France's anti-terrorism prosecution unit has opened a preliminary investigation over “crimes against humanity” in relation to former Rwandan military spy chief Aloys Ntiwiragabo for his suspected role in the genocide against the Tutsis in 1994. News of the probe came after Mediapart revealed how we had tracked the former military officer down to his new home in a quiet suburb of Orléans, 75 miles south-west of Paris.

Prosecutors at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) have in the past accused Ntiwiragabo of being one of the architects of the genocide in Rwanda in 1994. The United Nations says this massacre led to 800,000 deaths, most of them from the minority Tutsi people.

According to a judicial source cited by news agency AFP, no formal complaint had been made against 72-year-old Aloys Ntiwiragabo in France, and at the time that Mediapart found him he was not actively being sought by Interpol, nor by the French or Rwandan justice systems. ICTR warrants for his arrest had been dropped some years ago, the source added.

The crimes against humanity unit based at the judicial investigations court chambers in Paris did try to call Aloys Ntiwiragabo as a witness in 2012 as part of an investigation, and asked the Rwandan authorities for help. The Rwandans said that Aloys Ntiwiragabo had taken refuge in an African country.

“It's amazing, just incredible! This man is very important,” was the reaction of Dafroza Gauthier, co-founder of the Collective of Civil Parties for Rwanda, which draws up complaints against Rwandan genocide suspects, when told Ntiwiragabo had been traced. She and her husband Alain are two of the key figures in tracking down potential Rwandan genocide suspects.

“We were told that this guy was somewhere in Africa, that he often moved around. We were also told that he was dead. But in the end it's always the same scenario, it's like the case of Félicien Kabuga,” she said.

Kabuga is a Rwandan businessman seen as the financier of the genocide against the Tutsis and who was arrested on May 16th 2020 in Asnières-sur-Seine, a north-west suburb of Paris, having spent 13 years in France.

The question arises as to how Aloys Ntiwiragabo himself could have come to France and lived here without being detected – until, after seven months of work, Mediapart tracked him down.

In a bid to find him, Mediapart went through all the statements taken by the various Rwandan associations in France and come across references to Aloys Ntiwiragabo's wife, Catherine Nikuze. She had come to France on March 3rd 1998 and was granted political asylum here on September 22nd 1999.

The following year she had set up home with her two children in a dreary suburb of Orléans where, without making waves, she was soon taking part in the activities of the Rwandan extremists in exile. In 2005 Catherine Nikuze became a French citizen and took the surname Tibot.

On the outside of the social housing block in Orléans where Aloys Ntiwiragabo was secretly living in a third-floor apartment, only Catherine Tibot's name appeared on the intercom. Yet on the letter box inside the entrance hall there were three names: Nikuze, Tibot and Ntiwiragabo.

Catching the former soldier out was not that simple however, as the former spy chief and head of a clandestine organisation was discreet and cautious about his presence in the city.

Mediapart visited the Orléans suburb six times between December 2019 and March 2020, changing our appearance and itinerary each time in order to check information without attracting attention.

A ritual emerged: on Sundays the major general went to mass. Going to church is an important act for these Rwandan fighters who call themselves the abacunguzi or 'saviours'.

His hood fixed tight around his face and his hands shoved deep into the pockets of his black jacket, Aloys Ntiwiragabo would walk with a positive step through the aisles at the morning market. Behind his glasses his gaze remained alert. Catherine Nikuze – now Tibot – followed him with a more unsteady gait.

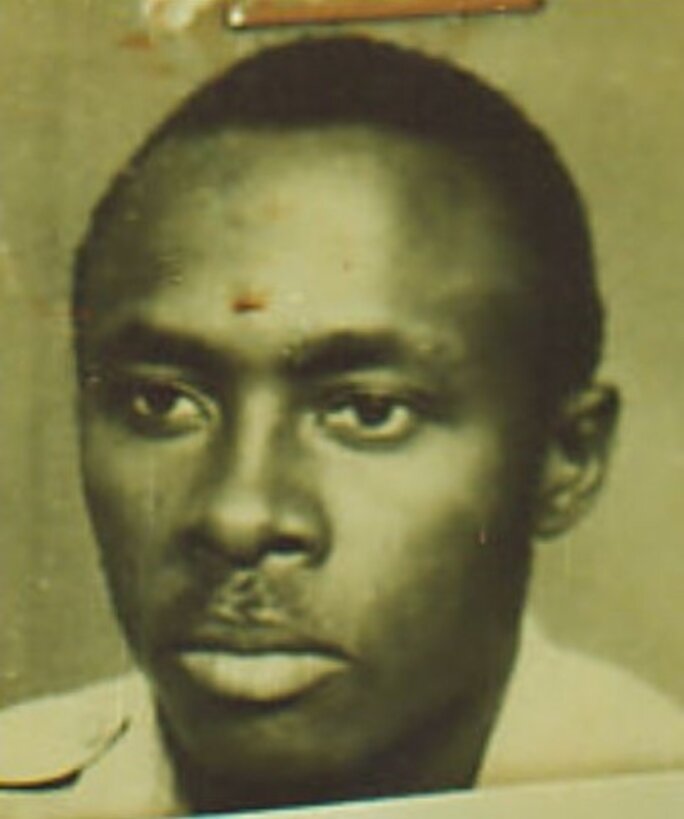

No one paid any attention to the old man with a severe manner and slightly paranoid behaviour. We filmed him discreetly. “His face has changed with age. But I recognise him,” said Richard Mugenzi, who worked for Ntiwiragabo in military intelligence, when Mediapart showed him the photos in the spring.

Another member of the Rwandan intelligence services as well as a former Rwandan civil servant formally identified him too. Contacted by Mediapart, sources close to the Rwandan presidency and current intelligence services were also convinced that it was indeed the former military spy chief.

But how can one be certain after so many years? The man had become a ghost. Officially his only address was at his lawyer's place in the XIVth arrondissement or district of Paris and there was no other trace of him.

Yet it was indeed Aloys Ntiwiragabo who pushed open the door of the post office in the Orléans suburb where he lives on July 10th 2020, and where he picked up a registered letter addressed to his true identity. On the acknowledgement of receipt, which Mediapart has seen, he ticked the box for 'addressee' and signed it.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

This shows that not only does Aloys Ntiwiragabo live at that address, he also had identity documents in his name.

Mediapart first tried to make contact with him in March. A man picked up the phone and refused to confirm or deny Aloys Ntiwiragabo's presence in the home. After that no one picked up the phone. His lawyer did not respond to requests for a comment.

So had Aloys Ntiwiragabo relaxed his guard a bit? It is true that he has not been on the list of wanted fugitives for years. He was one of the group of men for whom the indictment had not been drawn up by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) in the allotted time. The searches for suspects had proved too long and too demanding, and the trials had become interminable. So in the middle of the 2000s the prosecutor at the ICTR, based at Arusha in Tanzania, decided to call a halt, with the exception of a few cases.

Perhaps this meant those men who were no longer being actively searched suddenly felt safe. France has taken no steps to bring the fugitive to justice for more than a decade, even though it has had the chance on several occasions.

Aloys Ntiwiragabo's task in vanishing was made easier by the fact that he has featured very little in the French press over the years. He comes from a village in the north of the Rwanda and moved in the circles of the most hard-line extremists. He commanded the gendarmes in the capital city Kigali until 1993 and for a long time Captain Pascal Simbikangwa, who in 2014 was sentenced to 25 years imprisonment in France for complicity in genocide, worked under his orders. He also belonged to an inner circle in Rwanda known as the 'Akazu'. This group adopted the ideology of Hutu Power, an ethnosupremacist ideology which led to the genocide by sections of the majority Hutu people against the Tutsis.

In June 1993 Aloys Ntiwiragabo became head of Rwandan military intelligence, known as G2, and was appointed as deputy chief of staff for the Rwandan army. “He was a fanatic,” said Richard Mugenzi, who worked at G2.

Mugenzi recalled the mood inside the intelligence service. “Everything was planned, there was a vision. That involved getting rid of the Tutsis. A final solution,” he said.

G2 drew up a list of “enemies” defined as “the Tutsis in the interior and the exterior”, and also political opponents or even people who were just considered to be too moderate. The prosecutor at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda attributed authorship of these lists to Colonel Ntiwiragabo, as his rank was in the Rwandan army.

In drawing up these lists Aloys Ntiwiragabo was thus at the heart of the planning for the genocide. “[He] was responsible for the official and unofficial aspects of this plan,” stated Mugenzi.

During the genocide itself the G2 spread false information on the Rwandan army radio network and falsified adverse messages it intercepted in order to attribute its own crimes to the enemy.

“During the course of the genocide the military escalated the number of their messages, some of which clearly called for the extermination of the 'lnyenzi' (“cockroaches”) and the 'lbyitso' [editor's note, supporters of the Tutsi-led Rwandan Patriotic Front],” recalls radio presenter Valérie Bemekiri, speaking to a French investigator many years later. She worked for the Radio Télévision Libre des Mille Collines (RTLM) radio station which is said to have played a “crucial role in creating the atmosphere of charged racial hostility that allowed the genocide to occur”. At the time she cited Aloys Ntiwiragabo as being one of three “main players” who “came to see the CEO to give him the reports to pass on”.

Indeed, RTLM broadcast the lists of people to execute that had previously been drawn up. These lists were given to the presenters by the station's CEO - Félicien Kabuga – and contained the addresses, places of work and the places visited by the people targeted.

During the genocide Aloys Ntiwiragabo took part in the daily meetings of the general staff of the Rwandan armed forces. He is one of only two participants in those meetings to have never been arrested or tried.

According to the non-governmental human rights organisation African Rights, Aloys Ntiwiragabo ordered the assassination of officers who did not cooperate with those carrying out the genocide. He is also said to have made a police station in Kigali available for militias to torture, rape and execute Tutsis.

In the indictment it drew up for the first trial of soldiers involved in the massacres, the prosecutor of the ICTR cited Aloys Ntiwiragabo among eleven individuals who “from late 1990 until July 1994 … conspired among themselves and with others to work out a plan with the intent to exterminate the civilian Tutsi population and eliminate members of the opposition, so that they could remain in power … they organised, ordered and participated in the massacres perpetrated against the Tutsi population and of moderate Hutu”.

Ntiwiragabo's predecessor as head of the G2 was jailed for life. Out of those eleven men named in the indictment, the ICTR convicted five and acquitted three but never managed to capture the final three people named, one of whom was Aloys Ntiwiragabo.

On the run and then arrival in France

In July 1994 many of those behind the genocide in Rwanda fled to Zaire – now the Democratic Republic of the Congo or RDC – convinced they would soon return to Rwanda itself. Aloys Ntiwiragabo was among those who left. By 1996 he was in Kenya.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

It was on July 18th 1997 that investigators at the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda launched operation 'Naki' to arrest the fugitives. Aloys Ntiwiragabo was one of their targets. When the Second Congo War broke out in 1998 the Rwandan fugitives allied themselves with the new Congolese government and joined the conflict. Aloys Ntiwiragabo became their “supreme commander”. The different factions that he controlled came together to form the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR) of which he became major general; he had been a colonel in the Rwandan army. He set up what the United Nations has since called “negative forces”.

As the journalist Jean-François Dupaquier has shown, it was these Rwandans previously involved in the genocide who imported into the Congo the use of mass rape as a weapon of war. The FDLR put women in slavery, recruited hundreds of child soldiers, subjugated local peoples and committed innumerable atrocities which have been documented by the UN and by human rights NGOs.

Within a few years, however, the presence of the FDLR had become one of the main obstacles to the peace process in the region. For the sake of appearance the organisation decided to replace those leaders who were too closely linked to the 1994 genocide with individuals who were less intimately associated with it.

So Aloys Ntiwiragabo withdrew and left his headquarters at Kinshasa in the RDC and went off to a retirement which had been prepared in advance. For since his departure from Rwanda he had also been involved in another conflict, this one in the Sudan, where he had first visited in 1997.

At that time the government in Khartoum, which was involved in a violent conflict with secular socialist forces from southern Sudan, welcomed foreign combatants with open arms. Those involved in the genocide in Rwanda, plus Ugandan rebel forces, thus joined the other militia fighting for Omar al-Bashir's regime in the Sudan.

When he returned to the Sudan after four years in the Congo Aloys Ntiwiragabo was no longer an official member of the FDLR hierarchy and claimed he no longer had links with the organisation that he had founded and led. Even so, he was suspected of keeping close links with it.

By this point the former head of Rwandan military intelligence wanted to leave Africa. He had a solid support network in France, though he was unable to seek asylum there. Yet though he was still at this point being actively sought by the ICTR, in 2001 Ntiwiragabo twice dared to go in person into French diplomatic missions to ask for a long-stay visa. First of all he went to the French consulate in Khartoum, then to the consulate at Niamey in Niger. His criminal past could have justified not just outright refusal of the visa but also immediate arrest by the French or Niger authorities. Nothing happened, however.

France's foreign affairs minister at the time was Hubert Védrine, who had been deputy chief of staff at the Élysée at the time of the Rwandan massacre. Contacted by Mediapart he said: “Let me stop you there. I know Mediapart's position on Rwanda and so I'm not responding to any precise question and I won't enter into detail. The French media are biased and they would never be brave enough to say that they have written false stuff for 20 years.”

Could the minister at the time have been unaware of Aloys Ntiwiragabo's applications for a visa? Mediapart has seen confidential documents, in particular those from embassies, which show that it was then customary for consulates and prefectures to raise information about Rwandan figures higher up the chain of authority.

The genocide suspect's application for a visa took ten long years to be processed. In 2011 the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the Interior Ministry finally turned it down. Could this have provided a fresh opportunity to arrest the Rwandan? At the time the minister of foreign affairs was Alain Juppé, who had held the same post during the genocide. He did not respond to Mediapart's request for a comment.

Aloys Ntiwiragabo and his wife tried to get the visa refusal overturned. But their attempt was turned down by an administrative court in Nantes in west France in 2014 and their subsequent appeal was rejected the following year.

But had Aloys Ntiwiragabo already arrived in France by this time?

Two months after Aloys Ntiwiragabo first made his visa application in 2001 the French judge Jean-Louis Bruguière met the latter in Kinshasa. This was to question him over the deadly attack on the plane carrying Rwanadan dictator Juvénal Habyarimana on April 6th 1994, the act which triggered the genocide.

By this time Jean-Louis Bruguière had spent three investigating the new regime in Rwanda. It is now established that the judge's somewhat dubious scenario concerning the involvement of the new Rwandan authorities had been influenced by Rwandans who had been implicated in the genocide and by members of the FDLR. This scenario was further fuelled by Aloys Ntiwiragabo himself when he was questioned by the French judge.

Is it possible that his contribution to a French's judge's efforts to incriminate the Rwandan authorities over Habyarimana's killing led Aloys Ntiwiragabo to believe that he would be welcome in France? Was this feeling strengthened when in 2006 Judge Bruguière launched nine arrest warrants relating to senior figures in the new Rwandan regime?

This view may have been strengthened further when at the same time the ICTR, which was supposed to complete its works within a reasonable time frame, decided against issuing any more indictments against some people suspected of involvement in the genocide, among them Aloys Ntiwiragabo.

Mediapart has not been able to establish the date at which the Rwandan came to live in France. But did France knowingly let him in the country?

The authorities certainly knew about the presence of Ntiwiragabo's wife Catherine Nikuze in France. The police counter-intelligence agency the Direction de la Surveillance du Territoire (DST) carried out two “background checks” in Orléans after 2000. Mediapart has seen two documents from the DST, which were declassified for use in judicial proceedings but in which the contents have been almost entirely redacted.

On May 3rd 2001 the counter-intelligence agency produced its first nine-page intelligence report on Catherine Nikuze, which was marked “classified”. On September 19th 2001 a second report, this one eight pages long, was written about the former Rwandan diplomat Jean-Marie Vianney Ndagijimana, who was a member of the local Association des Rwandais de l’Agglomération Orléanaise (ARAO) of which Catherine Nikuze had been treasurer since 2001.

Given that his wife was being watched, and that he had been planning to come to France since 2001, how could Aloys Ntiwiragabo have come into France unnoticed, especially as the former spy chief has never really vanished entirely from the landscape. In 2018 he even published a book in which he gave his side of the story. The word 'genocide' is noticeably absent from its pages.

Then in February 2019 Mediapart revealed the contents of a report from France's external intelligence agency the DGSE which named Hutu Power extremists as having ordered the attack on Habyarimana's plane on April 6th 1994. Aloys Ntiwiragabo reacted with a “clarification” on an extremist site hosted in France.

Mediapart asked France's anti-terrorism prosecution unit whether it had investigated Aloys Ntiwiragabo but it declined to comment.

“You get the impression that France agreed to shelter these big shots without anyone noticing. There must be some accomplices involved behind all this to enable them to live like that, said Dafroza Gauthier, co-founder of the Collective of Civil Parties for Rwanda. “What are the relevant authorities going to do when they discover this? We hope they're going to do their job and arrest him so that he is answerable to the law.”

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

English version by Michael Streeter