There are few visible traces remaining from this episode in post-colonial French history. The first Harki weavers from Algeria to work at Lodève in the south of France are either retired or dead. The housing block where they lived, the 'Cité de la gare', has been pulled down and the corrugated iron sheets of the initial shed-like factory have long since gone. All that remains is a mixture of pride and bitterness, twin emotions that continue to impact later generations of Harkis. “They were very proud of making these beautiful carpets. Part of their heritage was stolen from them,” says Dehiba Noureddine, the daughter of one such weaver.

The story began just after the Évian Accords of 1962 which brought an end to the bloody Algerian war of Independence. At the time Paul Coste-Floret, a former minister for overseas territories who had become mayor of Lodève, a town about 33 miles north-west of Montpellier, wanted to revive the local textile industry by using the weaving expertise of Harki women. The Harkis are the native Muslim French who served as auxiliaries in the French military during the war of independence in Algeria, many of whom subsequently came to France and were shunted into camps.

The job of recruiting the weavers was overseen by the Ministry of the Interior's department that handled people repatriated from Indochina and Algeria, the SFIM. There were three stages to the process: the women were taken out of the Harki transit camps and then hired to work in a factory built from scratch, while their husbands were put to work in the forestry sector under the supervision of the Office National des Forêts (ONF).

To recruit the right women the ministry called on the services of Octave Vitalis, who had himself just been repatriated from Tlemcen in Algeria where he was a workshop manager in a carpet-making firm. He went around the transit camps in the south of France at Saint-Maurice, Rivesaltes and Larzac to test the dexterity of women who were already skilled in the art of traditional weaving. Finally, in 1964, more than 60 families headed for the Cité de la gare, a block of flats just built by the national body in charge of accommodation for Algerian workers, SONACOTRA.

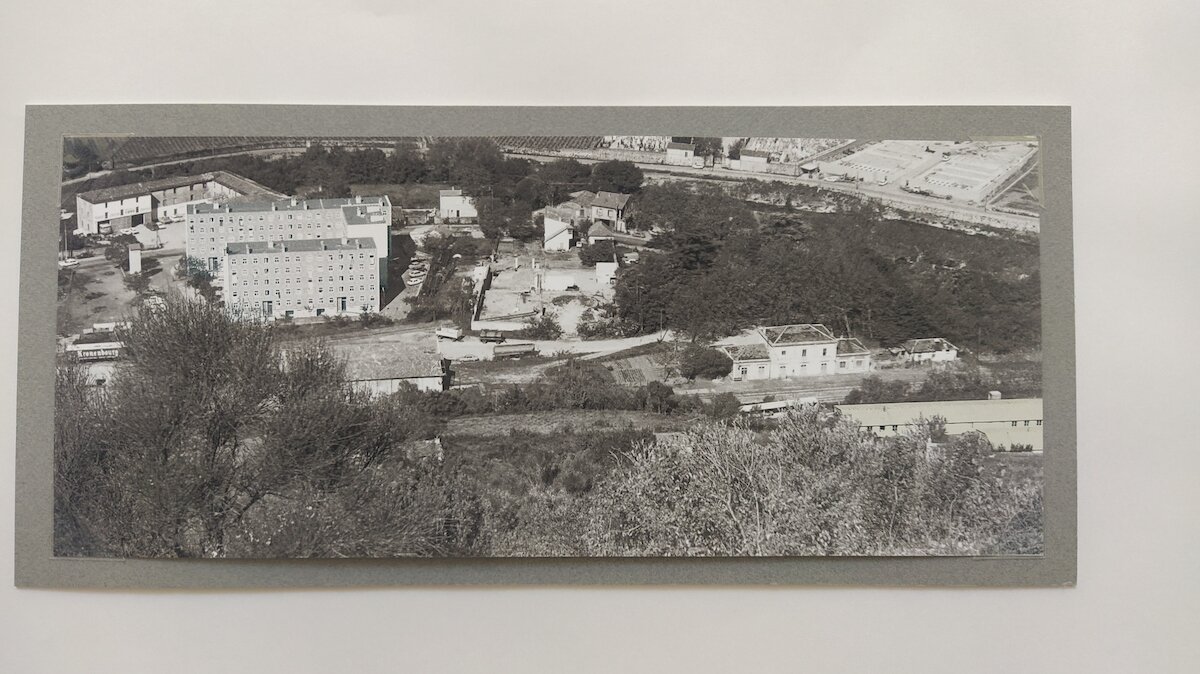

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The three different sections of the apartment block, located on the outskirts of Lodève, formed a kind of 'U' facing outwards. Local historian Bernard Derrieu recalls: “They even had a crèche created so that they could work full-time.” A number of the families who arrived at the SONACOTRA flats had never ventured up such high staircases before. “Some people were very afraid when they arrived here. They also took the doors off their hinges, it wasn't what they were used to,” added Bernard Derrieu, who has co-authored a book on the factory.

Young children were educated in the local primary school but for older children it was different. Zohra Fournier was in the sixième class – equivalent to year seven in England and sixth grade in the United States – when she left Algeria. “But there was no social worker here to help us,” she says. “It was a bit of a mess....I'd have certainly liked to have continued my studies but we weren't offered anything. The only option given to us was a centre where you learnt sewing or cooking. I didn't like it and stopped,” said Zohra Fournier, who quickly went on to join the other weavers after quitting that course.

There was also no support for the mothers, who were not taught to read and write. There was, in short, no education and no future. “We knew that these weren't real jobs, but there was no integration work being carried out. And all these issues still come up today. Every day, in the bars, someone here talks about this history,” says Bernard Derrieu. “My feeling is that, at the time, colonial France came to Lodève.”

From plain rugs to reproduction Louis XVI carpets

In 1965, at the initiative of its minister the writer André Malraux, the Ministry of Culture took over the project and turned the Lodève factory into a local offshoot of the famous Savonnerie workshop in Paris, renowned for its quality, upmarket knot-pile carpets since the 17th century. The Lodève factory's products would thus belong to France's Mobilier National agency, which oversees state furniture and furnishings, and decorate some of the French Republic's most beautiful palaces. But for the women who made them, nothing changed. In their building made of corrugated iron sheeting Octave Vitalis asked them to make kilometres of plain rugs. The output of rows was measured: they each produced around 20 a day.

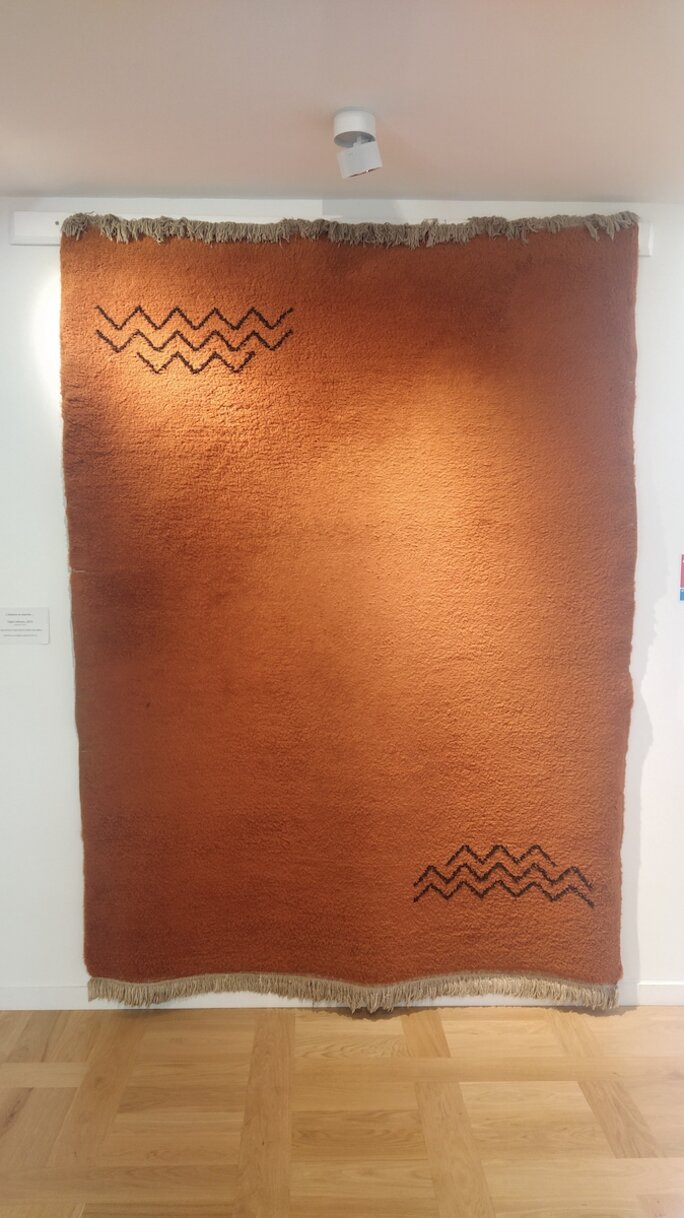

Enlargement : Illustration 2

“If they were two minutes late the person in charge used to close the gate. You had to raise your hand to go to the loo,” says Malika Chaoua, the daughter and granddaughter of weavers. Working conditions at the time were basic. “We were in a shed. When it rained it hammered on the roof. In the summer we were very hot and in the winter very cold. I remember that we were called up by a loud-hailer and handed our money. At the beginning we didn't even know what would become of our carpets,” recalls Zohra Fournier, who worked at the factory from 1966 to 1976.

Each morning the oldest women left the Cité de la gare building side by side and walked to the factory, wearing long dresses with big headscarves. “Our mothers dressed like they did in Algeria. I remember that tourists took photos of them,” says Zohra, still surprised at the memory. Then, over the years, the work got more demanding. Working under the aegis of the Savonnerie, the women were visibly proud when they completed their first reproduction Louis XVI carpets or when they perfected frescoes in the Empire style. However, as local historian Bernard Derrieu regretfully notes, the women's own “Berber cultural input” was “never taken into account”.

The Parisians arrive

In 1991 the corrugated shed at last gave way to a factory worthy of the name and the first 'Parisians' arrived to boost the staff numbers. It was then that the Harki women saw how differently they had been treated. It was a sudden realisation that burst the little postcolonial bubble inside which these mothers had been enclosed.

“We really saw the difference when the Parisian women arrived,” says Zohra. “It was chalk and cheese. They would never have come to the shed … before, we didn't have the right to leave our work station; the women drank tea or coffee on the job while no one was looking. And then when the Parisian women arrived, they had a wonderful kitchen.”

Zohra says that even the quality of the seating changed. There was indeed a whole host of such tiny details, issues that came together when – in vain - they sought to gain promotion. “The factory was created by these women, they did everything, but they always remained at the bottom of the ladder. They were never the people in charge,” says Bernard Derrieu.

I had contributed a lot but when a position of responsibility came up it always went to the Parisians.

In the 1990s several Harki women tried sitting the test to move up a rung but most failed. One such woman was Habiba Kechout, a perennial “second in command”. She tried the test to get promoted but failed the oral test several times. “At the start they said I was too young. Then that I was too shy ...” recalls Habiba. From time to time she took on the responsibilities of a workplace supervisor while a new manager was appointed, but it was only ever an interim appointment.

“My father was a soldier. He gave everything for France but the country turned its back on him.....Years later I experienced the same thing. I had contributed a lot but when a position of responsibility came up it always went to the Parisians,” says the former weaver, who highlighted her grim experiences in the documentary Habiba, directed by Laïla Saïdi.

Weary of her lot, she eventually quit her job in 2003. “I felt it was discrimination. Initially when I left I thought it was mostly about discrimination towards the people of Lodève. … today I wonder if a company as prestigious as that perhaps didn't want an Arab as a workshop manager,” says Habiba. As a result of the years of frustration, plus recurring back pain, she took early retirement in 2009, giving up on several years of pension rights.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Other weavers also came up against a frustrating and unfair glass ceiling. Jean-Paul Vitalis, son of the original factory boss Octave, who was hired some years later, says: “The Parisians and us weren't at the same level. We learnt on the job. Later we did the same work, if not more, but they never acknowledged that.”

Nadia Benfherat, the daughter of another weaver, takes a similar view. “My mother worked there for more than 42 years,” she says. “She didn't manage to move up a level and left with a lot of resentment. She was able to do the work before she arrived in France but was never shown any respect in return.”

The situation was made worse by the fact that when the longest-serving staff retired and looked for their first payslips in order to show their work record and pension entitlements they were unable to find them. “At the start, and for about two years, our mothers did not get payslips. They didn't get insurance cover either. We tried to speak about these issues with the CGT [trade union] later but we found no trace of the documents. It's like they never existed,” says Habiba Kechout.

Alongside the gorgeous rugs in the current building are a few photographs that recall the factory's history. Dozens of visitors stop off here at the workshop to hear guides recount the destination of stylish carpets, while on the first floor around 15 weavers are hard at work making art reproductions ordered by Brigitte Macron in person.

“It was a mixed bag,” says Jean-Marc Sauvier, the person currently in charge of the factory, about the past. “It's one of those rare places where, through Malraux, we took the trouble to help these people. Once they joined the public sector they had the same status as others, and without even taking tests they were accepted as skilled artists,” he says, before putting into perspective the women's role in creating the renowned Savonnerie carpets.

A new vocational qualification related to the arts

“In the beginning they made plain carpets, which were not kept. In terms of ability it was good …. But until ten or fifteen years ago we couldn't put the the Savonnerie mark on their work. We have some knotted-pile carpets in embassies but not in the Élysée or the Senate or the National Assembly,” he says. “And when they made Louis XVI carpets it was under the supervision of the Parisians. This is not to put them down, but everything that was made before the 90s, in the sheds, that was never used.”

Nonetheless, compelled by history – and the feelings of some of the families involved – Jean-Marc Sauvier is setting up a new arts-based course for prospective staff, to attain the Certificat d'Aptitude Professionnelle (CAP) qualification. This is due to welcome its first students in September 2023. It will be open to everyone but the factory boss clearly intends to recruit descendants of the Harkis. “They've often criticised us for not hiring their children. Soon they can take the CAP here and they'd only leave for two years to take the BMA [editor's note, a higher qualification, the 'brevet des métiers d'art']. We'll have come full circle,” says Jean-Marc Sauvier.

The creation of the CAP qualification, in collaboration with the Occitanie region, is taking place thanks to the intervention of local councillor Fadelha Benammar-Koly. She is also vice-president of the local authority covering Lodève and other nearby town and village councils and herself the niece of a weaver. “We have to listen and put things right … I believe that's happening today but it must continue,” she said.

In September 2022 a commemorative plaque featuring the names of all the weavers from the factory since its inception will be put on the front of the current building. A sign on the nearby roundabout at the entrance to Lodève will also remind people of the former location of the Cite de la gare housing block. Supporters hope this is the first stage in an effort to remove the dust that has been swept under the carpet in the past. Habiba, and all the women involved, insist: “We are the history of the Lodève Savonnerie!”

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article, part of a three-part series, can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter