It was supposed to be the event at which Emmanuel Macron rang the starting bell for his presidential campaign. On Saturday February 4th the former employment minister and independent candidate held a rally on friendly territory in the eastern city of Lyon, where his friend and supporter Gérard Collomb is socialist mayor and senator.

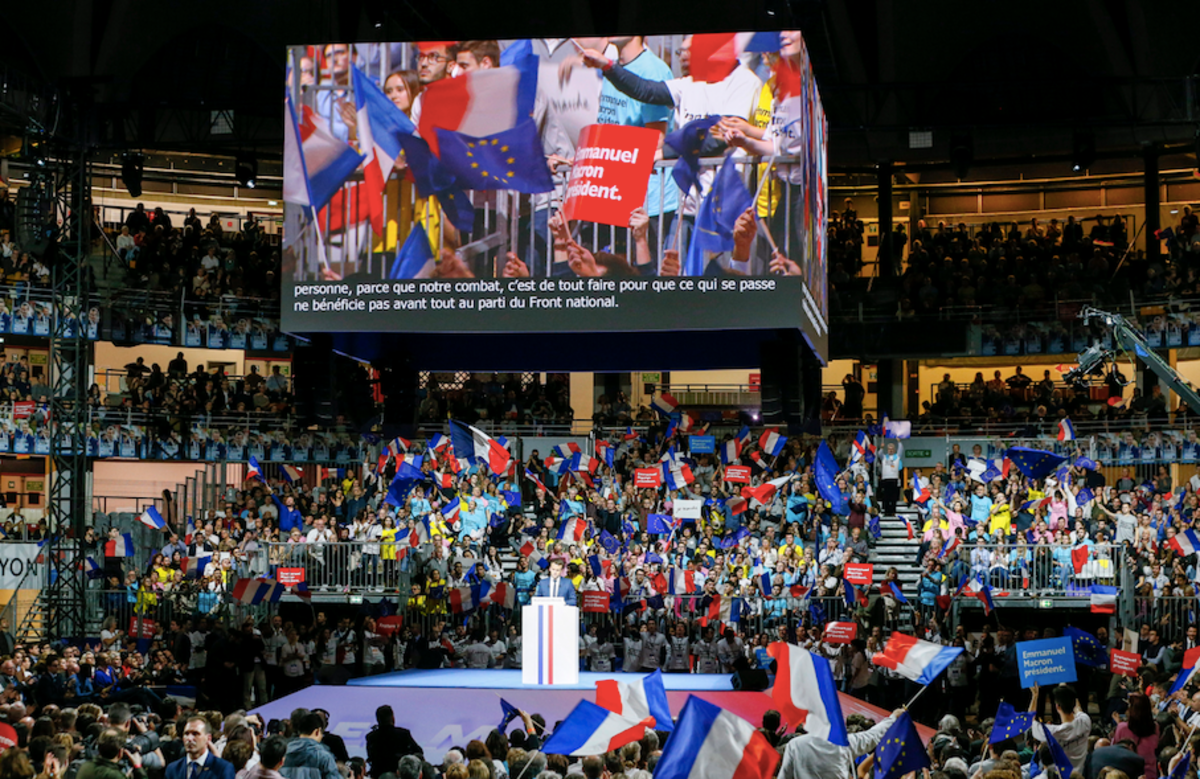

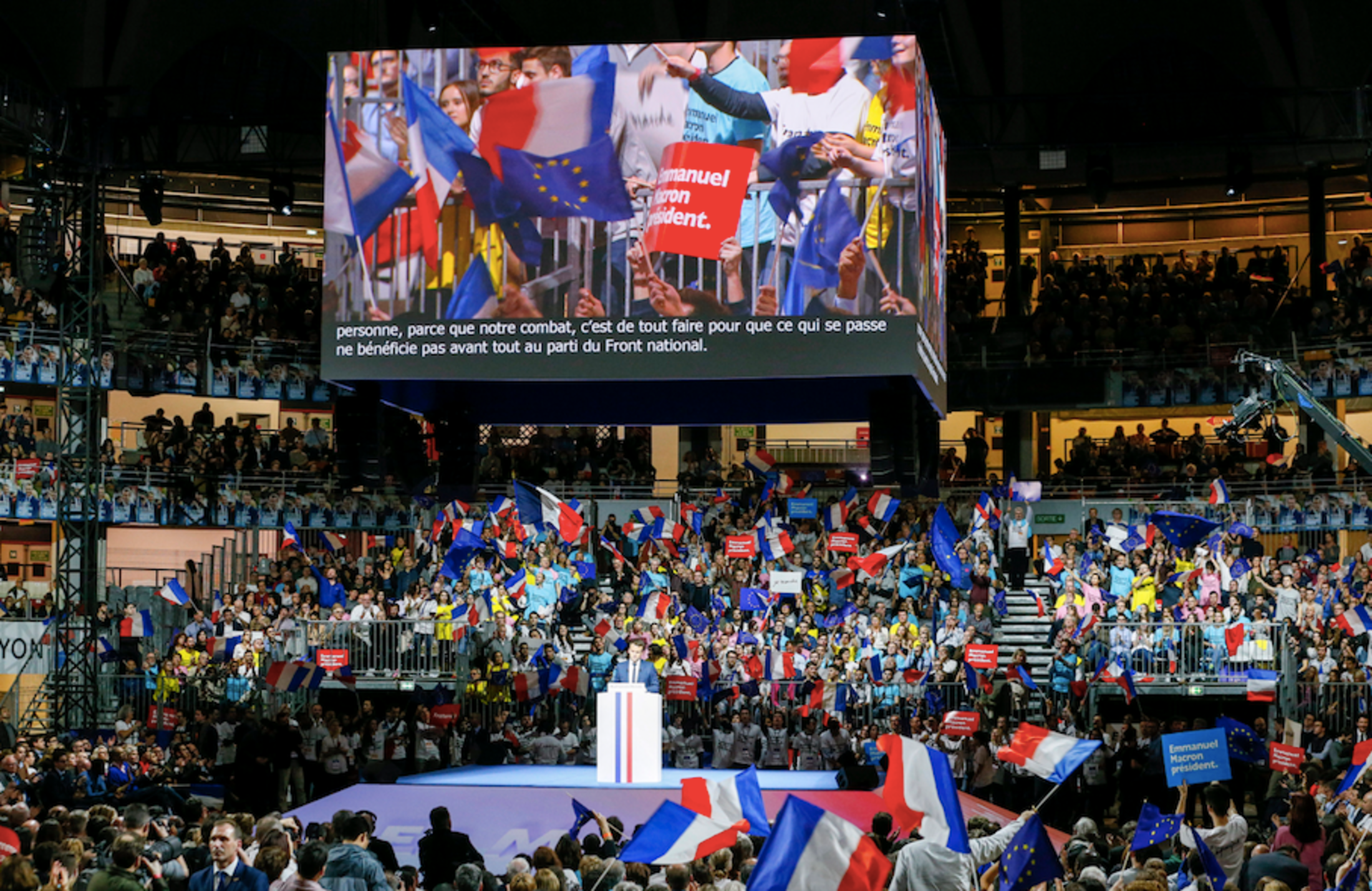

All was set for lift-off at the Palais des Sports, filled with the now obligatory large crowd of Macron fans; some 6,500 inside the arena with thousands more watching the event outside on giant screens. Some supporters wore pink, light blue or yellow t-shirts while new posters emblazoned with the words “Macron President” had been made. The stage itself was all screens and flashing lights, giving the occasion the appearance of an American political convention.

Yet when it came to Macron's speech, it proved to be something of a false start. It was as if the candidate, still uncertain about who all his opponents will be – notably whether his right-wing opponent François Fillon will survive his 'fake work' controversy – had decided to play for time before plunging headlong into battle. Yet for Macron the coming weeks are crucial ones. Over and above the success of his rallies and his rise in the polls, he needs to establish the “central” political space that he intends to represent. And, in the words of a friend, he needs to prove that this man of 39, who three years ago was a complete unknown, is someone to whom the French people can “give the keys of the lorry”.

In a speech peppered with formulaic, sometimes clichéd comments, and read in the tone of a dozing TV evangelist, Macron the candidate of “Left and Right”, went out of his way to emphasise togetherness. He appears to believe that it has fallen to him to oversee one of those historic moments when the French nation is able to reconcile itself. For example, as in 1905 and the key law on church and state segregation; and the notorious Dreyfus affair when “the talents of Émile Zola and Charles Péguy were required”. He talked, too, of wartime Free France when “communists, Christians, Freemasons and conservatives” came together because “they had the same project, France”. And of what is known as the 'loi Veil', the legislation legalising abortion in France in 1975 when “it needed a majority from the Right and the Left to be able to vote it through”.

“We see ourselves as following on from these great moments of coming together,” he said. Macron regards himself as someone who can unite “social democracy, realistic environmentalism, radicals on the Left and Right, social Gaullism [editor's note, a reference to the policies of Charles de Gaulle], the Orleanist Right [editor's note, as exemplified by the French president of the 1970s Valéry Giscard d’Estaing], the European centre-right”. He justifies the need for unity by the seriousness of the current situation. “We are living at a particular moment in our history,” he said. “One of those rare moments where destiny hesitates, where what seemed certain no longer is, where the straight line of yesterday can change direction.”

Macron's view seems to be that we have to be able to overcome political differences. “I'm not telling you that Left and Right no longer mean anything … but at historic moments are these differences insurmountable? Did one have to be from the Left to be moved by the great speeches made by François Mitterrand a few weeks before his death? Did one have to be from the Right to feel pride during the speech by [President Jacques] Chirac on the Vel' d'Hiv [a 1995 speech in which Chirac accepted France's role in the deportation of Jews in World War II]? No, one had to be French,” Macron told his supporters.

Enlargement : Illustration 1

Barely ten weeks before the first round of the presidential election, Emmanuel Macron is hesitating about showing all his cards because he still does not know which political space he is going to be able to poach between now and voting day. Benoît Hamon was formally anointed as the Socialist Party candidate on Sunday February 5th and if over the coming weeks his campaign takes off without breaking up the Socialist Party itself – something Macron has gambled on – then the latter will be forced to seek more votes from the political centre ground.

Meanwhile if the beleaguered right-wing candidate François Fillon remains in the race despite the 'fake job' controversy – and he shows ever sign of seeking to cling on - then Macron could expect to attract some disenchanted voters from the Right. If, however, Fillon is forced out of the contest quickly then the room for manoeuvre that Macron has will depend on whether the Right chooses a hardliner or a moderate as a replacement. The last unknown factor is whether the centrist politician François Bayrou decides to stand or not; a decision is due by February 15th. Bayrou and Macron would offer similar centrist messages, seeking to appeal “above the parties”. In recent days it is clear that Macron has made overtures towards Bayrou.

So while he keeps an eye out until the political landscape becomes a little clearer, the former economy minister under President François Hollande used his speech in Lyon to shore up his current position. Macron, who styles himself as the candidate for jobs, criticised plans for a universal income by Hamon. Macron said this pledge would mean that people would be able to “live with dignity in an endured or voluntary idleness”. Macron added: “I have seen women and men … who have lost their jobs, who've known unemployment and now the minimum social benefits. They didn't ask me for a a universal income, they have it – it's called the RSA.” This was a reference to the French work welfare benefit known as the Revenu de Solidarité Active.

Macron, who sees himself as a defender of “freedom of conscience” rejects the idea of banning women from “working in a veil”. But his reference to a television report - which showed how in suburbs of Paris and Lyon women were effectively barred from some cafés – contained an implicit attack on Hamon, whose comments on the subject have been described as ambivalent. Without citing Hamon's remarks, Macron said: “This freedom of conscience is about respect for our civility. … I don't accept that men's glances can ban a woman from coming and sitting at a terrace or in a café.”

The former minister and merchant banker criticised the behaviour of Fillon in the 'fake job' saga as “practices from another age”. But he immediately then attacked the far-right Front National (FN), which was holding its own gathering in Lyon on the same weekend. “Our fight is to do everything to make sure that what happens does not benefit the Front National … whose practices are every bit the same as those they criticise.”

Macron continued: “Some claim that they speak in the name of the people [editor's note, the FN's slogan] but they're just ventriloquists. They ascribe to the French people values that are not theirs … they speak in the name of their bitterness. They don't speak for the people, they speak for themselves, from father, to daughter, to niece [editor's note a reference to party founder Jean-Marie Le Pen, his daughter Marine Le Pen, the current FN president and her niece MP Marion Maréchal-Le Pen]. They don't speak for the people but of a France that never existed.”

'Freedom is first and foremost about security'

It was a catch-all speech by Macron which said much about the improbable patchwork of ideas that make up his imaginary world. For example, he welcomed Germany's policy of welcoming migrants and held himself up as a guardian of world freedoms when he made a “solemn appeal to all scientists, all academics, all the companies who, in the United States, are fighting against obscurantism” to come to France after his election. But he also proclaimed that “freedom is first and foremost about security”, a hackneyed formula that the far right helped popularise in the 1980s.

He referred to Zola and François Mitterrand, icons of the Left, but also nodded towards the centre-right and Right, citing Simone Veil, the minister who brought in the 1975 abortion law, Jacques Chirac, Charles De Gaulle (whom he referred to as “The General”) and the former president of the National Assembly Philippe Seguin, who did not share any of Macron's pro-European convictions. Before the meeting began he greeted the former boss of the Miss France competition in France, Geneviève de Fontenay, who last year took part in a demonstration by 'Manif Pour Tous', who are opposed to the legislation on single-sex marriage. Macron's visit last summer to see hard-right politician Philippe de Villiers, who is behind the successful Puy du Fou theme park in western France, led to criticism from inside the candidate's own En Marche! movement.

Macron is still continuing to be evasive on fundamental issues. Though he has already set out some policy proposals, his manifesto – with costings – is only expected at the end of February. So in Lyon Macron simply read out his chapter headings without announcing anything new. His friends insist that there is no rush. The presidential election is first and foremost about an “encounter between a man and a people”, they say. Macron, who has adapted to the institutions of France's Fifth Republic, sees himself in this very traditional role.

So rather than just providing a catalogue of proposals, he is banking on himself as an individual, his youth, his “freshness”, his positive speeches and on voter fatigue with the old parties. Dragging out the presentation of his manifesto also has another advantage. Emmanuel Macron wants to avoid the boomerang effect of the measures, some of them very liberal economically, that he has already put forward. For example there is the policy of employment law practices being agreed at company level with workers, the obligation for a jobless person to accept a job after training and cuts in state administration spending. He doubtless believes that the words of the 17th century French churchman Cardinal de Retz that “one leaves ambiguity only at one's own expense” are the basis of a good strategy. Yet as time goes by the pressure on Macron to set out his manifesto increases as his opponents decry his political zigzagging.

His possible centrist rival François Bayrou has described Macron as a “hologram” and continues to say that he has “no direction, no manifesto and no vision”. His Socialist Party opponent Benoît Hamon has likened him to a car indicator. “One day it's the Orleanist Right, another it's the progressive Left. You need to catch him on the right day.”

Macron's predecessor as economy minister, Arnaud Montebourg, who was defeated in the Socialist Party primary that Hamon won, has attacked Macron as “Mr X” or a person unknown, who “can go to Philippe de Villiers' place Puy du Fou to pay tribute to him, then take the train to Nevers [in eastern France] to praise François Mitterrand, then get back on the train to head for Chanonat, Valéry Giscard d'Estaing's home town, to praise Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, receiving between journeys and stops the support of [former centre-right prime minister] Jean-Pierre Raffarin and the criticism of [Senate president] Gérard Larcher.”

The socialist mayor of Paris Anne Hidalgo, meanwhile, has made ironic reference to Macron and his “imposed face of modernity”. The former socialist justice minister Christiane Taubira says she is “dismayed” by his “impact on young minds”. She says: “When you've been committed for more than 30 years, when you've taken politics seriously, when you've accepted the blows … you know the difference between Left and Right. Generations have paid with their flesh for demanding a world that is fairer and more equal.”

The head of Socialist Party MPs at the National Assembly, Olivier Faure, says of Macron: “I know where he comes from but I don't know where he is going.” So far Faure has succeeded in stopping the Parliamentary party from haemorrhaging support towards Macron. “I can find myself in agreement with him on certain projects but what distinguishes us is the overview,” says Faure. “He is a real liberal in the 19th century sense. To say 'may the best win', to speak even of equality of opportunities, to push some to become billionaires in the hope this will stimulate others, that's not a social plan. His speech might be seductive but my vision is one of reform and continued social and democratic progress, not becoming a version of the American Democratic Party.”

Macron replies to such critics that they are precisely the representatives of a “system” that he, who attended the elite ENA institution in France, and was a member of a prestigious corps of public servants, a merchant banker and then a government minister, intends to battle against. “There are some people who don't want to get used to reality but who tell you that you are virtual,” he said on January 14th in Lille in northern France. “For some it's a strategy, for the rest it's persistence of vision. It will pass and it doesn't matter.”

In reality, Emmanuel Macron is going to have to provide answers on many points between now and the presidential election. Answers about his manifesto, of course, but also about the people with whom he intends to govern. Who would be his ministers, what room for manoeuvre would a President Macron give to Parliament, what would the balance of power be? Unless, that is, Macron follows the strategy of hypnotists who are accustomed to putting people's minds at rest by suggesting to their unconscious mind that the questions gnawing away at them do not really exist.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

- The French version of this article can be found here.

English version by Michael Streeter