-2014 season which was on the point of ending. This was officially presented as being because the cooperation began on an informal basis one year earlier. Tetiana Bersheda contacted Rybolovlev’s ’family office’ Rigmora. “Do you make this contract retroactive? It is difficult to say [that it was] concluded orally in the past,” she wrote. “Please confirm.” To which one of Rybolovlev’s staff replied: “Yes.”

Another unusual element was that the contract was not signed with AIM in Switzerland but with a company registered in Hong Kong, called AIM Digital Imaging and which was personally controlled by Bernard de Roos. Referring to Rybolovlev’s acrimonious divorce at the time from his wife Elena, whose petition was filed in Switzerland, Tetiana Bersheda warned that the country where the company is registered “may NOT be Switzerland because of the risks related to the divorce”.

Shortly before, in a May 2014 ruling that was overturned on appeal one year later, Elena Rybolovlev obtained from a Geneva court a divorce settlement that gave her half of her husband’s wealth. This included assets in Cyprus-based trusts, which Rybolovlev had pretended he did not control, and which, under the plan, were to be used to finance via AIM a football club – AS Monaco – which, it was widely known, belonged to Dmitry Rybolovlev. Hong Kong was a more discreet choice.

Finally, the contract was antedated. Although it was given the date of June 6th, it was in fact signed between June 16th and June 20th, and just in time for the inclusion of the money from AIM into the club’s accounts that closed on June 30th and which, once completed, were sent off to UEFA. As a result, the club posted a profit of 11 million euros instead of losses of 116 million euros.

The deal was so unusual that it was decided that more lobbying was needed, and a UEFA pre-season get-together held every year in Monaco, and that year on August 26th and 27th, provided a timely venue. The event included conferences, cocktails, a barbeque and friendly football match.

Andrea Traverso, head of UEFA’s financial fair play programme, on the sidelines of the UEFA gathering in Monaco was invited by AS Monaco to dinner at the Michelin-starred restaurant of the late French chef Joël Robuchon, at the Hôtel Metropole in Monaco, for an “informal” discussion with Vadim Vasilyev and Bernard de Roos.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

The move was apparently successful. On October 27th, Andrea Traverso travelled to Monaco to secretly help the club to prepare for its hearing before the UEFA investigatory chamber which was leading the probe into AS Monaco. Dhondt wrote to Vasilyev: “No documents will be handed over […] Receive his comments, considerations and advice.”

UEFA’s investigatory chamber had opened an investigation into the AIM contract. The problem for AS Monaco was that the first payment of 9 million euros, which had been due to be made on October 3rd, had not arrived.

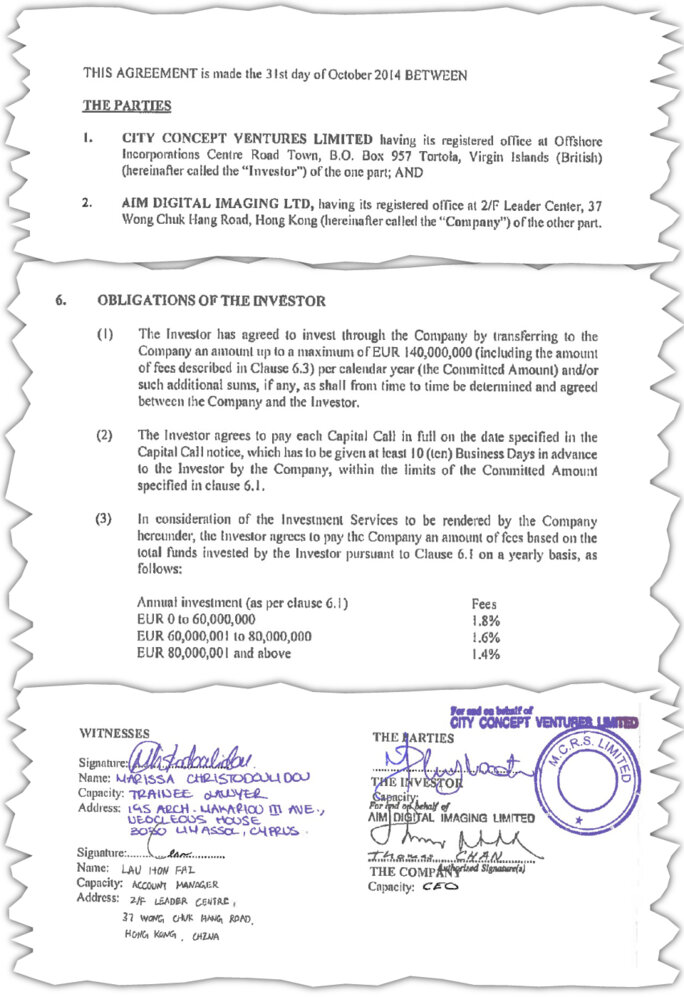

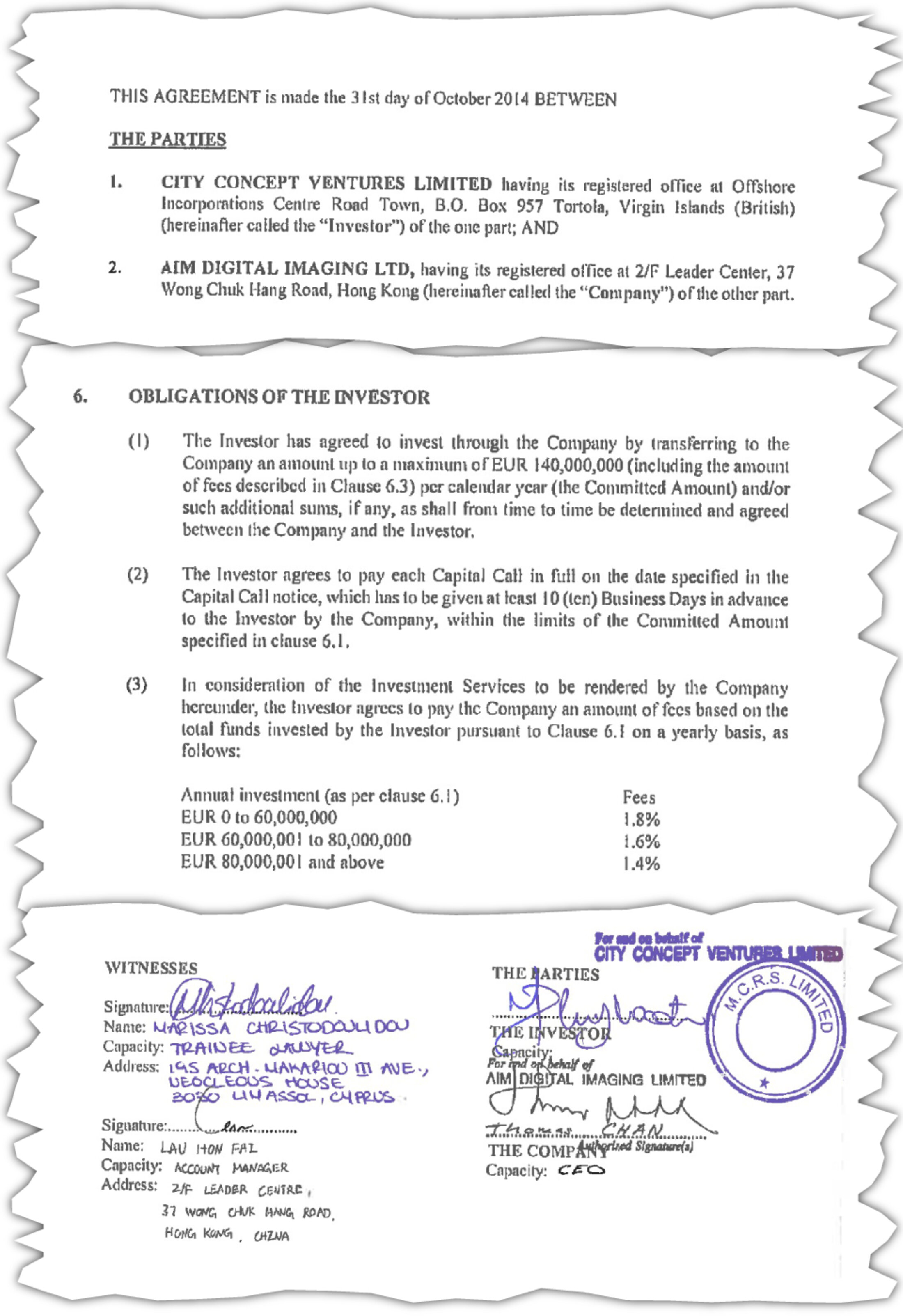

The reason was quite simply that Bernard de Roos did not have the money. The last stage in the offshore set-up behind the deal was only completed on October 31st, with a highly confidential “investment agreement” (see document immediately below). Under this, a shell company registered in the British Virgin Islands, City Concept Ventures (CCV), agreed “to invest” in AIM Digital Imaging 140 million euros per year over a period of ten years. This was exactly the amount that the company was to pay AS Monaco. The agreement also set out that CCV would pay 2.2 million euros per year to Bernard de Roos’ agency, the cost of his participation in the scheme.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

CCV was a disguise for Dmitry Rybolovlev. The contract details that CCV is managed by a law firm called Neocleous, which also manages the oligarch’s trusts in Cyprus. Several messages in email correspondence within AS Monaco confirmed that the contract was an “agreement between AIM and Rigmora”, the latter being the Russian billionaire’s family office.

The contract suddenly unblocked the situation, and on November 3rd Bernard de Roos contacted Vadim Vasilyev asking him to send “today the bank account details of AS Monaco in preparation for the transactions”.

'Nuclear bomb disarmed', rejoices Monaco's Swiss lawyer

On November 7th, the club officials travelled to the hearing before UEFA’s investigatory chamber. The AS Monaco representatives had no hesitation in lying about its new partnership agreement, claiming that half of the 140 million euros per year guaranteed by AIM was made up of real takings (see document immediately below). In fact, they accounted for less than 10% of the sum.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

But three days later a major problem arose. De Roos wrote to Vasilyev to say that he would not pay any money if AS Monaco did not agree to revise the contract. Officially, de Roos’ complaint was about the club’s sale during the summer of its best players which, he wrote, had “reduced the AS Monaco FC’s marketing and brand value and therefore significantly complicated the performance of AIM’s obligations”. He also accused the club of lying about the amount of its revenues from sponsorship deals.

The EIC investigation has learnt of another possible reason for the problem, which is that de Roos did not receive the 140 million euros in question via the British Virgin Islands. According to a source close to the club, this was because Rybolovelv and Monaco’s reigning monarch Prince Albert had a falling out over business issues involving the principality that had nothing to do with the club. According to the source, Rybolovelv was so furious that he decided to take revenge on the prince by putting an end to any further funding of AS Monaco.

Whatever the truth of that, documents obtained from Football Leaks confirm that Rybolovlev stopped funding of the club, which was already struggling because of AIM’s pull-out. Unless there was a fresh injection of funds, AS Monaco would be in voluntary liquidation within months.

The club studied the possibility of borrowing money against the guarantee of payments due to be paid to the club by UEFA at the end of the season for its participation in the Champions League. The club’s deputy director general wrote to Vasilyev to warn that given, officially, the club’s finances were “very positive”, the move for such loans should remain discreet “so as not to attract suspicions from UEFA”.

In the end, the club decided to secure loans using the guarantees of the two instalments of 25 million euros that Real Madrid was to make in 2015 and 2016 for its purchase of James Rodriguez. But Australian banking services group Macquarie had its own doubts about the AIM contract, and refused to lend any sum until de Roos’ agency had begun to make payments.

The club was left with no further choice. The funds from AIM would not be forthcoming, and the missing 125 million euros were compensated for by a write-off of a part of the debt owed by the club to its majority shareholder Dmitri Rybolovlev.

On November 26th, the club’s deputy director general Nicolas Holveck sent Vadim Vasilyev an advisory note on how to deal with the regulatory bodies. To the French watchdog over financial practice in football, the DNCG, AS Monaco would claim that the advance sums received on the Real Madrid payments for James Rodriguez, plus a cash injection of 6 million euros, would be sufficient to avoid bankruptcy. “That should be sufficient so that the DNCG doesn’t ask for new documents,” wrote Holveck.

On December 8th, Vasilyev and his advisor Filips Dhondt travelled to UEFA headquarters in Switzerland. Surprisingly, their appointment was not with the “independent” investigatory chamber which normally was the only body with authority to deal with the case. Instead, the club’s representatives had succeeded in going straight to Andrea Traverso, head of UEFA’s financial fair play programme, and who had previously been invited to dinner in Monaco. The club argued that the problem with AIM was linked to the sales of players that summer, and delays in a renovation of the AS Monaco stadium, but insisted that discussions were ongoing. In short, the club was suggesting that the contract could yet be saved.

Enlargement : Illustration 9

But the investigatory chamber continued with its probe, and commissioned accounting agency Deloitte to look at the club’s accounts, which it began doing in late January 2015. Deloitte subsequently produced a damning report pointing to the anomalies in the deal with AIM, including its retroactive clause. But apart from the contract, the club refused to hand over any “further documentation” and provided “no element indicating that AIM would honour” its payments.

Despite that, in its accounting previsions, AS Monaco indicated that AIM would pay it 49 million euros for the 2014-2015 season. The club had also incorrectly depreciated the 125 million euros concerning the previous season in order that it did not alter the financial fair play calculations. After Deloitte had underlined the problems of these two issues, the club immediately agreed to correct the situation. In all, the club had sent UEFA three different versions of its accounts.

Despite the suspicions of the auditors, no additional investigation was carried out and Bernard de Roos was not even called for questioning. In the concluding report by the chamber’s president, Umberto Lago, there was no mention of the difficulties between the club and AIM. Even more puzzling was that only the third and last version of the club’s accounts featured in the case file.

The final report did however conclude that the club had run up a deficit of 167 million euros over two years, which was more than three times the authorised limit. That meant that AS Monaco were in danger of being excluded from the Champions League, a measure meted out to other clubs (Malaga and Red Star Belgrade) for fraud concerning much smaller sums.

On March 13th 2015, the investigatory chamber decided to let AS Monaco off the hook with a particularly lenient amicable agreement, on the basis that the club had pledged to end the system of subsidies and introduce a new economic model based on the sale of players. Under the amicable agreement, the club was fined 2 million euros (whereas PSG had been fined 20 million euros) and a limit was placed on the number of players it could sell, and their price, for a period of one year.

That same evening, the club’s friend at UEFA, Andrea Traverso, head of the financial fair play programme, called Filips Dhondt to announce the good news, describing the agreement as being, “a very favourable settlement agreement, compared to what I see what happens with other clubs. Far, far away from PSG last year”.

Meanwhile, the dispute with AIM was threatening to upset everything. In revenge for Bernard de Roos’ refusal to honour the contract, AS Monaco fired the marketing director it had hired from AIM, and stopped paying the wages of the other three people it had recruited from AIM. The club also refused to pay the cost of the advertising boards erected at the Stade Louis II. De Roos demanded that AS Monaco pay up an outstanding total of 554,000 euros, while the club demanded that AIM pay up the 125 million euros agreed in the contract and took the dispute to an arbitration court. By then, de Roos and the club’s management were communicating via their lawyers.

On April 22nd 2015, AS Monaco were playing at home against Italian side Juventus in the quarter finals of the Champions League, when Bernard de Roos took the opportunity to tell Filips Dhondt, special advisor to Vadim Vasilyev, that he had “received two letters from UEFA” which he did “not intend to answer yet”, adding: “If no discussion or negotiation will come up soon, I will throw a neutron bomb […] They must stop playing this power game. I will be reasonable. Please bring this message to Vadim.”

The threat came at the worst moment for the club, for the next day UEFA sent it the final version of the amicable agreement, and nothing more was required other than to sign it. But if de Roos was to tell the UEFA investigators that AS Monaco’s scheme with AIM was created in order to disguise Rybolovlev’s secret funding of the club, the amicable agreement with UEFA would be scuppered.

However, the amicable agreement was finally signed on May 4th 2015. “This is great news and means that the ‘nuclear bomb’ referred to by AIM has been disarmed,” rejoiced AS Monaco’s Swiss lawyer. For AS Monaco had decided to give way on everything: on July 15th 2015 it withdrew its complaint against AIM, abandoning the 125 million euros it had been seeking, and handed AIM 500,000 euros for unpaid invoices. The secret was kept for then, and without the Football Leaks documents would never have been revealed.

AS Monaco had come within inches of disaster. But the club also gained a good relationship with Andrea Traverso, head of UEFA’s financial fair play programme, who had helped the club prepare for the hearings. On June 10th 2015 he agreed to pass on to Filips Dhont some details about the reforms to the financial fair play rules that were then under discussion at UEFA’s executive committee.

Traverso had apparently developed a taste for Joël Robuchon’s Michelin-starred restaurant at the Hôtel Metropole in Monaco. In mid-August 2015, three months after the end of the UEFA of AS Monaco, he insisted on having lunch with Vadim Vasilyev to discuss the “strategy” of the club towards financial fair play, on the sidelines of an annual UEFA meeting he would be attending in the principality two weeks later. Vasilyev of course accepted the proposition.

Contacted by the EIC, Andrea Traverso and the members of the investigating chamber declined to answer our questions. Michel Platini and Gianni Infantino, respectively president and pecretary general of UEFA at the time of the events detailed in this investigation, also declined to comment.

UEFA offered only a written response to the EIC, in the form of a statement about the rules of its financial fair play programme which it said was "there to assist clubs to become financially sustainable and to live within their means and only to sanction them as a last resort”. UEFA added that it was quite normal to propose amicable settlements to clubs that agree to implement a plan destined to restore financial compliance in the future.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

* Correction November 5th: the wealth of Dmitry Rybolovlev is estimated by Forbes magazine at 6.8 billion dollars, and not 6.8 billion euros as originally indicated.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

----------------------------------------------------------------------