The elections for control of the councils of France’s 13 new ‘super’ regions are the first since they were created, in a reform finalised earlier this year, from the previous 22. Since the last regional elections in 2010, 21 had until now been in the hands of the Socialist Party.

So next Sunday evening, when the results of second and final round of the current regional elections will be announced, Nicolas Sarkozy will put on a show of having triumphed, presenting the few regions won by the conservative opposition he leads like a victorious trophy.

But the maths of the results cannot mask the strategic failure of the former French president, as indeed is revealed by the results of last Sunday’s first-round vote. Sarkozy is head of the main conservative opposition party, Les Républicains (LR). As such, and almost mechanically so, he should have emerged on Sunday evening as the principal beneficiary of the vast movement rejecting the ruling socialist government. That is what happens in every civilised democracy, when a rejection of the political powers in place results in the landslide victory of the main opposition party.

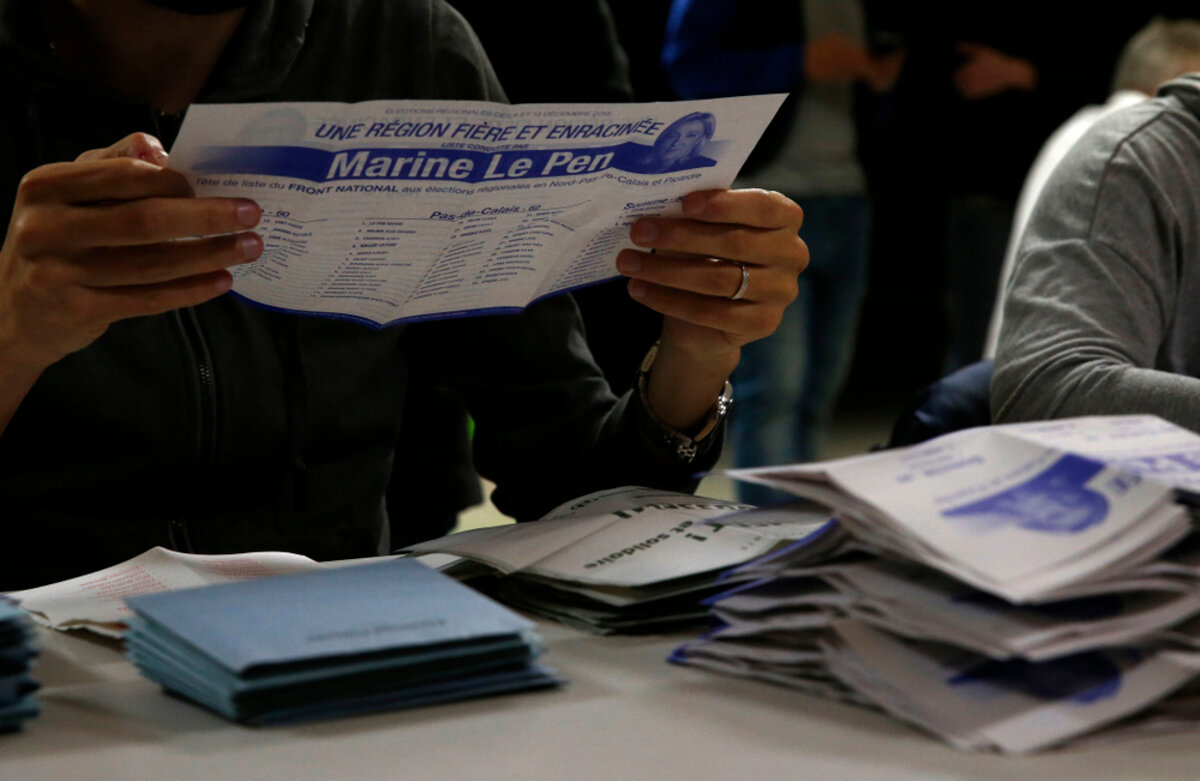

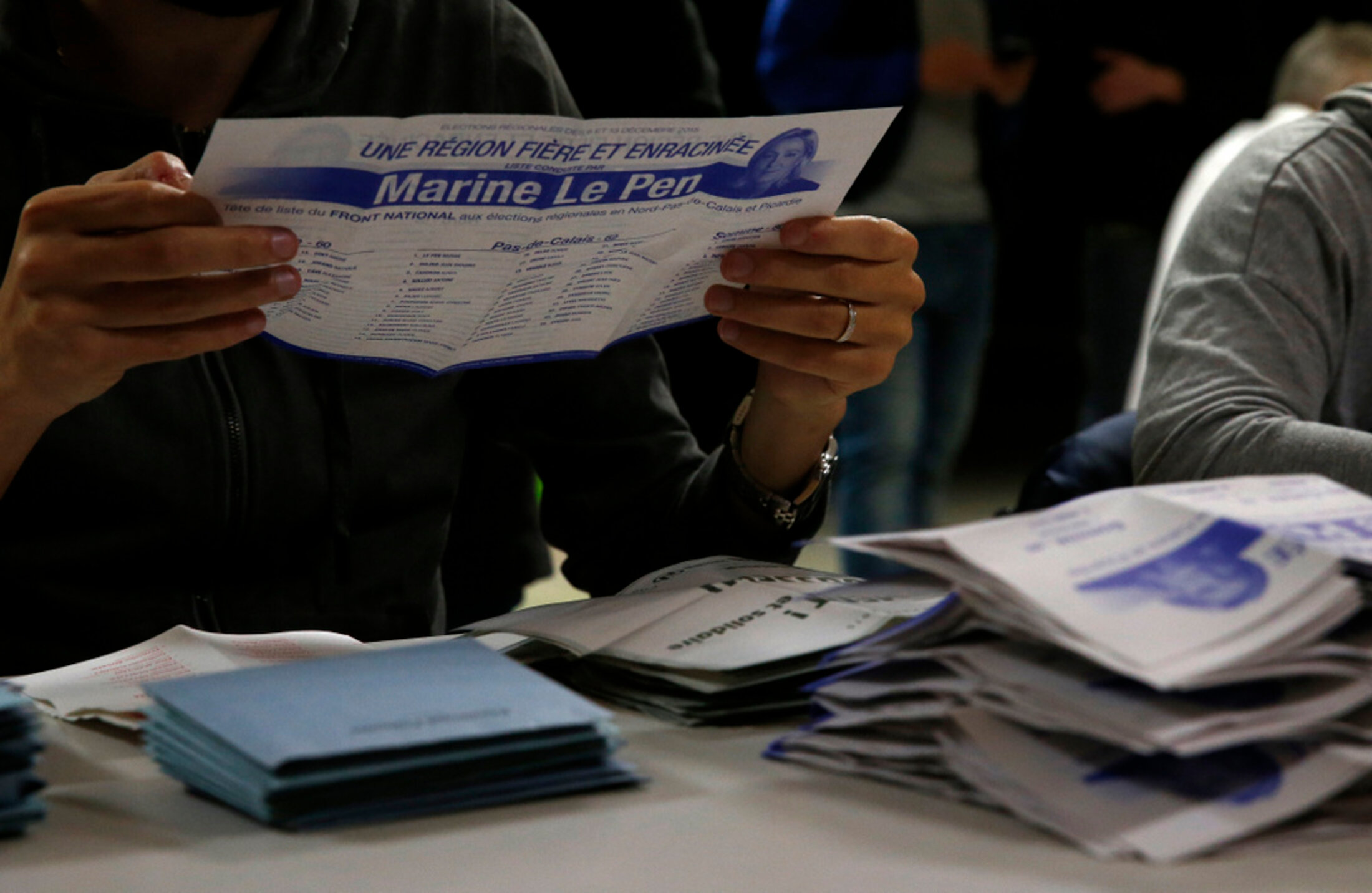

But nothing like that happened. Quite the opposite, in fact. The former UMP party, re-named by Sarkozy earlier this year as Les Républicains (Sarkozy was elected UMP leader in November last year), has suffered a resounding defeat. Of the 13 new regions, the far-right Front National candidates took the lead in six, Sarkozy’s LR was first-placed in four, and the Socialist Party and its centre-left allies came first in three.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In terms of the percentage share of votes cast, the LR did no better. While the Front National broke the watershed 40% share in several regions, the self-proclaimed “major party of the Right” just managed to garner around 27% (see the full results here). The abstention rate, at just under 50%, had a significant effect on the score obtained by the mainstream Right, just as it did also for the parties of the Left.

But worse still, the results obtained by Sarkozy’s re-named party are well below those it obtained, when it was still called the UMP, in the last regional elections in 2010. At the time, Sarkozy, then president, was a figure who crystallised opposition. During the first round of the 2010 regional elections, the UMP obtained, on its own, 26% of all votes cast nationwide. When the votes that went to its centre-right ally the UDI are added to the count, the then-ruling mainstream Right obtained 30% of the nationwide vote, while the Front National drew 11%.

The lists of candidates fielded across the regions by the LR party on Sunday included representatives of the UDI party (Sarkozy earlier having made a point of claiming to have built unity among the “family” of the Right). But their alliance scored 3% less than it did in 2010.

The damning fact is that even united, the mainstream Right obtained significantly less than five years ago, while the Front National has succeeded in tripling its score. The logical conclusion to such a defeat, as would have been decided in other European countries, is that the opposition party leader should be replaced. By winning the first round of the regional elections, the far-right has above all signed the LR’ president’s letter of dismissal. For the Le Pen family, this represents a grand revenge for the results of the first round of the presidential elections in 2007, when Sarkozy (who went on to win the second round against socialist candidate Ségolène Royal) had managed to attract the Front National electorate en masse.

Almost ten years later, the now former president sees himself presiding over a Right that has been reduced to rubble. Elected in November 2014 as LR leader by a small hardcore of party militants, he has achieved nothing else after one year in charge. Internal feudal wars in the party continue, while the prospect of primary elections next year to decide the party’s candidate for the presidential elections due in 2017 – in which Sarkozy faces rivals from LR bigwigs - distils a slow poison. Meanwhile, divergent strategies continue amid the absence of any project that would federate the electorate of the mainstream Right, including the centre-right.

As of last Sunday evening, these same divisions immediately resurfaced in public. Nicolas Sarkozy was the first of his party to comment the results, appearing on television at 8.30 p.m. with a confusing presentation, holding out his hand to the far-right electorate while above all calling on those who abstained to be present at the urns next Sunday- a typical refrain from defeated leaders. There was no calling into question strategy that led to defeat.

Since then-president Sarkozy’s speech in Grenoble in 2010, and especially since his (unsuccessful) campaign for re-election in 2012, entirely built on the themes espoused by the far-right, he has never changed tack. By employing the same language as the Front National, adopting its obsessions, its propositions and its priorities, he believed the conservatives would bring back to the fold its departed electorate. On Sunday, Sarkozy was given a giant demonstration that the opposite is true.

Two of his former ministers, both shining stars of the Sarkozy regime - Christian Estrosi and Xavier Bertrand - were simply crushed by the Front National in their respective regions of Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (see more here) and the Nord-Pas-de-Calais-Picardie; in Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (PACA), first-placed Marion Maréchal-Le Pen held a lead of more than 15% over Estrosi, as did also her aunt and party leader lead Marine Le Pen over Bertrand in the Nord-Pas-de-Calais-Picardie. In the PACA region, where the rise of the Front National was no overnight sensation, Estrosi, who is both a Member of Parliament and mayor of the Riviera city of Nice, and who notably once denounced the existence of a “fifth column of Islamo-fascists”, plainly flopped in his grotesque recent attempt to offer his hand to the electorate of the Left and Centre. In voting in three of the four départements (counties) that make up the region he came in second position, in a few cases third, (the exception being his fiefdom of the Alpes-Maritimes département, centred around Nice, where he inched into first place with a 37.91% share of the vote against the Front National’s 37.9%).

Sarkozy's rivals will be handed ammunition on a plate

Just as is the case for Xavier Bertrand, Estrosi will nevertheless benefit from the decision by the third-placed Socialist Party to withdraw from the race in his region in order to favour the chances, in a transfer of votes, for the best-placed mainstream party in face of the Front National, as announced Sunday evening by Socialist Party leader Jean-Christophe Cambadélis. But given the political pedigree of the two men, both of them products of the hardline Right, and given the gap between them and their Front National rivals, their prospects of winning next Sunday are virtually non-existent.

Which is why the LR party is not exactly overjoyed by the decision of the socialists to pull their candidates wherever a mainstream party is better placed to counter a victory by the Front National. Questioned last week by Mediapart, and after the Socialist Party had called on the LR to join it in such so-called “republican fronts” (which Sarkozy has dismissed), a source close to Sarkozy, whose name is withheld, commented that the tactic was “just an idea by the Socialist Party to bug us”. He added: “You see, even with a withdrawal and [a transfer of] votes from the Left, Xavier Bertrand is not capable of winning against the front National.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Nicolas Sarkozy has multiplied his efforts to support the party’s candidates in media interviews and campaigning on the ground, but to no avail. Today, the brand ‘Sarko’ can no longer even fire dislike. It prompts indifference. The notion of a “Right liberated of its complexes” has failed to draw support from an electorate that prefers the original version rather than the copied one. The one exception is in the central- southeast Auvergne-Rhône-Alpes region. There, LR lead candidate Laurent Wauquiez came first on Sunday, with a total 31.73% share of the vote, ahead of his Front National rival Christophe Boudot who drew 25.52%.

Apart from LR lead candidate for the Greater Paris Region (Ile-de-France), Valérie Pécresse, two other LR-UDI candidates also succeeded in taking a majority share of the vote on Sunday. These were the centre-right candidate Hervé Morin in Normandy and Bruno Retailleau in the west-central Pays de la Loire region, both of who are notably more moderate right-wingers than Wauquiez. Meanwhile, two of their similarly moderate centre-right colleagues, Philippe Vigier standing in the Centre-Val de Loire region, and François Sauvadet in the centre-east Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region, came behind the Front National, although both had been tipped as favourites up until just a few weeks ago.

The story is the same in the north-east Alsace-Champagne-Ardennes-Lorraine region, where the outgoing LR president of the regional council, Philippe Richert – who had lobbied for the eviction from the party of former Sarkozy minister Nadine Morano after her comments that France “is a country of white race” – came in on Sunday behind the Front National candidate. Richert drew a 25.83% share of the vote, against 36.06% for the Front’s Florian Philippot. Yet in the 2014 council elections for the département of the region, the mainstream Right had attracted more than 40% of the vote.

As for the Languedoc-Roussillon-Midi-Pyrénées region in southern France, the result lived up to the despairing forecast of the LR leadership. The party candidate, Dominique Reynié, a former director of centre-right thinktank Fondapol, and who is loathed by Sarkozy, had difficulty in reaching third position on Sunday.

These different profiles, as diverse as they are, ranging from the hardline Right to the centre-right, reflect what has become of the opposition party: a bear garden where only failure is the shared commodity.

In an attempt to avoid the Right from definitively disappearing between the Socialist Party and the Front National, Sarkozy on Sunday restated the principle of “neither withdrawal nor fusion” (the latter referring to the other socialist proposal of integrating joint lists of candidates to beat the far-right in the second round). This was officially adopted by the party’s executive committee on Monday. But that will not suffice.

Unless it quite simply resigns itself to observing the creation of a new political scene which will see a two-horse race for the presidency in 2017 between François Hollande and Marine Le Pen, the mainstream Right must urgently reconstruct its leadership, build a party that is coherent, and a policy programme that is not the sum of just a few slogans. At stake over the period ahead is finding the answer to the question of what the mainstream Right’s purpose is, and what it is there to say. There are strong reasons to believe that this cannot wait until the primary election debates in 2016.

Two lines again emerged last Sunday evening. The first is that of former conservative prime minister Alain Juppé – one of Sarkozy’s key rivals for the primaries – when recognizing the defeat inflicted on the LR. “We will need to reflect about the proper manner with which to return to the battle and to win it,” he said, inferring that Sarkozy would only to lose it. Meanwhile, the hardline Sarkozy lead LR candidate for the Rhône-Alpes-Auvergne region, Laurent Wauquiez, commented: “The strength of the Front National forces the Right to rethink itself. The problem is not to talk too much of this, but rather not enough.”

A Front National second-round victory in several regions on December 13th will hand a major argument for all those candidates in the LR primaries who intend locking horns with Sarkozy. Once the results are known they would have easy opportunity to launch their campaigns against the supposed strongman who, for the past two years, has not known how to find the strength to stop the far-right from climbing the steps of power.

-------------------------

The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse