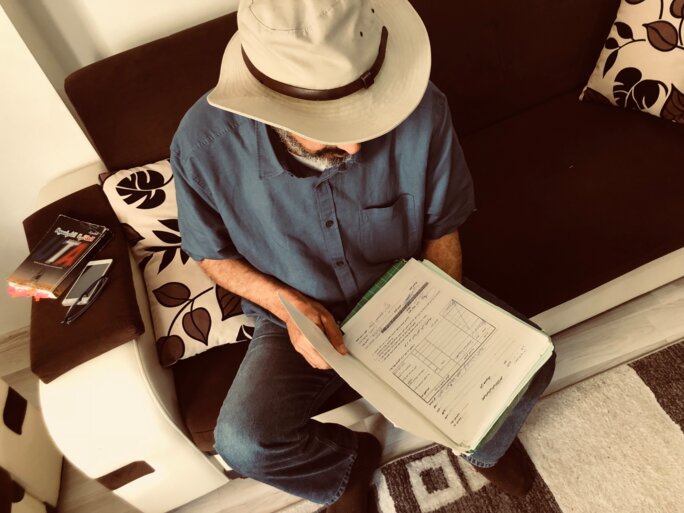

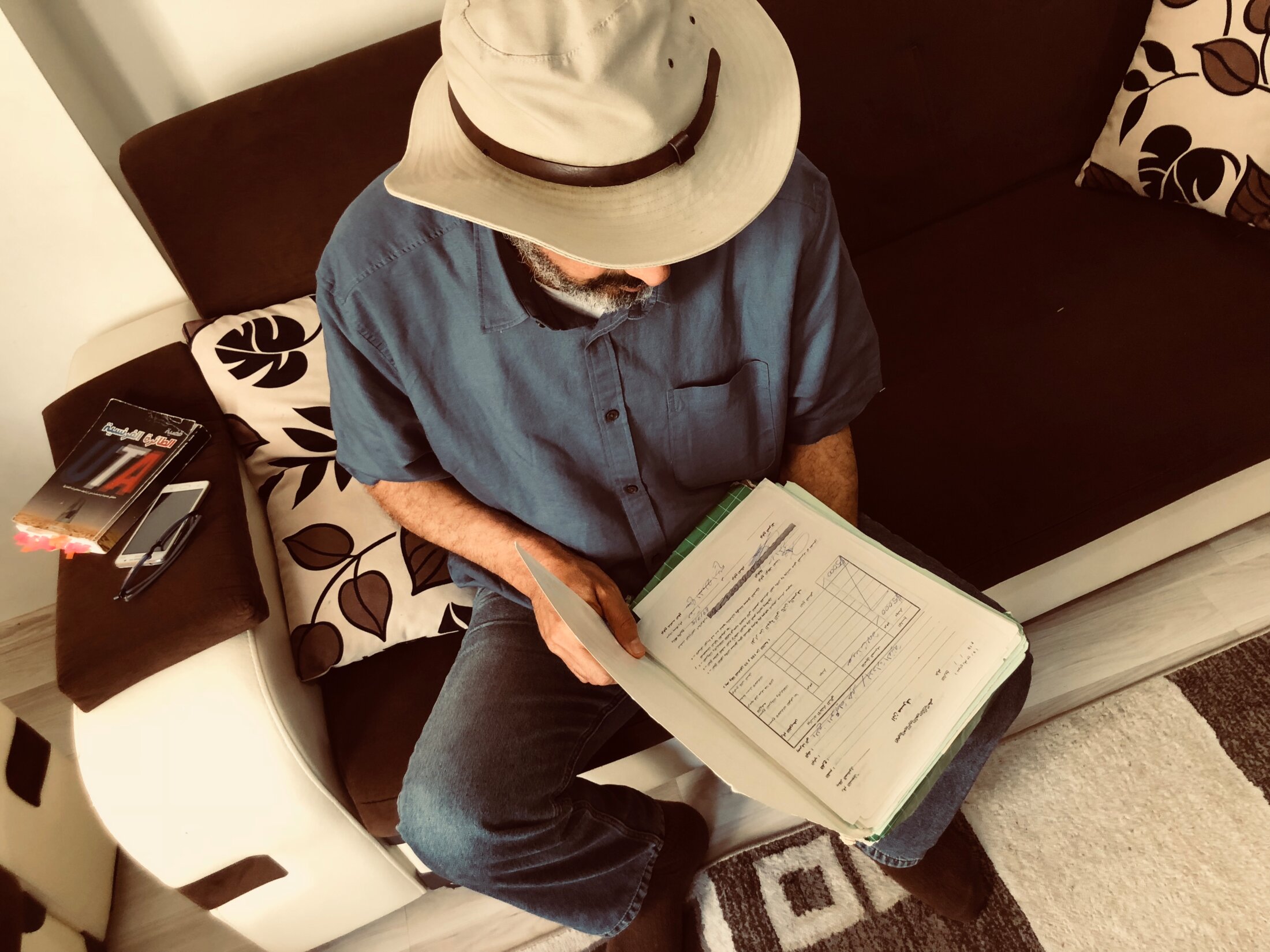

In the June heat, he only removes the bush hat jammed tightly on his head to mop his brow. This is Samir Shegwara, the 52-year-old man man who has helped unearth the old Gaddafi regime's most secret archives on the bombing of the UTA airline's DC 10 airline over Niger in 1989.

A local councillor in Hay-al-Andalus, a prosperous district of Tripoli, Samir Shegwara and a group of revolutionaries obtained extraordinary access to documentation that managed to survive bombings from the Western and Arab coalition during the military campaign against Muammar Gaddafi from March to October 2011.

The green file that he holds in his hands today, and which he agreed to hand to Mediapart, came from the office of Abdullah Senussi, Gaddafi's brother-in-law and security chief. The folder contains dozens of disparate papers, some of them typed, some handwritten. All of them are original documents.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

This is the secret Libyan dossier on the bombing of that UTA flight over Niger, a file complied by Senussi's own secret service. It shows how the terrorist attack was minutely prepared by the Libyan state and how, from 2005, the Sarkozy clan did all it could to find a favourable outcome to Senussi's legal situation in France, after he had been convicted in absentia by a French court for plotting the attack. It is possible this promise of assistance could have been formed part of a deal, in which the Libyans in return agreed to help bankroll Sarkozy's 2007 election campaign. The former president is now under formal investigation by judges over those allegations of Libyan funding. He denies the claims.

Samir Shegwara, who collected the documents and and wrote a commentary on them in a manuscript under the title “The French plane affair”, understands the value of what he possesses. “I'm ready to tell a judge everything. The French and Libyan peoples should know the whole truth,” he insisted during a series of interviews. He spoke to Mediapart in a Middle Eastern city where he took refuge with his family several months ago after, he says, being the victim of an attempted kidnapping in Libya.

Born on January 2nd, 1966, Samir Shegwara grew up in the working class district of Souk el-Jemaa in Tripoli. He has always been interested in paper; in fact it was his trade. Having studied at a business school he worked at the state-run printing enterprise then, in the middle of the 1990s, set up on his own. “I imported paper from Italy, Spain and France and I printed everything: diaries, binders, notebooks...” he recalls. His main client was the Libyan state but at times he also worked for foreign companies based in Libya.

“I had little to do with the very heart of the regime. But the Libyan tribal system means that everyone knows everyone,” says Samir Shegwara. He says he understood his own country and its dictatorial abuses better by reading – illicitly – the book 'Veil: The Secret Wars of the Cia, 1981-1987' by celebrated journalist and Watergate veteran Bob Woodward, published in 1987. It recounts the CIA's secret wars in a number of Arab countries, including Libya.

“After colonisation, Libya was neither under Sharia law or a democracy. It was Gaddafi. Gaddafi was the religion,” explains Samir Shegwara, who says that in private circles he “never hid” what he really thought of the regime. “But you have to understand that, under Gaddafi, there were spies everywhere,” he says. “Some regime officials had already come and told me: 'Samir, we like you a lot, your family is respected, but you must really stop your criticism.”

The Libyan found himself targeted one day after helping a Lebanese magazine Al-Bia Wal-Tanmia ('Environment & Development') published by Najib Saab, which was considered a hostile publication in Libya because of an investigation it had run on the Rabta chemical factory. However, Samir Shegwara, who has written articles on the environment, a subject he is passionate about, was subsequently cleared by an investigation.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Like everyone in Libya, the printer had heard about the bomb that had brought down the DC 10 belonging to airline UTA over the desert in Niger in 1989, killing 170 people including 54 French citizens. “But no one in Libya really knew what had happened. There was no satellite [TV] and the press was completely under the control of the regime,” he says. It took the war of 2011 for the DC 10 attack to became news again.

From the first days of the Libyan revolution, which began in Benghazi in February 2011, Samir Shegwara joined the dissident movement, not taking up arms but raising awareness in his area of Tripoli. He says this led to him being placed under close surveillance by the regime. “You have to understand that it was a home-made revolt, disorganised. Everything went via telephone calls and the internet, but the social networks and emails were spied on by the regime thanks to equipment sold by France, he says. This is a reference to the Eagle software sold to Libya by the company Amesys in 2007.

In April 2011 Samir Shegwara was arrested at his place of work by forces loyal to Gaddafi and placed in detention. “I was hit so much that it took more than a month for the marks to go down,” he reveals. He says he was put in cells run by the regime's anti-terrorist section. “That's how we were considered. As terrorists!” His detention lasted until August 2011, when Tripoli fell and Gaddafi fled. The former dictator was killed that October in Syrte in Libya.

The war in Libya, in which Nicolas Sarkozy's France was a major actor, has left a bitter taste for Samir Shegwara. “At the beginning we were obviously very happy to see a great Western country such as France supporting our cause,” he says. “But personally I quickly got the impression that Sarkozy was playing a double game, that he was waging a war out of revenge. For example, NATO bombed lots of archive centres and even Senussi's house, that's strange, isn't it? Today all the tribes now see that France had a double goal: on the one hand to topple Gaddafi, and on the other to help install Marshal Haftar [editor's note, Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, who controls the east of the country] who's no better than Gaddafi.”

In post-Gaddafi Libya Samir Shegwara became more involved in events. He ran an association for former prisoners, joined an informal group known as the West Tripoli 2nd Division, and was active in politics, being elected a city councillor in 2014. Politically he supported neither of the two strongmen in the counter, neither Fayez al-Serraj, head of the Libyan government recognised internationality but discredited in the country itself, nor Marshal Haftar, who has faced allegations of war crimes.

But Samir Shegwara's most enduring ambitions still relate to paper; in his case, the archives. “In the aftermath of the revolution most people wanted positions, power and money. As for me, I immediately went to look for documents. I collected all I could, everywhere. I even paid people to recover documents so that the memories of the Gaddafi regime's crimes don't disappear.”

This obsession led him to a former civil servant in the Gaddafi regime who managed to get his hands on the file on the attack on the DC 10 in 1989. And the secrets which it contains.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter