Yaya Camara, now aged 19, arrived in France from his home country Guinea, in West Africa, a little more than two years ago, after a long and arduous path north to Europe, and which he is reluctant to speak about in detail. “I left through Mali, Algeria, Libya, Italy and then France, at the end of 2018,” he said. “It was very complicated, especially between Libya and Algeria. It was very violent, very hard.”

After his arrival in France, as an unaccompanied minor, he was placed in the care of the social services childcare agency, and subsequently enrolled at the regional public apprenticeship training centre (CFA) in the town of Besançon, eastern France.

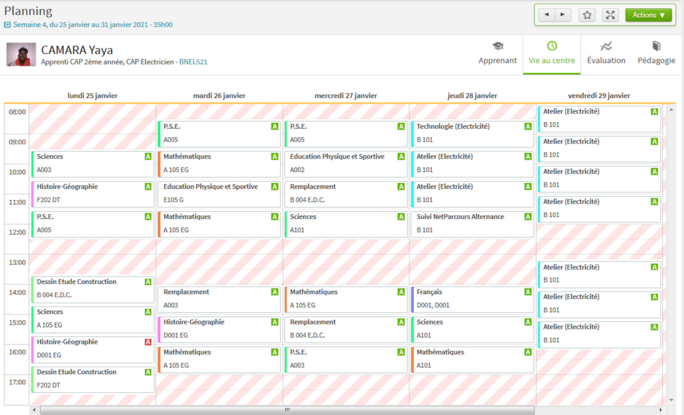

Since September 2019, the young man has followed a training course to obtain a professional aptitude certificate (CAP) as an electrician, dividing his time between class studies at Besançon and on-the-job training three weeks per month with a company in the nearby town of Pontarlier. His employers and teachers speak well of the apprentice, who they say shows keenness and application in his training course.

After turning 18, he applied for a residency permit. But on November 6th 2020, the local government administration centre, the prefecture of the Doubs département (equivalent to a county), rejected his application and delivered an order that he must leave France within 30 days. He took legal action to challenge the expulsion order, called an OQTF, but a local administrative tribunal upheld it on January 26th.

He has in turn lodged an appeal against that ruling, but while he awaits the outcome, he no longer has the right to continue with his training, nor to work for his employers, Robert et Maryse Duarte.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

In January, a remarkably similar story made national headlines in France. This was the case of another young Guinean man, Laye Fodé Traoré, who, like Yaya Camera, arrived in France as an unaccompanied minor, and who also settled in Besançon, where he was employed as an apprentice by a local baker, Stephane Ravacley. After turning 18, Traoré was last year delivered with an expulsion order.

Ravacley was outraged at the move and began a hunger strike in protest. An online petition in support of his demand for the expulsion order to be overturned attracted hundreds of thousands of signatures, and was backed by an open letter to President Emmanuel Macron published in the French press by a campaign group made up of more than 40 actors, academics and politicians. At the end of January, Traoré was given residency status.

“In January, when he saw the case of the apprentice baker in the media, and that everyone was talking about it, he immediately mobilised himself,” said Yaya Camara’s employer, Maryse Duarte. “But he began on his own.”

Without telling anyone, Camara made placards to highlight his case which he displayed outside the local prefecture and the Besançon courthouse. “Following his own initiative, we decided to mobilise,” said his training teacher Raphaël Estienney, who described Camara as a “deserving and well-graded” student. Mirroring the successful campaign for Laye Fodé Traoré, several of the teaching staff, joined by his employers, launched an online petition calling for his deportation order to be overturned.

Traoré’s employer, baker Stéphane Ravacley, who created a collective called Patrons Solidaires (which, roughly translated, means bosses standing in solidarity), heard about Camara’s case and invited him to the press conference organised in January for Traoré, so that “Yaya receives the same outcome as Laye” Ravacley said. He also took up contact with national media such as broadcaster FRANCE 24.

“But we had to cancel everything in extremis when the prefecture sent us an email saying that Yaya was not in Besançon but had been arrested in Orléans on January 28th for not respecting lockdown [measures],” explained Maryse Duarte. Orléans, in central France, is more than 300 kilometres from Besançon. The support committee for Camara halted all further interviews while they tried to clear up what they called an “absurd accusation”. After an exchange of emails, the Doubs prefecture insisted that the young man had lied about his presence in Besançon and his attendance of his apprenticeship course.

In an email sent by Jean Richert, sub-prefect (deputy prefect) for the Doubs, to Maryse Duarte’s husband Robert, and seen by Mediapart, he claimed: “His [Camara’s] presence in Orléans was linked to the fact that he worked as a delivery man for a pizzeria there and that he was arrested by the Orléans police for non-respect of the lockdown regulations. He was the object, by the [local] Loiret prefecture, of a house arrest order in Orléans, for the period while the prefecture of the département organised his expulsion to Guinea.”

“I find it difficult to see how,” continued Richert in his email, “in these conditions he could continue his apprenticeship in the Doubs, except for not respecting the obligations that were his in the Loiret [département in which Orléans is situated], and which in that case could lead to his detention. This case being, henceforth, down to the exclusive management of the Loiret prefecture it is not possible for me from now on to intervene in any manner at all over his administrative situation.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Despite the sub-prefect’s adamant statements, Yaya Camara, together with his teachers and employers, just as categorically dismiss the accusations as untrue. “He was never in Orléans, and on January 28th he was in class,” said his course teacher Raphaël Estienney. According to his attendance sheet, which Mediapart has obtained, Camara was indeed noted as “present” that day at the the CFA training course centre in Besançon. Indeed, three teachers have testified that he was.

“Either another person carries his name, or they stole his identity, or they invented everything,” said Maryse Duarte. “All the same, it’s not difficult to compare his fingerprints with those of the person arrested, but we’re not given an answer.”

Even more bizarre is that the prefecture noted that the person arrested in Orléans reportedly declared he had been living in the town for several weeks working as a pizza delivery man, while there is ample proof that Yaya Camara was in Besançon during that period. He was photographed by local daily L’Est Républicain holding his placards outside the Besançon courthouse in a report published on January 21st, while regional public radio and TV station, France Bleu, photographed him in a CFA classroom on January 26th (and in the Twitter post below). “I also have a photo of him which I took on January 28th,” said teacher Raphaël Estienney.

Yaya Camara et son camarade Nello au CFA de Besançon, après le délibéré du tribunal administratif de Besançon qui refuse la demande de naturalisation de Yaya. pic.twitter.com/PIi1AMN4by

— France Bleu Besançon (@bleubesancon) January 26, 2021

Despite this evidence, the Loiret prefecture, which declined to be interviewed by Mediapart, insisted that Camara was in Orléans and that he is now under house arrest – even though he has no home in the town.

“Today, Yaya can no longer work. He is hidden in a hotel in the Doubs and cannot go out because he fears he will be arrested and locked up in a CRA [detention centre for undocumented migrants],” said Maryse Duarte. No-one knows when the ruling will be made concerning his second appeal against the expulsion order. “In a few days he’ll be in the street,” commented Corentin Germaneau, a member of the Patrons Solidaires collective.

The office of France’s junior minister for citizenship, Marlène Schiappa, also declined to be interviewed by Mediapart, but a source reported that the ministry has now asked the prefect of the Doubs to “proceed with an appropriate study” of Camara’s case. For the moment, neither Camara’s lawyer nor those among the support campaign for him have been given further information about this.

Contacted by Mediapart, Doubs sub-prefect Jean Richert initially confirmed the decision to expel the young Guinean and maintained the claim that Camara was in Orléans. “On January 28th he was intercepted by the Orléans border police [services] presenting the document that was issued to him by me during the processing of his request for a residency permit, a document to which was joined his photograph,” commented Richert. “Taking into consideration that the person concerned was illegally residing in France, the Orléans prefecture ensured his placement under house arrest.”

But the fact remains that that story does not tally with the abundant evidence that Camara was not present in Orléans. Questioned again on Wednesday this week, Richert appeared to finally have doubts about the case made in his previous statements. “Since then, several interventions have placed doubt about the presence of Mr Camara in the Loiret département,” he said. “In order to be able to confirm whether or not there has been an attempt to steal the identity of Mr. Camara by the person arrested in the Loiret, I have asked the Pontarlier inter-départemental director of the border police for an investigation.”

Maryse Duarte said she had received a phone call from the Pontarlier border police in which an officer told her that Camara’s identity papers were stolen and invited the Guinean to visit their offices to make a statement to that effect. “But Yaya doesn’t want to go there because he is afraid that it’s a trap and that he’ll end up in a detention centre,” she explained.

“The documents of Guineans are every time placed in question, it’s not acceptable,” said Corentin Germaneau. “And this story of identity theft is incomprehensible. We’re quite simply asking for a bit of humanity on the part of the prefectures, and for Yaya to be able to finish his studies in all peace.”

Camara can count on the continued support of his support committee, whose members know that his case is far from unique. “There is Yaya who we are defending so that he can remain in France and work, given that he already has a promise for a job,” said his training teacher Raphaël Estienney. “But there are also all the others. At the CFA, there must be 15 percent who are young migrants, and some have just turned 18. If we are fighting today it’s also for them. The least we ask for is that they be allowed to complete their training once they’ve begun it.”

“They are not taking anyone’s place,” he added. “All the more so given that in building or bakery work these are professions where there is a real need.”

-------------------------

- The original French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse