The tragic plight of young migrants, who are particularly exposed to the many dangers all migrants face along the long route to exile, is the subject of a shocking joint report published this week by the United Nations bodies UNICEF and the International Organization for Migration (IOM).

“For children and youth on the move via the Mediterranean Sea routes to Europe, the journey is marked by high levels of abuse, trafficking and exploitation,” reads the introduction to the report, entitled “Harrowing Journeys” and published on Tuesday, which draws on interviews with about 11,000 migrants under the age of 25, many of them minors. “Some are more vulnerable than others: those travelling alone, those with low levels of education and those undertaking longer journeys.” The most vulnerable, it underlines, are those from sub-Saharan Africa.

Whether travelling with their parents or on their own, their young age offers no protection against the many hazards that line the treacherous route north to escape war or extreme poverty. Some make it to Europe, others are separated from their families along the way, some disappear without trace, while others die crossing the Sahara desert or the Mediterranean Sea.

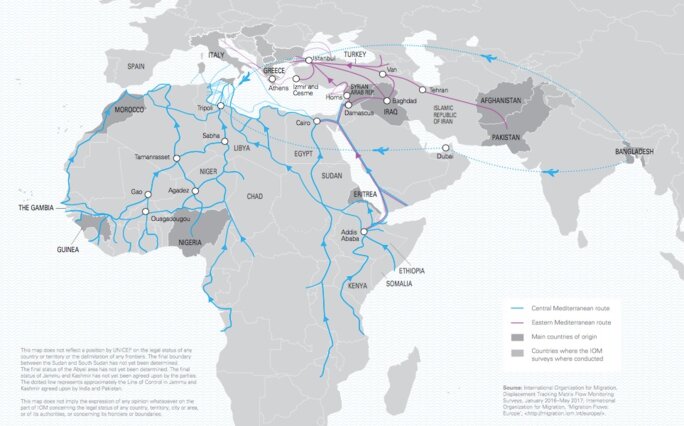

A factsheet conjointly published in April this year by UNICEF, the IOM and the office of the UN High commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that in 2016, more than 100,000 minors were among migrants who arrived in Greece, in Italy, Spain and Bulgaria. More than 33,800 of them were unaccompanied or had been separated from those they began their journey with. Most of them came from Syria, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iraq crossing to Europe from Turkey via the Aegean Sea. The numbers following that route depleted considerably after the agreement reached in March 2016 between the European Union and the Turkish government which began preventing the clandestine crossings. As a consequence of the decision by countries in the Balkans to close their borders, many thousands of minors became trapped in holding camps in Greece, living in often squalid conditions.

The most recent figures for 2017, published in June by UNICEF, the IOM and the UNHCR, show that the largest number of migrant minors (and all major migrant movements) were heading to Europe via Libya, crossing the Mediterranean to Italy, a sea crossing that, since 2014, has become the most treacherous of any migrant route in the world. Most of the migrants using that path are from Nigeria, Guinea, Gambia and the Ivory Coast. According to the UNICEF-IOM report published this week, more than three-quarters of those interviewed who had taken the route complained of mistreatment, both by the traffickers supposed to help them to reach Europe and in Libyan detention camps where many complained of beatings, and of being trapped in conditions akin to slavery, again notably in Libya.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

The migrants’ route through Libya is overseen by different militias whose treatment of their charges is notorious, with many reports of sexual exploitation of female migrants and of males given forced labour duties. Aimamo, a 16-year-old who fled Gambia along with his twin brother, Ibrahim, was interviewed after arriving in a refugee camp in Italy. In lieu of payment for their journey to Europe they had agreed to work for free for a while in Libya. “Along with 200 other sub-Saharan Africans, they spent two months working on a farm – and enduring beatings and threats,” the report said. “ When work was done for the day, they were locked in to prevent them from escaping. After that ordeal, getting on the flimsy inflatable raft that took them to Italy was a relief.”

It cites the case of 17-year-old Sanna, also from Gambia, who said he had been ready to take on any work in Libya to fund his remaining journey north. “But the Libyans sometimes refused to pay us,” he told the UN officials, “and if we discussed it with them, they would bring a gun. You cannot do anything; we were like slaves.”

Another 17-year-old Gambian, Alieu, who is now seeking asylum in Italy, recounted the atmosphere of violence he witnessed in Libya: “Everybody has a gun. Small boys – that’s what really surprised me – old men. Everybody has an AK-47. Every day you hear boom-boom, boom-boom.”

The report highlighted the case of Lovette, a 16-year-old Nigerian girl who travelled through Libya with a group of other migrants. They were arrested and detained for not having official papers. “Packed into an overcrowded cell, the women and girls were fed only three days a week, and beaten by guards if they complained,” the report said. “Lovette and her cellmates broke down a door to escape. They immediately fled and got on a boat to Italy.”

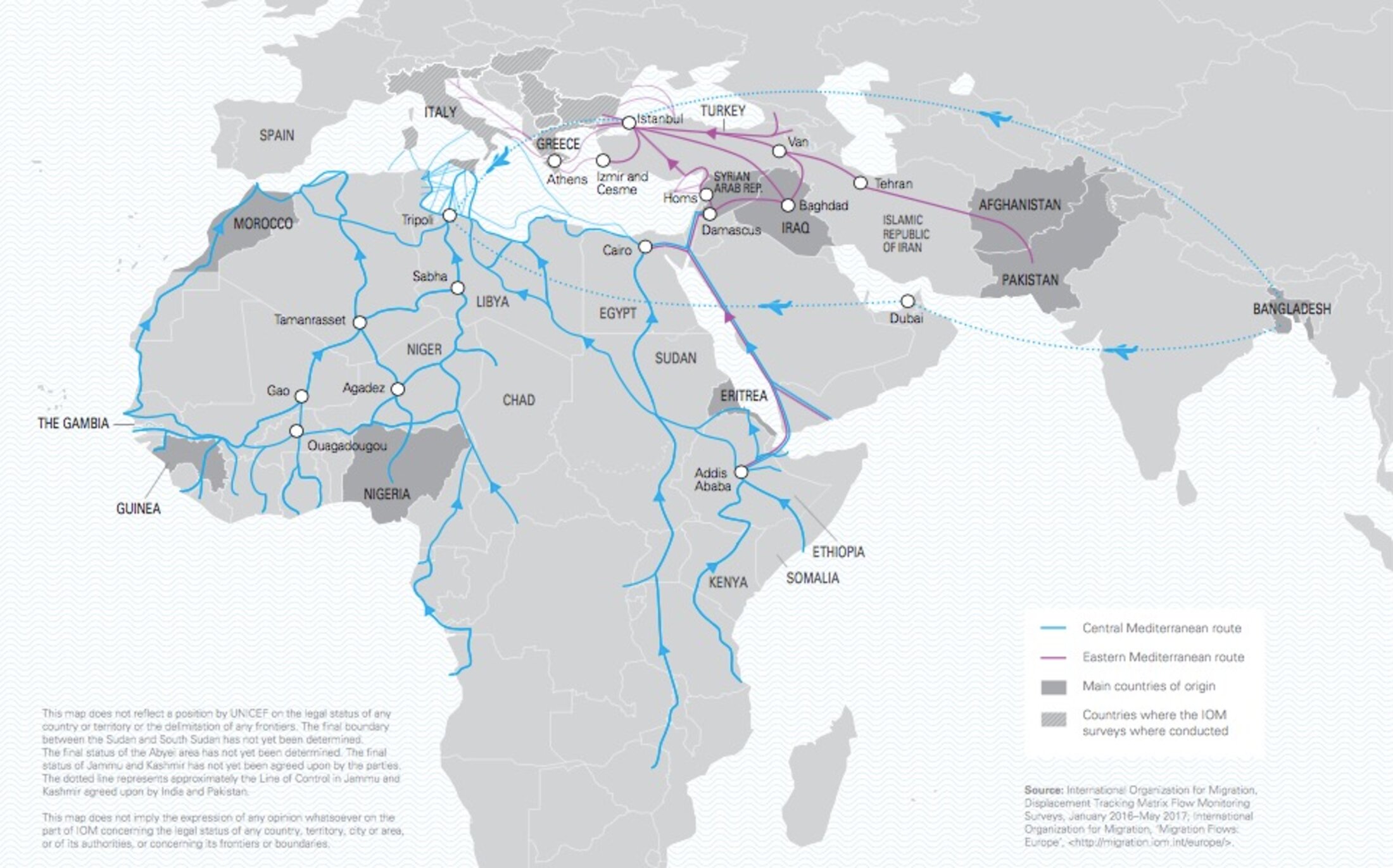

The UNICEF and the IOM study found that adolescents and youths crossing to Europe from the east who complained of exploitation along the way numbered “four to five times” less numerous than those who used the central route through Libya. Those migrants from sub-Saharan countries, the report noted, were clearly more at risk because of racism.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

“On both routes, additional years of education and travelling in a group, whether with family or not, afford young migrants and refugees a measure of protection. But where they come from outweighs either of these factors,” it said. “An adolescent boy from sub-Saharan Africa, who has secondary education and travels in a group along the Central Mediterranean route, faces a 75 percent risk of being exploited. If he came from another region, the risk would drop to 38 percent.”

“Anecdotal reports and qualitative research from the Mediterranean region and elsewhere suggest that racism underlies this difference. Countless testimonies from young migrants and refugees from sub-Saharan Africa make clear that they are treated more harshly and targeted for exploitation because of the colour of their skin.”

The two UN agencies call for a “multi-pronged” strategy that includes the establishment of “safe and regular migration channels” as one measure for reducing the involvement of people traffickers and alternative solutions to placing minors in detention centres. The protection of the rights of children and young migrants, they argue, “entails investing in education and other basic services, coordinating child protection efforts across countries, and fighting racism and xenophobia in the countries migrants and refugees travel through and the ones in which they seek to make their lives”.

-------------------------

- The French version of this report can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse