She ran up 23,000 euros in debt with her family in order to pay for her fixes, has been hospitalised for withdrawal symptoms, and misses her drug every day. 'Coralie' – not her real name – has gone through the same descent into hell as any junkie; except that her product can be found in a chemist store. “I've been addicted to prescription medicines for 20 years,” she says in a subdued voice.

Coralie, who is in her fifties, became addicted to the powerful painkiller fentanyl. Like another well-known medicine tramadol, it is an opioid, a family of drugs that has led to more than half a million fatal overdoses in the United States over the last 20 years. According to France's medicine safety agency the Agence Nationale de Sécurité du Médicament, some ten million French men and women – 17% of the population – have been prescribed these powerful painkillers. In Coralie's case, her family doctor prescribed fentanyl without warning her of the risks of becoming dependent, and gave her the most addictive, rapid-acting oral form using an applicator that is similar to a child's dummy.

This product enters directly into the gums to relieve the patient's pain as soon as possible but it also delivers a particularly addictive high. It is a method that is primarily used to relieve the sudden, intense and short-lived pain of people suffering from cancer.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Fentanyl was “wonderful” at the beginning, sighs Coralie. For the first time in sixteen years of seeking a medical solution to an auto-immune condition that causes terrible pains in her joints she had found a medicine that eased the pain and even gave her a brief moment of pleasure. But in the end it “ruined my life”, Coralie admits. “The physical, psychological and economic after-effects are too great. It's like I had a bit of respite but that was based on a dream, it wasn't real,” she says.

The very short-term effect of the drug is ill-suited to her daily suffering, and so very quickly the prescribed fentanyl doses proved insufficient. Her doctor increased the dosage again and again. This went on until her case was flagged by a doctor at the state health insurance system who had spotted the patient's huge prescriptions. Coralie was taking a minimum of 15 doses of 200mg a day, and sometimes up to 32.

Health insurance officials then refused to reimburse her for these drugs but after two decades of pain relief using opioids, Coralie could no longer do without it. So she continued to pay for them out of her own pocket. But her pharmacy bill had risen to nearly 800 euros a week. The 900 euros a month she received in disabled benefits was no longer enough and so she had to borrow the rest of the money.

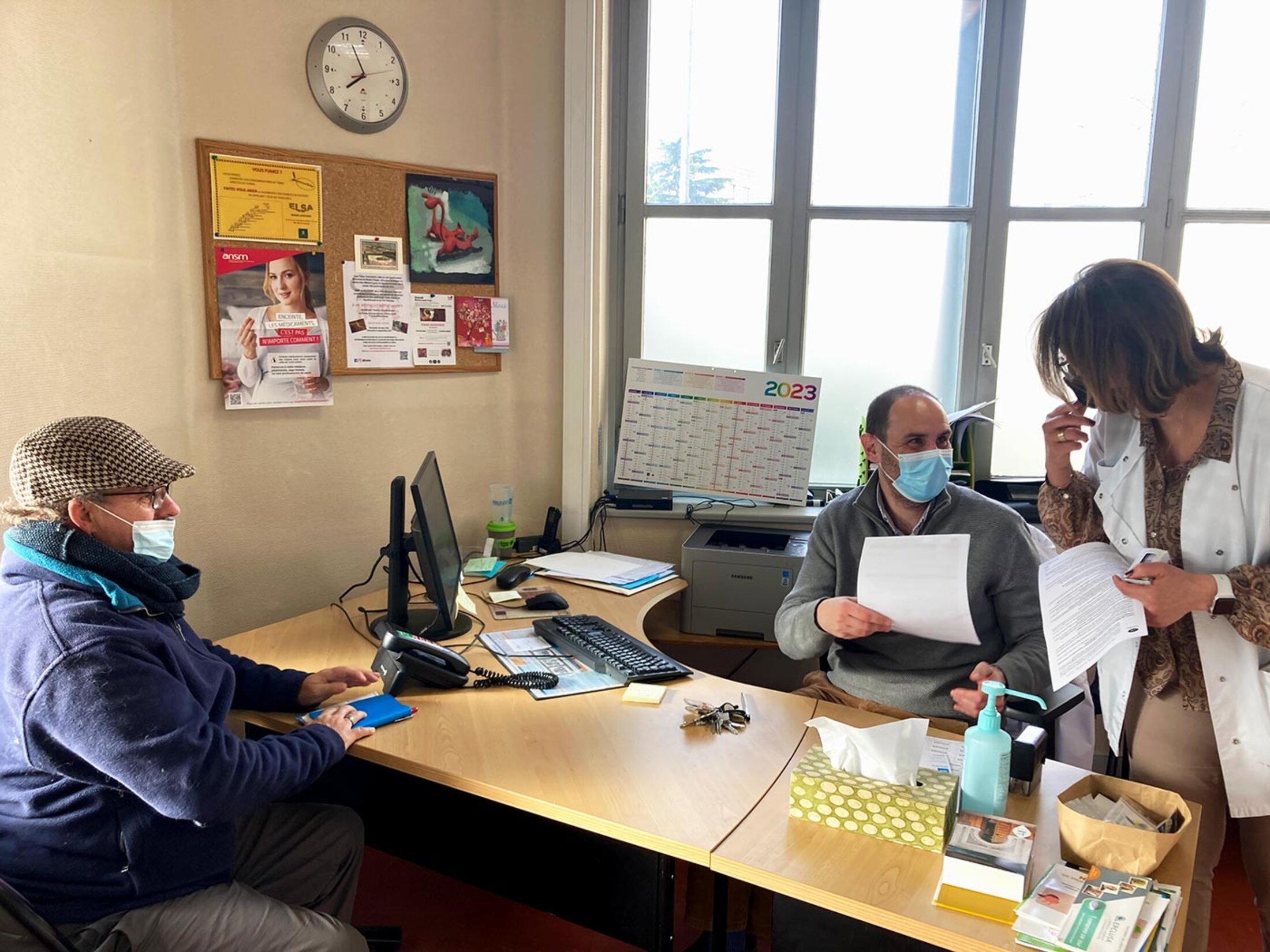

Meanwhile her family doctor no longer wanted to treat her and ended up referring her to the only clinic in France that specialises in treating addiction to prescribed medicines, the Centre Ressource Lyonnais des Addictions Médicamenteuses (CERLAM) at the Édouard-Herriot hospital in Lyon in the east of the country. This is a multidisciplinary unit inside the hospital's regular addiction clinic.

The pharmacist at CERLAM is Mathieu Chappuy. “The different forms of delivering the product make a difference,” he says. “There are patches with a prolonged effect in order to provide relief for longer at lower dosages, which limits the risk of addiction.”

I can't drive any more, the methadone makes me sleepy.

In November 2022 Coralie was hospitalised for ten days to wean her off fentanyl but the joint pains continued. That is precisely the problem for patients who have to endure chronic pain for their entire life. One solution is to gradually reduce dosages and then the patient is generally put on a substitute treatment such as methadone.

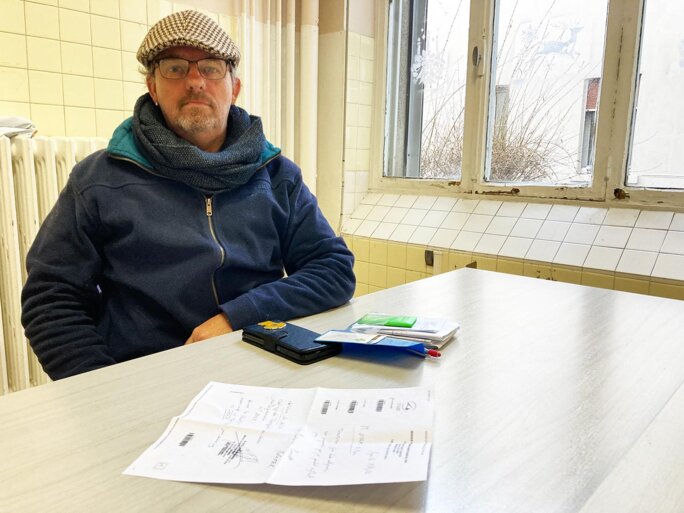

When Mediapart visited the centre on February 2nd Coralie had been booked in for a 11.30am appointment. She arrived swollen-eyed half an hour late from her home in the Monts du Lyonnais area just over 20 kilometres away, accompanied by a friend. “I can't drive any more, the methadone makes me sleepy,” explains Coralie, who is wearing a hoodie and is clad entirely in black.

Getting ready in the morning takes time. “I'm so bad when I wake up that I sometimes don't get to the loo. It's too painful to get up to go to the toilet before the substitute medicine starts to kick in, after 30 minutes,” she says. She has clearly not got over fentanyl and thinks about it all the time.

The cost of her substitute medicines is at least reimbursed by the state health insurance system. But opioids are not the only addictive drugs and so new prescriptions are introduced on a gradual basis. In Coralie's case the CERLAM centre is allowing her to have pregabalin alongside methadone. Pregabalin, which is sold by Pfizer under the brand name Lyrica, is increasingly being used by some people to get high rather than for its therapeutic qualities.

In 2009 Pfizer was fined for the mispromotion of this and other drugs. There are echoes here of the US TV series Dopesick which tells the story of the cynical methods of another pharmaceutical firm, Purdue Pharma, and its role in America's opioid crisis.

Black market and off-label use of prescriptions

Pregabalin was initially approved as a drug to tackle neuropathic pain – pain from the nervous system – and anxiety; it can now be bought on the black market in France for a handful of euros. In 2020 it was the most common name that the state health insurance administration found on falsified prescriptions. Indeed, in February 2021 it was deemed necessary to limit prescriptions of Lyrica and generic pregabalin brands to six months, using special secure prescription forms.

This tightening of the system by state health insurance officials did at least encourage hard-pressed doctors to question their automatic renewal of prescriptions. Since then the consumption of pregabalin in France has gone down by 18% in a year.

“Pharmaceutical promotion via pharmaceutical sales representatives can end up leading to bad information,” says Mario Barmaki, a doctor in the pain treatment centre at the private Médipôle Médipôle Lyon-Villeurbanne hospital at Villeurbanne near Lyon. “Laboratories invest billions of euros to market medicines, they don't give prominence to the appropriate precautions. I'm disgusted at the number of fentanyl and pregbalin prescriptions given outside their indicated use and with no warnings about their very addictive nature.”

The teams at CERLAM and the pain treatment centre at Villeurbanne refer patients to each other and exchange views in order to find the best balance in terms of drug dosage. On the February morning that Mediapart visited a very irritated patient had contacted the CERLAM addiction services. His pharmacist had been unable to provide him with his pregabalin-based syrup as it was out of stock – like other medicines in recent months, this drug has suffered from shortages too. Patients who have become dependent cannot wait and so the patient in question was prescribed the drug in tablet form. But pharmacist Mathieu Chappuy says that the syrup form is much more appropriate. “While tablets can be re-sold, that's not possible with the liquid version, and that limits the risk,” he says.

This form of the drug also allows for more individualised dosage that helps to get the right balance between relieving a patient's pain and the need to free them of addiction. “For patients who require pain treatment for life there is no off-the-shelf approach, you have to continuously tailor the help,” says Mario Barmaki.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

CERLAM only opened its doors in the summer of 2022 but is already swamped: around thirty people are being treated, with nine patients on a waiting list because there are no more places in the clinic. “Pain is the main reason why people go to see a family doctor. Only those doctors who started practising in the last ten years or so have been made more aware of it via courses on addiction integrated in their medical courses,” says Mario Barmaki.

Mario Barmaki and Benjamin Rolland, professor of addiction at CERLAM, pass on their knowledge to medical practitioners as part of a continuous training programme whose funding is independent of the pharmaceutical industry.

“General practitioners sometimes don't get more than seven minutes per patient in a consultation, they can't be a specialist in everything, and tackling the issue of addiction takes time. We provide information as much as possible and take over if need be,” says Benjamin Rolland. On February 14th France's health agency, the Haute Autorité de Santé (HAS), also published instructions online to help medical staff when treating people suffering from chronic pain.

Benzodiazepines: France is European runner-up

In terms of drug dependency, the other major risk comes from medicines prescribed to relieve anxiety, stress and insomnia such as Xanax, Lexomil, Valium, Rivotril, Ativan, Stilnox and so on. These are not to be confused with anti-depressants such as Prozac which, while not without side effects, do not provoke the same level of addiction. Though they are not supposed to be taken over the long term, the level of consumption of these anti-anxiety and sleeping pills from the benzodiazepine family is significantly underestimated.

In fact, France is the European runner up for such prescriptions, second only to Spain, according to French state medical insurance officials; an additional 3.4 million pills were dispensed between March 2020 and April 2021, during the pandemic.

And in 2022 the purchase of more than 93 million bottles of benzodiazepine pills was reimbursed by the state medical insurance system in France, at a cost of close to 100 million euros.

At the CSAPA addiction centre in Lyon one patient was swallowing so many benzodiazepine tablets that staff there could not believe their eyes: he was taking 300 a day. “Weaning him off was gradual and difficult, especially as no substitutes exist for benzodiazepines,” says Benjamin Rolland. “But it worked, he hasn't taken any more for a year.”

For general practitioners such addictions are often the hardest to manage because of their patients' constant demand for their sleeping pills or tranquillisers. Experts say this underlines the importance of knowing the underlying cause when prescribing anti-anxiety treatment; of warning the patients that it is only a temporary prop to help them deal with a particularly stressful episode in their life; and of making clear that it is for a maximum of 12 week, and that non-medicinal treatment, in particular seeing a psychologist, is often necessary as well.

Taking morphine to 'continue working at the factory'

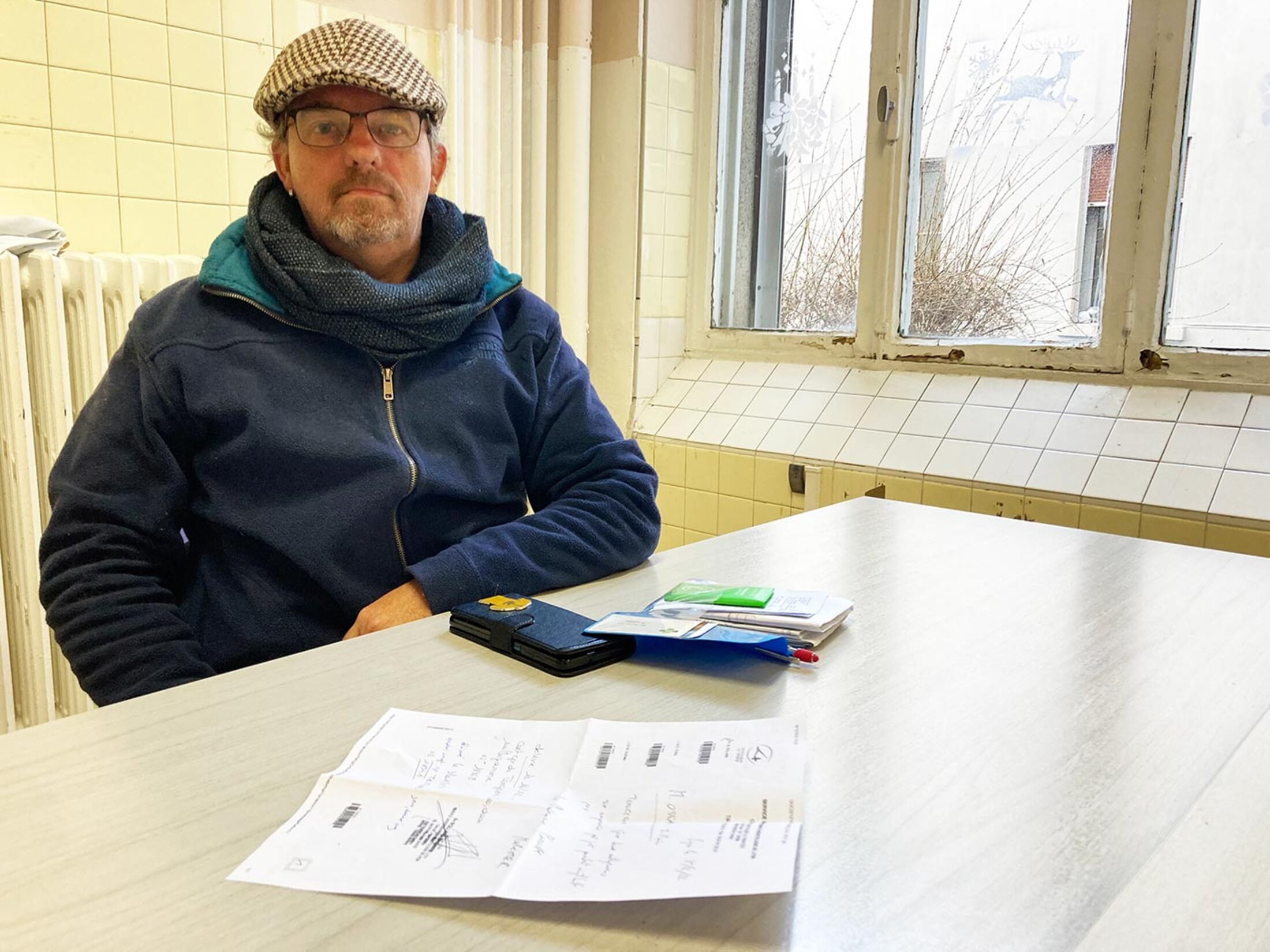

A taxi laid on by the health service brings Jean-Marie to the CERLAM centre. He, too, would not have been able to make it on his own from his village in the neighbouring département or county of Isère, which is an hour's drive away. Now that he is off the medication he comes every two months for a routine consultation. On this winter's morning the sky is clear and the patient is having one of his better days. “I'm like the weather. When it's fine, I'm well, I'm in less pain,” says the 53-year-old. “When the weather's bad the rheumatism lays me low, I stay on the sofa.”

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Jean-Marie was born with a spinal deformity and suffers from a degenerative disease, known as discopathy, which affects his intervertebral discs. He still receives a low dose of morphine substitute. The prescription is given on a special secure form used for narcotics and is limited to 28 days. However, his own doctor had given him his first morphine prescription back in 2012 with no warning about its potential impacts; the GP used it to replace the standard painkillers that were no longer helping and which were damaging Jean-Marie's stomach.

“All that to continue working at the factory,” says Jean-Marie now. Benjamin Rolland, who is sitting with the patient in his consulting room, says: “Powerful painkillers such as morphine and the opioids are supposed to provide relief on an ad hoc basis. Finding a long-term solution, such as [workplace] redeployment, with the workplace doctor would have been beneficial. It's an illusion to think that a person who has lower back problems of this kind can continue to carry heavy loads throughout the day.”

At first Jean-Marie experienced a honeymoon period with morphine. “When I was working morning shifts at the glass factory I would set off in the afternoons and go up the Chartreuse [mountain] peaks on my bike even if there was a metre of snow on the verge. People thought that I was crazy,” he says. He was certainly crazy about morphine. But his body quickly became used to the drug and he craved more, and this in turn made him more aggressive.

It was as easy as going to buy a stamp at the post office.

The doses were no long having enough of an effect on the factory worker. “I was getting up in the morning trembling, I was opening the drawer to take pills, sometimes 12 a day. I had something to eat all day! It stopped my appetite, I was just having one meal a week. I went from 70 kilos down to 40 kilos,” he recalls. Jean-Marie also lost most of his teeth, and just six have survived the malnutrition that he suffered.

“One Friday evening I ran out of morphine, I had no tablets, I thought it could wait until Monday. I spent a weekend from hell, I was as sick as a dog. It was then that I realised that I was an addict,” he recalls. “I'd never thought about it before as all I had to do was show my prescription to get it. It was as easy as going to buy a stamp at the post office.”

Having been laid off for being unfit to work, he now lives on his disability pension. His wife left him and his daughters worry about him. It is now Jean-Marie who warns them when they are prescribed painkillers.

He is in as much pain as ever. His logbook for the pharmacy is crammed with medical tests and prescriptions but he has learnt how to manage his suffering. And ultimately Jean-Marie feels much better than when he was being anaesthetised by morphine. On his better days he thinks about getting out; he has invested in the cycle of his dreams, a recumbent bike that he has adapted to make the pain more bearable.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter