Officials in the south of France are drawing up plans that could see some elderly and frail patients denied admission to intensive care as the latest wave of Covid-19 threatens to overwhelm some hospitals there, Mediapart can reveal.

On December 22nd the deteriorating situation in Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur (PACA) led the local health authority to activate level five of its crisis management plan for Marseille and the rest of the region. This involved the postponement of all routine, non-urgent operations. Five days earlier they had begun evacuating patients to other regions.

But the current fifth wave of Covid in France and the new threat from the Omicron variant has forced hospital administrators to plan for the worst in a region which has the country's lowest vaccination rate and an occupancy of intensive care unit (ICU) beds that is already hovering between 90% and 95%. On Tuesday December 29th the country recorded 179,807 Covid cases, with just over a quarter of them involving the new variant.

Over the past week ICU staff at Marseille's hospital authority the Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Marseille (AP-HM) have been drawing up a document formally setting out the criteria to be used for the triage of patients in the city's five hospitals. The discussions about this had begun in early December as various factors indicated a looming crisis. These were the worsening situation in the French overseas départements or counties in the Caribbean, the risk posed by the approaching Omicron variant even before the previous wave had ended, and the catastrophic forecasts based on modelling by the prestigious public health body the Institut Pasteur.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The regional health authority or ARS has asked all its hospitals to consult their ethics committees over how to respond to key issues that are set to crop up in relation to patient care. Meanwhile Mediapart has seen a draft of the working document drawn up by the ICU staff in Marseille. Its very title speaks volumes: “Proposal for prioritisation rules for access to intensive care in case of exceptional shortages due to ICU's full resources being overwhelmed – Covid and non-Covid patients.”

Some of the criteria are shocking. If there are not enough places available in intensive care there are plans to refuse admission to patients over 65 who show no signs of other illness but who are limited in their everyday mobility. “It's not so much about refusing a person over 65 as preferring a person who presents factors with a better prognosis, and in particular when they are younger and less frail,” one of the doctors involved in the discussions about the document explained to Mediapart.

Refusing access to intensive care to patients who could have benefited from it goes against medical ethics.

“Of course this is just preparatory work and sometimes we imagine cataclysmic situations. But these debates should not just remain between doctors, they should be made public,” said the doctor. “It's a real medical failure to end up making these criteria for the triage of patients official, criteria which have incidentally always existed but which have never really been made official in this way.”

“In the most catastrophic scenarios, but ones which are becoming less and less unthinkable in France, we will deny intensive care access to patients who could however have survived,” the doctor continued.

“I am now questioning the very meaning of my profession. Refusing access to intensive care to patients who could have benefited from it goes against medical ethics. Yet that is what we are being forced to think about today in France,” he said. “The government needs to react. We can't do it in a humane way. Intensive care is becoming a luxury treatment.”

Not a new issue for Marseille's hospitals

The PACA regional health authority told Mediapart that “as in the previous waves” it had “activated the ethical units of all the health establishments in the region”. It also confirmed that “consideration is being given at regional level over the care and access to healthcare for patients in a situation where there is great strain imposed by the epidemic”.

At the AP-HM hospital authority in Marseille managing director François Crémieux pointed out that this was an “issue that we've handled for two years in the context of this crisis”. He said: “The issue of prioritisation in intensive care is not a new one. There is no absolute rule that exists which would in principle exclude such or such an ill person: each decision must be taken collegiately by doctors on the basis of shared and transparent criteria that have been decided in advance.”

Carers in the Alsace region in north-east France faced these kind of tough ethical decisions right at the very start of the epidemic, as Mediapart reported at the time. During that same period an internal document from a hospital in Perpignan in southern France also suggested that it might be necessary to “select” patients, through it did not go into any details about the criteria to be used.

The AP-HM boss François Crémieux said the debate should not be reduced simply to one about the number of beds available. “Getting ready to prioritise is also a way of making sure you don't have to do it,” he said. “Because it's not so much the number of beds that poses issues as the very large number of ill people. As this epidemic can be slowed down by vaccination or barrier methods, being aware of the issues over access to intensive care also means a better understanding of the issue of limiting the number of seriously ill people.”

An initial decision about whether to use intensive care is routinely made anyway. It is about making a choice that is in the patient's own best interests, with the doctors making sure than being in intensive care does not constitute excessive treatment. But in the Marseille plan currently under consideration there is no longer a question of choosing in the patient's own interest, but instead an enforced selection. It involves choosing between patients who could all benefit from being in the ICU – and who could all survive.

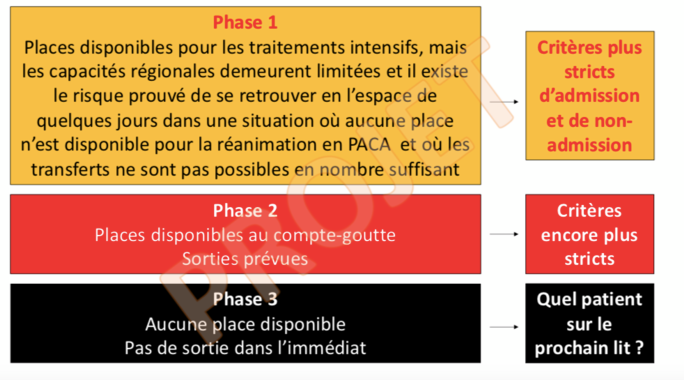

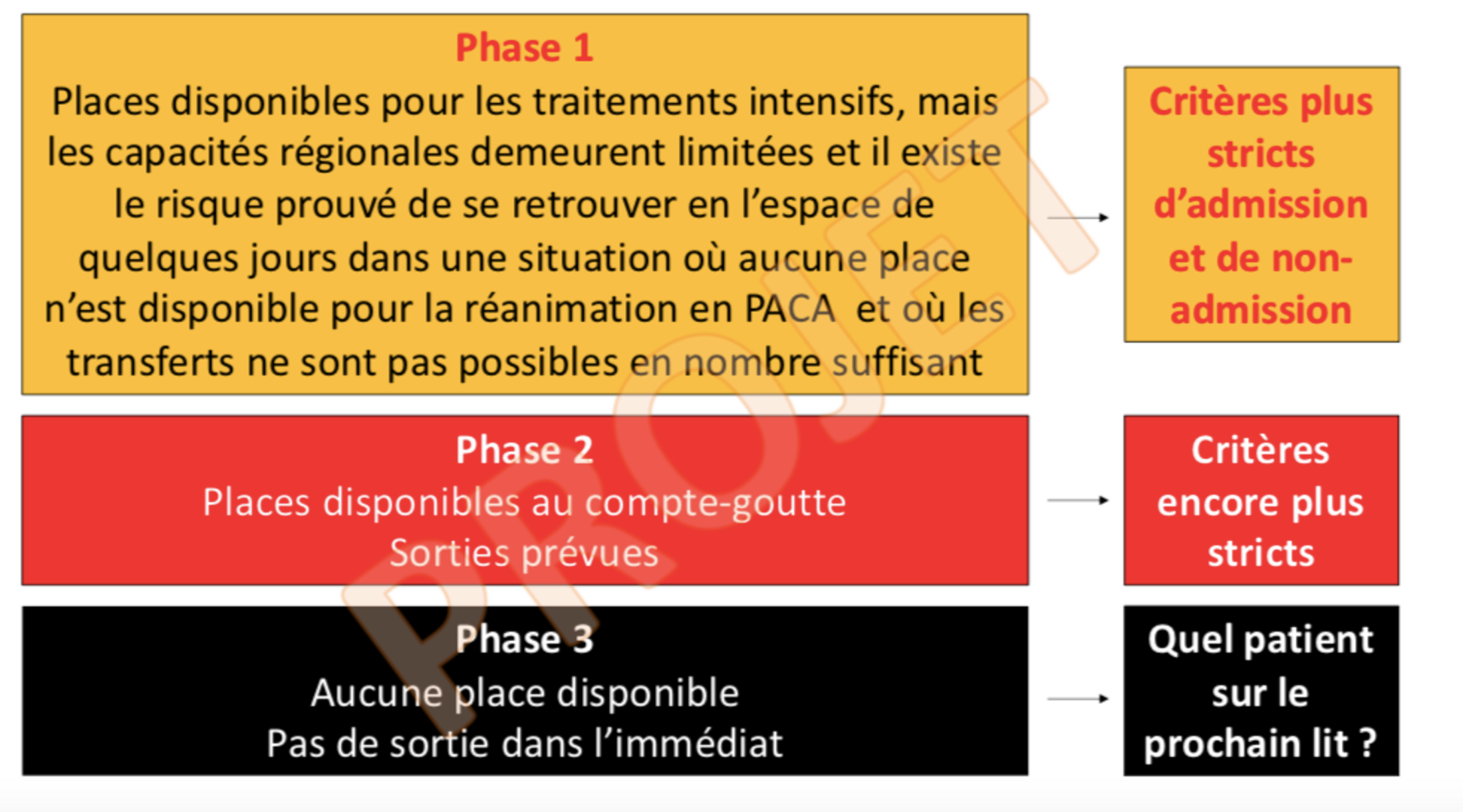

Enlargement : Illustration 2

After three meetings to discuss the issue, the ICU staff in Marseille have so far come up with three different phases. The first phase, which has already been partially activated in the city, applies when there are still “places available for intensive treatment but regional capacity remains limited and there is a known risk that in the space of a few days there will be a situation in which there is no place available for intensive care”.

In the above situation the criteria for admission and non-admission become “stricter”. In addition to a patient not wanting to be treated in an ICU, or someone who is in a life-threatening condition because of very serious co-morbidities, patients who might not be admitted to intensive care include those aged 75 or over who do not have any other illness but who are slightly restricted in their everyday activities. The same would apply to patients whose life expectancy is under a year, whatever their age.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Phase two applies where just a handful of places are available. In this case, stipulates the document, the criteria become “even stricter”. A patient over the aged of 65, who has no other illness, and who has limited mobility, could be refused access to intensive care. Patients who have an incurable illness, for example certain types of cancer, but with life expectancy of two to three more years could also be denied admission to the ICU.

Finally, the third and final phase covers a situation where there is no ICU place available in the immediate future. The appalling dilemma then faced by the doctors is: “Which patient gets the next bed?” It then becomes an issue of “admitting first of all the patient who has one or some intensive care admission criteria with the best prognosis in the short and medium term”. The criteria used for this raise major ethical issues. This is the list of them in in order:

- “Age” with no other condition

- “The level of clinical frailty” which allows a person's dependency to be measured

- “Comorbidities”

- “Severity of organ failure”.

The doctors are keen to reassure people and point out in the document that patients who are refused admission to intensive care can still get an oxygen feed in another bed. Nonetheless, this document marks a new step towards the management of shortages, with the formal establishment of patient admission selection for public hospitals.

Several reports have already tackled this sensitive issue

Is it ethical to restrict access to intensive care for patients aged over 65? Is it ethical, too, for patients who have a life expectancy of two to three years to be denied ICU admisison? Or for patients aged 70 with no prior health issues? That is indeed what is being envisaged, without the public being informed of it.

This sensitive issue was raised as early as March 2020 by France's health and life sciences ethics committee the Comité Consultatif National d’Éthique pour les Sciences de la Vie et de la Santé (CNNE). It stated: “For serious forms the possibility has to be envisaged that certain technical and human resources become limited if the epidemic crisis grows in a major way [….] The need for a 'triage' of patients then poses a major ethical question of distributive justice, which in this case means differentiated treatment for patients infected with Covid-19 and those with other illnesses.”

In April 2021 the Paris regional health authority also approached a group of intensive care doctors to consider this very issue.

Any professional would hate to have to draw up such criteria in the event that health care resources are massively overwhelmed.

One doctor who runs an ICU in a Marseille hospital told Mediapart that rescheduling operations is “already a form of triage or prioritisation”. Since the start of the epidemic, they said, the “prioritisation or triage of patients has often been debated by intensive care professionals in France and in many countries faced with this pandemic. Any professional would hate to have to draw up such criteria in the event that health care resources are massively overwhelmed.” In fact, in Switzerland and the Canadian province of Quebec recommendations along these lines have been made in relation to criteria for selecting patients (read here and here).

“Of course we will continue and indeed have a duty to discuss admissions to intensive care on a case by case basis,” continued the ICU boss. “The fear is that strict admission criteria can be treated as holy writ or as absolute reference point without taking into account the entirety of the situation and its likely course.”

This doctor insisted that at the start of the working document under discussion it is “made clear that one of the prerequisites of the implementation of these criteria is the formal and stated involvement of the political world, civil society, the health authorities and the hospital management, because we're all in the same boat.”

Perhaps we should have raised the alarm more publicly.

“The first to suffer from it will be the patients, followed by all care personnel, who suffer hugely from having to confront such situations. There's a real psychosocial risk,” warned the ICU doctor. “We sought to tackle the health minister over the issue during a video conference. But we don't know if his teams passed on our question. In any case, we haven't had a response.”

Another ICU doctor also pointed out that a majority of the Covid patients in ICU are not vaccinated. But he said there was no question of hiding behind this fact. “The seriousness of the crisis was made worse by a lack of resources and by the government's unkept promise to keep enough ICU beds and staff. Perhaps we should have raised the alarm more publicly,” he suggested, regretting that supposedly well-informed societies had not been clear about the need to maintain human and material resources at a national level.

“In April 2020, when the French Society of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care [editor's note, SFAR] published its recommendations on the 'prioritisation of intensive care treatment in case of reduced intensive care capacity' it certainly did protect the doctors, and helped them face decisions that were sometimes unbearable in human terms,” said the ICU doctor. “But it also opened the door to making the criteria for the triage of patients official. And it takes no courage to raise the alarm publicly about the situation in intensive care units.”

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter