For the captains of merchant ships navigating the Mediterranean Sea between the waters off the coast of Libya and the Strait of Sicily, the passage, which for giant container ships and oil tankers can last between 36 and 48 hours, has become a nightmare.

Their crews are constantly on the alert for boats carrying migrants, vessels in peril which they are not certain to be able to help, nor what the risks are should they do so, not to mention the risks if they do not. Such lifesaving missions are complicated and dangerous, and they have not all ended well – some concluding in drowning tragedies, such as that in which an estimated 800 people drowned off Libya on April 19th – and when they are successful there is the dilemma of what to do with the sometimes hundreds of migrants taken on board.

The diversions of merchant ships for lifesaving operations have become so numerous – about 1,000 such incidents were recorded over the past year and a half – and so problematic that some captains could be tempted "to look the other way" warned Captain Hubert Ardillon, president of the Confederation of European Shipmasters’ Associations (CESMA), the umbrella organisation representing 17 merchant shipping associations across 14 European countries. “We have the feeling of being taken hostage by the situation,” Ardillon told Mediapart.

Between Friday May 29th and Sunday May 31st, several merchant ships from Ireland, Germany and Denmark were required to help British, Italian, Belgian and Maltese warships in search and rescue (SAR) missions coordinated by the European Union border control agency Frontex, in the framework of its Operation Triton.

According to statistics provide by the Italian authorities, who have the operational command of Triton, merchant vessels were responsible for rescuing some 42,000 migrants attempting to cross the Mediterranean towards Europe in 2014, while between January and April this year the number rescued by merchant ships was 3,809. The commercial ships are duty-bound to intervene under the unconditional maritime law requirement to save lives in peril at sea. “No captain places that principle into question,” said Ardillon.

The members of his confederation are preoccupied by the risks taken by their crews in SAR operations. At the last general assembly of the CESMA, held in the Italian coastal city of Viareggio between May 15th-16th, the issue was at the centre of discussions. “That’s new,” said Ardillon. “For years we hadn’t asked such questions. We had other concerns. There is no shortage of danger zones around the world, such as off the coast of Somalia with the pirates. But the number of sinkings since last autumn in the Mediterranean requires us to react. Our members find themselves powerless in face of the situation.”

“The passage via the Strait of Sicily is inescapable,” Ardillon explained. “To go from the Suez Canal to the Atlantic seaboard it’s difficult to avoid it, other than making a diversion around South Africa, which considerably lengthens the journey.”

Philippe Martinez is the captain of a French high sea tug, the Léonard-Tide, which carries supplies to oil rigs off the coast of Libya and Malta. Last year his boat rescued a total of more than 1,800 migrants in eight different incidents. Interviewed by the French media, he spoke of the perils of such operations for both the migrants and inexperienced crews. “When they saw us, they all came to our side,” he explained in an interview with news channel BFMTV last month. “With the movement of the crowd it made the boat dip enormously. In fact you must keep at a distance and speak to them beforehand. Give them indications, tell them not to move, because they are so afraid. They are so scared that when they see someone coming to their rescue they jump on them.”

“In one of the crafts, a sort of small fishing boat in wood of 12-13 metres, there were 684 people and three dead,” he said. “It was completely mind-blowing. There were migrants all the way to the masts, in the hold, the machine room. Wherever there was a square centimetre free, somebody was there.”

Martinez added that the migrants’ boats he came across “had neither flares, nor radar, nor radio, nor lifejackets, nothing of anything”.

On March 31st this year, representatives of the merchant maritime industry and seamen’s unions issued a joint statement addressed to EU heads of state in which they made clear that crews could no longer cope with the rhythm of the SAR missions.

“We believe it is unacceptable that the international community is increasingly relying on merchant ships and seafarers to undertake more and more large-scale rescues, with single ships having to rescue as many 500 people at a time,” wrote Thomas Rehder, president of the European Community Shipowners’ Associations (ECSA), Eduardo Chagas, secretary general of the European Transport Workers’ Federation (ETF), Masamichi Morooka, chairman of the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS) and Dave Heindel, chair of the Seafarer Section of the International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF). “Commercial ships are not equipped to undertake such large-scale rescues, which also create serious risks to the safety, health and welfare of ships’ crews who should not be expected to deal which such situations. […] In the short term, we therefore feel that the immediate priority must be for EU and EEA Member States to increase resources and support for Search and Rescue operations in the Mediterranean, in view of the very large number of potentially dangerous rescues now being conducted by merchant ships; a situation which we believe is becoming untenable.”

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), a number of maritime companies, in face of the potential financial losses incurred by diversions for SAR operations, have begun rerouting their ships, while some boats refrain from transmitting their positions at sea.

SAR operations in the Mediterranean around the Strait of Sicily are managed by the Maritime Rescue Co-ordination Centres in Italy and Malta, who redirect nearby shipping to the locations of the SOS alerts they receive. Captain Bertrand Derennes is president of the French ship captains’ association AFCAN (l’Association française des capitaines de navire). His oil tanker was recently instructed to divert its route to help the Italian navy with the rescue of some 300 people, including 180 women and children, crossing the Mediterranean in a fishing boat. Derennes’ ship was to serve as a shield for the rescue by positioning it to reduce the strong sea swell. “My mission stopped there, fortunately” he said. “I was not equipped to receive 300 people. These situations are dangerous for everyone, the migrants and us. The captains regard this as a hostile situation.”

The reluctance of merchant ship captains to become involved in the SAR missions is not, their representatives insist, for reasons of the financial losses such diversions can incur, but because their crews are rarely skilled for such dangerous manoeuvres. “We are neither trained nor equipped,” said Hubert Ardillon, of the Confederation of European Shipmasters’ Associations. Ardillon was for 30 years captain of a supertanker (Very Large Crude Carrier), until his retirement from active seafaring in 2011, and has himself been involved in the rescue of a small dinghy carrying migrants when navigating between Mauritania and the Canary Islands.

Merchant ships pick up where Triton falls short

Ardillon said one problem for merchant vessels is that of being able to identify a craft in jeopardy. “With a heavy sea, especially at night when the crew on the bridge is reduced, you run the risk of missing the boat on the radar, especially if he doesn’t have lights, and above all if the people smugglers haven’t switched on the AIS [automatic identification system],” he explained.

But when a craft has been identified, and a merchant ship attempts a rescue of its occupants, Ardillon said the risks can be immense for both crew and migrants, as cited by French high sea tug captain Philippe Martinez. Boats have been overturned when migrants rush to one side for rescue, some fall into the sea attempting to grab a rope. In many cases, they are severely fatigued by days at sea in cramped positions without sufficient water or food. “You send down the gangplank, but people are exhausted,” said Ardillon. “How do you go about bringing up women, children, the sick and the old? Nothing is prepared. The size of our boats is a handicap. The freeboard [editor’s note: the distance between the waterline and the deck] varies between eight and ten metres when fully loaded. Unloaded, you reach 20 metres. With the swell, climbing up is virtually a mission impossible.”

Other difficulties, he said, include the use of lifebuoys. “There are only about 20 on board,” explained Ardillon. “Do you take the risk that people will fight to get hold of them? You could lower down a lifeboat, with a capacity of between ten and 20 people, but you have to make return trips if there are several hundred shipwrecked. In what order do you take people onboard? ”

Ardillon stresses also the problem of rescuing large numbers of migrants: “We are not equipped to receive so many people. The crew is made up of about 20 people. The meals, drinking water, sleeping berths, toilets, everything is prepared for that many. Above that, it’s complicated. What do you do with the sick? With pregnant women? Except on cruise ships, there is no doctor. When I navigated, I was considered to be the doctor, with one week’s training every five years. I [had] the basic knowledge, a pharmacy for 22 people, but in the case of hyperthermia I don’t know what to do […] There is insufficient space inside. On the deck of a chemical tanker, the valves ooze toxic material.”

“It’s no small matter to embark two or three hundred people for 20 sailors," added Ardillon, citing the average crew of the larger merchant ships. "The power relationship is unequal. How do you contain these people if they fight among themselves, or if they seek to take control? Captains aren’t armed. We have nothing to defend ourselves with. What do you do if things take a turn for the worst? You don’t, per se, know what people’s intentions are.”

In fact, there have been no reports over recent years of migrants taking control of a ship they were rescued by. But the concerns are fuelled by fact and rumour; there is a fear that terrorists may be among the migrants or that migrants hoping to land in France might refuse to disembark in Italy. “If a ship was travelling to a destination not planned by the Maritime Rescue Co-ordination Centre, the shipwrecked [migrants] would become clandestines and we captains could be prosecuted for helping [their] illegal passage,” added Ardillon. International law prohibits the return of migrants to a destination where their lives would be in danger, which means that disembarking rescued migrants in Libya, even if a Libyan port was closest to the rescue point, is not an option.

The principal demand of the representatives of merchant navy captains is that they should not face legal consequences if they judge that a rescue operation is too dangerous to become involved in. “A difference must be made between providing assistance while keeping a distance and taking people onboard,” said Ardillon.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

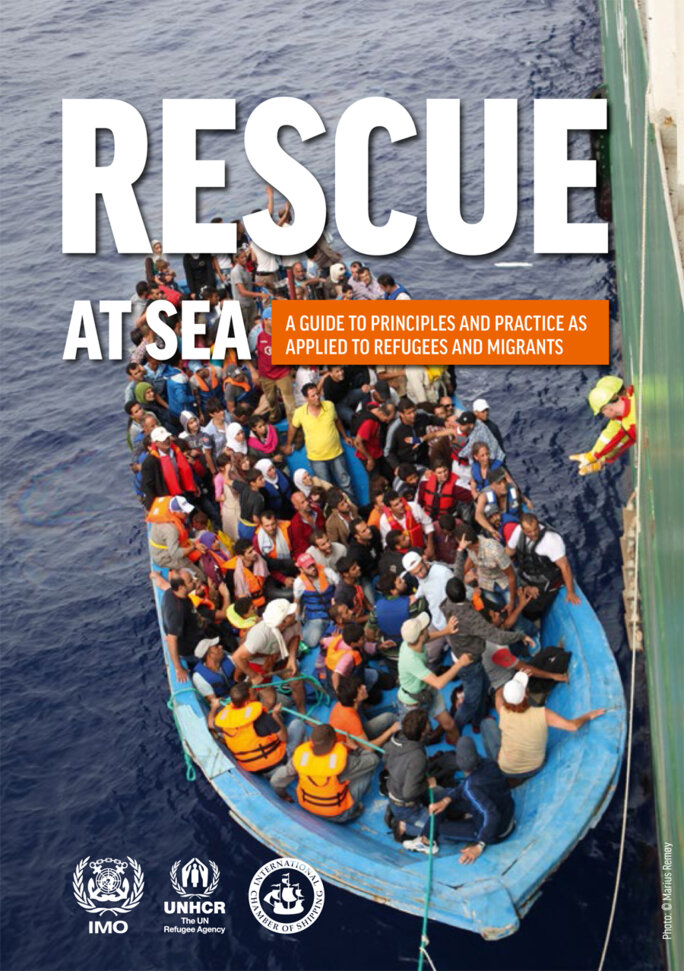

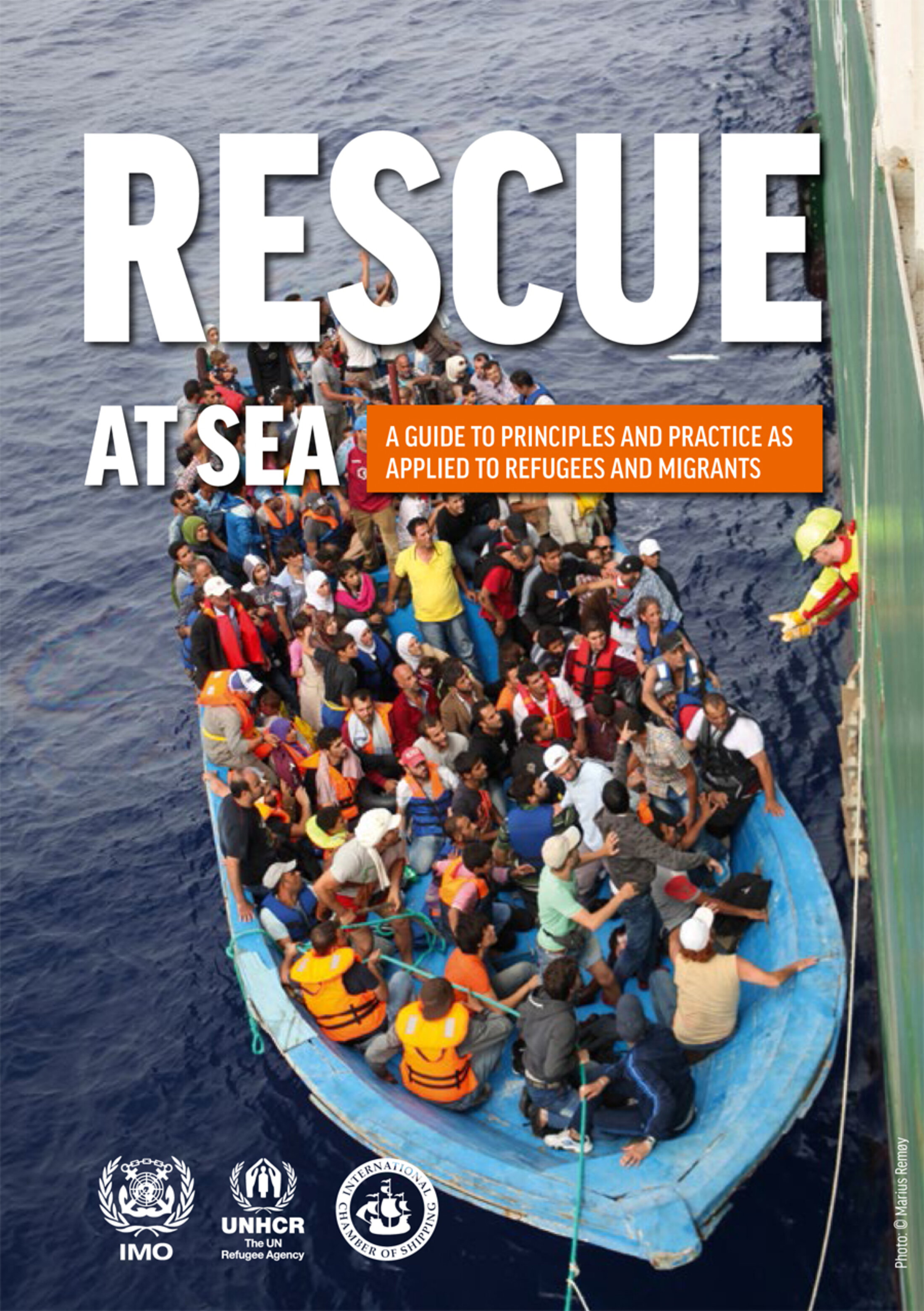

The International Maritime Organization (IMO), the International Chamber of Shipping (ICS), and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) have jointly produced a revised version of their guide ‘Rescue at Sea, A guide to principles and practice as applied to refugees and migrants’ (available in six languages and which can be downloaded here). The IMO’s presentation of the guide, which is distributed to merchant navy vessels by the organisation’s member states, warns: “It is likely that 2015 will reach a record high for illegal migration at sea, putting lives at risk and placing a huge strain on rescue services and on merchant vessels. The age-old principles of rescue on the high seas are being stretched to breaking point.”

The guide, which is also addressed to ship owners and insurance companies, underlines that the rules of the 1974 Safety of Lives at Sea (SOLAS) convention requires the “master of a ship at sea which is in a position to be able to provide assistance, on receiving information from any source that persons are in distress at sea, ... to proceed with all speed to their assistance, if possible informing them or the search and rescue service that the ship is doing so”. But it also stresses that the SOLAS convention and the 1979 International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue requires state authorities to “ensure that necessary arrangements are made for distress communication and co-ordination in their area of responsibility and for the rescue of persons in distress at sea around its coasts”, which is in part aimed at avoiding the situation where a ship is left without a reasonably close disembarkation port.

In a report published in April this year, entitled ‘Europe’s sinking shame, the failure to save refugees and migrants at sea’, Amnesty International also highlighted the crisis for merchant shipping. “Large scale rescues at sea, sometimes of hundreds of people at a time, pose significant challenges to commercial ships and their crews,” it said. “Even large ships often have small crews of some 20 people, and have provisions and accommodation only for them. For the crew, taking care of the immediate needs of scores of distressed people is strenuous and means many extra hours, lack of sleep, and significant health and safety concerns.”

“[...]While it is essential to the effective working of the search and rescue regime that commercial ships continue to uphold their obligations to assist those in distress, European governments have a responsibility to ensure that commercial ships are not burdened by unnecessary risks and costs,” the report also advised. “European governments should in particular ensure predictable and rapid disembarkation at a place of safety of those rescued, with minimum deviation from the intended route of the ship. Most of all, European governments should take their responsibility and set up a search and rescue system whereby appropriate national vessels and aircraft are able to perform the vast majority of operations.”

On April 19th, an estimated 800 migrants drowned after their boat sank close to Libyan waters. According to the Italian authorities, whose rescue operation found 27 survivors, the boat collided with a Portuguese merchant ship, the King Jacob, which had come to its rescue and capsized after its occupants rushed to one side of the unstable vessel. Italian media reported that it was the fifth time the King Jacob had been involved in rescuing migrants in the area.

Four days after the tragedy, European leaders met at an emergency summit in Brussels where they committed to sending more naval backup and funding for Operation Triton. But the following day, the International Chamber of Shipping, the merchant shipping industry’s principal representative association, issued a statement in which its general secretary, Peter Hinchcliffe said: “We understand that the resources of Triton can be deployed in international waters when called upon by national Maritime Rescue Coordination Centres, but it remains highly doubtful whether they can rapidly reach areas near the Libyan coast, where most incidents tend to occur.”

-------------------------

The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse