When one compares it to the efforts of his two presidential predecessors, it was undoubtedly a skilfully-constructed success. Back in 2007 President Nicolas Sarkozy had sparked a scandal with his 'Dakar speech' – written by advisor Henri Guaino – in which he told his audience in the Senegalese capital that “the tragedy of Africa is that the African has not fully entered into history”. In the same city in 2012 the next French head of state, President François Hollande, promised that “the era of what one called Françafrique is over”, referring to France's traditional and controversial approach to the continent and its former colonies there. The rest of his presidency went on to prove that old practices and the old players have, too often, remained in place.

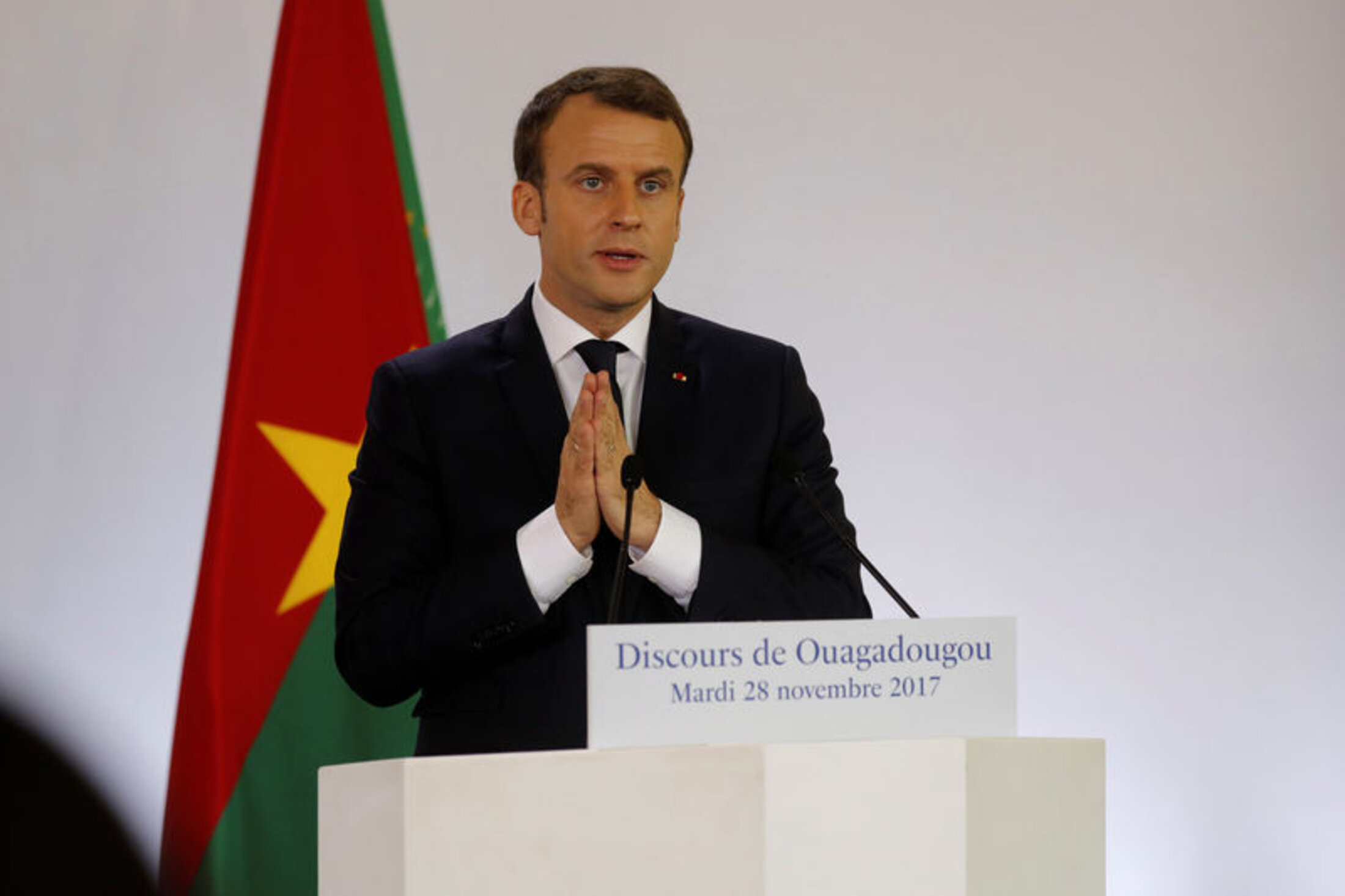

It was Ouagadougou rather than Dakar where the new French president, Emmanuel Macron, chose to deliver his 90-minute speech on Tuesday November 28th on Africa and France's policy towards the continent. Indeed, the first smart move was the choice of the capital city of Burkina Faso, a country which now has free elections and a democratic process since the rebellions that removed Blaise Compaoré in 2014, after 27 years of absolute rule. The second clever move was to visit Ghana on the last day of his three-day trip to Africa, as this English-speaking country has had a settled democracy for two decades or so and governments there hand over power without any problems.

For Emmanuel Macron's aim on his first African tour as president is to turn the page once and for all on 'Françafrique' and all that remains of it. It is no simple exercise as the French head of state found out for himself in Burkina Faso. France has been strongly criticised in that country precisely for having protected Blaise Compaoré in 2014 – he was an historic ally of Paris – and above all for having spirited him away to the Ivory Coast. In the same way there are still to this day answered questions about possible French involvement in the October 1987 assassination of the country's then-president Thomas Sankara, a charismatic leader both in Burkina Faso and of Pan-Africanism more widely.

In this, the year marking the 30th anniversary of his murder, Sankara's popularity has never been as great. Macron sought to defuse criticism by announcing on his arrival at Ouagadougou that all French documents relating to the Burkina Faso president's assassination would be declassified. “Every document that the Burkina Faso justice system would like to see will be opened and transmitted,” he said to a student who questioned him at the end of his speech at the University of Ouagadougou. That has also been a demand made by the International Campaign for Justice for Thomas Sankara (ICJS).

See here a recent Mediapart video interview, in French, on the legacy of Thomas Sankara.

Another smart move by Emmanuel Macron was to begin his speech in front of 800 students and current president Roch Marc Kaboré by quoting Sankara and his expression “daring to invent the future”. The French president added: “I was told that this was a Marxist and Pan-African lecture theatre and that's why I wanted to speak here.” From the start the president, whose long speech was listened to respectfully by the audience, wanted to turn his back on the past, this “past which must be allowed to pass”. Of course, he added, “the crimes of European colonisation are indisputable” but “our responsibility is not to get trapped in the past”.

To achieve that the 39-year-old French president played the 'new generation' card, highlighting his own relative youth to young people who constitute the majority of the African population; 70% of Africans are under the age of 30. “Like you I'm from a generation for whom one of the finest political memories is Nelson Mandela's victory,” he said. He was a 'young person' speaking to other young people. This approach served a double purpose: to remove the painful issues of the past and to differentiate himself, too, from old or very old African leaders who in some cases have been in power for decades.

Le changement sur un continent où 70% de la population a moins de 30 ans, ce n’est pas une option, c’est mathématique. pic.twitter.com/e8EEJEfVWK

— Emmanuel Macron (@EmmanuelMacron) 28 novembre 2017

“I haven't come to give lessons, we're not going to say to Africa what the rules are, what the rule of law is,” Emmanuel Macron insisted on several occasions. He even went so far as to say: “There is no longer a French African policy.” In other words the notion of Françafrique had been jettisoned to be replaced by state to state bilateral relations with the country's 54 countries. “Africa is neither a past burden nor a neighbour like any other: Africa is etched in France's identity,” he added. Obviously large sections of the presidential speech very quickly went on to contradict such fine stated intentions, as what followed was a policy specially geared to French-speaking Africa.

So, after the appeals for young people to take their destiny in their own hands, to fight for pluralism and democracy, for education and for gender equality, after urging a fight against “religious obscurantism” and a united front against “extremism”, and for Africans to take part in the fight against climate change, some very practical difficulties emerged.

Support for despised regimes

The first difficulty is the paradox of appealing to young people while at the same time paying homage to regimes that are despised, sometimes authoritarian and often corrupt but which are firmly in power. Thus during his speech President Macron paid tribute to the president of Chad, Idriss Déby, who has been in power for 27 years, the president of Niger Mahamadou Issoufou, in power since 2011, the king of Morocco, Mohamed VI, and the new strongman in Saudi Arabia, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman. However, the French head of state held back from citing the name of the president of Mali Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta, aged 72 and his corrupt regime, which has nonetheless been propped up single-handedly by France since 2013. Nor did Emmanuel Macron mention 84-year-old Paul Biya, the president-dictator of Cameroon for 35 years and a close ally of Paris, nor Ali Bongo, the inheritor of the old Françafrique legacy in the Gabon.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

The second difficulty is development aid. Emmanuel Macron reminded his audience of his commitment to bring the level of France's overseas aid up to 0.55% of GDP by the end of his presidency, and to “change methods” to make it more effective. But nothing more. This aid often gets lost in the back channels of corruption or is handed over in exchange for public works contracts for several large French groups, or sometimes simply for political services rendered. “France will no longer invest so that large groups can take part in transactions involving generalised corruption,” said President Macron.

But this remains a major factor in events on the ground in Africa. Large French groups such as Total, Bolloré, Bouygues and Vinci are regularly criticised for their methods. Again, apart from the ritualistic good intentions uttered by every president, there was nothing new on this front. Oxfam later criticised what it called the “missed opportunity of Ouagadougou”. Oxfam France said: “It doesn't stack up! Emmanuel Macron committed himself to increasing aid by 6 billion euros between now and 2022, yet for the moment the 2018 budget provides for a minimal increase of only 100 million euros.”

The third difficulty is France's military stalemate in the war against terrorism in the Sahel, the area of semi-arid land below the Sahara that includes Mali. Emmanuel Macron made a tacit reference to this. Now that the French-led anti-insurgency Operation Barkhane has become, since October, a G5-Sahel operational force it is “vital to obtain the first victories”, said the president. In addition to France, G5 brings together the military resources of five countries in the region, Chad, Niger, Mali, Burkina Faso and Mauritania. So far it has been unable to halt the progress of terrorist groups that have become better and better organised. Almost five years after Operation Serval was launched by France in Mali to oust Islamist terrorists, military powerlessness and political inertia have combined, meaning that peace remains elusive.

This latest reinforcement to the existing presence of the French military in the majority of French-speaking Africa has faced strong criticism among local public opinion. Macron repeated that the aim is to pass the baton to “regional organisations”. The problem is that these organisations are not ready and that political processes have broken down. That is the case with Mali where President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta has held off from any negotiations with Tuareg forces in the north of the country. “I tell you, I'd rather send you a lot fewer soldiers. You owe just one thing to French soldiers, to applaud them. They are there at your soldiers' side, soldiers from the region who are combatting jihadism,” the president replied to one student when questioned on this subject.

Vous ne devez qu'une chose pour les soldats français : les applaudir ! pic.twitter.com/JqBj4fp39P

— Emmanuel Macron (@EmmanuelMacron) 28 novembre 2017

The fourth difficulty is a speech which constantly ran up against the realities of France's policy on migration. The French head of state once again condemned as a “crime against humanity” the scandal of the trafficking of Sub-Saharan migrants in Libya who are sold as slaves. “It's a tragedy that we have allowed to prosper,” the president acknowledged. He promised a “Euro-African initiative” to take down the terrorist networks and arms and weapons trafficking. President Macron also announced “massive support for the evacuation of persons in danger in Libya”. He also called for a “step change in the level of mobilisation, that's our historic duty”.

That issue was discussed on Wednesday, November 29th, in Abidjan in the Ivory Coast during a European Union-African Union summit. But France in no way intends to review its cooperation with the Libyan authorities and the funding put in place, as Macron's prime minister Édouard Philippe made clear in a recent interview with Mediapart (see it in French here). France does not want to open its borders a little more or widen the scope for attaining the right to asylum, quite the opposite. In the end, France says, it would come up against both other member states and the European Commission on this issue.

The fifth difficulty is that as a result of wanting to defend himself against the charge of giving lessons, the French president at times ending up delivering an assured academic lecture that sometimes overreached itself a little. Speaking in Hamburg last July the French president caused a row when, speaking about Africa, he said that “when some countries still today have 7 to 8 children per woman, you may chose to spend billions of euros there but you won't stabilise anything”.

In Ouagadougou Emmanuel Macron once again launched into a lecture on demographics. “Seventy percent young people, that's Africa, yes that's an opportunity. But seven or eight children per woman: are you really sure that each time it's the girls' choice, the women's choice? Nowhere in Africa do I want a girl get married at 13 or 14 and start to have children,” said President Macron. Back in July the historian Françoise Vergès had already responded on this issue: “As soon as a man in power gets involved in saying how many children women should or shouldn't have, alarm bells should start ringing.”

There were also overtones of an academic lecture in President Macron's calls to defend the French language at a time when English continues to make inroads in these countries because it offers more professional opportunities or opportunities for migration to countries that are far more open. And in those odes to African culture and its heritage that are still largely appropriated by the former colonial powers.

As a 'young' man facing young people, Emmanuel Macron undertook to take questions from several students in his audience. It was certainly an unprecedented act for a French president visiting Africa. Here, too, the French head of state would have noticed that clever rhetoric could not mask the extent to which France's image had been damaged and how some of its politics rejected. In fact the 'youth of Africa' themselves appear determined to turn the page. And for real.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter