The gap that separates the 'MeToo' revolution in the United States from its 'Balance Ton Porc' ('Squeal on your Pig') counterpart in France could be summed up by one date, that of January 9th, 2018. On that Tuesday one hundred women, among them the actress Catherine Deneuve, published an op-ed in Le Monde which described the #MeToo as a “campaign of denunciation”. On the other side of the Atlantic, meanwhile, a video was in the process of becoming massively popular; it featured the powerful speech given by Oprah Winfrey at the Golden Globes awards ceremony the night before. The woman who became the first black female presenter to make it big on US television had just announced that a “new day is on the horizon” for women. “This year we became the story,” she declared.

In France the “Deneuve article” was portrayed as defending the “freedom to pester”. In the United States The New York Times stated, quite factually: “Catherine Deneuve and Others Denounce the #MeToo Movement”. Six months later and The New York Times highlighted the contrast in the reaction in the US to #MeToo and the reaction in France to the complaint made by actress Sand Van Roy against French film director Luc Besson. “... in France, few celebrities have spoken up in support of Ms. Van Roy, and the initial reports about Mr. Besson have not led to a similar housecleaning in the entertainment industry,” the newspaper noted.

How can one explain such a difference between the two countries? What in France has stopped the #MeToo movement from having the same impact as in the US? Mediapart has posed this question to women who have followed or been involved in this movement: activists, academics, heads of associations and medical experts.

The French historian Laure Murat, who teachers at the University of California (UCLA), sums up the answer in one phrase: “In the United States there was reactivity, in France there was reaction.” According to the people to whom Mediapart spoke, in France the #MeToo movement quickly came up against a wall of silence, a lock-down on information, a “desire to stifle” and “denial”. This can be measured through a series of episodes, both large and small in scale. They include the 'Deneuve article' and the comments in the media made by two of its signatories (“You can orgasm during a rape” and “My great regret is not to have been raped [to show that] one can get over rape”). Then there was the virulent attack by the philosopher Raphaël Enthoven speaking on the platform of the summer conference on feminism organised by the government minister Marlène Schiappa. Another episode was the pinning of white ribbons on guests at the French 'Oscars', the César awards, a far cry from the powerful speeches at the Oscars themselves.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

In France a minister who was the subject of a rape allegation – budget minister Gérald Darmanin – got a standing ovation in the French Parliament; a star actor who is accused of rape and sexual assault made the front page of a daily newspaper under the headline “extravagant”; a director who has won Oscars and who has been the target of several rape accusations was honoured by the Cinémathèque French film institute; a rapper who sang “I want to give you an abortion with an Opinel [editor's note, a make of knife]”, and “You're gonna be a Marie Trintignant”, a reference to the actress killed by her pop singer boyfriend in 2003, was glorified in the media and acquitted by the justice system; and a presenter, Jean-Pierre Elkabbach, and his guest discussed on live television their desire to “slap” a feminist activist. Meanwhile victims have been described as “sluts” or “prostitutes”.

“In France #MeToo is still a subject for debate, people are invited to be 'for' or 'against', the two opinions are put on the same footing. In the United States, there is no longer debate on the principle of #MeToo, but on its limits,” says Alice Coffin, a feminist activist and co-founder of the association of lesbian, gay, bi and trans journalists AJL, highlighting a major difference between the two countries.

She has worked for the last six months in the United States on the different media treatment of LGBT issues in the two countries and says France is the polar opposite of the US. “Lots of harassers stay in place even though their harassment is known about. The idea lingers that violence against women is not serious, it's also the permanent subject of jokes,” says Alice Coffin. “In the United States Jean-Pierre Elkabbach would have been sacked in two seconds,” she said referring to the presenter mentioned earlier who discussed slapping activist Caroline De Haas. This “French wall” goes back to problems with other minorities such as the LGBT and black communities, she says. “Which is striking because women are not a minority in terms of numbers,” says Alice Coffin.

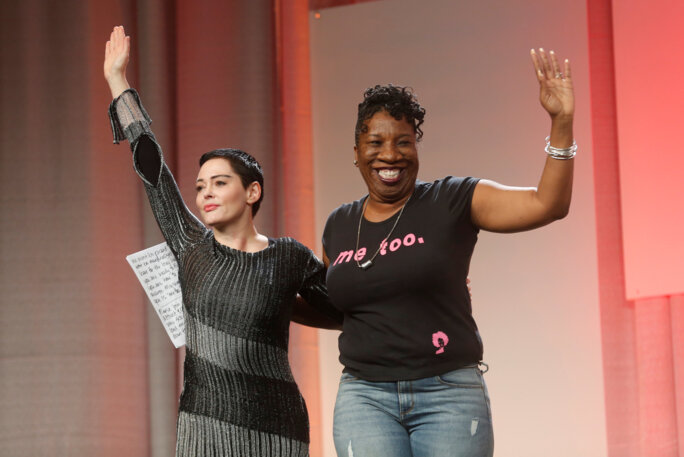

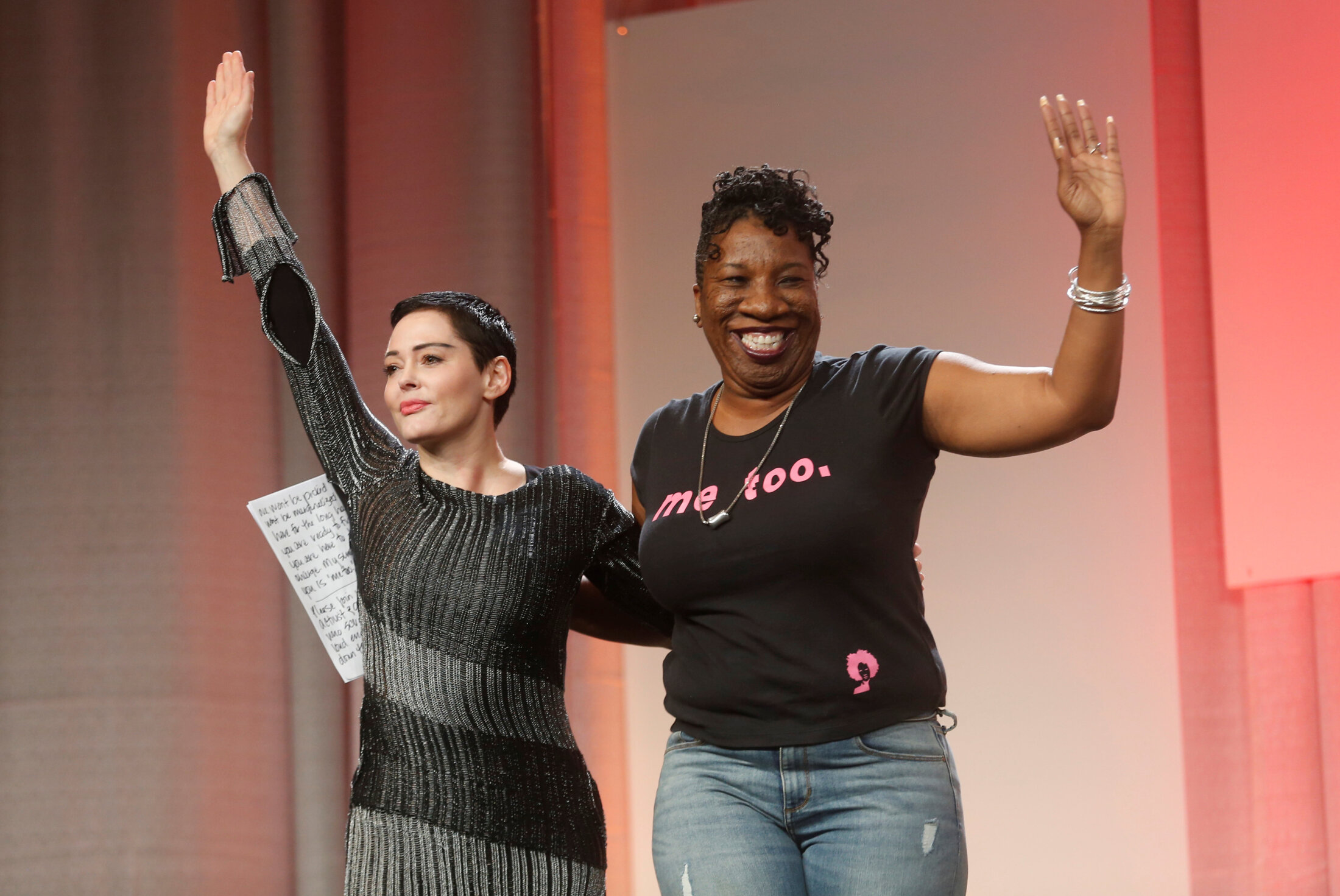

Ketsia Mutombo, aged 24, from the women's collective against cyber harassment, Féministes contre le Cyberharcèlement, points out that the French debate is “personalised around two white figures, the actresses Rose McGowan and Asia Argento” and is very different from the diverse discussion seen in the American movement. The debate in France also quickly “centred on men and the issue of masculinity” she said. “In the debates it was felt necessary to point out that this is violence committed by both sexes, even though the majority is carried out by men,” says Ketsia Mutombo.

In the United States the list of personalities publicly accused of sexual violence grows every day; more than 240 so far, against around 30 in France. In other words 7.5 times more. The difference cannot simply be explained by the fact that the population of the US is five times greater than France. Nor by the fact that, as some would claim, sexual harassment is simply more prevalent in the United States.

Certain sectors, such as the media and the world of culture, have been relatively spared by the #MeToo shockwave. Though in the US a series of star journalists have had to resign - at CBS, NBC and Fox News in particular – in France the positions of two journalists whose behaviour has been challenged, Frédéric Haziza and Éric Monier, have not been under threat. Haziza, it is true, has not been retained by the LCP Parliamentary television channel. But he has continued as a presenter at Radio J and has merely been cautioned about his behaviour after an investigation into sexual assault ended with no further action being taken. Monier, meanwhile, was promoted to editorial director at the commercial television station TF1 despite 13 witnesses describing his behaviour in the press and after a formal complaint for “sexual and psychological harassment” which was not pursued because the alleged offence had taken place too long ago.

In the art world a movement began following the Harvey Weinstein affair, after the resignation of the influential publisher of the magazine Artforum, Knight Landesman, who was the target of nine complaints for harassment. An open letter was published by 7,000 women working in the arts which attacked the prevalence of sexual harassment. “A group discussion started on sexual harassment under the hashtag #notsurprised,” recalls the art historian Élisabeth Lebovici. A year later she is saddened by the “silence” in te sector “including in art schools”, and especially after the “shock of the op-ed [editor's note, by Deneueve and others] signed by several artists, art critics and curators”. But she is not terribly surprised. “It's a domain that happily describes itself as progressive, but that in no way stops the abuses of power and it hasn't helped people to speak up,” says Lebovici.

The gap between the two countries comes from two different conceptions of the world and two different mentalities, in particular when it comes to morals. The relative dissent in France over the #MeToo movement is part of a double 'French exception' that is systematically invoked to justify such resistance: a supposed tradition of “French-style seduction” and the spectre of “informing” or denunciation.

'Gallantry' 'a society of informing' and a 'culture of secrecy'

After the Weinstein affair the actress Isabelle Adjani mocked the three French 'G's': gallantry, ribaldry (grivoserie in French) and crudeness (goujaterie in French). The idea of the “seducer” has often been raised when personalities have been under the spotlight for their behaviour. This was the case with green MP Denis Baupin, who pointed to “misunderstood libertinism” when he was accused of sexual misconduct, and also with the former head of the International Monetary Fund and one-time presidential hopeful Dominique Strauss-Kahn, who was portrayed as a “libertine”, a “charmer”, a “lover of women” and a “ladies' man” after revelations about his behaviour towards women. Another example was film-maker Claude Lanzmann, whose obituaries were full of hints, contained in phrases such as “impetuous and impassioned seducer”, “gallant and seductive towards women” and an “insatiable seducer”, who “loved women”. It is also precisely the tone of the 'Deneuve article' which lays into American “puritanism”.

The American historian Joan Scott, who specialises in French history including social and gender issues, believes that the authors of the 'Deneuve' article “entirely missed the point that #MeToo was a critique of the use of sex as an instrument of male power. This not about puritanism, but about men demanding sex in exchange for women getting jobs. It was not ‘puritanism’ but a critique of power that was at issue,” she told Mediapart.

Joan Scott has discussed this idea of a French 'exception;' in her works. “Over the years, French national identity has been identified with seduction, with what some self-defined feminists have referred to as 'consentement amoureux', the willing subordination of women to men in the 'game' of love,” she says.

“I argued in my article on French seduction theory that an influential group I called 'aristocratic republicans' had re-purposed a long held stereotype of French culture—the one that insists that there is no domination in the game of seduction, that 'the French' (a nation, a culture) like 'sex' (in contrast to puritanical Americans) - in order to offer a vision of the inequality of differences (not only sex, but race and religion) that was benign and acceptable.”

Has this well-known “French exception” put France ten years behind in relation to how its society regards this issue? That is the view of essayist Laure Murat, who sees in it a “form of tackiness disguised as a libertarian provocation” and is in particular “the mark of a country which has given up on refection” and instead prefers to “hurriedly sweep the dust under the carpet”.

Enlargement : Illustration 3

The idea that #MeToo adopts the methods of “denunciation” also recurs frequently in French debates on the issue, bringing with it a deep-seated fear of war-time collaboration. The polemicist Éric Zemmour even suggested that #BalanceTonPorc ('Squeal on your Pig') would have had as its equivalent “Dénonce ton Juif” ('Denounce your Jew') during the Nazi Occupation. This argument that the #MeToo movements risks pushing us towards a “society of denunciation” has been picked up by President Emmanuel Macron and finance minister Bruno Le Maire, who explained – before back-pedalling – that he would not report a political leader for harassment because “denunciation” was “not part of my political identity”.

The feminist activist Caroline De Haas, who heads a company offering equality training, sees in this approach the signs of a persistent “culture of secrecy” in France. It is a culture which shows an aversion to whistle-blowers, and does not distinguish between “informing” and “denouncing”. Anne-Cécile Mailfert, president of the women's foundation the Fondation des Femmes, notes with irony that this fear of informing is not apparent when it comes to other crimes and offences. This criticism of the #MeToo movement is a “false excuse” she says. “We're in a system that protects men,” Mailfert adds, referring to the ovation in Parliament received by budget minister Gérald Darmanin three days after an investigation into alleged rape – since dropped - was opened into him. “Those who have 'fallen' after #MeToo were those who didn't have any power,” she says.

Beyond these cultural and historic factors, American society is also more sensitive to issues of sexual violence. The main reason for this is education. On American campuses the issues of harassment and discrimination are the subject of meetings and training and also official safeguards. On each campus there is a 'Title IX Officer' – named after legislation dating from 1972 – whose job it is to deal with warnings and alerts flagged by students.

Joan Scott says that “gender studies” have also had an important impact in universities. “Since the 1980s, these programs have educated generations of young women (and some men) about inequalities of power among women and men,” she says. “The graduates of these programs are everywhere: in education, in the media, in the arts, in science, even (though to a lesser degree until now) in politics. There has been no comparable educational development in France. There are very few gender studies programs anywhere at major universities, so the kind of public education (conscious-raising) hasn’t happened in France the way it has in the US.”

Enlargement : Illustration 4

Another explanation lies in the respective judicial arsenal of the two countries. In the United States there are more major laws defining and punishing harassment, though Laure Murat nevertheless points out one major failing in the application of the law in the US. “For the most part the law – or rather the way that it is interpreted and put in practice in the form of administrative and policies and rules – doesn't protect people but institutions,” she says. Businesses and universities prioritise “liability management”. In short, the decisions are still guided by financial interests.

Even though Emmanuel Macron says that France “anticipated” the #MeToo earthquake and that he has made male-female equality his presidency's “great cause”, the public authorities in France, meanwhile, do not seem to have got the measure of the phenomenon. Anne-Cécile Mailfert says that while the movement has produced “real change” among women, society itself has not changed and the “public authorities have not been equal to it”. She says: “The 2019 budget dedicated to male-female equality is the same. It's as if nothing had happened. Women are told 'go on, speak out!' but they don't put extra resources at the disposal of associations, into the training of police officers. It's as if there were a cholera epidemic in which they weren't offering any more vaccines. If there had been a 40% increase in the number of cases of armed robberies they would have released the resources.”

Three months before #MeToo began the junior minister responsible for equality, Marlène Schiappa, saw her budget cut by 2.5%. Though she later got a symbolic extra advance payment, her budget remains the smallest among the French state and ministries, representing just 0.007% of the total budget expenditure. By way of comparison Spain spends three times as much and Canada 14 times as much in proportion to its population, without even considering regional budgets, according to analysis by Europe 1 radio.

“Women trust the associations first and foremost, they are the first stop, they must have more resources,” says Anne-Cécile Mailfert, whose foundation has raised 250,000 euros this year. This enabled it in particular to help the association against violence to women in the workplace, the AVFT. Created in 1985, the AVFT and its five legal experts have been swamped by the demand and it had to close its telephone helpline between January and June this year. “We still feel the #MeToo effect today,” says the AVFT's manager Marilyn Baldeck. “Since our phone exchange reopened it's been a constant stream. Our team are at the end of their tether. For us the situation has got worse.”

The association, which is the main recourse for many victims, today survives thanks to modest payments from local authorities. For its annual grant of 235,000 euros has not gone up, unlike the feminist collective against rape, the CFCV, which saw a modest increase of 60,000 euros in its budget in 2018.

'We're sending women to smash themselves against a judicial brick wall'

The problem is also a legal one. “In terms of the compensation and the punishment, nothing has changed,” says Marilyn Baldeck. “It remains very hard to get through the sieve of the prosecution authorities and the aggressors have a lot of legal tools to defend themselves in France.” In 2011 the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) criticised France over an article in the country's criminal code on the crime of slander.

Anne-Cécile Mailfert says: “We're saying to women 'Stop using Twitter you have to report it!' They call the associations, make a complaint, and the legal system responds by dismissing the case. Getting a conviction remains very difficult.” As far at the head of the women's foundation is concerned “the new stage of #MeToo is to mobilise society”. According to a study carried out by the foundation in September, which gathered evidence from 1,169 victims of sexual violence, more than 70% of those questioned said they had “little” or “no confidence” in the police and legal system. Meanwhile 55% of those who had contacted the police had found the experience “unsatisfactory”.

“The majority of women are convinced that their complaint is pointless. Two thirds abandon it after the first meeting or the filing of the complaint,” says lawyer Élodie Tuaillon-Hibon, who has taken up numerous cases involving victims of sexual abuse, including in the Gérald Darmanin case. She also attacked the impact of the government's announcements on the issue. “No, we weren't ready before other countries as Emmanuel Macron said, no it hasn't changed,” she says. For the lawyer, who quit her profession last month, the Darmanin affair and the fact that the case was dismissed – though that has been appealed – was the “straw that broke the camel's back”.

Enlargement : Illustration 5

A year after #MeToo, Élodie Tuaillon-Hibon thinks that “we're sending women to smash themselves against a judicial brick wall” because “it often turns against them with slander complaints”. She still thinks that women should be encouraged to make complaints “but we mustn't lie to them about the fact that it will be difficult”. Especially, she says, as in France “the paradigm is that the woman is presumed to be consenting and the man is likely innocent”. She would like a system which “preserves the presumption of innocence but which also takes account of the victim's word, which is allowed under the Istanbul Convention [editor's note, on preventing and combating violence against women and domestic violence] ratified by France in 2014, which could be applied from now on”.

The psychiatrist Muriel Salmona, president of the Mémoire Traumatique et Victimologie association which carries out education and research on the psychological consequences of violence, also criticise the assumption that victims of sexual violence are not telling the truth. “Not only does the culture of rape remain very present in our society, but we worry more about the impact of those accused than the victims, who are often accused of having provoked it,” she says. Salmona refers in particular to a study at the end of 2015 involving a thousand people which shows that, for a quarter of French people, the mere fact of walking along the street in a very short skirt or showing cleavage can constitute a reason that lessens a rapist's responsibility. The same applies if the victim had shown a provocative attitude in public. She also points to the fact that many people still think that if a victim yields when under duress it is not rape.

As a result of the lack of protection and the difficulty in getting convictions, Muriel Salmona feels that “we're abandoning the victims”. The medical world shares part of the responsibility for this, she says. “Doctors and psychiatrists are the first recourse for victims but it's also one of the professional environments where there is the most sexual violence, and it remains affected by a strong [sense of] machismo.”

Another reason why France is behind the US on the issue is to be found in the way the media has handled the #MeToo debate. The historian Laure Murat points the finger of responsibility at a section of the media which offers a “caricature” of the debate and a “binary” choice and which has “deliberately stifled the issues under false controversies”, reviving the “war of the sexes”. Journalists today still remain under-informed about the issue of sexual violence.

The activist Alice Coffin says that in many debates the main protagonists are not invited to discuss the issue around a table, and that the #MeToo phenomenon has not led to an increased media profile for feminists. Ketsia Mutombo says: “When you're a feminist activist you're invited into the studios to react to or take part in a clash, rarely to get involved in the fundamental problems.” Caroline De Hass sees this as part of the way the media works, to create controversy. “The reactionaries are invited to create a buzz and it works! One Éric Zemmour who makes racist comments is worth more clicks than a feminist activist,” she says. De Haas, who was an advisor to the former women's rights minister Najat Vallaud-Belkacem, says she is struck by the “level of ignorance on sexual violence in France” in contrast to the “structured talk of American personalities (actresses, feminists, journalists etc) who have understood what the relationships of domination, rape culture and the aggressor's strategy are.”

Enlargement : Illustration 6

This problem is also linked to the weakness of the feminist movement in France. “In the United States feminists are received at the highest levels, are recognised and are able to change things. In France the feminist movement is very focussed on the ground, looking after victims and is doing a remarkable job, but we're lacking political action in the movement which is not very visible today,” says Caroline De Haas. “Ask people in the street to name a single feminist.”

Nonetheless the French backwardness on the issue must be put into context. If France is lagging behind, the United States is an exception, and is ahead on the issue partly because of a particular context – the Trump presidency. “I do think the role of the media has been very important, but I'm not sure that if Trump weren’t president there would have been the same reaction,” says academic Joan Scott. “One of the reasons for #MeToo had to do with the fury of so many women at the election of Trump—now the sexual harasser in chief!! MeToo seems to me, at least in part, a displacement of that anger onto the behaviour of others who were equally guilty, but perhaps more 'vulnerable'.”

Everyone in France to whom Mediapart spoke also agreed that the #MeToo movement had produced a deep upheaval in society. French society before the Weinstein affair is not the same as French society in the #MeToo world.

“We haven't had a broad social movement like in Spain or the United States, and there is some strong resistance, but #MeToo has radically changed things and is still making waves,” says Caroline De Haas. It is something she says she has noticed in her daily life “for example in evenings for mothers at the primary school” and also in her work where the number of calls to get involved in the specific issue of sexual harassment has increased. “The atmosphere, the interest and the respect for the issue have changed. Women are displaying more interest in their involvement in these courses, men are more aware and we have fewer irritated 'resistors' than before. In particular a lot more cases are coming to us from inside companies.”

Ketsia Mutombo, from the collective against cyber-harassment, also sees two other benefits in the #MeToo movement. “We've seen that action can come out of the digital [world], start a conversation, bring together hundreds of thousands of people, create solidarity at the other end of the planet, and that is continuing with the hashtag #WhyIDidntReport.” And for the first time, she says, “we've shown that rape culture crossed every background, that sexual violence was not the sole reserve of men of colour, poor men, nor just the guy who whistles you at the Stalingrad metro [editor's note, station in Paris] but also of privileged white men.”

More broadly, Alice Coffin says that the movement that followed the Weinstein affair has helped to “reinforce and legitimise the struggle inside companies against the exploitation, domination and harassment of staff”. She gives the example of the historic strike by workers at McDonald's in the United States. “Being labelled #MeToo allows you to be heard more,” she says.

“#MeToo has infused society for months,” says lawyer Élodie Tuaillon-Hibon. She has noticed this among some of her fellow male and female criminal lawyers, where the debate has “moved on a bit”, and also in her own practice where the demand for cases involving sexual violence has almost tripled in number. “Many women have come in less afraid that they won't be believed,” she says. Some, says Élodie Tuaillon-Hibon, “cry with relief that at last they feel they can say what they've gone through.” Others come to get information on the legal risks if they publish their story. One case involved a woman of 81 who had been held prisoner in a cellar by a man when she was just 14. After years of silence she said: “In fact, I believe that afterwards he raped me.” She had never talked of it before.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------

If you have information of public interest you would like to pass on to Mediapart for investigation you can contact us at this email address: enquete@mediapart.fr. If you wish to send us documents for our scrutiny via our highly secure platform please go to https://www.frenchleaks.fr/ which is presented in both English and French.

----------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter