Emmanuel Macron is the secret political son of Valéry Giscard d’Estaing or VGE as he was widely known. Indeed, the homage that President Macron paid to his predecessor, who was president of France from 1974 to 1981 and whose death at the age of 94 was announced on December 2nd, was not just pure rhetoric. “His seven-year term of office transformed France,” said Macron. “The direction that he gave France still guides our way.” Meanwhile government minister Marc Fesneau, of the centrist MoDem party, described VGE as “a legacy and an ideal”.

Of course Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, a haughty figure convinced of his unsurpassable superiority, always took great care never to have either an heir or a successor. But with a gap of nearly fifty years between their political heydays, the similarities and continuities between the two men are striking.

That is not just because they are the youngest men to have been elected as president of the Republic, Macron at the age of 39 and Giscard at 48. Both are also products of the École nationale d'Administration (ENA), a finishing school for the country's elite, and both served as ministers in the prestigious Ministry of Finance and the Economy. They also both came to power with the backing of parties outside the mainstream. In Giscard's case it was the Républicains Indépendants, basically a rehash of the old Popular Republican Movement which existed in the 1950s and 1960s, and which carried little weight against the established Gaullist party of the day, the Union pour la défense de la République (UDR). Meanwhile Macron's new La République en Marche (LREM) emerged out of nowhere.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Both men came to power in an unorthodox way, in a form of political breaking and entering. In Giscard's case it resulted from treason; treason committed by Jacques Chirac who scuppered the presidential aspirations of former prime minister Jacques Chaban-Delmas when he and 42 other figures on the Gaullist Right rallied behind Giscard. Macron found his way to power through what he himself called a “hold up”; he renounced François Hollande, the president under whom he had served as a civil servant and minister; the campaign of his main rival François Fillon was sunk by a Parliamentary payments scandal; and he rallied to his cause the veteran centrist politician François Bayrou (who had started his involvement in politics back in 1978 as a young supporter of Giscard).

VGE's stated, centrist aim was to “reunite two out of three French people”. Macron came up with what became a trademark phrase that reflected his attempt to balance competing arguments and build a centrist block between the far right and the hard left: “En même temps” or “at the same time...”. François Bayrou, who represents a link between these two different eras, neatly summed up what is essentially the same project: “Politics is not about the clash of two irreconcilable blocs, but about a centrist majority going beyond them.”

More fundamentally, the two men had the same liberal, European and 'modernising' political programme. And both portrayed themselves as a face of change against an out-of-date and tired political system.

Giscard promised “real change and rejuvenation” or, better still, a “progressive liberal society”. He took advantage of the quickening changes taking place in a France stifled by a mummified Gaullist government that had run out of ideas. If one looks back at the figures from the Gaullist UDR at the time - Pierre Messmer, Alexandre Sanguinetti, Maurice Couve de Murville, Alain Peyrefitte, Michel Debré – one sees an old and reactionary guard blind to the changes taking place in French society.

Emmanuel Macron's promise when he became president in 2017 was more or less identical. The Socialist Party (PS) had become a political zombie, the right was tearing itself apart, there was a sense of inertia and conservatism that stemmed from constant failures, and society was keen to turn the page. In this respect the situation in society, the campaign commitments and the political programmes of these two men were very similar when they entered the Élysée.

It is there that the two paths diverge.

After his election win Emmanuel Macron took part in a royal march at the famous pyramid at the Louvre Museum in Paris, already obsessed by a “Jupiterian” demonstration of the top-down nature of the presidency. He embraced in advance all the abuses that the Fifth Republic's system offers. In contrast, the newly-elected Valéry Giscard d’Estaing chose to go by foot along the Champs-Élysées, a move seen at the time as an extraordinary innovation in the Republic's rituals.

Much more importantly, Giscard went on to adopt a number of major social reforms in under a year. These included reducing the age of majority and voting to 18; free provision of the contraceptive pill under the healthcare system; the so-called loi Veil law that legalised abortion in 1975; divorce by mutual consent; the first junior ministry for women's issues; and the end of the Office de Radiodiffusion-Télévision Française (ORTF) which oversaw the nation's television and radio stations under strict government control.

Some important political reforms quickly followed. There was an elected mayor of Paris instead of an official nominated by the state; a strengthening of constitutional oversight, with senators or Members of Parliament given the right to refer matters to the nation's Constitutional Council if 60 or more of them agreed; and working immigrants were allowed to bring their families over.

Society, therefore, was the main beneficiary of the start of Giscard's seven-year presidency. Of course these reforms were wrestled from a government faced with large demonstrations, but they did take place. Giscard was trying to bridge the gulf that then divided political power and French society.

Emmanuel Macron made exactly the opposite choice. His first year in office was marked by a raft of decrees which progressively installed ultra-liberal economic reforms. He got rid of the wealth tax; brought in a flat-rate tax and reductions in corporation tax and tax on capital; and dismantled employment law. Then came a reform of unemployment benefit (which was so brutal that it is currently suspended) and then pension reforms that brought large sections of the country out onto the street for months in protest.

Where are his promised social and political reforms? They have either been postponed or abandoned because they were badly negotiated (the only exception being the opening up of fertility treatment to all women). Society has not been listened to. Instead it has been rebuked and lectured, and told it has to adapt to triumphant neo-liberal globalisation.

We have been treated to a series of comments from Emmanuel Macron on this theme since May 2016, even before his election as president. “The best way of paying for a suit is to work,” he told members of the CGT trade union. In June 2018 he referred to the “crazy money” that state benefits cost. Two months later President Macron described the French as “Gauls who are resistant to change”. Then, a few weeks later, he told someone looking for a job: “If I crossed the street I'd find you one.”

The same switch to repression and law and order

The result was social unrest, with the gilets jaunes or 'yellow vest' movement that at one point threatened to bring down the government. Emmanuel Macron complained ironically about the media coverage accorded to the protest movement, claiming that “Jojo the Yellow Vest has the same status as a minister” - 'Jojo' is a familiar term for a rascal or joker. But 'Jojo' derailed his presidency. The government lost its grip, control of the agenda and its ability to reform – as was seen with the enormous social conflict over its pension reforms. The health crisis completed the job.

Go back nearly fifty years and Giscard, too, hit a brick wall after less than two years in office, one which effectively brought an end to his presidency. This was not the decision of Jacques Chirac to quit as prime minister in 1976 but rather an economic crisis which grew and became a permanent fixture. It was the result of the oil crisis and above all of the exhaustion of the old model of economic growth employed in France during the post-war period known as the Trente Glorieuses. The “best economist in France”, Raymond Barre, was then made prime minister to inflict the first austerity measures on the country.

So at this point the paths of the two men, Giscard and Macron, start to converge again. Both opted for the same response, a conservative approach that was based on law and order and security. Giscard's political camp was not just full of reformers. It had also always included the old traditional right that had been associated with the days of the war-time Vichy government in France without being tainted by it. Giscard's circle also included intellectuals and activists from the far right, from groups such as Ordre nouveau, Le Club de l’horloge and Occident – for example Gérard Longuet, Alain Madelin and Anne Méaux.

Giscard closeted himself in his Elysian palace, a solitary monarch who was now rocked by scandal after scandal; the diamonds of Emperor Bokassa, the murder of politician Jean de Broglie, the murder of government minister Robert Boulin, the great oil sniffer hoax of 1979 … No longer could Giscard simply play the accordion, or go and dine among the French people and listen to society.

Enlargement : Illustration 2

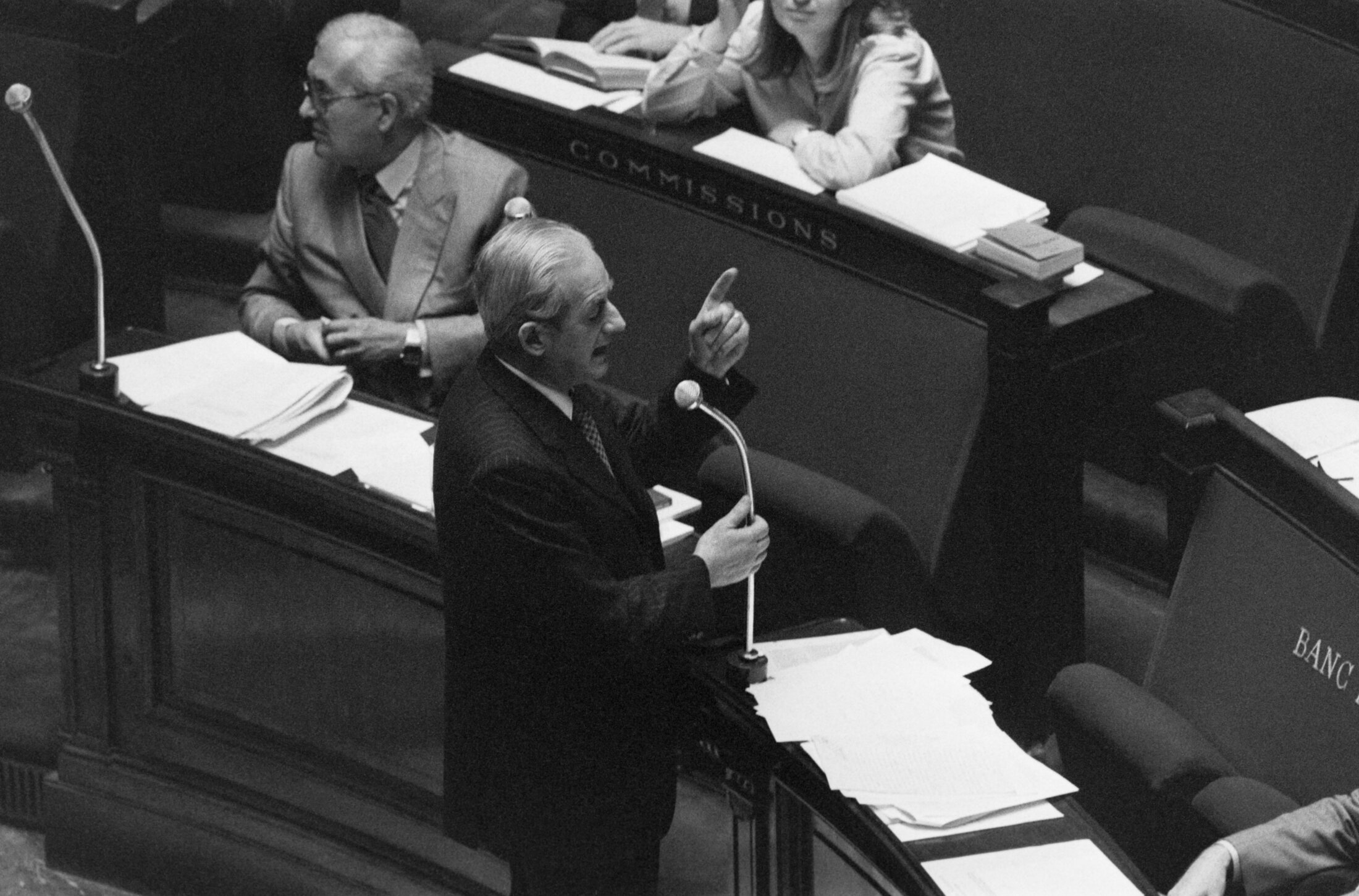

Three men, all loyal supporters of Giscard, brought about the switch towards reactionary and repressive policies during his presidency. These were Michel Poniatowski, Christian Bonnet - who replaced him in 1977 as minister of the interior - and Alain Peyrefitte, minister of justice (1977-1981). What followed was an increase in the suppression of social and environmental protests. One law above all came to symbolise this law and order clampdown. This was a law on security and freedom proposed by Peyrefitte (see photo above) and which became law in February 1981, before being effectively abolished after socialist François Mitterrand became president later that year.

In an article in Le Monde on April 28th 1979, the journalist Philippe Boucher analysed the law and order measures that Giscard had called for. “A great number of [legal] texts, and an even greater number of speeches, concerned freedoms! But what they all had in common was to restrict them, not to protect them,” he wrote. They also set out the “perils” of the freedom of publication, of expression, protest and association, and well as of criminal defence rights. There was also an “undeniably xenophobic” law being prepared in relation to foreign citizens.

This law on freedom and security was the culmination of years of gradual slide towards repression seen under Giscard's government. As noted in a recent article by Jérôme Hourdeaux on Mediapart, during the Parliamentary debates on this law “the Members of Parliament from the ruling party at the time described a France that was torn apart which was not really any better than the 'en-savagement' depicted by their colleagues in 2020.”

Giscard leaned on Alain Peyrefitte, who supported him when he stood again as a candidate in 1981. Macron is relying on his new interior minister Gérald Darmanin to carry out the switch towards more identity-based, repressive and law and order policies that has taken place since the summer when there was a change of prime minister and government. Paralysed by the health crisis and by social protests, and with no track record at all on social issues, Emmanuel Macron is trying to impose a very different agenda based around attitudes towards Islam, fear of terrorists, rampant xenophobia and attacks on freedoms.

As he himself wrote, Valéry Giscard d’Estaing was sure he would be re-elected in 1981. He had destroyed any competition on the right. He did not understand, however, that the way he governed, his economic policies and the way he ran the ministries of the interior and justice fuelled the desire for a change. And he was beaten.

“His story came across as an individual adventure, when it should have come across as a collective one,” says François Bayrou today. He was speaking about Valéry Giscard d’Estaing. One can be forgiven for believing that he was thinking very much of Emmanuel Macron as he said it.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The original French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter