In November last year, Italian police raided the Milan offices and Florence headquarters of Gucci, the high-flying fashion brand founded in 1921 and now owned by French luxury goods group Kering, as part of an ongoing investigation launched by Milan prosecutors into suspected, and massive, tax evasion by the firm.

Gucci, which last year recorded a leap in year-on-year growth of sales – 49% in the third quarter – is suspected of having evaded an estimated 1.3 billion euros in taxes by declaring part of its corporate revenue in Switzerland rather than Italy.

The raids came as a particularly untimely blow for the reputation of the brand following its recent commercial revival which, in just two years, has made it a feted success story in the world of luxury goods and fashion. Last year Gucci accounted for about two-thirds of the profits made by Kering, the former PPR (Pinault Printemps Redoute) group which owns, among other luxury brands, Yves Saint Laurent, Balenciaga, Bottega Veneta, Boucheron and Stella McCartney.

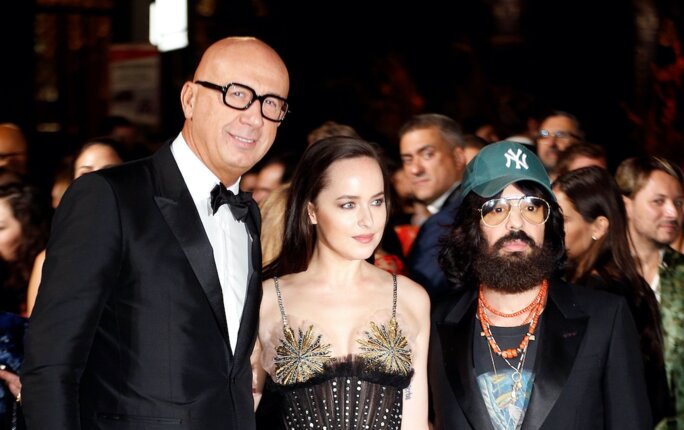

Gucci’s return to success, with a brand value estimated by Forbes last year to be more than 10 billion euros, is widely credited to Marco Bizzarri, who was appointed as CEO to the then struggling firm in 2015. Bizzarri, with an impressive managerial track record already established, hired Alessandro Michele as creative director, a relative unknown whose designs for Gucci, originally founded by Guccio Gucci as a family-owned leather goods business, have since made him a fashion industry star. His collaboration with London-based Spanish artist Coco Capitán has enthused devoted fashion followers, with tops and T-shirts emblazoned with slogans like “What are we going to do with all this future?”, “Common sense is not so common”, and “I want to go back to beliving [sic] in a story”.

At the 2016 London Fashion Awards, Bizzarri was given the title of "International Business Leader" and, last December, he received France’s Légion d’honneur, the county's highest civil award, in a ceremony at the French embassy in Rome attended by Kering chairman and CEO François-Henri Pinault, son of the giant luxury group’s founder François Pinault.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

While the Italian authorities continue to probe Gucci’s alleged tax evasion, documents obtained by Mediapart and its partners in the journalistic consortium European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) show how Kering, with Pinault’s knowledge, mounted a sophisticated offshore tax avoidance scheme which allowed Bizzarri and Kering to escape tens of millions of euros in tax payments in Italy, by remunerating the Gucci boss a net yearly sum of 8 million euros via a shell company in Luxembourg, for which he paid relatively nominal taxes in Switzerland.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

According to the documents obtained by the EIC, the offshore scheme which was in place since 2010 allowed Bizzarri to elude a total of 15 million euros in income tax that he would have been subject to had he been tax-domiciled in Italy, where his business activities are based, and saved Kering 50 million euros.

Neither François-Henri Pinault nor Marco Bizzarri responded to the EIC’s attempts to interview them about the revelations detailed in this report before it was first published in French on January 26th. However, contacted after its publication by Reuters news agency, Kering (to who Gucci referred Reuters), issued the following statement: “Kering has implemented a governance that aspires to ensure full compliance with tax regulations at all levels, including its employees. As regards Mr. Bizzarri, he is fully compliant with his tax obligations in Italy, where he is tax resident.”

Bizzarri, 55, was recruited in 2005 into what is now the Kering group, when it was still called PPR (the group was renamed Kering in 2013). Bizzarri’s first post in the group was as CEO of British fashion house Stella McCartney, owned by PPR’s subsidiary Gucci. After four years, during which, in 2007, Stella McCartney Ltd notably came into profit for the first time, he was appointed as Milan-based head of Gucci-owned Italian fashion brand Bottega Veneta.

In a contract for his new job at Bottega Veneta signed on June 29th 2010, his net annual remuneration was set at 2.5 million euros. Under the contract, Bizzarri was employed by Castera, a Luxembourg-registered subsidiary of what was then still the PPR group.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Castera was in reality a letterbox company, with no employees, managed by strawmen and also, since 2011, successive human resources directors of the French group. Because Castera is registered in Luxembourg, it had very few social welfare charges to pay on salaries.

Bizzarri’s contract stipulated that he was to “accomplish no mission nor any business in Luxembourg” and Castera was prohibited from allowing him the use of offices or secretarial services in the country. In a confidential email message obtained by the EIC, one of the French group’s tax affairs advisors noted that because Bizzarri had no working activities in Luxembourg “his salary from Castera is not subject to income tax in Luxembourg”.

Instead, the contract sets out that Bizzarri is subject to a form of income tax in the Swiss canton of Ticino, which lies just across the border with Italy. Bizzarri at first elected residence in an apartment paid for by the French group in the town of Lugano, before buying an apartment in the nearby hillside village of Vico Morcote, overlooking Lake Lugano.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Bizzarri became one of several thousand wealthy and mostly foreign individuals in Switzerland who benefit from what is known as "forfait" – or “lump sum” – taxation, a system for those who declare no gainful employment in the country and under which, instead of paying tax on revenue, pay a tax levied on their living expenses only. In the case of Bizzarri, his living expenses were first estimated at a yearly 300,000 Swiss francs (about 260,000 euros), which meant that during his more than five years as head of Bottega Veneta, he paid less than 100,000 euros per year in lump-sum taxes, representing 4% of his annual salary, and which was ten times less than income taxes he would have been subject to in Italy.

The arrangement is perfectly legal, on condition that Bizzarri does not spend more than 183 days per year (six months) in Italy (or any other country), a requirement that might appear constraining for the CEO of a major Italian luxury goods firm, especially Gucci with a turnover of more than 4 billion euros. While his residence in Vico Morcote is just 75 kilometres from Milan, the journey by car takes around 1 hour and 15 minutes to complete (or more than two hours by train). When the EIC recently travelled to the small apartment building in Vico Morcote where Bizzarri elected residence, the shutters of his apartment were closed and the letterbox was full.

Kering MD's reveal-all email to Bizzarri and Pinault

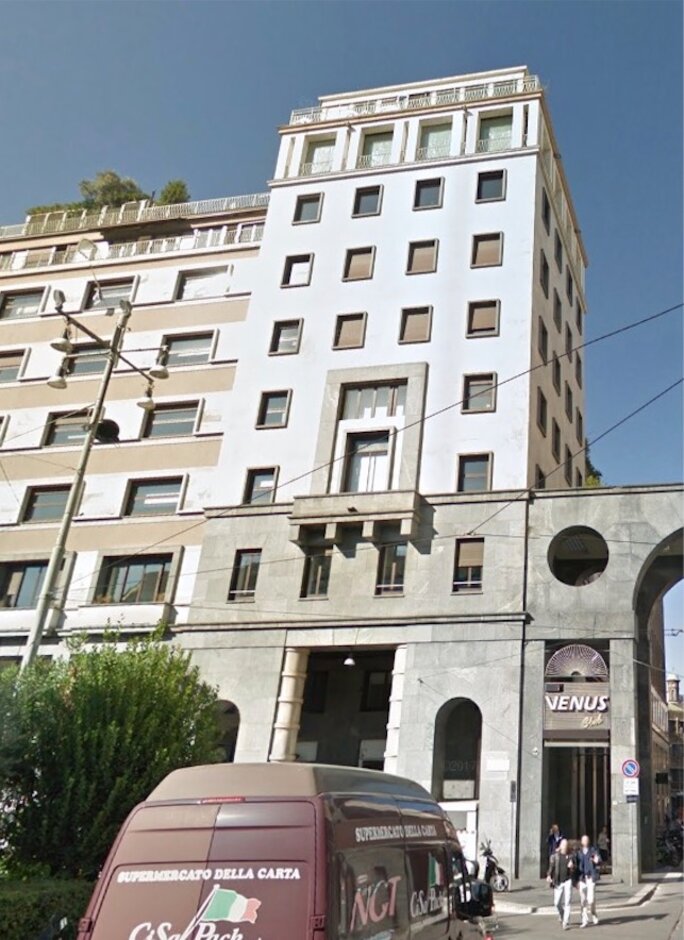

When he was appointed n January 2009 as CEO of Bottega Veneta, a subsidiary of the luxury goods brand signed a four-year rental contract for his use of a luxurious apartment in the centre of Milan. The monthly rent was set at 7,375 euros, plus 2,500 euros in charges for maintenance, housekeeping, and security in the building. The top-floor penthouse is situated close to the Milan Cathedral, the Duomo, with rooftop views over the city.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

Bizzarri’s name does not appear on the rental contract, nor does it figure on the water, electricity or internet services supplied to the apartment. On the letterbox appears only the name of his student son, Stefano Bizzarri.

However, when the EIC visited the location, the building’s caretaker stated clearly that Marco Bizzarri lived there, as several documents also confirm. In an email correspondence which bore the object title “maison Bizzarri Milan”, a management figure from Kering details that Bizzarri wanted to enlarge the space of his Milan apartment by opening it up into the apartment situated immediately below. In 2015, after he was appointed as CEO of Gucci, it was suggested to Bizzarri that the fashion house take over the rental contract from Bottega Veneta, to which he jokingly replied, “But don’t leave me under a bridge”. There was little chance of that, given the huge remuneration for his new post which he had just negotiated with Kering boss François-Henri Pinault.

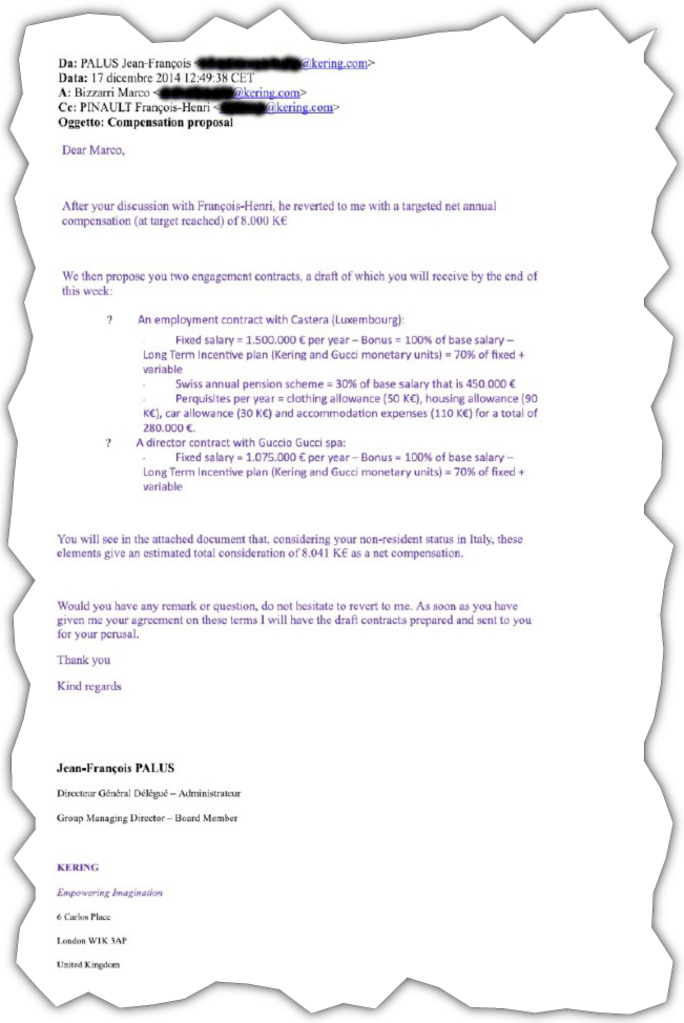

A confidential email (reproduced below) dated December 17th 2014, sent to Marco Bizzarri by Kering Group managing director Jean-François Palus, with François-Henri Pinault copied in to the correspondence, demonstrates that Pinault was directly involved in negotiating the Italian’s new contract. “After your discussion with François-Henri, he reverted to me with a targeted net annual compensation of 8,000K€,” Palus informed Bizzarri in imperfect English.

That equates to a yearly 8 million euros, represents four times the average annual income of CEOs of companies listed on France’s CAC 40 benchmark stock market index.

After detailing the different remunerations that made up the total sum, Palus told Bizzarri that, “You will see in the attached document that, considering your non-resident status in Italy, these elements give an estimated total consideration of 8.041 K€ as a net compensation”.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

If Bizzarri was a declared resident of Italy, in which case the parties would be subject to Italian tax payment demands, in order to provide him with that net sum of 8.041 million euros – i.e. the sum after tax was deducted – the group would have had to pay out a yearly 21 million euros.

Instead, the total cost of Bizzarri’s annual remuneration for Kering was 9.52 million euros, including social charges contributions of just 34,000 euros, representing 0.36% of his income – an income on which Bizzarri would pay 13% in income tax.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

The document attached to the email sent by Palus detailed the social charges and tax payments involved in the contract. In it, Palus sets out that Bizzarri would have two different working contracts. This meant that he would now receive 60% of his total remuneration via Castera in Luxembourg, representing a gross sum of 5.8 million euros on which he would be subject to a tax in Switzerland of 146,000 euros (after his appointment as CEO of Gucci, Bizzarri’s “lump sum” tax liability was calculated on living expenses of 500,000 Swiss francs, up from his previously declared living expenses of 300,000 Swiss francs).

Separately, 3.65 million euros was to be paid by Gucci, on which Bizzarri would be subject to direct tax deductions in Italy of 1.2 million euros, representing a rate of 33% instead of 50% if he was resident in Italy.

Kering chairman and CEO François-Henri Pinault, copied in to the email, was therefore made aware of the tax avoidance scheme, which included the Gucci boss’s status of resident in Switzerland.

Meanwhile, in the Kering group’s official presentations, Bizzarri is described as Gucci CEO, but his contract with the fashion house is as a director, a status which is subject to a lower tax rate.

While it remains unclear why Kering decided as of 2015 that Bizzarri would be paid part of his remuneration in Italy, what is certain is that it would have appeared, at least, highly questionable if it were to be learnt that the boss of Gucci, exposed to the media spotlights as head of one of Italy's most high-profile companies, paid no tax in the country. According to one source contacted by the EIC, Bizzarri decided in 2017 to become a tax-paying resident of Italy, a move which appeared to be confirmed by Kering’s statement issued last Friday (see page 1).

Contacted by the EIC, via the press relations departments of Kering and Gucci, about the issues raised in this article, neither Marco Bizzarri nor François-Henri Pinault responded to our questions, which notably centred on the legality of the remuneration schemes, whether they had been validated by the competent services of Kering and Gucci, and whether other directors of the group were also remunerated via Castera in Luxembourg.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse