Last year Mediapart revealed how the luxury goods and clothing group Kering, headed by billionaire chief executive François-Henri Pinault, and whose brands include Gucci, Yves Saint Laurent, Bottega Veneta, Stella McCartney and Balenciaga, avoided paying a total of about 2.5 billion euros in tax payments on earnings, via Switzerland. Kering also dodged 50 million euros in Italian taxes on the salary of Gucci's current boss, Marco Bizzarri, by paying him via a company in Luxembourg and using bogus residential tax status in Switzerland.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

New documents obtained by Mediapart and shared with partners at the European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) network, show that Kering used an even worse tax structure to pay Bizzarri's predecessor, Patrizio Di Marco, who was chief executive of Gucci until 2014. The Kering group's boss, François-Henri Pinault, was personally informed about this.

From 2011, on top of his Italian employment contract, Patrizio Di Marco received secret payments as a “consultant” from a Kering front company in Luxembourg, which paid him 24 million euros over five years into the Singapore account of an offshore company based in Panama. This sum was almost entirely exempt from tax, thanks to Swizz tax residency status which was, in reality, debatable.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The biggest winner in this arrangement was Kering. If the group had paid the same amount net to the Gucci boss in Italy it would have cost a total of 63 million euros when taxes are added. In other words it saved the group 39 million euros in taxes and social contributions.

When questioned in 2012 and then 2013 by two commissions of inquiry set up by the French Parliament's upper chamber, the Senate, Kering insisted that it “did not [make] payments to its employees in a country where they did not carry out their main activity”. Therefore the group, which is controlled by the Pinault family, lied to the Senate. However, this will probably not have any legal consequence, for the criminal offense of lying to Parliamentarians does not seem to cover written answers.

Questioned by Mediapart, Kering refused to comment on Di Marco's tax scheme because it “concerns an individual situation and is linked to active judicial proceedings”. The same response came from Patrizio Di Marco on the grounds that “a criminal investigation is pending.” His lawyers said: “Mr. Di Marco is confident about the correctness of his conduct and will demonstrate it before the competent authorities”.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Patrizio Di Marco is a star in the world of fashion. Today this flamboyant personality is the chairman of the luxury Italian brand Golden Goose and sits on the board of Dolce & Gabbana and the French group Sandro, Maje et Claudie Pierlot (SMCP). Between 2008 and 2014 he was the boss at Gucci, Italy's leading luxury goods company and Kering's largest subsidiary. A former colleague describes him as charismatic and approachable which is “rare among such high ranking people”.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

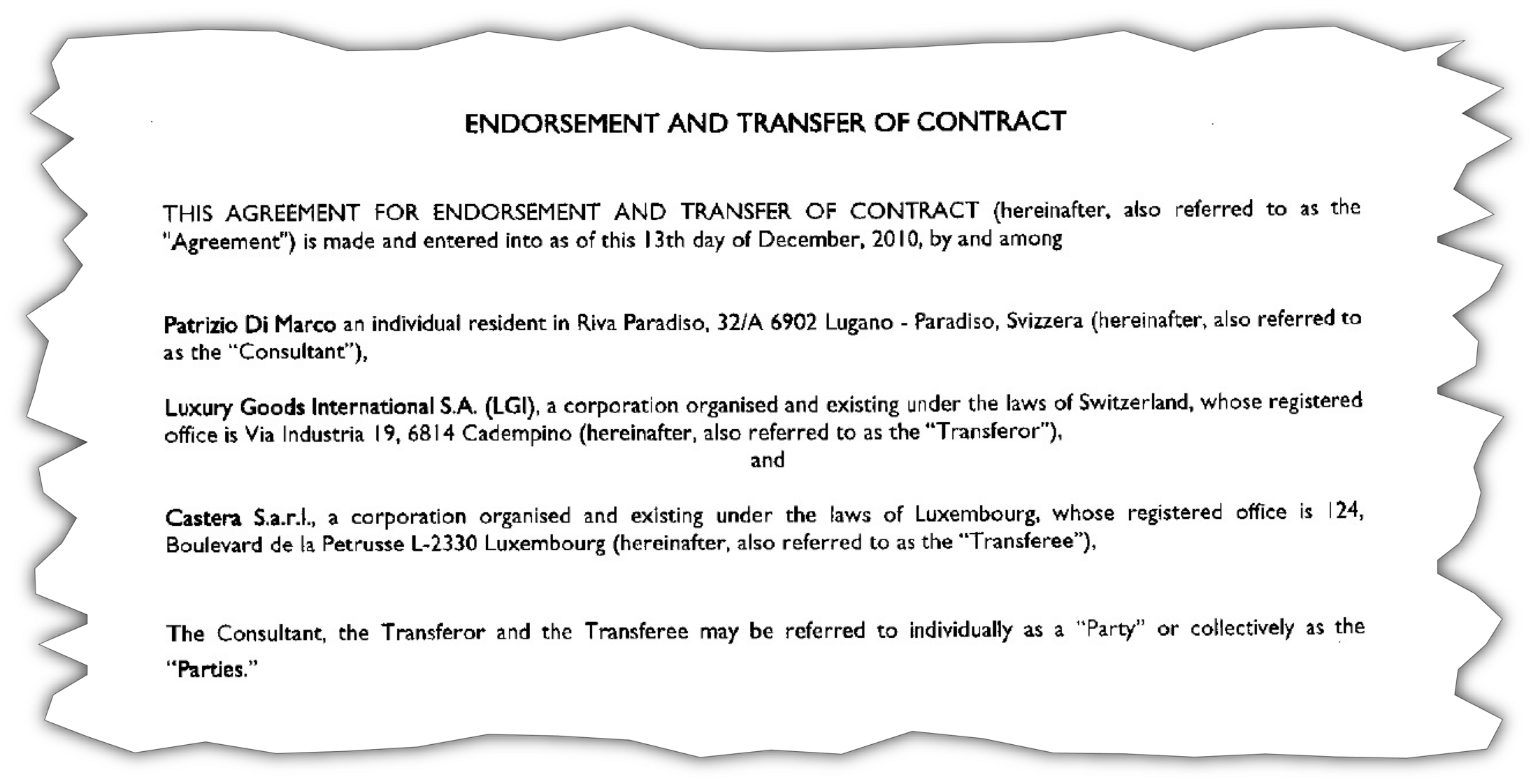

Patrizio Di Marco has also earned a lot of money. His contract with Gucci in Italy earned him one million euros a year gross, on top of which there was a bonus of up to 1.7 million euros, contributions towards accommodation, a 50,000 euros a year clothes allowance, a chauffeur-driven car and the right to travel in the group's private jet. But this was not the only money the Gucci boss received. At the end of 2010 he became the “consultant” for a dummy corporation registered in Luxembourg called Castera (see document above), 100% owned by Kering. Between 2010 and 2014 Patrizio Di Marco billed for 10.7 million euros in fees for his advice, money which was paid to his company in Panama, Vandy International, that he controlled through nominees.

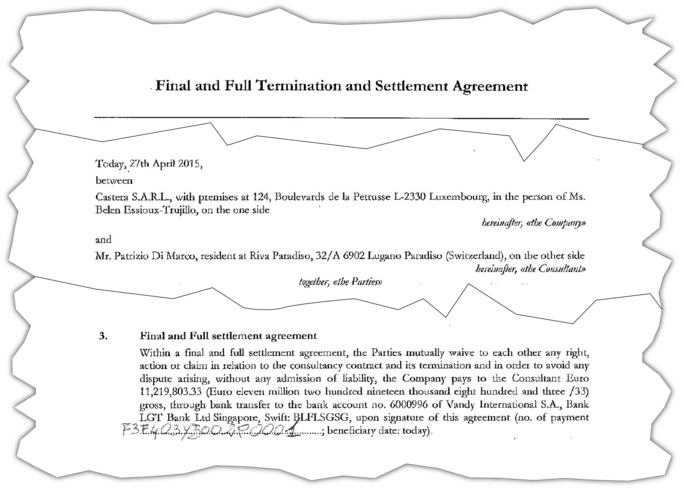

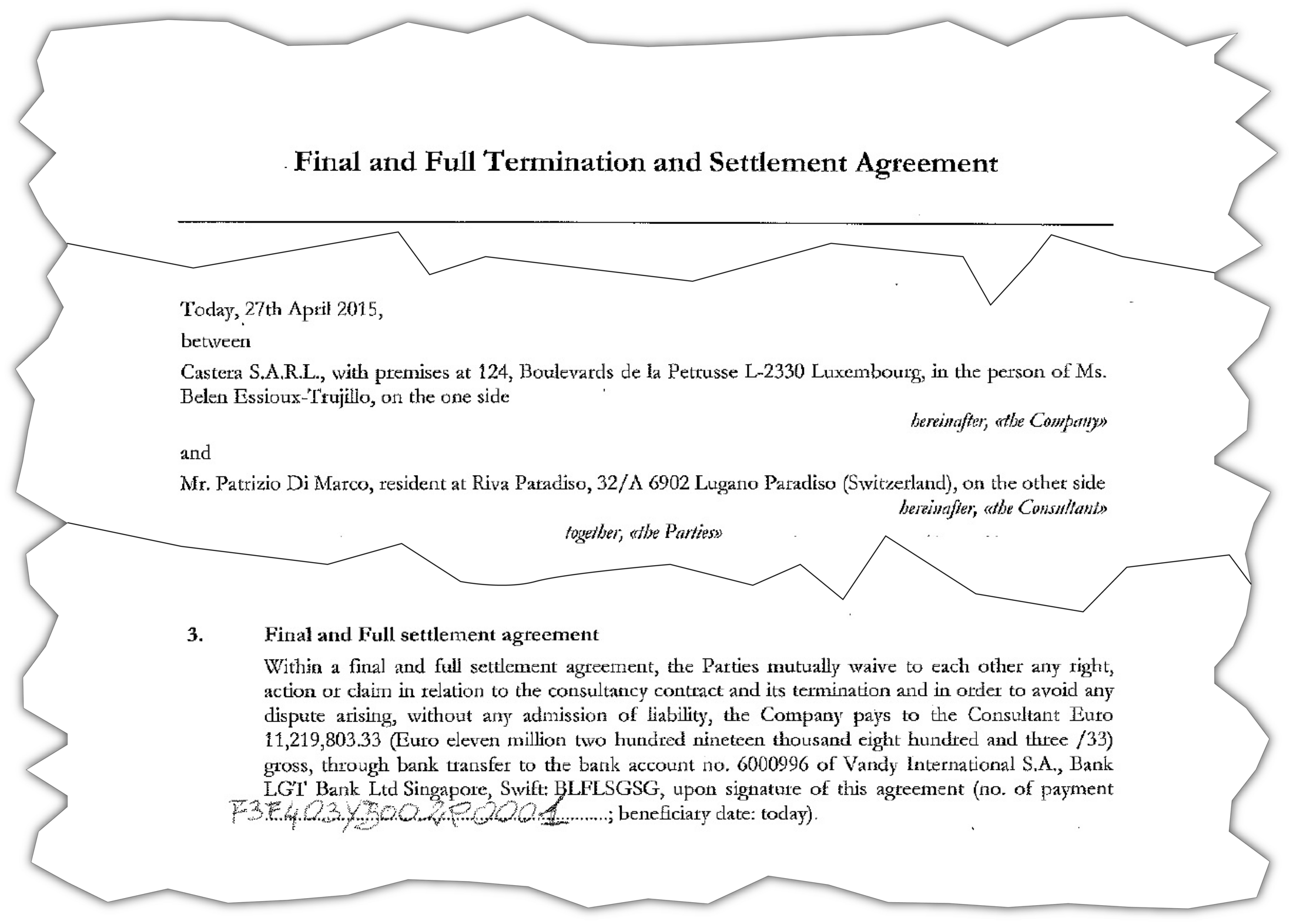

When he was removed from Gucci by François-Henri Pinault in 2014, Di Marco negotiated a colossal severance package: free Kering shares worth 1 million euros, plus a payment of 11.1 million euros. Once again the money was paid to his company in Panama, via a LGT Bank account in Singapore. The document (see below) was signed by the head of human resources at Kering at the time, Belén Essioux-Trujillo.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Thanks to this scheme, Di Marco thus earned 24 million euros on which he did not pay any tax in Italy. His company was not taxed in Panama. And he benefited from a “lump sum” tax residency in Switzerland (also known as “forfait”), a very generous tax regime accorded to just 5,300 privileged foreigners. These ultra wealthy people are taxed on the basis of a “lump sum” which is supposed to reflect the level of their expenditure (400,000 Swiss francs a year in the case of Di Marco).

The result, according to Mediapart's documents, was that the Gucci boss paid around 100,000 euros in income tax in Switzerland. This equates to a rate of 2%, 20 times lower than in Italy.

Officially Patrizio Di Marco lived in Paradiso in the inner suburbs of the southern Swiss city of Lugano. Here Kering rented him a small flat in a large, poorly-maintained block, whose quality seems hard to reconcile with his status as the boss of Gucci.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

In fact he rarely set foot there. As already been reported in the press, Patrizio Di Marco, whose official position was based at Gucci's Milan headquarters, in reality lived in Italy. According to Mediapart's information he in fact owns a 100m2 flat in Milan. And with his wife Frida Giannini he also owns a huge 44-room home in Rome. Was his Swiss residency bogus? He has refused to respond to questions on this.

The scheme had been overseen by Kering. It was the group which helped Patrizio Di Marco to obtain the “lump sum” Swiss tax regime. The operation was managed by a tax expert and trustee in Lugano, Adelio Lardi, who had already created the Swiss organisation LGI which manages the group's tax avoidance scheme.

To benefit from the “lump sum” tax regime a person cannot be paid by a Swiss company. That was why Kering created the company Castera which hired Patrizio Di Marco as its consultant, and then his successor Macro Bizzarri. Luxembourg was chosen as the base for this company because obligatory social payroll payments there are almost nothing and there is no taxation at source for those individuals who live outside the country.

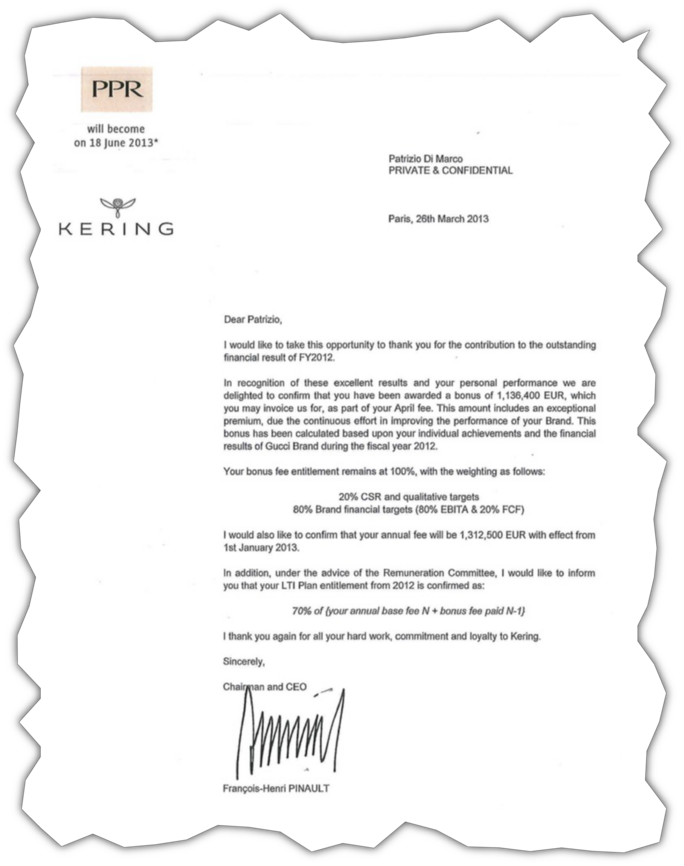

François-Henri Pinault was personally informed of this move. Each year the Kering group boss personally wrote two letters marked “confidential” to Patrizio Di Marco to tell him the level of his bonuses; one for his bonus as an employee in Italy, the other for his bonus as a consultant in Luxembourg.

In his letter dated March 26th 2013 (see below) François-Henri Pinault told Di Marco that he could “invoice” 1.2 million euros as a “fee” of and that he would be entitled to a second bonus based on the group's long-term results whose amount would be fixed “under the advice of the Remuneration Committee” at Kering.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

This letter is embarrassing for the senior figures who sat on this committee at the time. They include Philippe Lagayette, who recently briefly became acting chairman of Renault after the arrest of its boss Carlos Ghosn, Laurence Boone, former advisor to President François Hollande at the Élysée who is now chief economist at the OECD, Jean-Pierre Denis, boss of co-operative bank Crédit Mutuel Arkéa, and Yseulys Costes, CEO of the digital marketing company 1000mercis.

Did these administrators know that the boss of Guci was paid as a consultant, as François-Henri Pinault's letter suggests? Were they aware that Kering paid him his bonus in Panama? None of them responded to Mediapart's request for a comment.

Concern over Senate investigation

In 2012 the French Senate launched a Parliamentary commission of inquiry into “the flight of capital and assets outside France and its fiscal impact” (read report in French here). On May 29th of that year the French Communist Party senator Éric Bocquet, the commission's rapporteur, sent a list of 23 questions to companies listed on France's stock exchange the CAC 40.

At Kering the Senate's move soon made waves. The list of questions was directed to Jean-François Palus, executive director and the right-hand man of François-Henri Pinault. Question number two was particularly embarrassing: “Does the group make its payments (of all kinds) to some of its employees in countries where they don't exercise their main activity?”

“Be careful!” was the reaction on June 4th 2012 of Kering's finance director Jean-Marc Duplaix when the letter arrived at the group's Paris headquarters. He said that “we have to speak about this as soon as possible”. An initial response was drawn up on June 11th 2012 but Jean-François Palus was not happy with it. “Jean-François wants us to shorten it considerably and for us to provide fewer details,” wrote Duplaix.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

The following day, June 12th, Duplaix sent to several executives, including Jean-François Palus, the “expurgated version that I ask you to look at with the greatest care to reassure yourselves that the level of response is at the very least minimal”. However, there were still some “unresolved points” including the question over executives paid abroad. “Jean-François, I think we're certainly along the lines of what you wanted. Please check the part on the paying of employees,” the finance director wrote.

On June 15th, Kering replied in writing to the Senate, stating that it “does not pay payments to its employees in countries where they do not exercise their main activity”.

It is a lie. Two senior executives were paid by Castera in Luxembourg and had a dubious Swiss residency: Patrizio Di Marco and the current Gucci boss Marco Bizzarri, who at the time was boss of luxury leather goods company Bottega Veneta. There is also the twenty or so Gucci managers whom Kering had fictitiously transferred into the Lugano region to lend substance to LGI, the Swiss company which handled the group's corporate tax avoidance scheme (see Mediapart's investigation here).

The Senate persevered. A year later it launched a second commission of inquiry on the “role of the banks and financial players” in tax evasion (read it in French here). On July 29th 2013 Senator Éric Bocquet sent a second list of questions to CAC 40 companies. It contained another question about executives being paid outside the country where they worked. Once again Kering replied that the group “makes every effort never to pay its employees in a country other than the place of their main activity”.

That is not Kering's only lie to the senators. Questioned about its tax optimisation practices, the group replied in 2012 and 2013 that it does not include fiscal policy as an “essential element of its strategy” and that “fiscal concerns are not the primary factor in choosing the legal structure” of its activities abroad.

Yet Kering implemented one of the biggest tax avoidance arrangements carried out by a French company. The group deliberately chose to locate 70% of its profits in its Swiss logistical subsidiary LGI, which is based near Lugano and where the group has negotiated a tax agreement which allows it to pay just 8% corporation tax. That is how Kering was able to escape 2.5 billion euros in taxes (see Mediapart's investigation here).

Contacted by Mediapart, Kering did not want to comment. “The group has nothing to add to its responses made in 2012 and 2013 to the senatorial commissions of inquiry, with respect to the group's situation at that time,” said a spokesperson.

Mediapart sent the documents to Senator Éric Bocquet, who was rapporteur for the two inquiries and a specialist on tax evasion issues. “It's intolerable that a group lies in this way to the Republic,” he said. “Big companies don't make the law and tax law must apply to everyone. If not, consent to taxation will collapse. That's even more important given that the 'yellow vest' movement has again shown the very strong demand for tax justice from our fellow citizens.”

Lying to a Parliamentary commission is a criminal offense that can lead to a heavy penalty: up to five years imprisonment and a 75,000 euro fine under Article 434-13 of the French criminal code. The lung specialist Michel Aubier was handed a six month suspended sentence in 2017 for having lied about his links with oil company Total when he testified in front of a Senate commission.

But senators who want to take action against Kering in this case may struggle to do so. The lie made in 2013 is not timed out under French statute of limitations laws but the criminal code article only seems to apply to false testimonies given orally under oath. The Senate's legal service is however unwilling to rule on this point, as “to our knowledge”, it said, a case concerning a false testimony provided in writing “has not yet arisen”.

Enlargement : Illustration 10

“Your investigation raises the issue of reinforcing the judicial and criminal law arsenal to reinforce the fight against lying to Parliamentary commissions of inquiry,” Senator François Pillet, of the right-wing Les Républicains, who was chairman of the 2013 probe, told Mediapart. “If your documents are corroborated it's quite unacceptable that one can lie to a national representative body in this way.”

Senator Éric Bocquet does not plan to leave the matter there. “If, legally, we may be at an impasse, politically it's a different matter. If we tolerate the top executives of a French group lying to Parliament it's the end of commissions of inquiry. It would be unacceptable for our institution to allow itself be flouted in this way without reacting,” he said.

Finally, Mediapart's investigation raises the question as to the desire of the French authorities to combat tax avoidance by a group as emblematic as Kering, the flagship French luxury goods firm owned by the Pinaults, who are the sixth wealthiest family in France with a fortune of 30 billion euros.

In Italy the investigation by Milan prosecutors into Gucci, who are accused of having evaded a billion euros in tax, was concluded in November 2018. According to news agency Reuters, Gucci risk facing a trial over the allegations.

When Mediapart asked Kering about the end of the investigation and whether it would seek a deal with the authorities or would prefer a trial, the group said of November's development: “It involves a procedural act notifying the parties of the end of the preliminary investigation. Kering is confident about the outcome of this procedure and is actively cooperating, in all transparency, with the relevant authorities.”

In the case in France, where the Kering subsidiary Yves Saint Laurent avoided 180 million euros in tax thanks to the same system, there has been no visible progress in proceedings since Mediapart's revelations in March 2018. When he was interviewed a month later on television by Mediapart's publishing editor Edwy Plenel, President Emmanuel Macron said he was sure that the “tax authorities, when they see a press article like the one that Mediapart has published, they immediately start a tax inspection.... So it's obvious that the affair you're speaking about ...is at the moment the object of a tax inspection.”

But did this inspection ever really start? The French Finance Ministry has declined to comment, saying such cases are protected by the right to secrecy in tax affairs. Kering told Mediapart that “almost all the French entities of the group are the object of a tax inspection, as is regularly the case, which is not unusual for a group the size of Kering”.

A rule in the Finance Ministry is that only the minister of public accounts – currently Gérald Darmanin – is authorised to refer a case to the legal authorities, if the tax authorities consider it sufficiently serious. According to Mediapart's information, no judicial investigation was opened last autumn. The national financial crimes prosecution unit the Parquet National Financier (PNF) declined to comment.

Meanwhile Kering commented on what it claims is the source of the revelations about its tax affairs. In a statement it said: “The source of the different journalistic investigations on the Group's tax system is a former manager whom Kering let go in 2016 for serious misconduct, as soon as the Group was able to show the misappropriations committed by this individual to the detriment of his employer. This manager took advantage of his duties to commit some fraudulent acts to the detriment of the Group by misappropriating several million euros. Kering deposed a complaint for breach of trust with the Milan Prosecutor. Beyond his duties at Kering, this individual was sentenced in October 2018 by the Italian justice system to a 500,000 euro fine and the restitution of 4.8 million euros for insider trading committed at the time of a deal concerning the Italian company Italcementi (which has no link with Kering). He is also under formal investigation in Italy for various offences of a tax nature (non-disclosure of assets and false declaration).”

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter