Claude Sinké, 84, is being held in custody by police for “attempted murder” after an attack on a mosque at Bayonne in south-west France on Monday October 28th 2019 which saw two worshippers shot and wounded.

According to the prosecution authorities Sinké was “completely unknown to the police and to the legal system”. Detectives found a stash of weapons at his home, four grenades, a 9mm pistol, several cartridges and a rifle, but they were all legally declared.

During questioning the 84-year-old admitted having set fire to the mosque's door and also a nearby vehicle which was completely destroyed. But he denied having “wanted to kill anyone”, said the local prosecutor Marc Mariée. The pensioner said he had carried out “recces” to ensure his attack would be at a time when few people would be at the mosque.

However, so far the investigation, and in particular video surveillance cameras, has contradicted his account. Claude Sinké arrived with a petrol can at the mosque intending to set it alight, and then aimed several shots at two worshippers aged 78 and 74 outside the building, wounding both of them. One of these two men tried to get away in his car. But Claude Sinké is said to have doused this car in petrol and then set it alight, even though the injured man was still inside. Both victims were seriously injured but are now in a stable condition in hospital.

According to the prosecutor Sinké, who stood as a candidate for the far-right Front National (FN) – now Rassemblement National (RN) – in local elections in 2015, explained his actions as a “desire to avenge the destruction of the Paris cathedral [editor's note, Notre-Dame], maintaining that the fire at this building was caused by members of the Muslim community”. The theory that the fire in April was a criminal or terrorist attack has been excluded by investigators. But at the time this theory was raised by several politicians – including hardline nationalist Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, who continued in his doubts over the cause, and an RN official Jean Messiha – and by far-right websites.

On Wednesday October 30th, two days after the attack, prosecutors said that Sinké suffered from a “partial deterioration” in his critical facilities. A formal investigation has been opened into attempted murder, aggravated criminal damage, and violence using a weapon, and the suspect will remain in custody. However, prosecutors said the case would not be handed to the anti-terrorist unit.

Since the attack on Monday Rassemblement National (RN) has hastily sought to distance itself from its former candidate in the 2015 elections for France's départements or counties. On Twitter the party's president Marine Le Pen condemned an “unspeakable act completely contrary to all our movement's values”. Nicolas Bay, a Member of the European Parliament and vice-president of the RN group at the European Parliament, told CNews television: “He's an extremist who had no place in our ranks.”

But the party got itself in a muddle when trying to explain why their former candidate had left the FN, as it then was. Nicolas Bay said Sinké had left the FN himself “because, it seems, he had ideas which had nothing to do with ours”. But the man who headed the 2019 European election campaign for the party, Jordan Bardella, said that Sinké had in fact been removed from the party in 2015 “by local officials”.

The RN's official spokesperson, Sébastien Chenu, said that “after an illness” Claude Sinké had made “incoherent....almost crazy remarks”and that he had moved away from a “political” approach. Julien Odoul, an elected representative for the RN, thought that the attack was “in all likelihood the work of someone unbalanced” and asked that people did not conflate the attack on the mosque with the party. In an official statement the RN said that it was its “departmental federation” which had “removed” Sinké after the 2015 elections for having made comments “judged contrary to the political spirit and line of Rassemblement National”.

However, when Claude Sinké was officially made a candidate for the Front National for the département elections in March 2015, he had already publicly made hateful comments. On October 22nd 2014, on a Facebook fan page of the controversial commentator Éric Zemmour, he wrote about “a war against the Islamists” and added: “They will perhaps be flushed out the day they put a bomb in a school or a cinema”. A month earlier he had complained on his own Facebook account of being “treated like a racist”.

These comments, which can be found via a simple search of his name on Facebook, did not seem to have bothered the Front National at the time. Indeed, before the 2015 elections the party congratulated itself for having put in place a team to check up on the social media profiles and comments of its candidates. Nicolas Bay, who was at the time the party's general secretary, said of this new measure in November 2014: “If some photos or images are completely contrary to our values, the candidates will be excluded.”

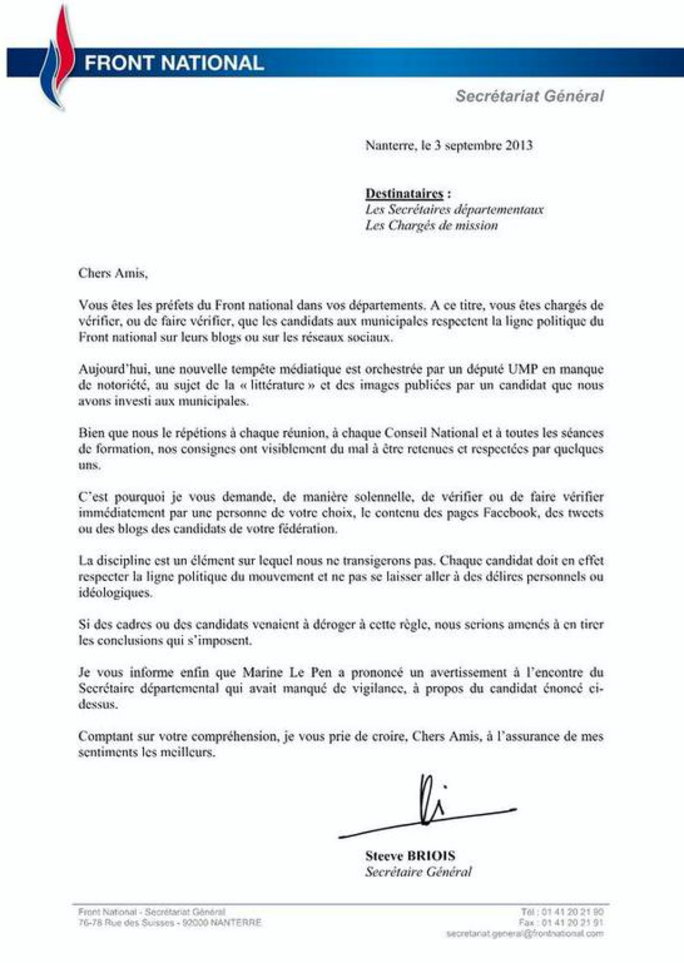

In fact, in September 2013 the FN leadership had sent an internal note to département secretaries asking them to “check, or get it checked, that the candidates in the municipal [elections] respect the Front National's political line in their blogs and on social networks” (see document below). This was followed a month later by a new letter in which the party asked local officials for a “town by town report on the good performance” of each candidate's Facebook account.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

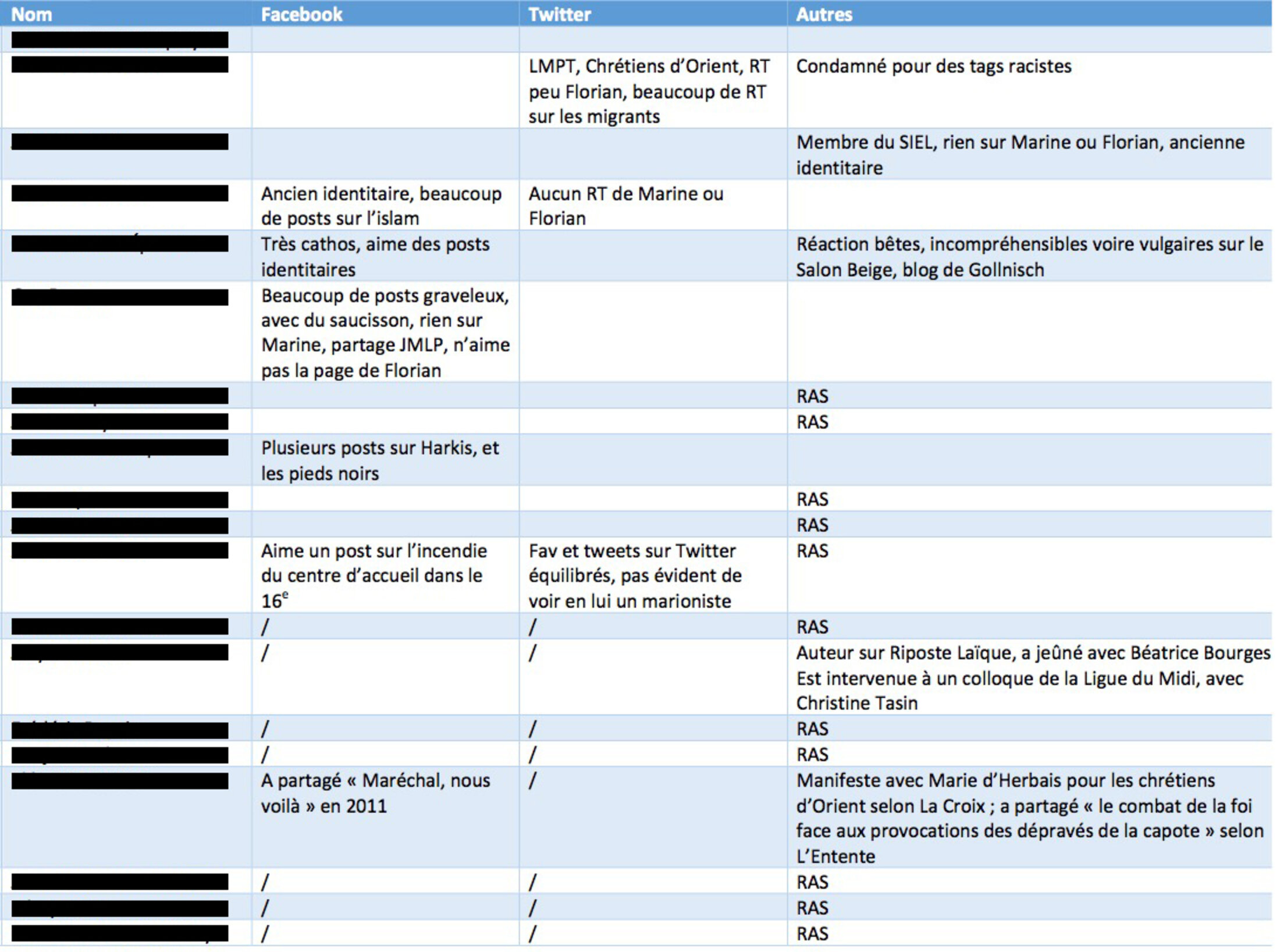

This supervision of social media continued. As Mediapart has pointed out, in 2017 the Front National drew up unofficial files on its candidates ahead of them being formally adopted for the Parliamentary elections later that year. The opinions, social media comments and past politics were all scrutinised. Here are the types of comment found in these secret files on the various candidates: “Seems ok but keep an eye out anyway; she seems obsessed by foreigners and Muslims”; “Islamophobic excesses, convicted for incitement of racial hatred”; “Convicted for racist graffiti about migrants”; “Former skinhead, convicted in in 2012 for violence”. Nonetheless, 25 candidates who were the subject of alerts in these files were still adopted as candidates by the party.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

Marine Le Pen regularly claims in the media that members of the party who make unacceptable remarks will be punished “with a speed and toughness that I haven't seen much in other political parties faced with mavericks or abuses”, she said in October 2013 on the 'Mots Croisés' programme on France 2 television station.

As recently as last week, and following revelations (see here and here) about the racist and violent past of a 34-year-old RN candidate in Strasbourg, north-east France, for the 2020 local elections, Le Pen insisted that she had not been aware of his background and announced his suspension.

It is the same story over and over again. A RN candidate is caught being racist or xenophobic or inciting hatred, it becomes a story in the media, the party speaks of “excesses”, suspends the person concerned and then congratulates itself in the media for how it cleaned up the mess.

In fact, as Mediapart has highlighted, Rassemblement National has set itself an impossible cleaning up task. One only has to delve into the Facebook and Twitter accounts of RN candidates, as many in the media have done in recent years (see examples here, here and here), to see the everyday racism which still exists in the party ranks.

Usually the RN only imposes sanctions when the offending comments are made public by the media. As sociologist and Front National specialist Sylvain Crépon told Mediapart in 2013, for the party it is simply a matter of a tidying up process: “For the FN, cleaning things up doesn't mean flushing out the candidates who say these remarks and excluding them, but to make sure they clean up their Facebook page. There are no checks on the ideas, but checks on the broadcasting of those ideas.”

The researcher also said that the party's training programme for candidates was not about “transforming those ideas”. He said: “They are not told 'no, you can't say that, that's scandalous', but rather 'you can't say it like that'. It's explained to them that they have to change a 'negative' sentiment into a 'positive' one by saying 'there's unfair competition, wages are going down, it is about the national priority, immigrants should return to their country, including for their sake as they don't have roots here.'”

Over the years the Front National has used different lines of argument: in the 1980s the debate was about the economic impact, it was cultural in the 1990s and today it is about the Republic's values and secularism. But, behind this, says Sylvain Crépon, the “idea remains the same” which is about “preserving purity of identity”.

Head of domestic intelligence agency raised alarm in May 2016

In the face of Marine Le Pen's strategy of de-demonizing the party's image and of excluding a section of the most obviously controversial individuals, some Front National sympathisers preferred to head off towards small ultra-right groups with more radical views or towards the rapidly expanding online world of the far right. For the far right is not just making progress in the ballot box, but on the internet too (see Mediapart's article here).

On certain sites in what is called in French the 'fachosphère' – as in 'fascist' – some radical members talk about carrying out attacks against the Muslim community. One such is the Réseau Libre or 'Free Network' site, which Mediapart investigated in April 2019. This site, which has changed its name many times over the years, features conversations between its 800 or so strong community of white supremacists who are obsessed by the fear of anyone different, and who are simply waiting for a spark to take action and carry out their own Islamophobic attacks.

For example, the day after the second anniversary of the November 13th 2015 terrorist attacks in Paris, a site member called 'Merlin' – one of the mainstays of the community – pledged to “kill anyone who might be Muslim, men, women, children. And without pity or remorse.”

In the summer of 2018, meanwhile, 'Glock 17' issued a call to arms: “Clean your cannons, oil your gun breeches, and fire into the crowd!” At the end of September 2018 'Anonyme' said: “Can't wait for the first patriotic salvo! My trigger is itching, my index finger is starting to get cramp...” And then, as the third anniversary of the November 13th attacks approached, site member 'Povbête' said: “If I were smart I'd certainly go and blow up a small mosque, to cheer myself up and to make those filthy 'muzz' [editor's note, an abbreviation for Muslims] understand that we don't want them.”

The ideas spread on this site were the same as those that inspired the Australian terrorist in the mosque shootings in Christchurch, New Zealand, in March 2019. These ideas are the theory of the “Great Replacement” espoused by the far-right essayist Renaud Camus; the perceived failure of a Front National judged to be too moderate; and Islamophobic attacks advocated to defend the white race.

In terms of the profile of the site's members, there were mostly older men, often nostalgic for the days of the OAS – the Organisation Armée Secrète which fought against Algerian independence – and in some cases they are former police officers or gendarmes. Some are members of the Rémora networks, which were founded by an ex-officer in the former police intelligence service the Renseignements Généraux and which calls on civil society to rise up and take on the role of soldiers, police and gendarmes in case of an attack by “Islamo-terrorists”.

Criminologist Xavier Raufer, who was quoted on Réseau Libre, and who said he had not previously known about it, played down the dangers posed by people with such profiles. Talking to Mediapart, he dismissed it as a “movement of conspirators from the Midi [editor's note, southern France] in France who play at it by preparing stuff which will never take place”. It was, he went on, made up of “former French Algerian conspirators” who “having drunk three litres of Cahors [wine]” then go and “put a pig's head in front of a mosque”. He described them as harmless “storytellers, nutters, alcoholics”.

Enlargement : Illustration 4

In recent months, however, there have been tragic examples of where some far-right sympathisers have indeed shown their willingness to commit acts of atrocity. The attacks in Christchurch in March are one case and another recent one was the targeting of a synagogue and a Turkish restaurant in Halle in Germany on October 9th.

Those are not isolated examples. In June 2019 a German prefect, who had received several death threats from far-right groups for having supported Chancellor Angela Merkel's policy of welcoming migrants to Germany, was murdered by a neo-Nazi who had already been convicted several times. In November 2018 a corporal in the British Army was jailed for eight years for being a member of a banned far-right group, National Action, for whom he was recruiting. According to reports of his trial, the corporal “believed in a coming 'race war' and wanted to help establish an all-white stronghold in a Welsh village”.

In the same year an Italian man was jailed after shooting at and wounding six African people in the middle of Macerata in central Italy. At his home detectives found a copy of Hitler's Mein Kampf and a history book about Benito Mussolini. In 2017 a German military officer was arrested over suspicions that he was planning a terrorist attack, having earlier sought to pass himself off as a Syrian refugee. In Britain the British MP Jo Cox was murdered in 2016 by an unemployed gardener who nursed a hatred of “traitors” to white people.

Meanwhile in France an ultra-right group called AFO (Action des Forces Opérationnelles) was disbanded in June 2018 (see article here). The group was training itself in the use of home-made explosives and planning attacks against Muslims. Some members of the group were considering plans to poison halal food.

Then in June 2019 two people were injured in an attack on a mosque in Brest in western France whose imam, Rachid Abou Houdeyfa, had been criticised in the past for his reactionary stances but was also targeted by Islamic State after adopting more mainstream Islamic views. Little has emerged about the suspect in the case, a 21-year-old man. In a bizarre letter the man, who called himself Karl Foyer, described himself as “Norman by origin” and said that “three hooded men” had ordered him to “cut the throat of the imam in Brest” and to “push a French flag up his anus”.

Governments across the European Union are aware of the problem. On October 8th 2019 the EU's interior ministers met and among other things discussed “right-wing violent extremism and terrorism”. They agreed that while such terrorism was today not the “main risk” it was however growing. One aim of the discussion was to create political momentum to “strengthen the prevention, detection and addressing of violent extremism and terrorism”.

The threat of right-wing extremism is confirmed by the worrying conclusions of a recent confidential report from Europol. This showed that far-right groups are buying weapons and making explosives. As Mediapart revealed, the French intelligence services estimate that some 350 members of the far right in France legally own one or more firearms.

The Europol report also states that the European ultra-right is apparently recruiting from among the ranks of the military and the police. This corroborates what Mediapart has been reporting since the spring of 2018 about France (see report here). France's domestic intelligence agency, the Direction Générale de la Sécurité Intérieure (DGSI), had in fact alerted the authorities about the growing proportion of soldiers or members of the forces of law and order who have joined far-right groups.

The intelligence services then had “around 50 police officers, gendarmes and soldiers” among their “targets”, who were monitored for their links with the “violent far right”. That is close to double the number of targets watched because of their adherence to radical Islam, according to the declarations of the interior minister Christophe Castaner. After the recent killings at police headquarters in Paris, in which three officers and a police civilian were stabbed to death, the interior minister has talked of around 20 police officers and about ten gendarmes who are being monitored because of suspicions they have converted to Muslim fundamentalism.

In May 2016 the then-head of the DGSI, Patrick Calvar, raised the alarm on the issue when addressing the defence and armed forces committee at the National Assembly. Calvar spoke of the need to “anticipate and block” groups from the “ultra right who are just waiting for confrontation” and who might want to “trigger intercommunity clashes”.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter