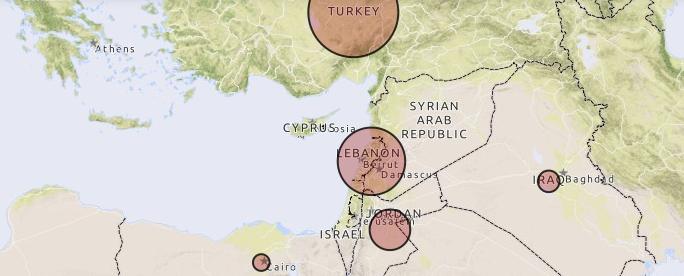

The Syrian civil war, which began in 2011, has caused one of the greatest mass exoduses of people the world has seen since the end of World War II. The counter on the website of the UN Refugee Agency the UNHCR tells its own story: so far more than 3.8 million Syrians have fled their country. This is on top of the 6.5 million other Syrians who have been forced to move to other parts of the country to escape the conflict. The countries most affected by the exodus have been Syria's immediate neighbours. Around 1.6 million Syrians have sought refuge in Turkey, 1.2 million in the Lebanon, 621,000 in Jordan, 235,000 in Iraq and 136,000 in Egypt.

The hospitality of these neighbours has its limits, however. In the Lebanon, where Syrian immigrants now represent a third of the population, the authorities have started imposing a visa system to limit how long people stay. The majority of crossing points across the border – some of which are controlled by Islamic State – have been closed. Though that does not stop people from leaving, providing they have the money.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Indeed, threatened by the deadly fighting, entire families have sold up all their belongings, down to the last ounce of gold, in the hope they can rebuild their lives elsewhere. Given that legal means of escaping are available only to a minority, Syrians are now taking all kinds of risks to escape. In 2014, for the first time, Syrians, along with escapees from another war-torn country, Eritrea, made up the majority of the 207,000 people who crossed the Mediterranean on fishing boats or cargo ships in search of refuge.

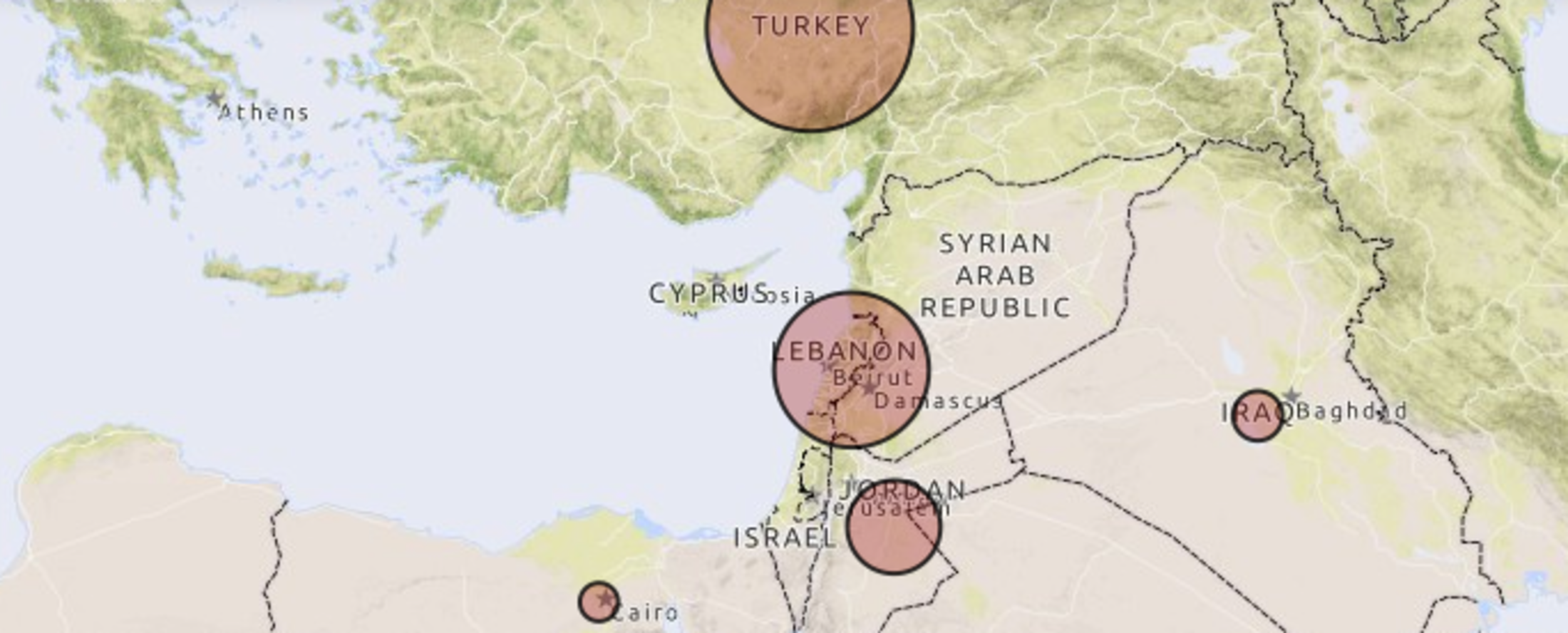

It is against this explosive backdrop that France’s refugee and stateless persons protection agency, the Office Français de Protection des Réfugiés et Apatrides (OFPRA), recently published its provisional figures relating to its activities in 2012. And, curiously, they show a decrease in the number of asylum demands made in 2014 compared with 2013, the first such drop after six consecutive years of increases. It is true that, at just 2.6%, it is a small fall, with 64,536 cases being examined last year compared with 66,251 the year before. But it is nevertheless hard to understand, given the geopolitical context.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

For in the same period the number of requests for asylum made in member states of the European Union as a whole rose by 25%. In Sweden, for example, a country with a seventh of the population of France, more than 80,000 people sought asylum in 2014, with 40% of them Syrians. The authorities there expect the number of applications to jump to 105,000 in 2015. There is a similar trend in Germany where more than 202,000 people applied for asylum in 2014, a 60% increase in a year. According to the German minister of the interior, Thomas de Maizière, these figures included 41,000 Syrians.

The contrast with the situation in France is striking; in 2014 some 3,100 Syrians were granted refugee status. This figure was up on previous years – since the conflict began around 5,000 Syrians have been given asylum by the French authorities – but the numbers are small compared with Sweden and Germany. Last year, for example, Germany announced that it was increasing the guaranteed number of Syrian asylum seekers it would accept to 20,000.

The paradox of the low French figures is that not only do they come at a time of continuing mass migration, but also just as the government in Paris itself lauds its credentials as a destination for those seeking refuge. In comments backing his own asylum law proposals, French interior minister Bernard Cazeneuve told the National Assembly in December 2014: “A France that, in 1789, rose up against arbitrary power and proclaimed to the world its ideals of freedom and equality cannot shirk its responsibility when there are those knocking at its door who trust it to protect them against injustice, against oppression and against barbarism.”

Enlargement : Illustration 3

It is true that the success rate of asylum applications rose in 2014, from 24.4% to 28%, meaning that while fewer cases were examined, relatively more applications were accepted. (See Mediapart's recent video interview here, in French, with OFPRA's director general Pascal Brice.) In total 14,489 people were granted refugee status in France in 2014, against 11,371 in 2013. Almost all Syrian applications were successful.

As for the fall in the number of asylum seeker demands, that can in part be explained by the sharp fall in the number of applications from the Balkans, Kosovo in particular, Sri Lanka and Russia. But how can one explain the fact that there are not far more asylum seekers from Eritrea and Syria? Is it because France is no longer recognised as a place of welcome? Does the asylum system work so badly that it discourages applicants? Do the refugees simply prefer to go elsewhere? Or are they being prevented from making their applications to France in the first place?

Most humanitarian visa applications rejected

According to interviews carried out with potential asylum seekers, many of them only stay in France for a short period. For some this is simply because they are using France simply for transit, and want to get to another country where they have family or friends. Generally English speakers, such individuals think they have better economic prospectives in north European countries, where they have professional networks. Others, in particular those who travel via the northern French port of Calais, mostly Eritreans, Sudanese and Somalians, point to the police harassment they suffer to explain their hesitation about staying in France.

“The traffickers can encourage them to continue their journey to extort even more money out of them,” says Pascal Brice, who has himself been to visit the “jungles” - the name for the migrants' squats and camps in and around Calais. Brice also admits that the nature of the asylum system itself is an issue. The accommodation centres are full to the point that not all asylum seekers are able to find a place to stay. Moreover, the length of time it takes for cases to be heard – up to two years – discourages potential applicants from making a request in the first place.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

To boost its “effectiveness”, OFPRA has recently hired 55 extra officials as part of an internal reorganisation that has been going on for two years. Meanwhile the ministry of the interior has promised to create 5,000 extra accommodation places between now and 2016. But the key issue remains access to rights. A branch of France’s immigration and integration service, the Office français de l’immigration et de l’intégration (OFII), has been opened in Calais to inform people better about the protection they can receive in France. However, the migrants do not always see the distinction between the staff at this state body, one of whose tasks is to inform them about returning to their country, and the police.

The obstacles are not just technical – they hide a flagging political will. If they had the choice the refugees would prefer to travel legally and safely, in other words with a visa. They only undergo their dangerous journeys without documentation because the consulates of European nations based in countries close to the Syrian conflict only hand out entry and short-stay visas very sparingly. French consulates receive large numbers of requests for humanitarian visas, most of which are rejected. The French foreign ministry says the precise figures are not available. The result is that the majority of those 3,100 Syrians who were granted asylum in 2014 had to make their own way to France and make their request in person.

The ministry of foreign affairs insists there are other possibilities for would-be asylum seekers. It points to a special programme put in place to reach out to families of Syrian refugees in neighbouring countries. These people are 'pre-selected' by the UNHCR and are chosen because they are either in an extremely vulnerable situation or because they have links with France. But the numbers involved are small; 500 people in 2014 and a similar number expected in 2015. The ambition of this scheme – under which the families get accommodation and 'integration' courses – is thus out of step with the government’s own official declarations. It also pales alongside the 20,000 guaranteed places offered by Germany.

There are several ways the government could back up its words with actions. In addition to changing the whole way the asylum system is run – something envisaged in the legislation going through the French Parliament – the government could, given the seriousness and urgency of the situation, start by handing out more humanitarian visas and increasing the number of people who benefit from its special programme. It could also virtually immediately remove the logjam that it itself discreetly put in place after the start of the Syrian war; namely the obligation to have an airport transport visa (known as a VTA for short in French) which stops Syrians in transit at airports in France from claiming asylum there.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter