Xavier (last name withheld) runs an oyster farm in this part of south-west France where the river Gironde, running west from Bordeaux, spills out into the Atlantic Ocean. Oyster rearing is a centuries-old activity in and around Nieulle-sur-Seudre, where Mediapart bumped into him last weekend.

He said his friends now talk of nothing else but the terrorist shooting massacres and suicide bombings in Paris on November 13th which claimed the lives of 130 people and left more than 350 wounded, and for which responsibility was claimed the Islamic State group. “I hear talk of ‘It’s the Arabs again!’” Xavier recounted. “I say ‘hold on, they’re not all like that’. What’s more it’s the truth. It suffices that there’s zero point zero, zero, zero-one percent of the rotten for everyone to be tarred with the same brush. And even then, you could add another zero.” But, Xavier warned, “With all this rubbish everybody becomes racist.”

On the car park in front of the baker’s shop, he waves to folk he knows, dropping a flirtatious “you look as lovely as a flower” to some of the women. While Xavier said he himself will go and vote in the first round of regional elections next Sunday, the interest in the election is waning. “With all that [editor’s note: coverage of the Paris attacks] it’s been eclipsed,” he said. “Even on TV nobody talks about them. There’s no publicity, as it were. People don’t really care much.”

Back in 1990, Nieulle-sur-Seudre was a typical oyster-farming village with a population of about 500, set in picture-postcard surrounds of emerald-green fields and former salt marshes where cows grazed. Over the past 25 years, the population has more than doubled, and estates of new houses have sprouted around the village. Now the unemployment rate in the surrounding area is the worst of any in the newly created Aquitaine-Poitou-Charentes-Limousin region of centre-west France. Those in Nieulle-sur-Seudre who do have jobs are mostly blue-collar workers and public sector employees whose workplaces are in the neighbouring towns of Marennes, Rochefort and Royan.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

While there are a few shops in the village centre, everyone needs a car for the major shopping tasks, for commuting to work, and for taking the children to sports grounds and other leisure activities. In the départementales (county) elections held earlier this year, 30% of the registered electorate in Nieulle-sur-Seudre voted for the far-right Front National (FN) party – the highest score obtained by the FN in the local area in and around the nearby town of Marennes.

Marennes, with a population of just more than 5,500, is situated about 12 kilometres north-west of Nieulle-sur-Seudre, closer to the Atlantic coast and the Oléron island that sits immediately in front, from where derives the celebrated oyster appellation of Marennes-Oléron. Ten days before the terrorist attacks in Paris, Mediapart had travelled to Marennes to report on the regional election build-up.

Set in a département dominated by the mainstream Right, and where the FN has made consistently increasing gains at every recent election, Marennes is an oasis for the Socialist Party. Its mayor, Mickaël Vallet, 36, was elected in 2008, the first socialist mayor in Marennes since the 1930s, and who has been re-elected again since.

During Mediapart’s first visit, Vallet took us on a guided tour of the small town, during which he explained that he and his municipal council were leading a campaign against the growing sprawl of house building led by property developers with no regard for a durable model of urbanisation. Similarly, he had placed a ban on the construction of new shopping areas in an attempt to revitalise the town centre.

Vallet is also the campaign director for the socialist candidate in this weekend's regional elections, Alain Rousset, the head of the socialist list of councillors who hope to command the regional council, and during our first visit he appeared certain that the Left would win.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

Mediapart returned to Marennes on November 28th, the day after the official national ceremony held in Paris in tribute to the victims of the Paris attacks when the population was invited by President Hollande to display the French national flag on balconies and windows. The window of the local haberdashery store was decorated with the blue, white and red of the flag, while elaborate tricolor ribbons dangled from the awning of the florist’s. The town hall was covered in miniature flags, and Vallet said he had decided to offer one to every inhabitant “for the next patriotic commemorations”.

Down at the local library, while young children were rummaging through books, a group of elderly adults were sipping champagne. The latter, joined by Vallet, were holding a prize-giving ceremony in a literary competition for best first novel organised by the local Lions Club and which was won by a young Parisian author, Denis Michelis. The ‘Hortense Dufour Prize’is named after a French writer who hails from Marennes, and whose speech at the ceremony that Saturday ended with the call: “Continue with our lives, our books, our projects, without fear or hate.” Dufour’s daughter had known some of the victims of the Paris attacks.

The president of the Lions Club, Daniel de Miniac, is the right-wing conservative mayor of a nearby local village of about 800 inhabitants. He spoke of the “electroshock” the November attacks had caused. “This time, it was even more profound than [the attacks against the magazine] Charlie [Hebdo],” he said. “People are dumbfounded. For the past 15 days they talk of nothing else. I am worried that the extremists will benefit from this fear. You hear more and more talk of exclusion towards the Muslim population. Some no longer hide themselves.”

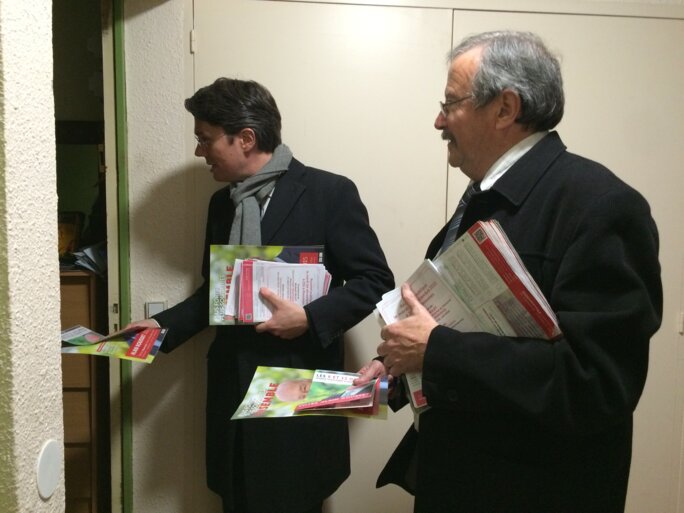

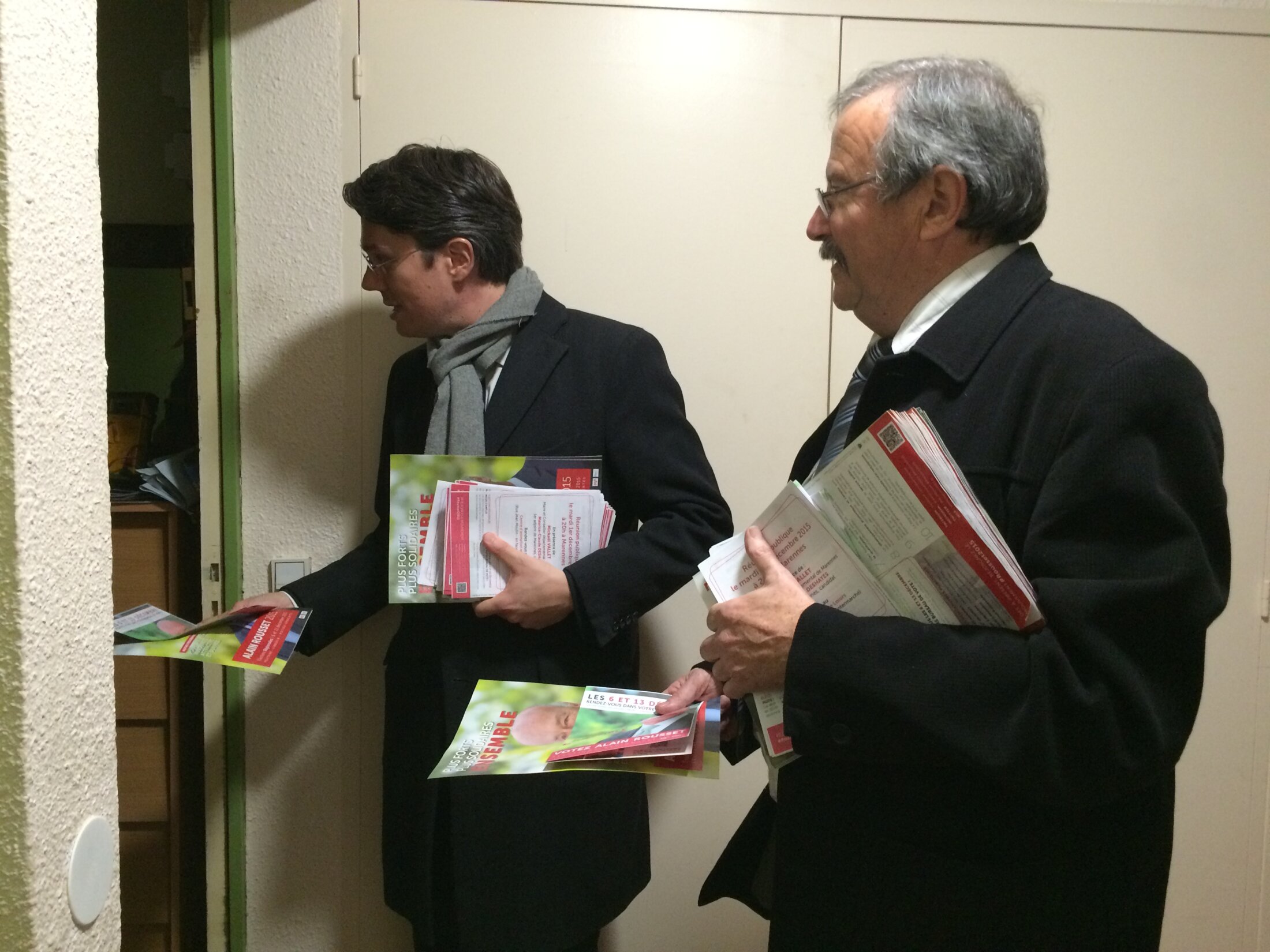

Once the ceremony had ended and people had parted with handshakes and embraces, Vallet returned to his duties as a socialist militant, embarking on some door-to-door campaigning for the regional elections in a subsidized housing block in the town.

The confidence he had, before the Paris attacks, in a socialist victory in the region had now disappeared. On his smartphone he had the results of one opinion poll yet to be published and which showed the lead socialist candidate, Alain Rousset, to have lost ten percentage points of support in just one month. The same poll showed that Rousset’s mainstream Right opponent, Virginie Calmels, (deputy to Bordeaux mayor Alain Juppé and who entered fulltime politics just 18 months ago), had gained two percentage points. Support for the far-right FN party had also increased by two points. “We’re losing ground,” lamented Vallet. “From now on we’re in the margin of error. It would be crazy if Calmels wins.”

Following the Paris attacks, some in the local Socialist Party believed it would benefit from the strong law-and-order measures adopted by the socialist government. But in fact support for the socialists has fallen, and in this newly-enlarged super administrative region, made up of several former regions where a total of three regional councils were controlled by the socialists, victory is now far from assured. Harassed by feverish calls from Rousset’s HQ, Vallet began his door-to-door visits last Saturday saying the end of the campaign could not come quick enough.

In the corridors of the building block, doors opened to reveal, variously, smiling and reticent inhabitants, TVs flashing in the background and sometimes the sweet smell of baking. Joined by his first deputy on the Marennes municipal council, who is also a candidate to become a regional councillor on Rousset’s list, Vallet regularly trotted out his introduction: “Good day to you, it’s your mayor calling”, quickly followed by the question “Are you aware that there are regional elections next Saturday?” (and for some of those he meets, the answer is that they were not). Then it was for Vallet to introduce his deputy, Maurice-Claude Deshaye. “We absolutely must send a Marennais to Bordeaux!” Vallet repeatedly exclaimed, referring to the site of the new regional council.

People were mostly polite to Vallet but few were enthusiastic to take the conversation further. In all his visits, Vallet never mentioned the Socialist Party, and no-one engaged conversation with him about President François Hollande, or the socialist government. “This election is very presidential,” Vallet told Mediapart. “There is an enormous national weight to it.”

In one of the stairwells of the building, Vallet presented a woman who was his cousin. “I don’t hear any talk about the regional elections,” she said. “On the other hand, there is a lot of talk about security, the misfortune of people. People are switched on to [rolling TV news channel] BFM-TV all day long. We came together for the [national] minute of silence [held in tribute to the Paris attack victims]. We’ve got that in our heads the whole time.”

One of the doors Vallet came to was opened by Anne Saussieau, a retired woman with impeccably styled hair. A socialist supporter, she promised she would turn up for the vote next weekend. She said she currently often switches off her TV, tired by what she called the “brainwashing” in coverage of the November attacks in Paris. “There are people who that could negatively influence,” she said. The socialists must hope for a big turnout next Sunday to retain hope of winning control of the region in the second and final round on December 13th.

-------------------------

The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Graham Tearse