The issue was not raised during the weekly session of questions to the government in the National Assembly. There was just a brief passing reaction from President Emmanuel Macron during a trip to Slovenia, in which he hoped that work on the issue could “proceed clearly and calmly”. And the responses from candidates for next year's presidential election were minimal.

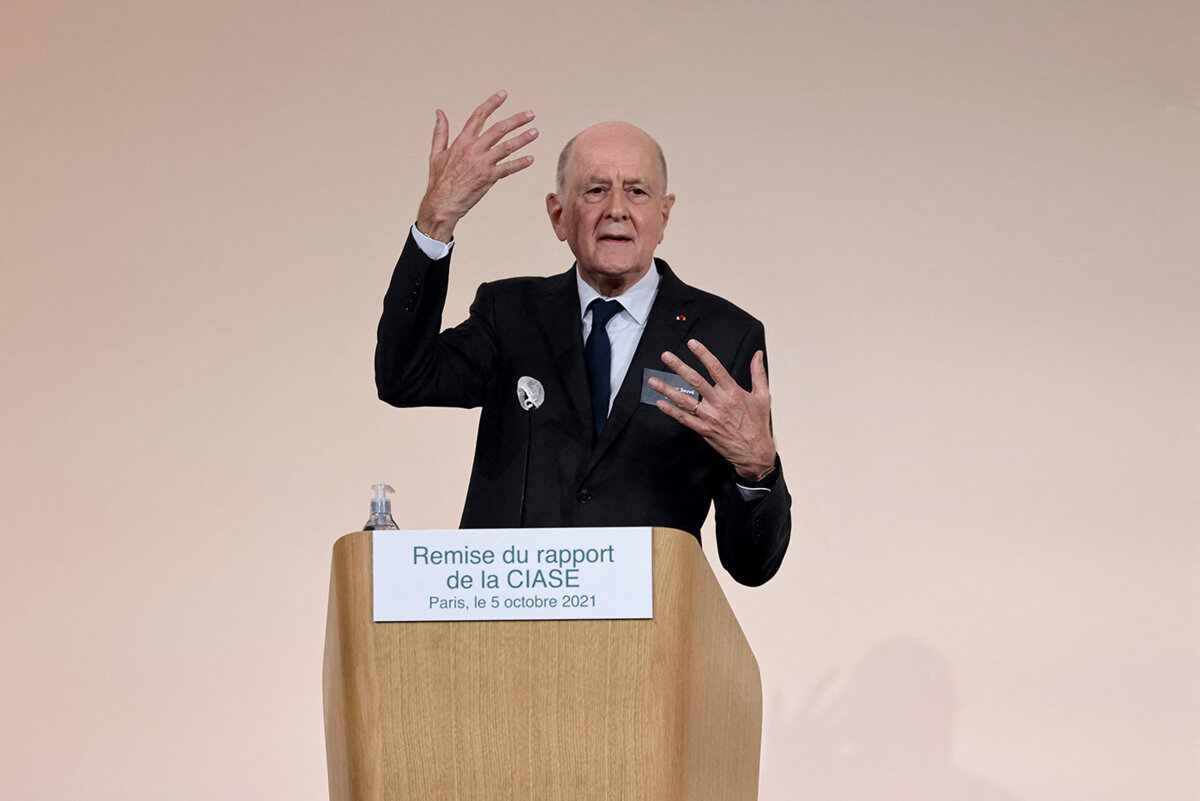

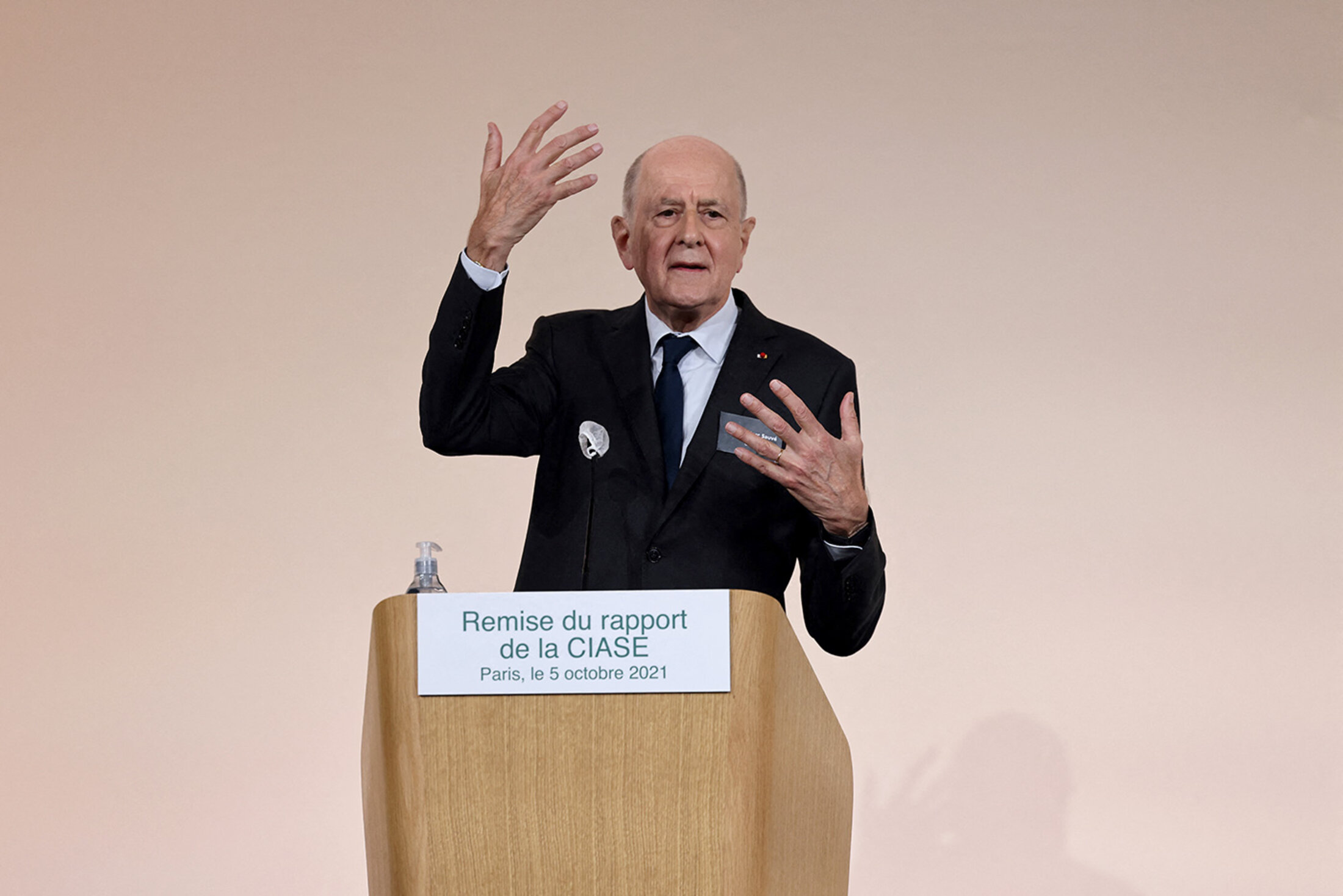

Yet at the beginning of the week, on Tuesday October 5th, a major scandal had broken: according to a report from the Commission Indépendante sur les Abus Sexuels dans l’Église (CIASE), led by senior civil servant Jean-March Sauvé, some 330,000 minors have been the victims of sexual abuse within France's Catholic Church since 1950, victims of both priests and lay workers.

Abroad, similar revelations in recent years have led to strong reactions from senior state figures. In 2012, for example, Ireland's deputy prime minister Eamon Gilmore spoke of a “failure by senior members of the Catholic Church to protect children” and said the head of the Irish Catholic Church, Cardinal Sean Brady, should resign. The cardinal had been accused of failing to warn parents their children were being sexually abused by a priest in the mid-1970s.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In the summer of 2021, meanwhile, the Canadian prime minister Justin Trudeau, himself a devout Catholic, said he was “deeply disappointed” that the Catholic Church had not formally apologised for its role in Canada’s former system of church-run Indigenous boarding schools. This came after the remains of 215 children were found at what was once the country’s largest such school.

“It's not showing the leadership that, quite frankly, is supposed to be at the core of our faith, of forgiveness, of responsibility, of acknowledging truth,” said Trudeau, who pointed out that the government had “tools” at its disposal if the church failed to release documents related to the school. The Canadian premier called on Catholics across the country to reach out to their bishops and cardinals on this issue. “We expect the church to step up and take responsibility for its role in this and be there to help with the grieving and healing, including with records,” he said.

Politicians taking the responsibility to question a religious institution: is this really impossible in a Republic such as France which made the separation of Church and State one of the cornerstones of its very identity?

“The ball is in the Church's court”

Three days after the scandal was revealed, few French politicians had yet come out and adopted a strong stance on this difficult issue. The minister of the interior, Gérald Darmanin, was obliged to break his silence after a senior cleric, Éric de Moulins-Beaufort, president of the Bishops' Conference of France the Conférence des Évêques de France (CEF), declared that “the secret of the confessional [is] stronger that the republic's laws”. But for the most part the government has said little on the matter.

More generally, it was significant that as of Friday October 8th a number of the major presidential candidates for next year, including the radical left Jean-Luc-Mélenchon, socialist mayor of Paris Anne Hidalgo, plus right-wingers Xavier Bertrand and Valérie Pécresse, had not yet spoken out on the issue. Among those who have reacted, such as green presidential candidate Yannick Jadot and the communist Fabien Roussel, they have for the most part confined themselves to social media messages expressing their sympathy for the victims and paying tribute to the work of the commission that produced the report.

The question is: how do politicians tackle this subject, an issue where religious problems, child protection, the law and the battle against sexual violence all coincide?

“Neither the state nor Parliament has the means to intervene, the ball's in the Church's court,” said socialist senator Marie-Pierre de La Gontrie, who argues that the very fact that the Sauvé commission report was commissioned by the Church makes political intervention less easy. “The current work is clearly more accomplished than we could have done, as represented by the unimpeachable figure of Jean-Marc Sauvé,” said fellow socialist senator Laurence Rossignol, who was minister for the family, children and women's rights during the presidency of François Hollande. “His commission had access to the bishops' archives, something we couldn't have got as Parliamentarians because of a lack of resources.”

“The difficulty is that you have canon law and French law side by side,” added Marie-Pierre de La Gontrie, who is nonetheless examining the text of the report in detail to see if some “legislative outcomes” are worth looking at.

The precedent set by the 2018 Parliamentary commission

Moreover, everyone remembers the abortive Senate commission of 2018 set up at the time of the case involving French priest Bernard Preynat, who was later jailed for sexually abusing boys. Marie-Pierre de la Gontrie was one of the Parliamentarians who had called at the time for a Parliamentary inquiry into sexual abuse in the Church. But it came to an abrupt end, stopped by the right-wing majority in the Senate on the grounds that court proceedings were under way, involving both Preynat and also the possible involvement of Cardinal Philippe Barbarin in a cover up – he was later cleared of this on appeal.

“That didn't cause a problem at all in the case of Alexandre Benalla, so it was a fallacious argument,” said Laurence Rossignol, referring to the Senate commission of inquiry in 2018 into the role of Emmanuel Macron's former personal security aide, accused of beating up protesters at a rally in that same year. “In reality it was because the Right was petrified about investigating the Church, and it became instead a catch-all fact-finding mission looking at paedocriminality in all areas.”

Three years later and the idea of a Senate inquiry into the Church is no longer on the agenda, given the immense work just carried out by the Sauvé commission. However, the question of possible compensation is still very much a live issue. The MP for Seine-Saint-Denis north of central Paris, Bastien Lachaud, from the radical left La France Insoumise party, told Mediapart he was thinking of the “hundreds of thousands of victims” and called for vigilance over how any compensation was paid for. “As the Sauvé report notes, the Church should not use funds from voluntary donations, which in the end would cost the taxpayer [editor's note, these voluntary donations from churchgoers benefit from tax deductions that are available for organisations deemed to be in the public interest],” he said.

Embarrassment on the Right

The traditional Right, for whom Catholics are an important part of their electoral base, have struggled to respond to the Church sex abuse report. The president of the right-wing Les Républicains (LR) group in the Senate, Bruno Retailleau, called for the “necessary steps to be taken to ensure that such odious crimes are no longer possible”, and described the report as “traumatic”. However, when Mediapart approached him he did not wish to make further comment.

Annie Genevard, an MP from the east of France, and vice-president of LR, told Mediapart of her “horror at discovering the scale of the phenomenon”. She paid tribute to the “necessary and healthy approach to the truth” that the Church was adopting and said that the report should not go unheeded. “Human justice should run its course,” she said.

An MP from the ruling La République en Marche (LREM), Perrine Goulet, meanwhile said: “Thanks to this report the victims can now understand where they stand, and that's healthy in itself .” She continued: “Those who committed these crimes should now be sent before the courts and we encourage all victims who are not legally prescribed [editor's note, by the statute of limitations] to make a formal complaint.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

However, the MP said that in terms of the criminal law and legislation “all the tools are already available”. Perrine Goulet added: “We're expecting the Church to question itself in order to understand how it got to this point. It must be self-critical.”

However, the LREM MP, who was the co-rapporteur of a report published in 2019 on child protection, said that she still had problems with the way the religious institution was monitored. “We've recently been strengthening the monitoring of criminal records for everyone working with children or volunteers involved with them, and particularly in the domain of sport, but in this case we come up against the issue of the separation of the Church and State!” she said. “And if we make it obligatory for the Catholic religion we will have to do it for all religions, including those where the preachers are not so easily identified.”

“The Church should carry out reforms for the common good!”

“The Sauvé commission did not hide anything and it revealed an alarming and damning state of affairs which in my view calls for a strong response and structural measures,” said Chloé Sagaspe, a youth delegate and member of the executive national bureau of the green Europe Écologie-Les Verts (EELV) party. “If we want to avoid a repetition of this violence, the Church has a responsibility to draw lessons from it. The report's conclusions are in line with investigations that have emerged over the years in France and elsewhere. There must no longer be a guilty silence.”

Robert Ménard, the mayor of Béziers in southern France who is affiliated to the far-right Rassemblement National, was more strident in his approach. “The Church must take another look at some of its habits, some of its dogma, because this can't go on,” he told France Info radio. “You can't fail to draw consequences from what's just happened, you can't explain that that there are 330,000 children who have been abused and then say that you're going to leave it to the good judgement of priests or religious figures when you've seen what a certain number of them were capable of doing.”

“It's an earthquake, there will be a 'before' and an 'after',” said socialist MP Dominique Potier, his voice full of emotion. “To rediscover the light, we must go all the way concerning the full consequences of these revelations.”

Everything that weakens the [societal organisations] concerns us. We mustn't hide behind secular reserve .

The MP, a practising Catholic and president of l'Esprit Civique, a group that works on ideas linking mainstream education with spirituality, believes that the scale of abuse revealed in the Catholic Church should lead to two main courses of action. One is the instigation of criminal proceedings because, he said, “in the spirit of secularism, justice must take its course”; the other is down to the Church itself, which he said must “carry out deep reform”.

Dominique Potier acknowledges the right of politicians to get involved in church affairs. “As a Republican you can want the Church to carry out reforms for the common good,” said the MP for Meurthe-et-Moselle in the north-east of the country. “Like all institutions the Church is a stakeholder in the Republic. We must look upon this affair as if it had happened in a sports federation, because everything that weakens [societal organisations] concerns us. We mustn't hide behind secular reserve.”

The communist MP Pierre Dharréville takes a nuanced view of the affair. “In this tragedy there are things that can come before the courts and I encourage all the victims to go and make a complaint. But with regard to a potential reform of the Church, it's for Christians to hold it accountable,” he said, though he believed that the affair should encourage progress in the fight against sexual violence across all parts of society.

At a time when 70% of complaints of sexual assaults against minors end up being dropped, all the politicians contacted by Mediapart see the Sauvé report as a way of helping to break the wall of silence around paedocriminality in society in general. Ségolène Royal, who was children's minister under socialist prime minister Lionel Jospin in the early 2000s, thinks that “every profession linked to childhood and adolescence should be monitored” and she wondered whether the statute of limitations - which limits the time frame in which charges can be brought - should not be lifted across the board so that “all the predators can be prosecuted”. The government, however, finds it hard to impose reform on the Church authorities.

“Make sure the wall of silence doesn't continue”

Youth organisation such as the Scouts, which is a religious group, are “already subject to the rules that apply to any summer or holiday camp,” noted senator Laurence Rossignol. “And the church clerics who get involved with children rarely have any police record as up to now the institution has closed its eyes. So the revolution to be carried out is first and foremost is a cultural one. Parents who once upon a time sometimes kept quiet will surely not stay silent any longer.”

There is also the issue of how to deal with and forestall problems if upfront checks on personnel are not carried out, which can be hard to implement everywhere. For example, the Church is promising to set up units that will listen to the concerns of possible victims. Yet these will be run by religious figures. “They should be run from outside and by victims associations who are experts in the subject, to ensure the wall of silence that has existed until now doesn't continue,” said MP Perrine Goulet.

Ultimately, Laurence Rossignol thinks that the Catholic Church, which has spoken out a great deal in recent years about issues in society, has emerged “discredited” from this scandal. “When you recall what acts the Church has covered up while, at the same time, it was increasing the number of its instructions to women about contraception and abortion, and was stepping up its condemnatory comments about homosexuality or the family, it should keep quiet – and for a long time.”

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter