It was on November 29th last year when officers from Italy’s financial crime police agency, the Guardia di Finanza, arrived at the offices in Florence and Milan of the fashion brand Gucci. The ensuing search of the buildings lasted three days, when the police also searched the homes of three Gucci directors and questioned the brand’s chief executive Marco Bizzarri.

The raids were carried out on the orders of a Milan-based prosecutor in charge of investigating suspected tax evasion by Gucci estimated to have avoided the luxury goods and clothing firm 1.3 billion euros in tax payments over a period of seven years by declaring part of its corporate revenue in Switzerland rather than Italy, using a financial structure that funnelled funds through Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The subsidiary of French luxury goods and fashion clothing group Kering, formerly called PPR (Pinault-Printemps-Redoute) – which owns, among other luxury brands, Yves Saint Laurent, Balenciaga, Bottega Veneta, Boucheron and Stella McCartney – Gucci is Kering’s highest earner.

Confidential documents obtained by Mediapart and analysed together with its media partners in the journalistic consortium European Investigative Collaborations (EIC) suggest that Gucci’s French owner, Kering, has since 2002 evaded a total of about 2.5 billion euros in tax payments on earnings, mostly to the detriment of the Italian public purse but also that in France and in Britain.

Meanwhile, the documents obtained by Mediapart and the EIC also suggest that Kering haute couture subsidiary Yves Saint Laurent dodged about 180 million euros in tax payments through the same system between 2009 and 2017.

Contacted by Mediapart before this report was first published in French on Friday March 16th, and presented with a list of questions on the issues raised in this report, Kering declined to offer precise answers, nor to grant our request for an interview with Kering chairman and chief executive François-Henri Pinault. However, Kering did send a brief reply by email (click on the "MORE" tab top of page for the full text), the group said that its Swiss subsidiary LGI, through which a large amount of Kering’s profits are channelled, “is an important distribution and logistical platform created in the 1990s, before the taking of control of the Gucci Group by PPR".

"It is at the heart of international distribution activities (managing stock, logistics, billing, management of the supply chain) of the brands of the Group and constitutes an important industrial installation with more than 600 employees," Kering added. "Each of the companies of the Group established in Switzerland exercises a real economic activity directly linked to the commercial activity of the brands of the group. As such, the Group pays in Switzerland taxes due, in accordance with the law and the fiscal status of the company, and its situation is well known to the Swiss, Italian and French tax authorities.”

Enlargement : Illustration 2

However, in a document obtained by Mediapart, the Milan prosecution services describe a “covert” structure established by Kering in order to evade taxes. Most of the documents to which Mediapart has had access are from the Italian judicial investigation into the suspected tax dodge, and they detail the lengths to which the French group went to hide the alleged fraud.

As part of its attempts to justify paying taxes on earnings in Switzerland, about 20 Gucci management staff were presented as being based there, whereas in reality they worked in Italy. As Mediapart reported in January, over a period of seven years, Gucci chief executive Marco Bizzarri paid his personal income tax in Switzerland under a special status that is known as "forfait" – or “lump sum” – taxation, a system for residents who declare no gainful employment in the country and under which, instead of paying tax on revenue, pay a tax levied on their living expenses only.

The revelations of the documents are all the more disturbing in that both Gucci and Yves Saint Laurent have recorded sharp rises in sales and profits over the past three years, described by Kering as “spectacular”, and which was among the most impressive in the luxury goods sector. Meanwhile, Kering has enjoyed a parallel growth, with its 2017 results described as “phenomenal” by the group’s chairman and CEO François-Henri Pinault, posting 15.478 billion euros in consolidated revenue and operating income of 2.948 billion euros. As part of its strategy to concentrate its booming business in the luxury sector, Kering is preparing to sell of its sportswear subsidiary Puma.

François-Henri Pinault, 55, who took over the reins of the family business from his father François in 2005, when the group was still called Pinault-Printemps-Redoute, is not personally targeted by the Italian judicial investigation. However, Kering group managing director Jean-François Palus, together with Patricia Barbizet, who up until last year was chief executive of the 30-billion-euro Pinault family investment holding Artemis, had by last October stepped down from their posts with the companies that made up the offshore structure at the heart of the Milan prosecution services probe.

At the summit of the structure are two letter-box companies, Kering Holland and its subsidiary Kering Luxembourg. The latter owns four companies and two other establishments in the Swiss canton of Ticino, which shares part of the Swiss border with Italy. While officially distinct from one another, the companies are in fact part of a single entity.

The scheme has contributed to building the colossal wealth of the Pinault family for almost 20 years. But the practice was not unique to Kering, as Swiss anti-corruption NGO Public Eye reported in 2016, when it denounced the implantation in the same southern location of Ticino of a number of luxury goods and clothing firms seeking what the NGO called “aggressive tax optimisation”.

The origins of the lucrative scheme go back to 1997, when Gucci created a company called Luxury Goods International, LGI, in Cadempino, a suburb of Lugano with around 1,500 inhabitants, which lies just a short distance from the border with Italy.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

At first, LGI was set up there with just a modestly sized warehouse, whose address was Via Industria 19, situated close to a motorway and at about a one-and-a-half-hour truck ride from Milan. But very soon Gucci decided that LGI was to become its essential logistical centre, and all the brand’s products, most of which were made in Italy, were to transit through it before being shipped to Gucci stores around the world.

According to information obtained by Mediapart and the EIC, a special deal was agreed between the brand and the Ticino authorities, by which it was accorded a company tax rate of 8%, compared with 31% applied in Italy. Gucci gave LGI not only the monopoly of the brand’s distribution activities, but also that of its wholesale business with stores. As a result, most of Gucci’s earnings, and in turn its profits, were paid into LGI.

After the PPR group, now renamed Kering, bought a controlling stake in Gucci in 1999, all the other brands in its luxury goods business, except those centred on jewellery, adopted the same scheme, handing logistical activities and sales to LGI. They included Italian high-end leatherware and ready-to-wear fashion firm Bottega Veneta, British fashion houses Stella McCartney and Alexander McQueen, and French fashion houses Yves Saint Laurent and Balenciaga (formally Spanish).

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Two other warehouses were subsequently built by the group in Ticino to cope with the logistical demands of its growing brands. The most recent was opened in 2014 in Sant'Antonino, about 15 kilometres north of Lugano. There is no sign outside identifying the owners of the building, which has a surface area of about three football pitches, but inside the site trucks come and go shifting batches of dresses, shoes and handbags and other luxury goods which are prepared at a rate of around 2,000 packages per hour.

“It’s the effect of Kering in action, from Sant'Antonino to the whole world,” exclaimed Kering managing director Jean-François Palus during the inauguration of the warehouse in June 2014. According to information gained by Mediapart and the EIC, between 2009 and 2017 LGI posted a total net income of close to 7 billion euros, representing 70% of all the Kering group’s profits over the same period. Meanwhile, the number of staff employed by Kering in Switzerland is about 600, which is less than 3% of all the employees in its luxury goods division.

The figures translate into a tax avoidance over the same period of about 2 billion euros, a sum which includes 1.4 billion euros that Gucci would otherwise had to have paid in Italy, and 180 million euros that Yves Saint Laurent would have been liable for France.

Kering is not the only one to use the lucrative scheme in Ticino; high-end brands including Armani, Hugo Boss, Versace and The North Face have created logistical sites there for the same reasons. While the fiscal deals firms have obtained from the Ticino authorities remain strictly confidential, an official document produced by the Swiss canton reveals that businesses in what it calls its “Fashion Valley” – which in reality is made up of a series of warehouses rather than designers’ studios – provides its largest source of revenue.

In its 2016 report “Case study: the Ticino Fashion Valley”, Swiss NGO Public Eye describes the scheme as “fiscal piracy” that operates to the detriment of other European countries. The report noted: “While fashion multinationals – and their shareholders – each year accumulate millions in profits by using such tax strategies, the people who make their products in the factories of their suppliers and sub-contractors are paid miserable salaries. In Asia as in numerous European countries, the salaries of textile workers do not meet subsistence level.”

The Italian prosecutors appear to regard the system as also essentially illegal: while in the case of Kering, its Swiss subsidiary LGI officially sells products of the brands to stores worldwide, such activity is carried out by employees of the brands in Paris, London and Milan. For although those who work in the warehouses in Switzerland may be highly efficient, it is improbable to imagine that they alone create about 70% of the income from the luxury labels that are among the most prestigious in the market. In businesses in general, logistical activity has little added value.

But in the scheme used by Kering, it is the warehouse business that receives the income, and in turn remunerates, for example, Gucci or Yves Saint Laurent a minimal amount as a sort of licence fee. In the case of Gucci, the system allowed the brand to pay only about 100 million euros in taxes in Italy over the period 2013-2016, instead of about 650 million euros if the profits declared in Switzerland were declared in Italy.

Gucci, an icon of Italian capitalism, is one of the biggest luxury goods brands in the world, with a turnover in 2017 of more than 6 billion euros, and provides 70% of the Kering group’s earnings.

'Based' in Switzerland, with offices in Milan

Documents obtained by the Milan prosecution services show that Kering altered the employment contracts of about 20 Gucci management staff to transfer their working base from Italy to Switzerland. The manoeuvre not only helped to justify the purported importance of the brand’s activities in Switzerland, but also removed from their salaries the social contributions paid in Italy.

On June 15th 2012, Gucci’s labour law advisor sent an email to the brand’s human resources director with the heading “List of CH people – confidential”, (the letters CH referring to Switzerland, as the Helvetic Confederation). The email contained a list of ten managers. The human resources director, along with two of her staff and also the head of security at the brand and the director of its shoe division had been officially transferred to Switzerland one month earlier, on May 15th.

In the June 15th email, the labour law advisor wrote, “We are going to define over the coming days the passage” of two managers, one of whom was in charge of the operations of Gucci’s stores in Europe. It also noted that the cases of three other managers, who included the heads of the marketing and merchandising divisions, “still have to be confirmed” – which in fact they later were.

Most of those cited became employed directly by Luxury Goods Services (LGS), a Swiss shell company registered at the same address as LGI in Cadempino which had no other activity than that of employing those transferred to it. The head of LGS is Béatrice Lazat, director of human resources for the Kering group, indicating that the whole operation was overseen from the group’s headquarters in Paris.

The staff officially transferred to Switzerland were given email addresses with Swiss identification (@ch.gucci.com). According to one witness questioned by Italian police in their investigations for the Milan prosecutors, the group also supplied those transferred with “company cars with Swiss number plates, and Swiss mobile phones”. The witness said they were “encouraged” by Gucci “to transfer their personal residence to Switzerland, including by financing the cost of their homes”.

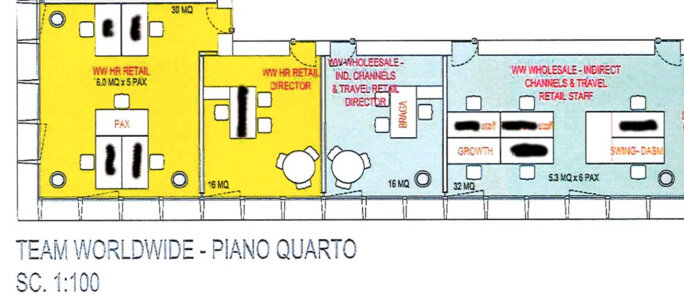

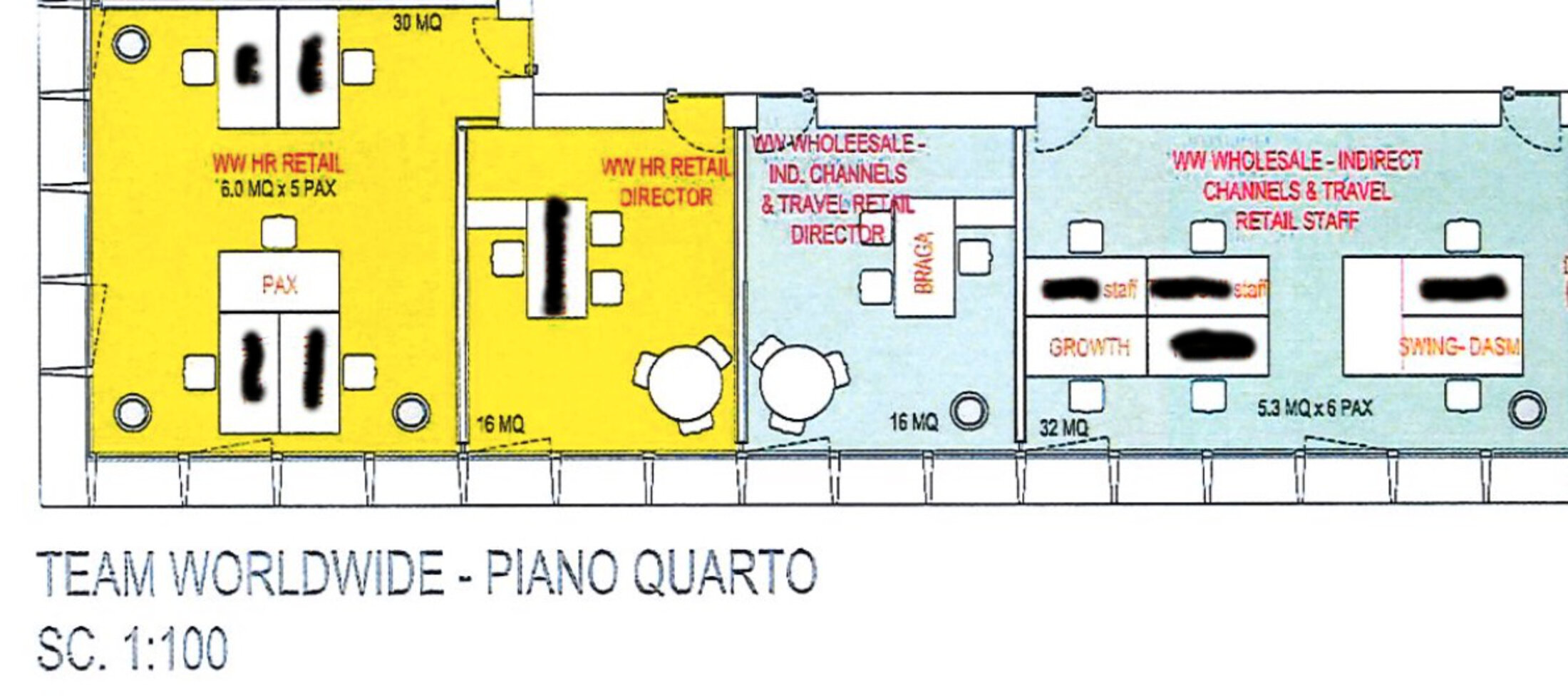

But internal email correspondence and a plan of the Gucci office building suggest that staff supposedly transferred to Switzerland in fact continued to work in Italy. More anecdotal was the presence of Swiss-registered cars seen on the parking slots of the Gucci Hub, the new centre the brand opened in Milan in 2016 in a converted factory on the via Mecenate.

Piero Braga, Gucci’s director of sales for Europe and the Middle East, whose home was raided in the Guardia di Finanza operation at the end of last November, was promoted on February 21st this year to a new four-strong executive committee that works alongside Gucci chief executive Marco Bizzarri.

Enlargement : Illustration 6

Gucci’s sales are officially managed by LGI, and Braga was one of those transferred from an Italian employment contract to a Swiss contract. On his LinkedIn profile (see above), he describes his working base as Ticino. But, according to the floor plan obtained by the EIC (see below), Braga has a 16 square-metre office inside the Gucci Hub in Milan, where he also has an apartment. The floor plan shows the offices adjacent to his inside the Gucci Hub are occupied by his principal staff, including his assistant, most of whom are officially based in Switzerland. Also suggesting Braga in fact works in Milan are internal emails seen by the EIC in which his assistant organised meetings for him held at the Gucci Hub.

Enlargement : Illustration 7

Another person recently promoted to join Marco Bizzarri’s executive committee is the brand’s marketing director Robert Triefus, who was also a target of the police raids. Triefus has been officially based in Cadempino in Switzerland as an employee of LGS since 2012. But he too has an office (of 38 square metres) at the Gucci Hub in Milan, where also work members of his team, including his personal assistant.

Another case that raises questions over the transfers of staff to Switzerland is that of a former senior management figure who recently left the group. While given a Swiss employment contract, he was in fact based with his assistant at Gucci’s offices in Florence. Gucci had attempted to obtain for him Swiss residency under the "forfait" – or “lump sum” – taxation status which was enjoyed by Marco Bizzarri. Several thousand wealthy and mostly foreign individuals are granted the highly privileged status in Switzerland, on condition that they are residents of the country and spend no more than 183 days per year in another. Gucci’s move was finally turned down by the Ticino authorities because he was “only very rarely” in Switzerland.

As Mediapart revealed in January, Gucci chief executive Marco Bizzarri was however granted the “forfait” tax status by Switzerland, where he bought an apartment in the hillside village of Vico Morcote, close to Lugano. Under the scheme, instead of paying tax on revenue, a tax is levied on living expenses only. In the case of Bizzarri, his living expenses were first estimated at a yearly 300,000 Swiss francs (about 260,000 euros). Although it is unclear whether Bizzarri in reality met the requirements of the “forfait” system, notably residing in Switzerland for most of the year, he benefitted from it for a period of seven years, escaping about 15 million euros in taxes if he had otherwise declared his oncome in Italy, as part of a scheme that was personally validated by François-Henri Pinault.

Enlargement : Illustration 8

According to the documents now obtained by Mediapart, Bizzarri disposed of an 88 square-metre office at the Gucci Hub in Milan, and also a bathroom and private meeting room. His assistant was officially based in Kugano, and possessed a Swiss-registered mobile phone, although she was given an adjoining office to that of her boss and organised meetings at the Gucci Hub. She recently modified her LinkedIn page to declare that she no longer works in Ticino and is based in Milan.

Meanwhile, Kering set up an offshore-style financial structure through which the vast profits of its Swiss operations were funnelled out of the country. The group’s swiss companies belong to Kering Luxembourg, which itself is a subsidiary of Kering Holland, a company registered in the Netherlands and where François-Henri Pinault was co-director over a period of 15 years, beginning before PPR was renamed Kering. Kering Luxembourg, which owns a number of the brands in the group’s luxury goods division, receives payments from LGI in Switzerland, and manages the internal financing of the subsidiaries. The surplus left over is sent to Kering Holland, which can redistribute the funds tax-free.

While Kering Luxembourg and Kering Holland appear to have no other purpose than to benefit from the tax rates applied by both countries on financial transactions, in its email reply to Mediapart (cited on page 1), the Kering group insisted that their "existence does not provide a tax advantage to the Kering group”.

Kering also added that, “it is a falsehood to say that Kering Luxembourg SA has no activities nor staff in Luxembourg”.

Both companies are managed for the most part from Switzerland. Kering Luxembourg, whose directors are a local tax advisor and several senior figures from Kering, is based in modest offices of just 22 square metres in a building it shares with other companies. Most of its 13 staff are based with the its two companies in Switzerland at Cadempino, in the same building as LGI.

Enlargement : Illustration 9

Kering Holland is based on the 13th floor of an office block skyscraper in southern Amsterdam, the “Rembrandttoren”, or Rembrandt Tower. At its origins, it was initially called Gucci Group, the parent company of Gucci after the brand was quoted on the Amsterdam stock exchange in 1995. But after the controlling stake in Gucci was acquired by PPR in 1999, and with the departure of the brand’s last minority shareholders in 2012, the company would appear to no longer have its original purpose.

According to information obtained by the EIC, Kering Holland is in reality managed from Cadempino, and operates through Swiss bank accounts in Lugano. According to its most recent published activity report, it has just one employee based in the Netherlands. The EIC was informed that the employee is a Dutch administrative assistant named Nicole Plieger, who apparently does not attend the offices on a daily basis.

When the EIC visited the multi-office building, the receptionist said she had not seen Nicole Plieger that day, and refused to allow us access to the floor where Kering Holland is situated. Shortly after that visit, Nicole Plieger called the phone number left by the EIC reporter. During the conversation, she said she was the “manager” of the company. Asked whether she was the sole employee, she replied: “That’s not true, there are three of us there.” Nicole Plieger refused to answer further questions and advised the EIC to contact the Kering group press office in Paris. Pressed further with the question of why Kering Holland is based in the Netherlands she said, “I am certainly not going to answer this question because we have been told not to. Do you want me to lose my job?”

Kering chairman and CEO François-Henri Pinault resigned from his post as co-director of the Dutch entity on October 5th 2016, six months after the opening of the judicial probe in Italy. At the end of 2016, Kering group managing director Jean-François Palus stepped down from his post as chairman of LGI, and in July 2017 resigned from his position as an administrator of Kering Luxembourg.

Enlargement : Illustration 10

Meanwhile, Gucci chief executive Marco Bizzarri regularised his situation with the Italian tax authorities in 2017, which one source told the EIC involved the payment of a large sum. In an interview with French daily Le Monde following the publication in January of our revelations into how Bizzarri had escaped millions of euros in income tax payments, François-Henri Pinault said: “It’s a non-subject. He is an Italian citizen [who is] in order with the fiscal regulations of his country.”

Just why Bizzarri finally decided to settle with the Italian tax authorities is unclear, although the Italian authorities had set a deadline of the end of 2017 for tax exiles to be able to put their situation in order without facing criminal proceedings or penalty payments. For the time being, he is the only senior management figure in the Kering group targeted by the investigation into alleged tax fraud by Gucci.

Mediapart and the EIC sent a long list of questions to Gucci, Marco Bizzarri and his assistant, Piero Braga, Robert Triefus, and also to the former human resources director of the brand, but they offered no response.

-------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.