“Hair is a trace, a marker, a symbol. Of our caveman past, of our brutishness, our virility. Of the differences between the sexes. It reminds us that virility goes hand in hand with violence, that man is a sexual predator, a conqueror.” These words are those of the well-known journalist and essayist Éric Zemmour, who works for Le Figaro newspaper and CNews news channel, and who has several times been convicted by French courts for inciting hatred towards Muslims.

Aged 62, he is today facing accusations over his behaviour towards women. In the course of recent months Mediapart has gathered several stories concerning enforced kisses and gestures and comments of a sexual nature on his part. When contacted by Mediapart Éric Zemmour declined a request for an interview and made it clear he would not respond to questions put to him on the issue (see the Boîte noire box below).

The controversial journalist once again became the centre of attention after the publication of a post on Facebook by an opposition city councillor from Aix-en-Provence in the south of France on Saturday April 24th. Gaëlle Lenfant, a former official in the Socialist Party (PS) where she was in charge of women's rights, described a scene from a summer conference held by the party at La Rochelle in, she recalled, 2004. She said it took place the day after several senior PS officials including Gaëlle Lenfant had dined with Éric Zemmour. That following day the Le Figaro journalist turned up to take part in a themed workshop that was already underway at the town's Encan conference venue.

Zemmour “recognised me, said hello and asked me what he'd missed,” wrote Gaëlle Lenfant. “I gave him a summary of what had gone on. The workshop ended, I got up and he got up too. Grabbed me by the neck. Told me 'you know, that dress really suits you?' And kissed me. Forcibly. I was so stunned that I wasn't able to do anything else other than push him off and run away. Trembling. Crying. Asking myself what I might have done,” she recalled.

“I had done nothing, said nothing, showed nothing, wanted nothing. It was of course nothing to do with me. I was just a thing that he who defined himself as a 'violent sexual predator' had wanted, and in his world when you want something you help yourself. He helped himself,” Gaëlle Lenfant continued. She then added: “It was years ago but the disgust doesn't go away.”

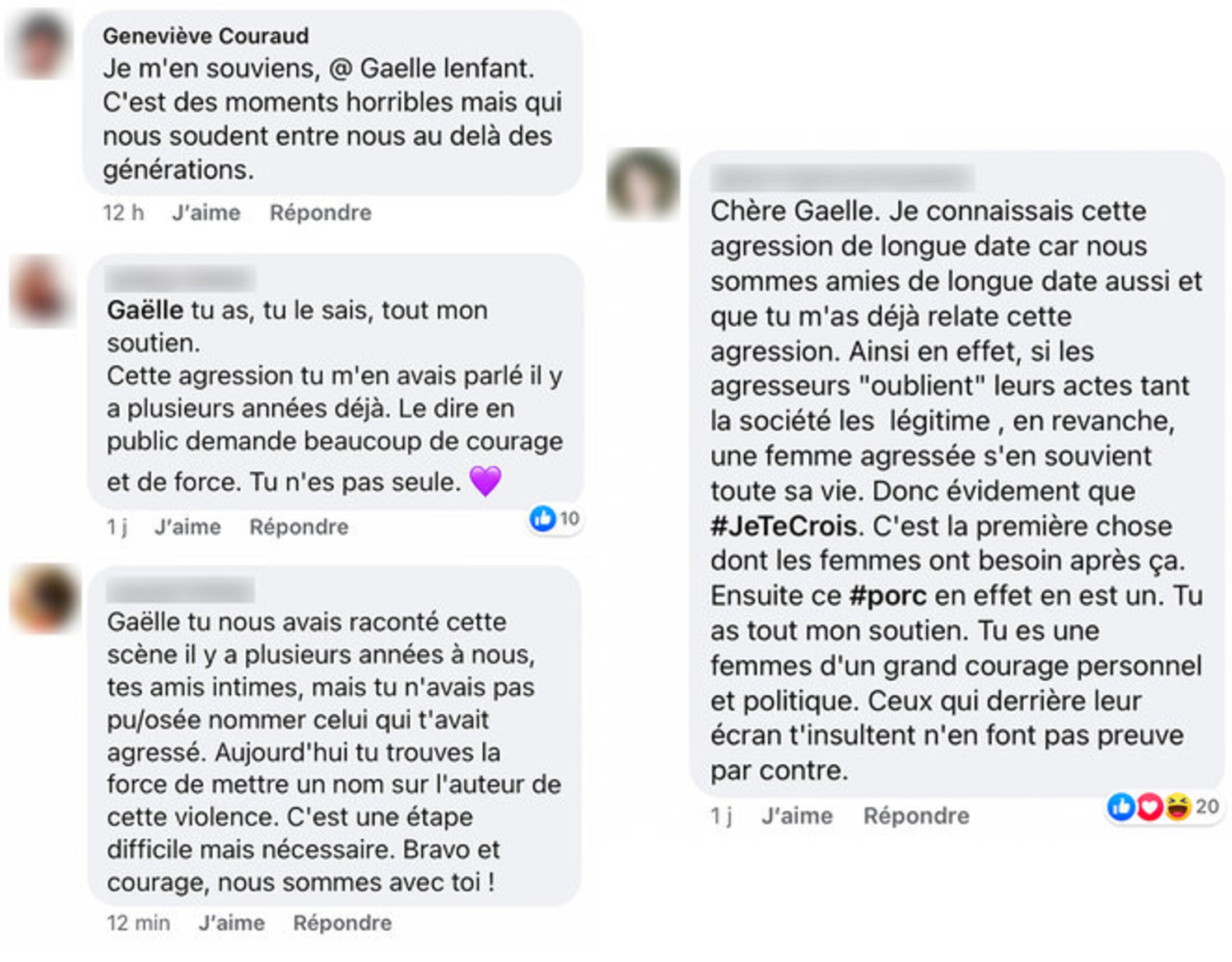

Enlargement : Illustration 1

This Facebook message has since attracted thousands of comments. Many of them support Gaëlle Lenfant. But many, too, are critical, and she has been accused of lying, of wanting to settle scores with a man who has become famous, a man whom some dream of standing in and winning the next presidential election in 2022. Some of the messages were threatening. Mediapart understands that on Thursday April 29th she lodged a formal report over criminal “threats”.

The councillor had been prompted to publish her story by a poster of Zemmour that was – for a brief time – put up in the Cours Mirabeau thoroughfare in Aix (see right).

“At the time I never thought of reporting it. … then he became known. His comments about women in his books and on television chimed with what he had done. But I stayed away from it. Then, with the enormous poster in my city, I needed to say it,” she explained. Caught up in a whirlwind of media requests, all of which Gaëlle Lenfant declined apart from Mediapart's, she added: “I didn't fully realise the media impact or the symbolic impact of what I was doing. When I wrote that post I wasn't thinking of Éric Zemmour the public figure but of Éric Zemmour the person I am accusing today.”

In the comments that followed the post several people close to her – friends and colleagues – stated that the councillor had already spoken to them about this episode.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

When contacted by Mediapart, Gaëlle Lenfant's ex-husband recalled it in detail. “I remember it very well. We were married at the time. It was a Saturday or a Sunday at the end of August in 2005. I was gardening. She called me at the beginning of the afternoon, both panicked and angry. She told me that he had forcibly kissed her.” He added: “I'm not on good terms with Gaëlle and we are divorced. But I know she didn't invent that.”

It is quite common in such cases that the people involved or witnesses do not remember details or dates very well, especially many years later. Gaëlle Lenfant's ex-husband, for example, is sure that the reported events took place in 2005, even though Gaëlle Lenfant “believed” it was 2004. The year 2005 also coincides with articles that Éric Zemmour wrote for Le Figaro from La Rochelle and which have been retrieved by Libération newspaper.

That year also tallies with the recollections of journalist Michel Soudais from Politis magazine who had privately been made aware of Gaëlle Lenfant's story. “His assault was reported to me in 2005 almost at the time that it happened,” he explained.

Gaëlle Lenfant, who was then a Socialist Party (PS) activist in the Bouches-du-Rhône département or county – she has since left the party – had also confided what had happened to one of her closest friends at the time, Hélène Le Cacheux. Now a coordinator for the Parti de Gauche party, she said: “[Gaëlle] first of all told me – fleetingly - that she was in shock. Then, back in Aix, we discussed it for a long time at my place. She kept on repeating: 'I swear to you, I did nothing at all.' 'You know me, I had nothing to do with it.' 'Do you believe me?'”

Over time Gaëlle Lenfant opened up to more people about what happened to her but only privately. “I straight away recognised the facts when I read her post: she had told me about that,” said Geneviève Couraud, a feminist and socialist activist. Gaëlle Lenfant also later spoke with friends about the episode when the subject of Éric Zemmour and his appearances on the television programme 'On n'est pas couché' came up. “She spoke to us about the compliments about her little dress and of a forced kiss,” said one friend, Jean-Dominique, who did not want his full name published. “At the time I must admit to my shame that it didn't shock me … it made us realise that a kiss is also a violation of privacy: that's exactly the point of #MeToo,” he added, referring to the international movement exposing men's assaults and unwanted advances on women.

Those close to Gaëlle Lenfant recall hearing about the episode; no one then thought to report it; the cost of doing so can seem disproportionate, while the facts are often downplayed by those involved.

Éric Zemmour did not respond to Mediapart's questions about this episode in La Rochelle. According to French public broadcaster France Inter, who cited the journalist's “entourage”, Zemmour apparently had “no memory of this scene” and thought that it was a “political affair that comes at a time when everyone knows there are certain hopes surrounding him”.

Éric Zemmour did not respond to Mediapart's questions about this episode in La Rochelle. According to French public broadcaster France Inter, who cited the journalist's “entourage”, Zemmour apparently had “no memory of this scene” and thought that it was a “political affair that comes at a time when everyone knows there are certain hopes surrounding him”.

Gaëlle Lenfant's story struck a chord with Belgian journalist and author Aurore Van Opstal who on April 27th Tweeted: “When I met Éric Zemmour for the first time, within three minutes he was stroking my thigh up to my crotch under the table of the Parisian cafe we were in. Given my past [editor's note, she had been abused as a child] it seemed minor and I stayed in contact with him.” (See Tweet below.)

Contacted by Mediapart the 31-year-old journalist explained that she had spoken “out of feminine and feminist solidarity” after reading Gaëlle Lenfant's post. “I'm speaking out today, too, because feminists have taught us that the private is also political,” she added. She thinks that the ideas that Éric Zemmour has developed in his writing correlate to the very behaviour that she is now attacking. “He is sexist, he defends the patriarchal system. According to him women are by nature emotional and not rational,” she said.

Aurore Van Opstal's involvement with the Le Figaro journalist began when on February 5th 2019 she asked him to give her father a “surprise”; her father is a manual worker born in Charleroi in Belgium on the same day and in the same year as Zemmour and loves “television and media people”. In an email to Zemmour marked “Request for a meeting” she portrayed herself as a “friend of Michel Onfray”, the writer and philosopher. She said she and her father “admired [Zemmour's] work a lot” and suggested the three had lunch. On February 18th Éric Zemmour agreed to meet and according to emails seen by Mediapart suggested that after lunch they all three had a coffee near Le Figaro.

Aurore Van Opstal said that the meeting took place a month later in a café. She claims that Éric Zemmour “stroked my knee with his hand” under the table and “went up to my crotch” while still “speaking to my father” who was sitting opposite him on the café booth seat. “He went up and down twice. I was petrified, in shock, I didn't know what was happening, I'd only known him for three minutes. He was 60 and I was 29,” she explained. The Belgian journalist said that he had “looked” at her and discreetly said “may I?” and that he “continued to stroke me while replying to my father”. Aurore Van Opstal added: “The 'may I?' came far too late and in any case I wasn't able to say anything.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

According to Aurore Van Opstal, her father was unaware of what was going on as they had a discussion about “this and that”. She said that as she had been the victim of child sex abuse - and of violence inside the family – this episode appeared “minor” to her. She said: “At the time I was shocked. Then within a few seconds I told myself it wasn't serious.” She said that she had continued to chat with Éric Zemmour and had even taken a photo of him and her father. When contacted, her father Jean-Paul Van Opstal confirmed the meeting had taken place and stated that he had “not been aware of anything” that had gone on. He said that when he later asked for “news” of the journalist his daughter had dropped “hints”, explaining that Zemmour had been “a little insistent and that he was a man who liked women a lot”. It was only on April 27th this year that she had told her father the full details, just before going public.

The Belgian journalist said that she had later contacted Éric Zemmour herself for professional reasons. On April 19th 2019, when she had written to him for advice about freelance work, Zemmour had concluded his reply: “I'd be delighted to see you back in Paris. Kisses.” On December 2nd 2020 she contacted him for a “short email interview” on “structural negrophobia” and ended the message with “kisses”. The journalist declined and added: “I'm happy dear Aurore to hear your news once again, you disappeared when our conversation was becoming interesting”. Aurore Van Opstal told Mediapart: “At no time did I want to have anything other than an intellectual relationship.”

Over the past two years the Belgian journalist has opened up to several friends and colleagues about what happened that day in the French capital. Two of them have confirmed this to Mediapart. One of her friends, a Belgian academic, said that she had confided in him “when she came back from Paris” and had spoken to him about it with a “certain casualness”.

Olivier Mukuna, a Belgian journalist with whom she has worked, confirmed that she had told him the facts “at the beginning of 2021 … in the course of a conversation”. He said: “She told me that for a long time she had blamed herself or had persuaded herself that it wasn't all that serious. I know her well, she's credible.” The essayist and writer Michel Onfray refused to comment on the substance of the case and issued a statement in which he confirmed that he has known Aurore Van Opstal for several years.

'Ok, you can do your own tie up'

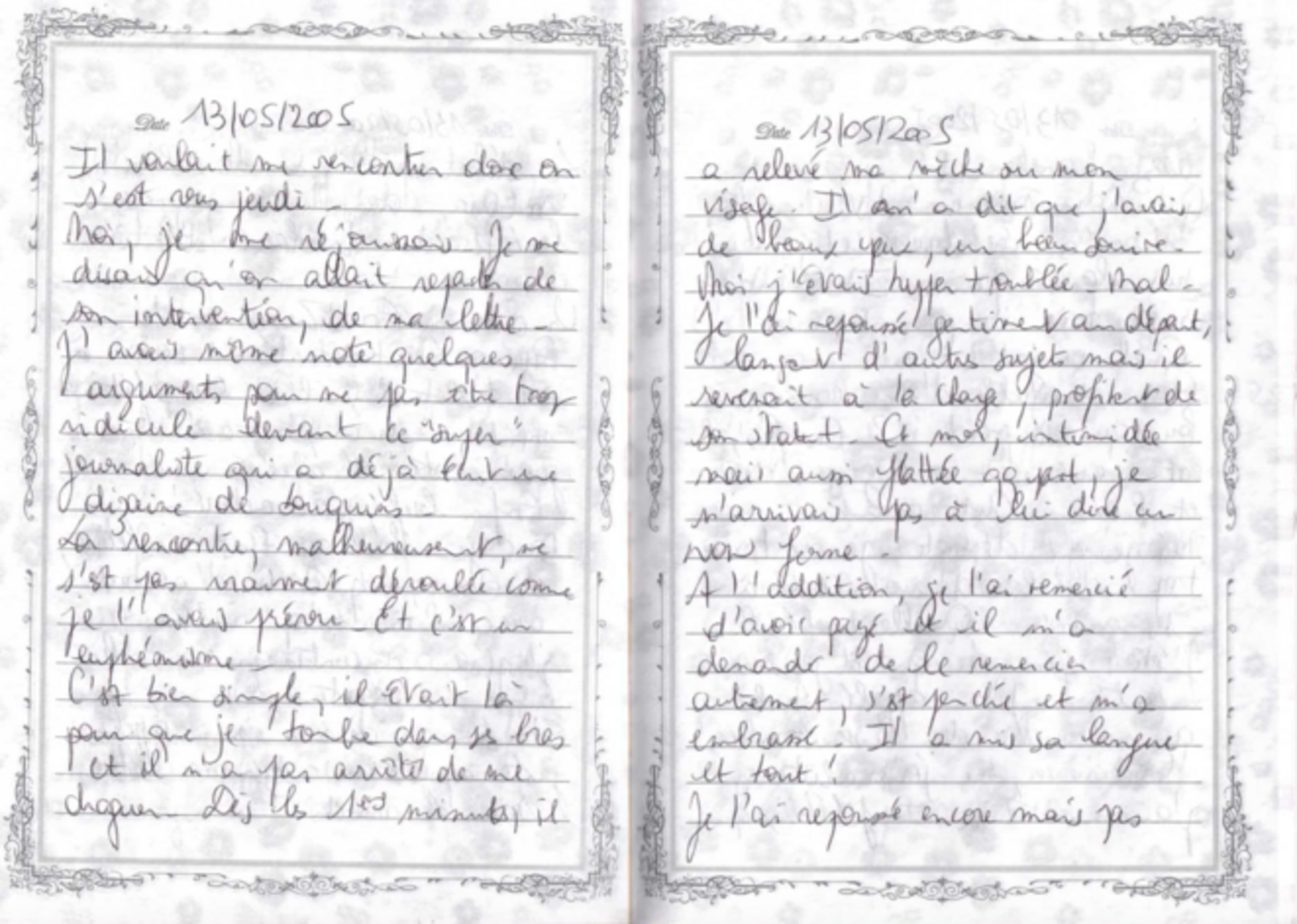

'Anne', a journalist who for professional reasons wants to remain anonymous, reports a similar experience. She initially outlined them to Mediapart on the phone before searching through her personal archives in her stack of private diaries for her comments written at the time.

She described, in some detail, an “extremely unnerving incident” that took place on May 13th 2005. The young journalist had seen Éric Zemmour on the programme 'Arrêt sur images' presented by journalist Daniel Schneidermann, talking about the European Constitutional Treaty, and had recorded her views in her diary. “As usual he was politically incorrect, accusing the journalists of being mad. In short, I loved it!” wrote the young journalist, who says she is still politically on the Right.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

In the diary Anne said that she had subsequently written to Zemmour at Le Figaro. “And indeed the latter called me just after reading my letter, in other words the Tuesday. He wanted to meet me, so we saw each other on Thursday.” She recalls the venue was a café in front of the newspaper's headquarters in Rue du Louvre in Paris. “I was very happy, I thought we were going to speak about his [TV] appearance, about my letter. I had even jotted down a few arguments so I wouldn't be too ridiculous in front of this 'super' journalist,” the young woman wrote in her diary.

“Unfortunately the meeting did not really turn out as I had foreseen,” continued Anne. In her diary she wrote: “He didn't stop hitting on me. … I was really upset. Bad. I tried pushing him back nicely at first … but he returned to the fray, making use of his status. And I was intimidated and also partly flattered, I didn't manage to tell him a firm no.”

Anne later thanked him for paying the bill. “He asked me to thank him in another way, leaned over and kissed me. He put his tongue in and everything! I pushed him off again but not bluntly enough. When we left the café he kissed me again and I let him do it … What a lout! It's unbelievable for someone to be like that. Who does he take himself for? … I am disgusted with myself, I am too weak giving way to his advances ... I was in a panic when I got home.”

The young journalist then confided in several people close to her, including two friends to whom Mediapart has spoken. “She called me as she left and I remember it as if it were yesterday,” recalls Julie, who has remained a close friend of Anne since the two studied together. “She was very shocked. It's very dirty, it's degrading to go to such a meeting which she was happy about - and I was happy for her - about her professional future, and to find yourself with someone who just wanted one thing, to forcibly kiss her,” she said.

Journalist Sylvie Corbet said that Anne spoke to her about it immediately afterwards. “We were shocked. She was so happy to be meeting a writer from Le Figaro to speak about journalism,” she said. “We never thought about reporting it afterwards: we were young journalists and at the time we just told ourselves that we would not go near him again.”

Enlargement : Illustration 6

There have also been question marks over Éric Zemmour's behaviour in several editorial offices in which he has worked. At Le Figaro, for example, where he has worked since 1996, women whom Mediapart spoke to talked of being placed in awkward situations. “There were lots of rumours about him. During my years on the newspaper he was not a man that I wanted to be alone with in the lift,” recalled one journalist who has since left the publication. He was someone whom the “young women on Le Figaro” were wary of, she said.

In 2012 'Jade' – not her real name – began work experience at the paper. She recalls a “very courteous, polite guy” whose behaviour could, however, be disturbing. She has two particular stories in mind. One was in the summer of that year when she took the lift back up to the office where she was working. “He came up with me and immediately stared at my chest in a lewd, obvious manner for some seconds,” she said. “It was the first time that I saw him, I was very uncomfortable, and as soon as the lift opened I quickly left.”

And in June that year Jade was watching the French Open tennis tournament on her computer when Éric Zemmour came up behind her. “He started to watch the match with me even though we didn't know each other. He virtually put his head on my shoulders without touching me,” she recalled. She remembered, too, how it made her feel. “I was again very uncomfortable. It was completely inappropriate, he was a few centimetres from my face, with a view of my chest. It was a very disturbing kind of intrusion,” she said.

Another journalist who worked at the newspaper said of Zemmour: “The overall impression he gave me was that of the crude gentleman, the guy who thinks everything he does is ok, and that he will let you go into the lift first but will look at you from head to toe while doing so and who will make some little remarks.”

This journalist said she had never seen “sexual assaults or targeted and repeated sexual harassment” yet considered that his behaviour “under the cover of gallantry” could be taken badly by some women. She said: “Even so, it makes you feel uneasy, especially when you're a young journalist or trainee, not in a staff job, and you know who Zemmour is and what he represents at Le Figaro.” A third journalist spoke of “barrack room comments” and described Zemmour as someone who was “happy to maintain a sexualised atmosphere”.

In February 2019 Libération newspaper revealed the affair of the Ligue du LOL, the Facebook group of journalists who reportedly harassed feminists via social media. At the time the managing editor of Le Figaro Magazine published a Tweet suggesting that harassment or sexual aggression were the prerogative of certain groups on the Left. “Please @libe, wash your dirty linen in private rather than trying to implicate 'the media' #ligueduLOL,” he mocked in a post on February 12th of that year. A month later Libération published an investigation revealing that some executives at Le Figaro had been accused of sexual assault and harassment.

According to several journalists at the paper Zemmour was one of the names cited behind the scenes. One reporter said the deputy managing editor, Alexis Brézet, had spoken to Zemmour to “caution” him. This episode was never confirmed internally but was much discussed among staff.

When approached by Mediapart Alexis Brézet denied this had happened. “I absolutely deny these allegations. No, Éric Zemmour's name did not 'crop up persistently' in 2019,” he said, adding that he had not called the journalist in to caution him nor “even discussed thus type of issue with him”.

Mediapart understands that one particular episode involving Éric Zemmour also had an impact on several journalists at CNews, the news channel at which the polemicist has worked since October 2019 on the 'Face à l'info' ('Face the news') programme. At the time there was a tense mood at the station. A number of journalists there were critical of the fact that Zemmour had been hired – at the wishes of billionaire owner Vincent Bolloré – given that the controversial commentator had been let go from CNews's predecessor station I-Télé some years earlier.

Inside the new editorial team at CNews Éric Zemmour cut an isolated figure. Police officers were on duty outside the offices to anticipate possible demonstrations against him and a security guard was tasked with escorting Zemmour from the parking lot to the television studio. “He had practically no contact with the journalists. He was in a team on its own with the presenter Christine Kelly, the commentators, an editor and the production team,” said one employee at the station.

The episode in question took place on October 14th 2019, Éric Zemmour's first day on 'Face à l'info'. At the end of the programme the editorialist sent a text message to the programme's editor, a woman whom he had not known until then. “Zemmour called her 'my sweetheart' and asked her in essence to help him adjust his tie the next day,” said one journalist, who said that the editor took this “extremely badly”. The employee continued: “Using these terms was ambiguous and totally inappropriate. She didn't know Zemmour, it was her first day working with him and the context was already very tough. There was already apprehension about working with him and even more so after this exchange.”

When contacted the programme editor said she did not want to comment. “I've always refused to speak about CNews or anyone who works there despite many requests,” she said. Thomas Bauder, the director of news at the station, confirmed the episode but spoke of a “misunderstanding”. He said she had advised the editor to go and see the human resources department. “She went there, they spoke. Afterwards I asked [the editor] if everything was all right and she said everything was fine. For me, that was the end of the matter. For me there's no story,” he said.

Thomas Bauder said that the incident had not resulted in any further action. “I did not call in Éric Zemmour, he's a big boy. I felt that there was a little issue over the story about the tie: I said to Éric: 'Ok, you can do your own tie up. If you have a problem, speak to me about it'.”

When he worked at CNews's predecessor, I-Télé, Éric Zemmour also left painful memories for some staff to whom Mediapart spoke, mostly junior staff who looked after reception and the make-up room.

Make-up artist 'Nathalie' – not her real name – remembers how Éric Zemmour came each Friday to take part in the 'Ça se dispute!' programme. One day she found herself alone with the journalist in the make-up room. “I was 26, I was rather naïve, I wasn't wary,” she recalled. She said that after the make-up was done he had got up and “pressed me against the wall”. Nathalie continued: “One hand was on my arm, and the other above my breast near my armpit.” She said he told her: “Don't you understand that I want to kiss you?” The journalist then “got out his business card” and added: “Call me, we must see each other, I can get you work.” Nathalie said: “I was so surprised that I didn't even slap him or insult him, I just pushed him back and said 'no, that's not right'. He saw from my face that I wasn't expecting that. He didn't insist at all.”

“He's smaller than me so he never dominated me physically and I've always had work, but I understand how he might have a certain influence,” Nathalie added, talking about how he had brandished his business card. She said that she had “torn it up in annoyance”.

The make-up artist later disclosed to colleagues what had happened and told them “not to be alone in the make-up room with him”. Three have confirmed to Mediapart what she said to them. Make-up woman Gwenaëlle Courtois remembers that her colleague had been “very shocked”, “in a bad way and trembling” and “not knowing what to do and who to tell about it”. She said Nathalie had later asked her to “do his make-up when he came because it made her uneasy”.

The programme's stylist, Franck Dell, remembered that Nathalie had been “very unsettled” and “very taken aback”. Another make-up artist, who asked to remain anonymous, confirmed what Nathalie had said and added: “You really had to watch out for him. I know that he didn't behave terribly well, another make-up colleague told me that he had told her she was a real woman because she was wearing heels.”

Nathalie also recalled Zemmour's “unsettling” and “overbearing” behaviour when they did make-up around his eyes. “Rather than closing them he kept on staring endlessly at us, that made us feel uneasy,” she said. Her colleague Gwenaëlle Courtois confirmed: “When Nathalie did his make-up he checked her out. I saw that.”

At the time Nathalie did not want to refer the matter to her superiors as she felt that she had “not been traumatised” by the incident. Franck Dell said: “I was shocked, I told her that she had to tell management about it, that it was not right that a man who has very firm views on couples [editor's note, Éric Zemmour is a strong supporter of marriage] behaves in a diametrically opposed way,” he said. “But I felt that she was uncertain, as you often can be in cases like that, she didn't want to alert people, it's difficult to speak out when you are a casual worker. We had no security. And it was also well before #MeToo.” Gwenaëlle Courtois said that it was an unequal struggle. “It's easy against women who have no power. Because we also risking losing our work,” she said.

However, a member of the production team did hear about the incident at the time. When contacted by Mediapart he said that he had reacted immediately by talking to Nathalie about it. “I asked her if she wanted to report it, if I could refer it to HR management,” he said. “She was so freaked out … she asked me not to speak to anyone, I would have personally preferred for it to have been flagged. But I respected her decision. We did our best to protect her, we found an unofficial workaround,” he said. According to him, Nathalie and another make-up woman this “workaround” consisted of changing the schedule so that she no longer came across Éric Zemmour. “If he was coming in the morning, I booked her in for the afternoon,” he explained.

'He put his hands on my bum'

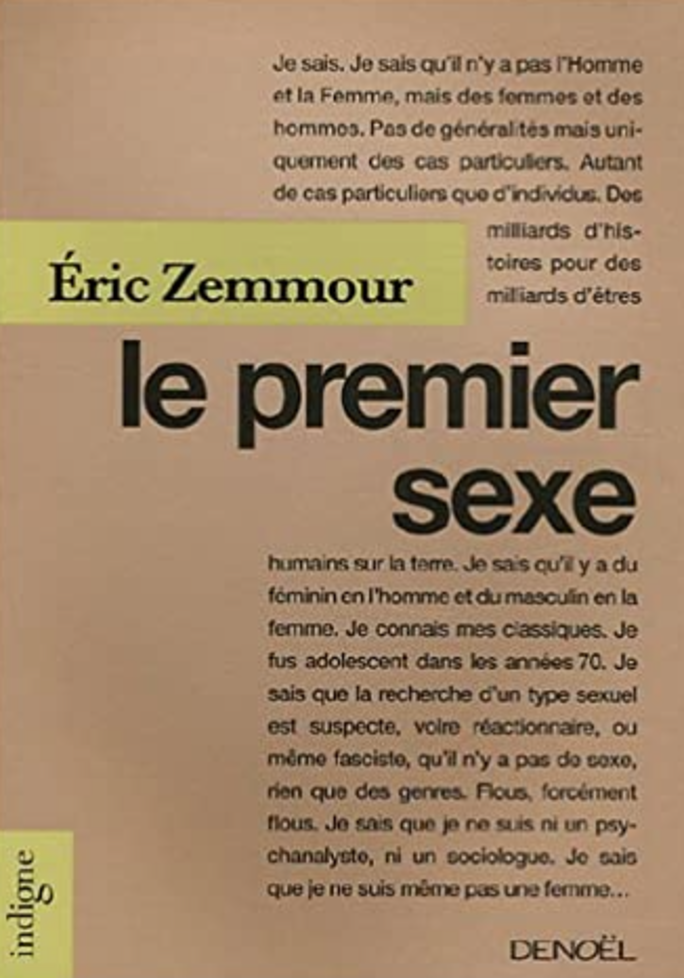

'Celia' – not her real name – also remembers her work as a receptionist at I-Télé at the beginning of the 2010s. “I was very young [editor's note, 22] and at the start I used to discuss things with him. I had read two of his books 'Petit frère' [editor's note, published by Denoël in 2008] and 'Le Premier Sexe' [editor's note, published by Denoël in 2006], and I saw it as an opportunity to speak with someone from the far right,” said Celia, who was a student at the time. She said the atmosphere at the station often made it tough for women. “From that point of view Éric Zemmour blended into the décor. It was part of our daily life, especially with the politicians. It was a quite a generalised atmosphere. The distinctive thing about Zemmour was that he tried to break the boundaries, the physical distance … he'd sometimes come very close to say hello,” she said.

The receptionist remembers the occasion on which she felt that Éric Zemmour “went too far” in his actions. It was at the start of the 2010s and he had arrived one day in the entrance door to the station's offices in the Montparnasse district of Paris. Celia, who hesitated a great deal before talking about the incdent, said that he had given her a “kind of hug” and that he had “put his hands on my bum”.

After this incident she said she was “not happy” on Fridays when there was a risk of coming across him in the corridors. “I used to hope that he'd record [the programme] at another time. I had knots in my stomach,” she said.

But at the time there was no question of Celia reporting this to her superiors. She was “sure” that she would have been “removed” from the site. She also feared that news of the episode would have got out and that “it would have been the subject of jokes, that would have been degrading” she said. On top of that, she added: “I was so ashamed. And I felt responsible. Because I had spoken to him before, even laughed with him.”

Years later, that sense of responsibility has still not quite gone. At the time she had confided some details to a few colleagues. A fellow receptionist 'Marie' - not her real name - said: “She told me that there had been an incident with Éric Zemmour.” Stylist Franck Dell also said Celia had spoken to him about it “over a cigarette”. He said: “She told me that he had behaved lewdly towards her.”

Questioned about all these reports, neither Éric Zemmour not CNews's press office responded.

The essayist and polemicist has been accused many times over the years of sexism and misogyny. He rejects the very term “sexism”, a concept which he considers to have been a “feminist frenzy for forty years”, just like “racism”, and he sees himself as “not at all misogynistic”. In any event, his media appearances and his writing are steeped in deep-seated anti-feminism, sexist stereotypes and repeated attacks on women.

In 2017 the journalist Gaël Tchakaloff felt the fierce consequences of this when Zemmour said to her on television: “I know politicians a bit better than you but I don't sleep with them.”

It is an argument that he repeats in his books. “The law on equality has decentralised the political droit du seigneur, overloading candidate lists in municipal and regional elections with spouses and mistresses,” he wrote in 'Le Premier Sexe'. Moreover, he considers that the number of “women politicians, of national stature, who have not been in the arms of one of the three French monarchs of the last thirty years (Giscard, Mitterrand, Chirac) [editor's note, the three presidents Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, François Mitterrand and Jacques Chirac]” could be counted “on the fingers of one hand”.

In 2014 his attitude towards two female commentators in the studio of the Swiss channel RTS was revealed by the cartoonist who sketches drawings live on the programme (see the cartoon below). To one of his fellow commemorators who contradicted him saying 'No, that is Mazarine Pingeot” Éric Zemmour retorted “Oh yes, well you're all the same anyway! You say the same thing!” Other comments followed, such as “That's going to please Miss”; “You are in fact more limited that I thought”; “You really believe you're more intelligent than the past?” and so on. To the question “Do you think that male chauvinism made men and women happier than today?” he instantly replied: “Yes.” (see the video from 51 minutes 30 seconds).

Enlargement : Illustration 8

In 2013, interviewed by presenter Ruth Elkrief on BFM-TV news channel, Zemmour argued that “in those environments where there is real power there are no women” because they “don't represent power”. He said that “power evaporates when they arrive” (see below).

In 'Le Premier Sexe' he mocks what he calls a “female paradox”: “Women drive now that speed is restricted; they smoke when tobacco kills; they gain equality when politics no longer serves much purpose; they vote for the Left when the Revolution is over … They don't destroy, they protect. They don't create, they maintain. They don't invent, they conserve.... And in feminising themselves men become sterile, they abstain from anything bold, all innovation, all transgression.”

In his 2014 book 'Le Suicide Français', published by Albin Michel, he argues that men need to “dominate to reassure themselves sexually”, while women need to “admire so they can give themselves without shame”, to “demand the protection of their husband”. And that “fathers” were able to “contain the consumerist impulses” of women before “consumerist propaganda undermined the traditional culture of the patriarch”.

In his writings and television appearances Éric Zemmour always develops the same theory: that the “feminisation of society” leads to the “collapse of society” because it “rejects violence” and “thinks that violence is bad”. On the contrary, Zemmour argues, “the values of virility defend a society better” and “man's violence” is also “protective of society” (see this CNews video).

He criticises laws which have reinforced the crime of sexual harassment and mixed up seduction with sexual violence. “Man must no longer be a predator of desire,” he writes in 'Le Premier Sexe'. “He must no longer chat up, seduce, hustle, attract. All seduction is likened to manipulation, to violence, to coercion … Photographs of naked women are banned in the factories as are smutty jokes at the office. Veiled reverences, hints, seduction, desire. It's the monstrous child of Tartuffe [editor's note, the eponymous main character of a play by Molière] and [editor's note, writer and philosopher] Simone de Beauvoir. Man no longer has the right to desire, no longer the right to seduce, to chat up. He must only love.”

In the course of a passage in 'Le Suicide Français' in which he analyses a 1973 film, Éric Zemmour writes: “When the young bus driver slips a lustful hand on a charming female bum, the young woman doesn't make a complaint for sexual harassment. Trust prevails.”

At a time when the #MeToo movement has caused a shockwave, and on precisely the theme he raises in his books, Éric Zemmour has criticised the way that victims of sexual violence have felt liberated to speak out. On Europe 1 radio he said it was a form of “denunciation” whose equivalent movement in World War II would have been '#dénoncetonjuif' ('DenounceYourJew'), a reference to the French equivalent of #MeToo which is #BalanceTonPorc ('#SquealOnYourPig').

His target is United States where he claims the “castrated man was born” at the when women “obtained equality, respect, lack of differentiation, laws against sexual harassment, the sharing of roles in the house and an entry in massive numbers, and at the highest executive levels, into professional life,” he writes in 'Le Premier Sexe'. While supporting an open letter signed by actress Catherine Deneuve – who attacked the “puritanism” of the #MeToo movement – Éric Zemmour defended on RTL radio what he considered to be “customs of French gallantry” and the “mark of a way of life”.

Since then he has constantly criticised what he calls the “double standards” in the #MeToo movement which he says only targets “white males”. He said on CNews in 2020: “There's obviously no reason to be in favour of violence against women, that must obviously be savagely punished, but I don't see why you wouldn't punish others.” He cited in particular infanticides which he said were “in the most part” carried out by women. He denied the existence of what he termed the “much talked about femicide”. He said: “Men don't kill them because they are women, in general they kill them because they are their wives and they are leaving them.”

The commentator has also highlighted sexual and sexist violence carried out by men in the “suburbs”, which in France are often poor neighbourhoods where people from immigrant backgrounds live. On BFM-TV in 2018 he said: “I know young women who don't dare to go out in a dress, who don't dare to go out in a skirt because they get spat on in countless neighbourhoods, no further away than some Parisian suburbs I know.”

-------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

-------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter